Interpretive Difficulty

On June 21, 2021, I added a postscript to this essay.

— Joshua Kotin

I

On April Fool's Day, 1965, Amiri Baraka (known then as LeRoi Jones) sent a postcard to the poet Kenneth Koch. The image on the front of the postcard is racist: three alligators chase a Black man, who looks up to heaven with tears streaming down his face. A four-line poem presents his "prayer":

Dese gater looked so feary

And yet dey 'peered so tame

But now that I done met 'em

I'll neber be de same.1

According to the Newberry Library, the Curt Teich Company began producing postcards with this image in 1940. But Teich produced similar postcards as early as 1918, and the "alligator bait" stereotype has a much longer history.2

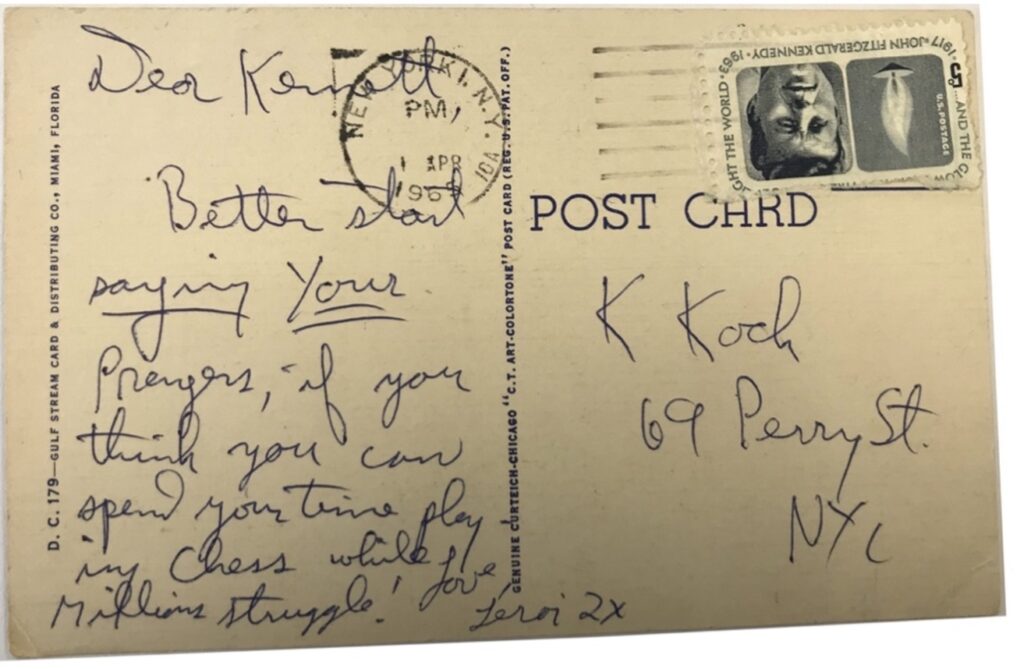

On the back of the postcard, Baraka writes:

Dear Kenneth,

Better start saying your prayers, if you think you can spend your time playing chess while millions struggle!

Love,

LeRoi 2X3

The postcard was sent to Koch's apartment at 69 Perry Street in New York's West Village, using a five cents John Kennedy stamp. The postmark indicates that the postcard was processed in the afternoon on April 1.4 Koch likely received it the next day. I don't know where Baraka purchased the postcard, or whether such postcards were easily available in New York in the mid-1960s. Today, they are collectors' items.5

What kind of April Fool's Day joke was this? Was the postcard even a joke? Or was it a threat? The case for reading the postcard as a joke is precarious, yet plausible. We have the date. We know that Baraka and Koch were friends. In The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones (1984, 1997), Baraka describes hanging out with Koch and other New York School poets at the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village: "the New York school people, Frank [O'Hara], Kenneth, would be holding court along with any number of painters (Larry Rivers, Mike Goldberg, and Norman Bluhm were special friends of Frank's)."6 Perhaps the postcard extended a private joke — about the absurdity of Jim Crow or the earnestness of Black nationalism, or both.

We also know that Baraka admired Koch's poetry and sense of humor. In Autobiography, he praises Koch's "Fresh Air" (1956) for "single-handedly demolish[ing] the academic poets (even if they couldn't dig it)."7 The poem depicts a strangler-vigilante killing "several bad poets":

The yellow hobbyhorse rocks to and fro, and from the chimney

Drops the Strangler! The white and pink roses are slightly agitated by the struggle,

But afterwards beside the dead "poet" they cuddle up comfortingly against their vase. They are safer now, no one will compare them to the sea.8

Perhaps the postcard picked up the poem's mock violence to mock Koch's own imbrication in academia. (That spring, he was preparing to apply for promotion to associate professor at Columbia University.) The poet Lorenzo Thomas connects "Fresh Air" to Baraka's ultraviolent "Black Art" (1965), arguing that the two poems "articulate [ . . . ] a similar aesthetic polemic."9

There is yet another reason to read the postcard as a joke: Koch loved postcards, especially bizarre ones. In 1964, he published the story "The Postcard Collection" in the first issue of Art and Literature. The story's narrator, an unnamed postcard collector, speculates about the meaning of a series of old French postcards:

[T]he last hypothesis — that the card was written from deep wells of sunlight and contentment — seems contradicted by the scene that is pictured on the card. That scene is, as we have already noticed, naive and even simpleminded. Then was the card sent to amuse the recipient? The possibility is rendered unlikely by the first and almost completely legible sentence on the back (see above).10

The critic Laura Steele associates the story with Jorge Luis Borges's Ficciones (1944, 1962), Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire (1962), and Jacques Derrida's The Post Card (1980, 1987).11 A small act of interpretation unfurls into a wild and contradictory meditation on art, skepticism, and the meaning of life. Baraka likely read the story in Art and Literature, or about the story in Ted Berrigan's review of Art and Literature in the journal Kulchur, which Baraka co-edited.12

But the most compelling reason to read the postcard as a joke isn't the date or Baraka's connections to Koch or Koch's love of postcards. The most compelling reason is the postcard's outrageousness. The détournement of the image. The melodramatic underlining — and double underlining. The upside-down Kennedy stamp, which, once cancelled, resembles an upside-down flag. (Does the flag signal irreverence or "distress"? Both? Neither?)13 The complimentary close and signature must be a joke, right? LeRoi and two kisses? Or more likely: Baraka is parodying Nation of Islam naming practices. (He did not actually change his name until 1968.)14 Surely there were more than two members of Mosque No. 7 named LeRoi. In the epilogue to The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), Alex Haley mentions a James 67X — "the 67th man named 'James' who had joined Harlem's Mosque Number 7."15

Yet the case for reading the postcard as a threat is more persuasive. In February 1965, Baraka was living with his White wife, Hettie Jones, and their two children in the East Village. (His apartment at 27 Cooper Square was one mile from Koch's.) The assassination of Malcolm X on February 21 led to a radical break. "I was stunned, shot myself," Baraka writes in Autobiography; "I felt stupid, ugly, useless. Downtown in my mix-matched family and my maximum leader/teacher shot dead while we bullshitted and pretended."16 In early March, he left his family and moved to Harlem. "My little girl, the older one, Kellie, picked up instinctively a sense of my departure. [ . . . ] But in a minute or so, I was gone. A bunch of us, really, had gone, up to Harlem. Seeking revolution!"17 Would Baraka have sent Koch an April Fool's Day joke in this context?

Baraka's public persona that winter and spring supports reading the postcard as a threat. Vivian Gornick describes a forum on art and politics at the Village Vanguard on February 8, featuring two Black artists, Baraka and Archie Shepp, and two White artists, Larry Rivers and Jonas Mekas. During the question-and-answer period, a White woman asked what she could do to help race relations. "Die baby," Baraka responded; "The only thing you can do for me is die."18 (In Autobiography, Baraka recalls responding, "You can help by dying. You are a cancer. You can help the world's people with your death.")19 Reflecting on that time in his life, he writes: "I got the reputation of being a snarling, white-hating madman. There was some truth to it, because I was struggling to be born, to break out from the shell I could instinctively sense surrounded my own dash for freedom."20 The postcard could be read in the context of this struggle.

The reference to chess reinforces reading the postcard as a threat. (The game is a readymade symbol of race relations.) In both Autobiography and the autobiographical novella, 6 Persons (1973-1974, 2000), Baraka describes a confrontation with "Big Brown," an African American "proto Arnold Schwarzenegger," who would stand around "Washington Square Village profiling."21 One night at a coffeehouse downtown, Baraka mocked Brown for losing a chess match. In response, Brown threatened Baraka. When Baraka refused to apologize, Brown relented. "In the real world," Baraka writes, "all that mouth would've got me killed. [ . . . ] But down there, wow, even the bad dudes was cardboard Lothars afraid of their own shadow."22 Koch likely knew the story, and would have recognized the association of chess and duplicity.

The association of chess and duplicity embeds the image on the front of the postcard in complex narrative of victimization and vengeance. In this narrative, Baraka initially identifies with the Black man, who misunderstands the danger posed by the alligators — presumably Koch and the White world downtown. Baraka then flips the script, trading positions with Koch, who now misunderstands the danger posed by Baraka. (Koch is forced to voice the postcard's poem or "prayer.") Baraka, in this way, transforms the postcard's racist kitsch into anti-racist fable.

Ultimately, the best reason for reading the postcard as a threat is that it couldn't possibly be a joke. As a joke, the postcard would undermine Baraka's politics — his life. Yet the best reason for reading the postcard as a joke is that it couldn't possibly be a threat. From one perspective, the postcard embraces — and perpetuates — the irony associated with the New York School. From another, the postcard obliterates it.

The postcard is difficult to interpret. And the stakes are high. Not only the meaning of a specific text, but the relationship between two people, and the import of Baraka's work. If the postcard is a joke, how should we read his poems and plays from the period? If the postcard is a threat, same question.

The situation is further complicated by the postcard's uncertain provenance. I found the postcard in the LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) Collection at the Special Collections Research Center at Syracuse University.23 Syracuse would only tell me that the postcard was acquired in 2013 from a "manuscripts and books dealer."24 I managed to discover, however, that Jeff Maser and James Musser bought the postcard from Glenn Horowitz and then sold it to Syracuse for $250. But that's where my knowledge of the postcard's provenance ends. I don't know why the postcard isn't part of the Koch papers in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library. Did Koch withhold the postcard from his papers, or sell it or give it away? Was it simply misplaced?

II

Couldn't the postcard be both joke and threat? But couldn't we read Baraka's relationship to Koch as an extreme example of an everyday contradiction: the frenemy?

The "incredibly useful word," Jessica Mitford writes in "The Best of Frenemies" (1977), was "coined by one of my sisters when she was a small child to describe a rather dull little girl who lived near us. My sister and the Frenemy played together constantly [ . . . ] all the time disliking each other heartily."25 The Oxford English Dictionary, however, traces the word to 1953. At the height of the Cold War, the journalist Walter Winchell asked, "Howz about calling the Russians our Frienemies?"26

The word makes sense of Baraka's relationship with Larry Rivers, one of the two White speakers at the forum at the Village Vanguard on February 8, 1965. The poet Bill Berkson describes meeting Baraka and Rivers at a party at Frank O'Hara's loft just before the forum:

I remember standing with the two of them beside Frank's fireplace, the three of us talking about baseball or some such thing and then each of them making light of the discussion for which they were then obligated to leave the party. The next morning the Times had the story: "LeRoi Jones Attacks Larry Rivers."27

According to the New York Times, Baraka called the forum's mostly White audience, "'our enemies.'" Rivers then "inquired about his own standing and got the cheerful reply [ . . . ] that he was like the others — 'except for the cover story.'"28

At the same forum, Shepp used a less cute alternative to "frenemy" to describe his own relationship with Rivers. Harold Cruse describes the exchange in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967):

But Shepp said, relentingly, to Larry Rivers, "I consider you a friend, an enemy." There was laughter from the audience, but Shepp insisted: "I spoke the truth. I mean both things."29

One can imagine Baraka using these exact words to describe his relationship with Koch: "a friend, an enemy" — "I mean both things."

Such ambivalence is an understandable response to structural racism. Baraka may have loved Koch as a person and poet, but hated what he represented — White supremacy, the White world downtown. When read as both joke and threat, the postcard captures this combination of love and hate.

Is the postcard's ambivalence more like the ambivalence of a poem or a person? (Ambivalence, Adam Phillips reminds us, does not "mean mixed feelings, it means opposite feelings.")30 Is there even a significant and generalizable difference between the ambivalence of a poem and a person? Can the postcard help identify it?

Poems and people are often — and perhaps always — ambivalent. Ben Lerner makes the case for poetry's intrinsic ambivalence in The Hatred of Poetry (2016).31 Sigmund Freud makes the case for our own. "In Freud's vision," Phillips writes, "we are, above all, ambivalent animals: wherever we hate we love, wherever we love we hate."32

But poems and people are also ambivalent in specific ways. For Helen Vendler, ambivalence is an achievement of poetic form.33 In a reading of W.B. Yeats's "Easter 1916" (1916), she asks:

Even if Yeats wanted to praise the rebels' bravery, their love of Ireland, and their faith in proclaiming a Republic that did not yet exist, how could he praise them, since he had refused to condone their turn to armed violence? How could he write a poem reflecting on their actions that would not be propaganda for their attitudes?34

"Easter 1916" is the answer — a poem "so ambivalent," Vendler writes, that it "allows us to see several states of [Yeats's] mind."35

For Freud, in contrast, ambivalence is a risk to mental health. In "Notes upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis" (1909), he argues that the "true significance" of the Rat Man's compulsive acts "lies in their being a representation of a conflict between two opposing impulses of approximately equal strength: [ . . . ] love and hate."36 Freud treats the Rat Man by helping him trace the history of his ambivalence.

Is the postcard more like "Easter 1916" or the Rat Man? Or less facetiously: is the postcard's ambivalence an achievement or a problem? I'm tempted to answer "both" — but I think the answer is actually "neither." (Unfortunately, "neither" creates more interpretive difficulties than "both.") If pushed, I might retreat and simply admit that I don't know. Can interpreting the postcard, then, teach us anything about interpreting poems or people, or interpretive difficulty as such?

When I began thinking about my contribution to this cluster, I hypothesized that selecting a postcard might be an easy way to elucidate interpretive difficulty. Postcards promised to be less complicated than poems or people. Unlike poems, postcards do not attempt to transcend history; they relay specific messages to specific people in specific contexts. Unlike people, postcards do not change. I had hoped, moreover, that selecting a postcard might allow me to evade the extensive, overwhelming discourse about interpreting poems and people.

But postcards present their own challenges. They are, at once, private and public: sent to specific people, yet exposed to the world.37 (Sending a postcard may have been the best way for Baraka to express his love for a friend in private and perform his hatred of White supremacy in public.) Postcards are also collaborative, juxtaposing mass-produced images with unique messages. Postcards may be less complicated than poems and people — but they are still complicated. (Koch's "The Postcard Collection" and Derrida's The Post Card should have been a warning.) If Baraka's postcard were a poem, I could point to its ambivalence as an end in itself, or connect its ambivalence to an abstract debate about friendship and structural racism. If the postcard were a person — or a direct statement from one person to another — I might have been able to evaluate Koch's reaction or Baraka's tone.

The weakness of my initial thinking does not end there. Does it even make sense to compare "Easter 1916" and the Rat Man? Wouldn't it be better to compare "Easter 1916" and the Rat Man's sessions with Freud, and Yeats with the Rat Man? These questions lead to others. Is ambivalence a good way to understand interpretive difficulty — or the difference between poems and people?38 Does ambivalence capture the complexity of human attitudes and relationships?

This conclusion is not satisfying: an abstract interpretation of the postcard — "a friend, an enemy" — and a metastasized understanding of interpretive difficulty. One way to escape this conclusion might be to ask a different kind of question. Instead of asking what the postcard means or what it is — ask what it does. Pragmatism is a refuge in the face of interpretive difficulty. The postcard likely did what it needed to do: put Baraka's relationship with Koch on hold. As far as I can tell, Koch did not respond with a humorous postcard of his own. He certainly didn't call the police. He simply stayed away.39 "LeRoi seems not to be interested in us-all any more," O'Hara wrote John Ashbery on April 26, 1965.40 The postcard, one might argue, instantiated that lack of interest. A friend, an enemy — both and, ultimately, neither.

A Postscript

At 10:29 a.m. on Wednesday, May 26, I received an email from Johanna Winant, the cluster's editor: "If you haven't seen it already, our Post45 cluster, Interpretive Difficulty, just went live."41 At 11:35 a.m., I received an email from the scholar Nick Sturm, suggesting that the premise of my contribution was incorrect: Baraka had not, in fact, written the postcard.

"The postcard is written entirely by Ted Berrigan," Sturm wrote; "It's 100% Berrigan's handwriting."42 Sturm supplied examples. He also argued that the postcard fit a pattern:

Berrigan was keen on April Fool's jokes, especially in the 1960s when he could humorously play up and off antagonisms in NYC literary communities. Miming the voices of others in wry ways was a hallmark of Berrigan's dada-esque embrace of the poet as pop criminal.43

Sturm signed off: "I love that Ted's April Fool's joke held up so well!"44

Was Sturm correct? Had Berrigan written the postcard? When I began to work on this essay, I had compared Baraka's handwriting to the handwriting on the postcard. They seemed to match. But Berrigan's handwriting seemed a better match. Regardless: Sturm's suggestion promised to resolve many of the interpretive difficulties that had motivated my essay in the first place.

In my original essay, I had asked: "What kind of April Fool's Day joke was this? Was the postcard even a joke? Or was it a threat?" If Berrigan had written the postcard, the answers to these questions would be comparatively straightforward: yes, a joke — a racist joke. Berrigan, a White poet, would be responsible for sending a racist image, and for mocking Baraka's radicalization — in blackface no less. A joke — and no joke at all.

Who was Ted Berrigan? In 1965, he was establishing himself as an important figure in the downtown poetry world. He had published his first book, The Sonnets, a year earlier, and was currently editing "C" Press and "C" Magazine (1963-1967), which included contributions from both Baraka and Koch. (Baraka contributed to one issue; Koch to five, including four consecutive issues between 1964 and 1965.) The Sonnets is at once a major poetry collection and a tribute to Berrigan's poetry heroes: O'Hara, Ashbery, and Koch, all of whom it quotes extensively. According to the poet and critic Jordan Davis, the book is a "courtly exercise in personal canon formation"; Berrigan "taught himself how to write by stealing other poets' lines."45

One can imagine Berrigan using the postcard to consolidate his friendship with Koch. He was alert to Koch's love of postcards. He had, after all, just reviewed Koch's "The Postcard Collection" for Kulchur. He was also alert to the controversies surrounding Baraka's radicalization — he may have even attended the forum at the Village Vanguard. The April Fool's Day joke may have seemed a perfect way to connect to one of his influences and build a community. Would Koch have been fooled? I doubt it. But one can imagine that he experienced a brief interval — a split second — of bewilderment bordering on fear as he tried to make sense of the postcard.

This hypothetical narrative exposes the very context Baraka was attempting to escape when he moved to Harlem in March 1965. Not just White supremacy, but a particular brand of New York School White supremacy. Instead of exemplifying the complexity of Baraka's radicalization, the postcard exemplifies the ease with which that radicalization could be used to reinforce White solidarity.

But not so fast: Sturm's re-attribution might not be correct. On May 31, he wrote me again. He'd been in contact with the poet Alice Notley, Berrigan's widow, and recommended that I write her myself. I did and she replied immediately:

I don't think Ted wrote this postcard. It just doesn't feel like something he would do, particularly in 1965 when he was still a young man who worshipped Kenneth, and Frank and John. Also it isn't funny enough. I think your essay is probably correct.46

Notley also did not think the handwriting matched Berrigan's — "his handwriting tends to be more deliberate than that in this postcard."47 She also speculated that someone else might have written the postcard: "there was a guy who shot Kenneth with a water pistol at a reading once, I think it was Allen Van Newkirk."48

A problem of interpretation had become a problem of attribution. If Baraka had written the postcard — interpretive difficulty. If Berrigan had written the postcard — that difficulty dissolves. If someone else had written the postcard — who knows?

"Interpretation and attribution have much to do with each other," my colleague Jeff Dolven explained in an email after I outlined the impasse; "but you can also use each to cancel or avoid the other."49

What if we were to refuse to let the problem of attribution cancel or avoid the problem of interpretation, and vice versa? What if we tried to keep both problems live? One way might be to ask: why didn't I consider the problem of attribution more fully as I was interpreting the postcard?

In hindsight, I should have been more skeptical of previous attributions. Jeff Maser and James Musser were, I think, the first to identify Baraka as the author of the postcard. (Horowitz had offered the booksellers a small collection of postcards sent to Koch.) Maser generously shared their original description:

[AFRICAN-AMERICAN] JONES, Leroi. Autograph Postcard Signed to writer Kenneth Koch. New York City, 1965. Racially offensive postcard depicting a black man kneeling in prayer in the swamp as attacking alligators bite him from behind. In the corner is printed "A Darky's Prayer, Florida." Leroi's message in full: "Dear Kenneth, Better start saying your preyers [sic], if you think you can play Chess while Millions struggle! Love Leroi 2 x." Fine.50

Based on this description, Syracuse bought the card, and added it to the LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) Collection. Other experts accepted the attribution as well. (I wonder how many other archival documents have questionable attributions?)

But the authority of previous attributions was only one reason I'd failed to more fully consider the attribution. When I wrote the original essay, I wasn't able to imagine that a White member of Koch's community would have sent that postcard. I should have known better — even if Berrigan didn't have anything to do with the postcard. Baraka's work from the period — especially Experimental Death Unit #1 (1965) — indicts the racism of the White world downtown. My failure points to two additional sites of interpretive difficulty: my naiveté ("complicity" might be a more accurate term) and the racism of seemingly progressive communities.

Another way to keep both problems live would be to ask: what happens when an attribution cancels an interpretation? What happens to the interpretation? Imagine a book of defunct interpretations — interpretations of misattributed paintings, of Ern Malley's poems and JT Leroy's stories. Would such a book be worth reading? What might we learn from such unintended fictions?

Over the last couple of weeks, I have been thinking a lot about an unrelated ambiguity. In Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963, 1964), Hannah Arendt likely mischaracterized Adolf Eichmann as an apolitical bureaucrat. (Recent scholarship has argued that he was a committed Nazi.) Would such a mischaracterization invalidate her account of the banality of evil? One could argue that her account would still apply to other Nazis. But my intuition is that the account would be correct — or at least useful — even if it didn't apply to anyone at all. How could that be true? Can an incorrect attribution or characterization lead to a correct interpretation?

Mistakes can be fortuitous. They can facilitate thinking that could not happen otherwise. I already regret mentioning Eichmann in Jerusalem — what a fraught analogy! — but I will let it stand, as I've decided to let my original essay stand. (If Sturm had somehow been able to notify me a day earlier, I would have written a much different essay.) I don't know whether my account of postcards, frenemies, structural racism, and ambivalence has interpretive power beyond the context of one difficult to interpret — and attribute — primary source. But the risk of being wrong is worth the chance of being right.

***

I thank Rachel Applebaum, Andrew Epstein, Dan Sinykin, and Johanna Winant for comments on drafts of this essay. I also thank Brian Cassidy, Glenn Horowitz, Sidney F. Huttner, Mary Catherine Kinniburgh, and Jeff Maser for discussing the postcard's provenance and related matters.

Joshua Kotin (@joshua_kotin) is Associate Professor of English at Princeton University. He is the author of Utopias of One (Princeton University Press, 2018) and the director of the Shakespeare and Company Project.

References

- "A Darky's Prayer, Florida," Curt Teich Postcard Archives Digital Collection, Newberry Library.[⤒]

- For a discussion of the stereotype, see Patricia A. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies (New York: Anchor, 1994), 31-40.[⤒]

- LeRoi Jones to Kenneth Koch, 1 April 1965, box 1, folder 5, Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.[⤒]

- The postmark includes two internal post office codes: "10A" and the "I" after "New York." The "10A" identifies the canceling machine that canceled the stamp. I haven't been able to determine the significance of the "I." I thank John Becker and the Stamp Community Forum for responding to my questions about the postmark.[⤒]

- See David Pilgrim, "Why I Collect Racist Objects," Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia (2012); Henry Louis Gates Jr., "Should Blacks Collect Racist Memorabilia?" The Root (June 3, 2013); Adeel Hassan, "A Postcard View of African-American Life," The New York Times (February 24, 2018).[⤒]

- Amiri Baraka, Autobiography of LeRoi Jones (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1997), 234.[⤒]

- Ibid., 233.[⤒]

- Kenneth Koch, "Fresh Air," in Thank You and Other Poems (New York: Grove, 1962), 56.[⤒]

- Lorenzo Thomas, Don't Deny My Name: Words and Music and the Black Intellectual Tradition (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 113. For a critique of Thomas's reading of "Black Art," see Joshua Kotin, "Poems That Kill," Critical Inquiry 47, no. 3 (April 2021): 456-476.[⤒]

- Kenneth Koch, The Collected Fiction of Kenneth Koch (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2005), 17.[⤒]

- Laura Steele, review of The Collected Fiction of Kenneth Koch, by Kenneth Koch, part 2, Intercapillary Space (July 2006).[⤒]

- See Ted Berrigan, review of Art and Literature, Kulchur 15 (Autumn 1964), 93-95. For a discussion of the role of postcards in New York School poetry, see Terence Diggory, "Genre," in Encyclopedia of the New York School Poets (New York: Facts on File, 2009), 185-188.[⤒]

- According to the United States Flag Code, "[t]he flag should never be displayed with the union down, except as a signal of dire distress in instances of extreme danger to life or property." See "Respect for the Flag," 4 U.S.C. §8 (2018).[⤒]

- . For an account of Baraka's name change, see Baraka, Autobiography, 376-377. [⤒]

- Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Ballantine, 2015), 403. Leon Forrest's novel Divine Days (1992) features a character named Leroy 5X Jones. See Leon Forrest, Divine Days (Chicago: Another Chicago Press, 1992).[⤒]

- Baraka, Autobiography, 293.[⤒]

- Ibid., 294.[⤒]

- Vivian Gornick, "The Press of Freedom: An Ofay's Indirect Address to LeRoi Jones," Village Voice (March 4, 1965). The exchange at the Village Vanguard anticipates an exchange in The Autobiography of Malcolm X. "'What can I do?'" a White college student asks Malcolm X. "'Nothing,'" he replies. See Malcolm X, 292. Spike Lee dramatized the exchange in Malcolm X (1992), changing many details.[⤒]

- Baraka, Autobiography, 285.[⤒]

- Ibid., 286.[⤒]

- Ibid., 263. "Profiling": "to show off; to posture or preen." See definition 5b in "Profile, v," OED Online (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).[⤒]

- Baraka, Autobiography, 263-265.[⤒]

- The scholar Sean Lovitt found it there as well. "It's unclear," he writes, "if Baraka's signature, an obvious reference to NOI chosen names, represents an intermediate stage between his identity as LeRoi Jones and his self-designation as Amiri Baraka. To my knowledge, this is the only instance of this signature. The signature and message to Koch could be a bit of role-play, or it could be an example of Baraka's growing militancy." See Sean Lovitt, "Mimeo Insurrection: The Sixties Underground Press and the Long, Hot Summers of Riots" (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2020), 137.[⤒]

- Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse Libraries, email message to author, March 26, 2021.[⤒]

- Jessica Mitford, "The Best of Frenemies," in Poison Penmanship: The Gentle Art of Muckraking (New York: New York Review of Books, 2010), 218.[⤒]

- Walter Winchell quoted in "Frenemy, n," OED Online. "Frenemy" recalls various accounts of friendship — from Ralph Waldo Emerson's idealization of the "beautiful enemy" in "Friendship" (1841) to Derrida's discussion of the "friend-enemy" in The Politics of Friendship (1994). See Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Friendship," in Essays and Lectures, ed. Joel Porte (New York: Library of America, 1983), 341-354; and Jacques Derrida, The Politics of Friendship, trans. George Collins (London: Verso, 2005). For a powerful account of the "doubleness of friendship" and the development of poetry in the United States, see Andrew Epstein, Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).[⤒]

- Bill Berkson, Since When: A Memoir in Pieces (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2018), 112.[⤒]

- Harry Gilroy, "Racial Debate Displaces Jazz Program," The New York Times (February 10, 1965), 47. What does Baraka mean by "cover story"? The phrase connects two accusations. First, Baraka is accusing Rivers of using his work with Black artists to conceal his complicity in White supremacy. (Rivers had designed and built the sets for Baraka's Toilet [1963], which was currently running at St. Marks Playhouse in the East Village.) Second, Baraka is accusing Rivers of using his experience of anti-Semitism to minimize the severity of anti-Black racism. ("I'm sick of you cats talking about the 6 million Jews," Shepp remarked at the forum; "I'm talking about the 5 to 8 million Africans killed in the Congo.") This second accusation illuminates an additional context for interpreting the postcard: tensions between African Americans and American Jews in New York in the mid-1960s. Koch, who was Jewish, would have recognized the postcard's "while millions struggle" as a reference to these tensions.[⤒]

- Harold Cruse, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual: A Historical Analysis of the Failure of Black Leadership (New York: New York Review of Books, 2005), 487. The New York Times also described Shepp's exchange with Rivers. See Gilroy, 47.[⤒]

- Adam Phillips, "Against Self-Criticism," London Review of Books 37.5 (March 5, 2015).[⤒]

- Lerner glosses Allen Grossman: "Poetry arises from the desire to get beyond the finite and the historical — the human world of violence and difference — and to reach the transcendent or divine. You're moved to write a poem, you feel called upon to sing, because of that transcendent impulse. But as soon as you move from that impulse to the actual poem, the song of the infinite is compromised by the finitude of its terms." See Ben Lerner, The Hatred of Poetry (New York: FSG, 2006), 8.[⤒]

- Phillips.[⤒]

- William Empson identifies ambivalence as the seventh and most extreme type of ambiguity, citing Richard Crashaw's use of "discharge" in his translation of "Dies irae" (1646). The word, Empson writes, "involves a curious ambivalence of feeling" — a combination of "sympathy" and a "contempt so terrible as to degrade also the contemner." See William Empson, Seven Types of Ambiguity (London: Chatto and Windus, 1949), 243.[⤒]

- Helen Vendler, Our Secret Discipline: Yeats and Lyric Form (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), 17.[⤒]

- Ibid., 17, 22.[⤒]

- Sigmund Freud, Three Case Histories, ed. Philip Rieff (New York: Touchstone, 1996), 34-35.[⤒]

- The "true recipient" of the first known postcard, Liliane Weissberg writes, "was not the addressee but people reading the mail en route to its delivery." Derrida describes the postcard as "half-private half-public, neither the one nor the other." See Liliane Weissberg, "Postcards from the Avant-Garde," MLN 132 (2017): 586; Jacques Derrida, The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 62.[⤒]

- In Utopias of One (2018), I develop a theory of interpretive difficulty that is not based on ambivalence. See Joshua Kotin, Utopias of One (Princeton University Press, 2018), especially 11-12.[⤒]

- Berkson mentions a missed encounter between Baraka and Koch in 1968: "During the Columbia University student protests in 1968, Kenneth Koch organized a reading in a campus lounge with a few poets, including Allen Ginsberg and me, to express solidarity with the protesters. Amiri was invited but never showed up, although Allen, pacing back and forth and wondering aloud at Amiri's absence, tried to every which way to conjure him." See Berkson, 112.[⤒]

- Frank O'Hara to John Ashbery, 26 April 1965, box 3, folder 31, Allen Collection of Frank O'Hara Letters, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library. O'Hara's letter to Ashbery warrants its own essay in this cluster. After noting Baraka's lack of interest, O'Hara writes: "He has founded something called the Black Arts Theatre and school for a lot of Negroes to learn how to do a lot of theatrical things for each other. Perhaps only because I find it so personally disappointing, it reminds me only of 18

9667." The racist condescension, the real hurt — both are easy to interpret. But the revised date? To complicate matters: I have not yet been able to consult the original letter. I've only read a copy transcribed by Donald Allen. Is the mistake Allen's or Hara's? Is it a mistake at all?[⤒] - Johanna Winant, email message to author, May 26, 2021.[⤒]

- Nick Sturm, email message to author, May 26, 2021.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Jordan Davis, Review of The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, Chicago Review 52, no. 2-4 (Autumn 2006), 355, 354.[⤒]

- Alice Notley, email message to author, May 31, 2021.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Jeff Dolven, email message to author, May 31, 2021.[⤒]

- Jeff Maser, email to the author, March 29, 2021.[⤒]