Interpretive Difficulty

Of all the interpretive experiences, and of all of the analytical puzzles, that might have baffled me, I had never envisioned this one: attempting, as an English professor, to understand the concept of intent in Criminal Law 101. Crim's the course everyone looks forward to in 1L, the first year of law school, supplying narrative relief from Civil Procedure and Contracts and the raw material for every Law and Order spin-off ("These are their stories. DUN DUN"). Broken down into discretely practicable chunks, rage and tragedy become aggravated assault, manslaughter, and homicide, rendered manageable for prosecutor, defense attorney, and jury alike. Along with identifying the culpable state of mind (such as intent), all you need to do is find the evidence and make some basic distinctions. Define the alleged criminal conduct, attendant circumstances, resulting harm, and potential defenses . . . and you're on your way to trial.

But a few years ago, sitting in a lecture hall and trying to grasp the fundamental difference in the Modern Penal Code between acting "purposely" versus acting "knowingly," I was in a panic. I kept drawing a blank whenever we were supposed to distinguish between them. What was the difference between a purposeful mental state and a knowing one, and how was I supposed to determine it? I forced myself, mechanically, to reread the definitions of the terms and apply the rules to the facts of the case, as if I had lost intuitive knowledge of how language worked. Why, in law school, did this type of analytical, interpretive puzzle feel not just unfamiliar, or difficult, or wrongheaded — but unsolvable?

The experience was even stranger because the concept of intention was something I had been thinking and talking about for a while, an idea (I thought) I grasped. When enraged husband Frank Shabata happens upon his wife lying with her lover under a white mulberry tree and kills them both with "his murderous .405 Winchester," that lethal act in Willa Cather's O Pioneers! was one I knew how to tackle.1 Cather is exploring the limits of what Frank could and could not imagine — what he knew — about his own designs: "Though [Frank] took up his gun with dark projects in his mind, he would have been paralyzed with fright had he known there was the slightest probability of his ever carrying any of them out."2 According to the Modern Penal Code, Frank has the requisite purpose to kill (those "dark projects in his mind"). But Cather's complex sentence is slippery. Frank's purpose looks more dubious if conjectural knowledge ("had he known") of "the slightest probability" of acting on his purpose would have "paralyzed" his acting. His knowing and his purpose seem impossible to disentangle. Parsing such a scenario by cleanly dividing up Frank's mental state into boxes labeled "purposely" or "knowingly" was beyond my reach.

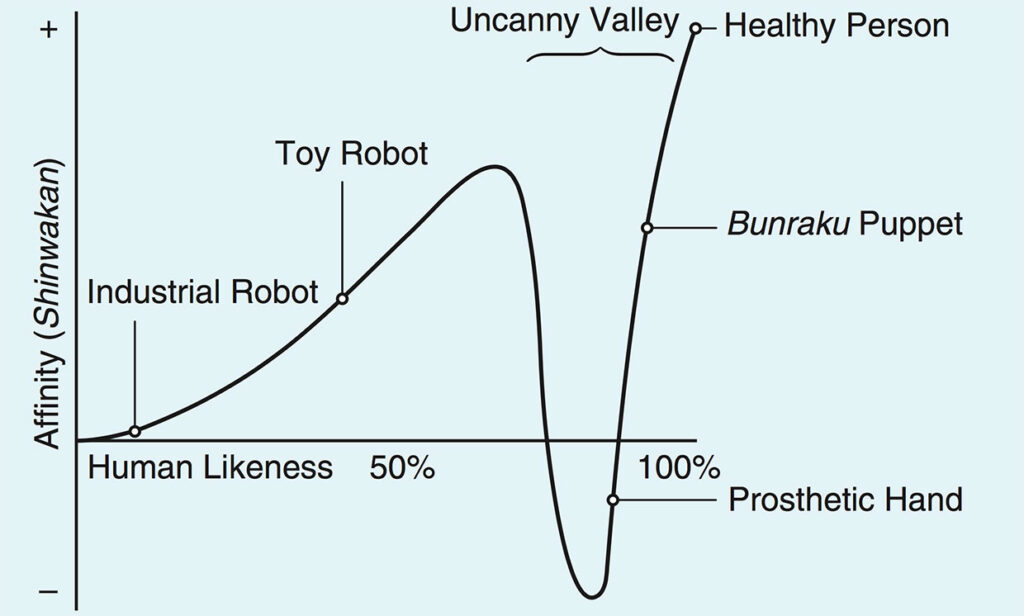

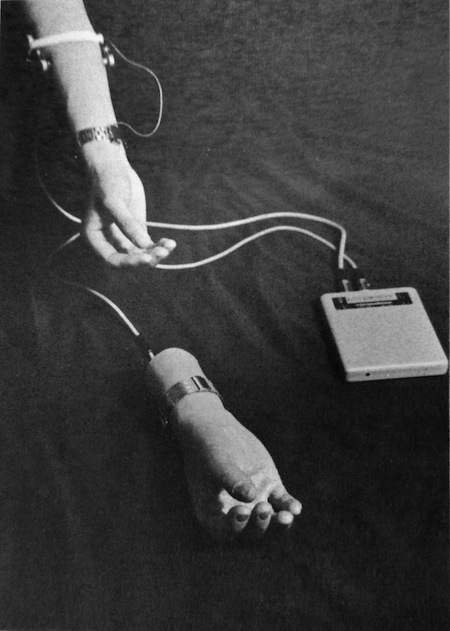

It took a long time to figure out why this interpretive situation so vexed me, but now I have a clue ("DUN DUN"). I had fallen into the interdisciplinary uncanny valley — a murky trap hiding between cognate disciplines. The "uncanny valley" is robotics theorist Masahiro Mori's term, indebted to Freud's unheimlich, for the increased aversion experienced when humanoid robots begin to more closely resemble human beings (Fig. 1). Rather than experiencing our kinship to these pseudo-humans as a steady rise, Mori explains, at some point, when a prosthetic robot hand starts to truly move like our own, "we experience an eerie sensation . . . we lose our sense of affinity, and the hand becomes uncanny" (Fig. 2).3 The robot hand takes on an aura that is corpse- or zombie-like — the uncanny valley is also the valley of the shadow of death — and we feel revulsion. As the animated robot comes to resemble us, becoming humanlike, the more "[it] could easily tumble down into the uncanny valley."4 Identifying with the corpse-like thing must be avoided, hence the disgust and other tactics we use to find a way past, or out of, or away from, the ghastly abyss.

Attending law school and earning a J.D. a bit later in life, already established in a humanities discipline, I came to realize that when we do interdisciplinary work, we are invariably crossing an uncanny valley between the disciplines, whether we mean to — purposely or knowingly — or not. In the cases I was reading, lawyers and judges were using familiar words in ways extremely close to my own, but not quite the same. It was a fuzzy, unpleasant semblance that somehow felt worse than simple incongruity. I wanted concepts like intention, purpose, and knowledge to be identical wherever I found them — freely mobile, substitutable whether in legal analysis or in literary interpretation. And many of those concepts did seem very close to one another in both literary criticism and legal analysis. And then . . . the cliff of criminal intent appeared in an alarming rush, and the uncanny valley had to be traversed.

For all the potential promise of interdisciplinary work, working in that void is frequently disagreeable. Years ago Stanley Fish contended that "being interdisciplinary . . . is not a possible human achievement," something like breathing in outer space without a spacesuit.5 You attempt to keep a "reflective distance" from disciplinary conditions (say, of law) "while still engaging in that practice," not recognizing that "once the conditions enabling a practice become the object of analytic attention," you have already begun "engaging in another practice."6 From Fish's perspective, as soon as I had started thinking about the fundamental difference between acting purposely versus acting knowingly in relation to Cather's novel I was neither doing law (because Cather's text is not trial testimony, a court decision, or a legal treatise), nor was I doing literary criticism (because the distinction between acting purposely versus acting knowingly has no purchase in, say, an issue of PMLA). So what was I doing?

Inadvertently leaping across the almost-identity between the disciplines would have been more pleasant, my aversion and confusion replaced with deliberate ignorance. Or "willful blindness," as the criminal lawyers say. But willfully seeing and learning to cross that valley, with all its risks and pitfalls, and sometimes tumbling down it, also had a particular kind of analytic value to me — and sitting in that law classroom was how I acquired it. I was in the process of writing a book, Modernism and the Meaning of Corporate Persons, which argues that the possibility that large collective organizations might mean to do what they do — and might mean like us, like persons — animated an astonishingly diverse set of American writers, artists, and theorists of the corporation in the first half of the twentieth century, stimulating a revolution of thought on intention. The ambiguous status of corporate intention provoked conflicting theories of meaning — on the relevance (or not) of authorial intention and the interpretation of collective signs or social forms — still debated today. Along the way, I decided that making my case about how corporations, as legal persons, have been understood to make meaning required learning more about how American lawyers know and mean. How could I talk about the legal concept of intention otherwise? Embracing 1L as a student was part of my research.

That path led to many more questions. Sometimes words with one meaning in literary scholarship or ordinary language took on a different — sometimes only slightly different — meaning in law. Unpacking criminal intent was just a taste. Examples proliferated, appearing in every course: "person," "personality," "prejudice," "formalism," "interpretation," "diversity," "performance," "speech." A straightforward approach to this kind of divergence is to chalk it up to disciplinary jargon or terms of art. As a field with its own rigidly policed boundaries and requirements for expertise, promulgated through texts upheld as precedents, law provides plenty of opportunities for terminological fastidiousness. Consider that the legal term "personhood" (the condition of being a person) is a relatively new introduction to English — the O.E.D. dates its first use to 1944. Before then, law used "personality" to capture the legal notion of being a person, and "personality" is still used by lawyers and judges in this way, along with the term "personhood." But, more familiarly, "personality," in both ordinary language and literary scholarship, means being possessed of individual qualities or characteristics. Legal language incorporated both the new meaning and the old. As it absorbed the common law more generally (massaging older ideas into newer forms), law retained archaic terms and, to this day, continues to employ them alongside our newer, more ordinary notions of a word like "personality."

Consequently, when I analyzed a legal decision about a corporation and saw both "personhood" and "personality" used freely in the text, I had two very different kinds of responses, befitting my disciplinary in-betweenness. As a legal scholar-in-training, I knew that these terms could be employed interchangeably in legal doctrine and should be interpreted as such. To proceed otherwise would be to ignore a fundamental aspect of conventional legal language. But as a literary scholar invested in asking how corporate persons came to be understood as meaning-makers, I recognized that either word might be deployed strategically (by a legal writer) to rhetorically highlight different qualities of a corporate person: its legal aspects versus its more humanlike qualities. Which interpretive path was I supposed to follow — and why? Of course, knowing how the term was being used in any instance required teasing out its meaning in the context of everything else the writer was arguing. But, granting that, a challenging puzzle still lingered. Legal analysis required that I interrogate words and their usage in a very different way from literary analysis. Either I was supposed to see terms (in law) as deriving their meaning from precedent legal authorities, or (in literature) as aligning with closely related usages and concepts. A problem that initially appeared to require a simple translation of jargon actually entailed an entirely different analytical process, leading to the looming plunge down the interdisciplinary, uncanny valley. (Fig. 3)

Unlike Wile E., scholars unfortunately find ways to glide past this difficulty all the time. Some might not see the difference at all, either through ignorance or scholarly incompetence (less interesting) or the beforementioned willful blindness (more interesting). In the latter case, one might ignore the discrepancy — or, more adeptly, dance around it, embracing the "freedom of movement" of midair flight, as Bruno Latour puts it, released from disciplinary foundations.7 Typically, one then observes the limitations of disciplinary difference and acknowledges what cannot be equated in any other way — but nonetheless purports to absorb a part of a neighboring discipline to radically change his or her own.

For an example, take Latour's claim that unlike traditional sociology, Actor-Network-Theory frees social theorists from their conventional "figurations" of agency by embracing the liberating methods of another discipline — specifically, narratology. "Literary theorists," writes Latour, "have been much freer in their enquiries about figuration than any social scientists."8 By adopting the concept of narrative function — that a plot of any fairy tale, play, or novel advances not by characterological qualities but by a character's purpose and action in the sequence — sociologists will increase "their freedom of movement," to become "less rigid, less stiff in their definition of what sorts of agencies populate the world."9 Relaxed accounts of agency supposedly rejuvenate sociology. But identifying narrative function as such only makes sense in service of a larger, inherently disciplinary aim: trying to understand narrative and how it functions. Narratology's value to sociology breaks down as soon as the object of study expands beyond the study of plot. Unless you're willing to accept the idea of a higher being authoring the story of all human fate, no narrative structure or literary order could be imagined as composing all the social world and its actors — or actants. Picking out the innards of narratology while ignoring the frame of narrative that makes it meaningful is not embracing narrative theory but manufacturing something new, for sociology, out of another discipline's bits and pieces. That something new might or might not be an improvement on the previous sociological paradigm, but it has no bearing on, or even real conceptualization of, literary studies as a discipline. The interdisciplinary uncanny is not faced if no difference — however small — is identified and understood as such.

Julie Stone Peters aptly describes yet another approach to avoiding what I'm calling the interdisciplinary uncanny valley, through a kind of disciplinary projection. When law sees literature, or vice versa, each projects onto it what it wants to see, absorbing the silhouetted contrast of her own discipline's lack. "[L]aw and literature might be seen as having symptomatized each discipline's secret interior wound: literature's wounded sense of its insignificance . . . law's wounded sense of estrangement from a kind of critical humanism that might stand up to the bureaucratic state apparatus."10 Literary studies plays an imaginative psychic game, gaining a bolder view of itself at a moment when, as Michèle Lamont notes, the discipline is undergoing a "demographic decline" that requires responsive solutions.11

But avoidance of the interdisciplinary uncanny valley was not my problem here. Since my own blindness, or at least my analytical inadequacy, was distressingly apparent to me, there had to be another explanation for what was happening. Maybe I was just confused by legal study generally (entirely possible — I still can't hold the Rule Against Perpetuities in my head for more than five minutes). Or perhaps I didn't know which discipline I was in at the moment of reading such a case — and was trying to have it both ways at once (also likely). Or maybe, with my home discipline of literary studies so eager to appropriate from others, and having lost the cultural capital it previously held, I had lost track of why I valued literary study at all (a disciplinary crisis of faith). Finally, maybe I was finding myself tempted by a certain nominalist rigidity. Upon seeing words like "personality" or "intent," I didn't want to alter my sense of their meanings. Whatever disciplinary context I found myself in, I thought I knew what intention meant wherever I was.

There is some truth to all of those possibilities. But that last option is probably the closest to my situation in 1L, albeit in a way I didn't understand at first. Specifically, I was reacting to the pragmatic decision systemized in the Modern Penal Code (MPC) of avoiding the word "intent" in its definition of culpable mental states, traditionally known as mens rea, the concept of "guilty mind" or criminal intent. The MPC was a major legal theoretical endeavor, produced by the American Law Institute around the middle of the twentieth century, designed to advise legislatures on how to reform their archaic morass of crime laws; most states adopted parts or all of the MPC in later decades.12 After widely surveying US criminal laws, the MPC drafters concluded that there was "no discernable pattern or consistent rationale" justifying why any particular mental state — any particular intent — attached to any particular crime.13 Faced with this jumble, they decided to "draw[] a narrow distinction between acting purposely and knowingly, one of the elements of ambiguity in legal usage of the term 'intent.'"14 That is, they divided the concept of intent into two components each with strict definitions, leading to the solution that so bothered me: "A person acts purposely" if it is his "conscious object" to cause a certain result (MPC§2.02[2][a]), while a "person acts knowingly" if "he is aware" that "his conduct will cause such a result" (MPC§2.02[2][b]).15 Their hope was that this circumscribed language would "enhance[] clarity in [legislative] drafting," eliminating "the obscurity with which the culpability requirement is often treated."16

Avoiding obscurity in conceptions of intention is likely a necessary and laudatory goal of criminal law, a way to avoid vague and unjust applications for defendants.17 But in literary study, withholding judgment on this issue — on when exactly an author writes purposely or knowingly — is something critics must do reflexively when making claims to interpret a text. It's hard to imagine a practice of literary study without doing so. We take for granted that trying to identify an authorial, psychological distinction between purpose and knowledge gets us nowhere, or nowhere interesting, short-circuiting the entire interpretive endeavor. On Fish's account, I had stumbled upon one of the basic premises of my discipline that could no longer be interrogated at all, for "to conceive of yourself as a member is to have [ . . . ] forgotten that those are questions you can seriously ask."18 Another way of putting it is that, as a literary scholar, I already knew that when an author has written a text, that text encompasses everything she purposely meant to write, whether or not any particular element of the text — its tropes, themes, contextual allusions, or whatever else — was meant knowingly by her.

Whereas criminal law understands intention as a mental state potentially discoverable as a positive fact, a piece of evidence to be sought and acquired (whether or not anyone ever truly finds it), literary study understands intention in the text as a story to be told about what happened, a story that I, an interpreter, am striving to figure out (whether or not anyone ever truly finds it). Literature's account of intention differs from law's not exactly or only in an epistemological sense (about how we come to know intention, or whether we can be sure of the knowledge we seek and find). Rather, these two fields diverge in their very conception of what intention is and how it operates: as an internal mental state (in law) versus an answer to the question "why this?" ( in literature). What my 1L Criminal Law course required me to do — for reasons entirely sound in the realm of criminal law — was an interpretive analysis of intention that I had been trained to believe, and that I was training my students to believe, made no sense at all. In the process of being taught what I could not make myself do, I was remembering what I had forgotten I believed.19

Moreover, I realized, no simple resolution exists that would correct legal analysis or literary scholarship to make "intention" work in both disciplines in the same way. The interdisciplinary uncanny valley exists. It is something I approached, face to doppelgänger face, in a linguistic sign whose signified slightly diverged from the one I understood. In some basic sense, the two disciplines must use a term like "intention" in ways that overlap substantively, but also diverge substantively. They use the term for different purposes, and so their perspective on it must differ. The MPC drafters believed that any interpretive ambiguity or disagreement over the term "intentionally" could be very damaging to legality, creating unfair or wildly varied results. Judges — and juries — would be forced to make sense of the term in their own way following unpredictable beliefs, legal principles, and circumstances of the cases they considered. And literary scholars recognized (as early as Wimsatt and Beardsley in "The Intentional Fallacy"), that to insist on a writer's explicitly articulated purpose or testified knowledge rarely led to a compelling interpretation of a text — if it could even be understood as an interpretation at all.

All of which leads back to a reading of Cather's O Pioneers! I chose that novel as my example because Joshua Dressler's Cases and Materials on Criminal Law, Sixth Edition, one of the most commonly assigned casebooks in American law schools, excerpts the two chapters of Frank's carnage to illustrate how a killing "committed recklessly" might be downgraded from murder to manslaughter, if "committed under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance for which there is reasonable explanation or excuse" (MPC§210.3[1][b]).20 Thus, the casebook editors title this section: "Murder versus Manslaughter: A Literary Problem."21

In the casebook, Frank's psychological disorganization serves as evidence, if deemed "reasonable," for a defense against his intent to commit murder. He might have taken "up his gun with dark projects in his mind," but he truly did not know his purpose, or at least his purpose and knowledge were not aligning intelligibly when "the gun sprang to his shoulder, he sighted mechanically and fired three times without stopping, stopped without knowing why. Either he shut his eyes or he had vertigo. He did not see anything while he was firing."22 As Frank experienced the scene, the gun acted without him purposely controlling it (it "sprang to" him, "he sighted mechanically"), and he couldn't comprehend or even see what was happening ("without knowing why"). Later, learning that Frank had been sentenced for ten years in the state penitentiary, "guilty of killing without malice and without premeditation," we know that his provocation defense must have worked to reduce the charge.23

But Cather's investment in the concept of intention lies deeper than that. Frank's act of killing comes toward the end of a novel exploring the limits of understanding mental states as equivalent to intentions. Contrasting the aim those chapters were designed to perform in my Criminal Law casebook with the role they play in O Pioneers! as a whole underscores the point I have been striving to make here. Contra to the casebook editors' section title, the "literary problem" here is not a literary problem at all. The problem is attempting to understand a work of literature through a legal lens.

Even as a young Western farmer, Alexandra Bergson, the novel's protagonist, "knew exactly where she was going and what she was going to do next," while at the same time, she has to narrate that prosperous future to realize her intentions: "I have to keep telling myself what is going to happen."24 Acting purposely and knowingly, while telling herself the story of her intentions, makes her a wildly successful farmer, even as she fails utterly to predict "[t]he story of what had happened" when Frank kills her younger brother, "written plainly on the orchard grass."25 Examining Alexandra's situation, that is, why ideas in our head — mental states, mens rea — do not always align with "what is going to happen" or with "the story of what had happened," is arguably Cather's larger purpose. In seeing that point, we can also see the interdisciplinary uncanny valley laid bare. Which is to say, we can see why differentiating between how Frank acts purposely versus knowingly might be a question law needs to answer — and for that reason, that law needs to value. But it is not a problem literary study could ever value or answer. Which is also, I think, why the distinction between purposely acting and knowingly acting will remain a concept I always forget to learn.

Lisa Siraganian (@ProfGirl) is the J. R. Herbert Boone Chair in Humanities, Associate Professor, and Chair of the Department of Comparative Thought and Literature at Johns Hopkins University. She is the author of Modernism's Other Work: The Art Object's Political Life (Oxford, 2012), shortlisted for the Modernist Studies Association Book Prize (2013), Modernism and the Meaning of Corporate Persons (Oxford, 2020), and is co-editor of The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Tenth Edition, Volume D (1914-1945), forthcoming 2021. This piece is part of a larger project on crossing the interdisciplinary looking glass. She managed to pass Criminal Law.

References

- Willa Cather, O Pioneers! ed. Susan J. Rosowski, Charles W. Mignon, and Kathleen A. Danker (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 233.[⤒]

- Ibid., 234.[⤒]

- Masahiro Mori, "The Uncanny Valley," trans. Karl F. MacDorman and Norri Kageki, IEEE Spectrum (12 June 2012). Originally published in Energy 7, no. 4 (1970): 33-35 (in Japanese). [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Stanley Fish, "Being Interdisciplinary is So Very Hard to Do," Profession 89 (1989): 15-22. Reprinted in Stanley Fish, There's No Such Thing as Free Speech: And It's a Good Thing, Too (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 18-19.[⤒]

- Ibid., 20.[⤒]

- Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 55.[⤒]

- Ibid., 54.[⤒]

- Ibid., 55.[⤒]

- Julie Stone Peters, "Law, Literature, and the Vanishing Real: On the Future of an Interdisciplinary Illusion," PMLA 120, no. 2 (2005): 448.[⤒]

- As Michèle Lamont writes, "The effort to broaden the audience, to conduct 'cross-disciplinary conversations,' is a logical response to the demographic decline of the field of English literature"; How Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic Judgment (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), 75. Although see also Jonathan Kramnick, observing that "[a]rguments that undercut the rationale for separate disciplines of study apply unevenly to those with depleted capital," in Paper Minds: Literature and the Ecology of Consciousness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 18.[⤒]

- Paul H. Robinson and Markus D. Dubber, "The American Model Penal Code: A Brief Overview," New Criminal Law Review: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal 10, no. 3 (2007): 319-341.[⤒]

- American Law Institute [ALI], Modern Penal Code and Commentaries (Official Draft and Revised Comments) (Philadelphia: American Law Institute, 1985), 230, fn. 3.[⤒]

- Ibid., 233.[⤒]

- Ibid., 225-226.[⤒]

- Ibid., 234, 230.[⤒]

- According to the MPC drafters, retaining the word "intention" "may well perpetuate the present ambiguity," which was why "'purpose' was selected as the better term" (ibid., 235, fn. 11).[⤒]

- Fish, "Being Interdisciplinary," 20.[⤒]

- See Fish: to function in a discipline you cannot "hold its differential (nonpositive) identity in mind"; rather, that core identity is something one "must always forget when entering" a discipline's boundaries (ibid.). [⤒]

- ALI, Modern Penal Code, 120. [⤒]

- Joshua Dressler and Stephen P. Garvey, Cases and Materials on Criminal Law, 6th ed. (St. Paul, MN: West, 2012), 291-294. [⤒]

- Cather, O Pioneers!, 234-35.[⤒]

- Ibid., 252.[⤒]

- Ibid., 13, 55.[⤒]

- Ibid., 240.[⤒]