Bernadette Mayer

In 1968 or 1969, Bernadette Mayer spent part of an afternoon reading The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 by Andrew Sarris.1 She hated it. She wrote a letter to her boyfriend, Ed Bowes, who was traveling around the country working as a filmmaker. "Dear Ed, I read the Andrew Sarris book for two hours. Don't I have anything better to do?" A speech bubble is drawn next to the phrase "Dear Ed"; it says, "BE PREPARED THIS IS AN ESSAY" in printed capital letters. "SEE?" A little arrow points to an epigraph in the top margin of the page, written in excellent cursive: "'Meaning is a Physiognomy' —Ludwig Wittgenstein."

Andrew Sarris is now known for popularizing auteur theory in the United States — the theory that movies could express the individual personalities of their directors. Sarris's figure first rose to prominence in part because Pauline Kael wrote a famous essay criticizing him in 1963. "I had been writing articles," Sarris explains in the introduction to The American Cinema, "for seven years without fueling any fires of controversy, but on this occasion a spark was ignited in far off San Francisco by a lady critic with a lively sense of outrage."2 Kael was one of the most famous and influential film writers in the US, and especially popular in New York and San Francisco literary circles.3 Sarris was popular with an adjacent, overlapping group, college students and amateur film buffs, and he ultimately rallied his readers against hers: he offered his book as an antidote to the power of a certain kind of critic, whom he described metonymically as the "condescending cackle one hears in so-called art houses."4 Insofar as this line refers to a type of film writer, and not a phantasmagoric memory of a bad time at some event, it refers to a Pauline Kael type. Kael, for her part, carefully argued that Sarris's theory of film, in addition to being incompetently written, was a pseudoscientific system that justified his personal affinity for the creative work of men. 5"Can we conclude," asked Kael at the end of "Circles and Squares," "that in . . . the United States, the auteur theory is an attempt by adult males to justify staying inside the small range of experience of their boyhood and adolescence — that period when masculinity looked so great and important but art was something talked about by poseurs and phonies and sensitive-feminine types? . . . I ask; I do not know."6 Suppose that the answer to this question is yes, and that Kael was right about Sarris: his writing was clumsy and witless; his arguments were pseudo-analytical, quackish nonsense; he chose auteurism because it was a pragmatic solution to his deep, nervous admiration not for the heroic figure of the artist but for the familiar figure of the professionally successful man. If Sarris's work was about protecting American masculinity from the rise of "cackling" art-house discourse, then Kael's critique of Sarris was a way of wading into a popular conversation that was supposed to be between men arranged in an intimate hierarchy; top-down, and without enough space between them for her criticism and its growing audience.

Written about five years later, and addressed to an audience of one, Mayer's letter about American Cinema is like a perfect inversion of this movement. If it is a critique, it is one with a funny, resolutely minor, inward mode of urgency. Suppose the real problem with auteur theory is that Bernadette Mayer once felt compelled to pick up this book about it. "Don't I have anything better to do?" Mayer wondered. If Kael's feminist critique of Sarris was a form of publicly wading in, Mayer's letter wonders privately about the possibility of wading out. "Why is that book so necessary?" Mayer asked, registering that she and her friends were reading Sarris like it was mandatory. She answers her own question: "It's exactly because movies are not art but the industry of making movies, that is, leisure work." Mayer suggests that the point of Sarris's book is not the argument he makes, that some movies are art and some directors are artists. The point is that people seem to need movies to be art and directors to be artists. Movie-watching is a prototypically passive sort of leisure, which means it can make people hungry to do something that feels like work.7 The powerful thing about auteur theory is that curating, evaluating, and ranking the personalities of famously successful directors feels like work.8 So Sarris's theory was popular because it offered viewers a way to cognitively exert themselves at the movies — by prompting them to be skillfully and systematically attentive to the quality, consistency, and effect of some famous man's creative personality. Mayer's problem with this is expressed throughout her letter as an alternately fed up and collapsing tone: this isn't the kind of work she feels like doing. She concludes her essay (or "'ESSAY'") with the suggestion that movies themselves could undermine the gravitational, disciplinary power of celebrity "auteurs" as a concept, or at least the particular subdivision of that power represented by the "Sarris book": "There must be a very natural and easy way of milking the way movies have to be made — a way that's contrary to ideas like 'getting the cameraman to do what I want' . . . a way that would eliminate all film criticism for good or make it so confusing that nobody could ever think of film as an art again."

Mayer never finished this utopian idea about the right way to make movies. Instead, she stopped to ask for feedback from Ed. "What do you think of that?" Then her thoughts were drawn away by a different, but distinctly related, task: the ongoing development of her own writerly personality. "I think I'll translate that into writing and make it my new aesthetic," she closes, turning into herself. Writing, unlike filmmaking, is not an intrinsically collaborative medium. It involves long periods of cloistered, asocial introspection and possessive, self-involved solitude. This is why the author is such a convenient metaphor for the deliberate, individual artist — all "authors" are already, in a profoundly basic way, "auteurs." But Mayer suggests that there is a "natural and easy way of milking" the way writing has to be made — a way that could frustrate critical or cultural attempts to turn a writer into a famous author.

Some 40 years later, the poet Adam Fitzgerald asked her, "how does it feel to have an ARCHIVE, Bernadette Mayer?" She said, "it feels very self-important."9 This answer, followed by a laugh the interviewer describes as an "infectious cackle," expresses some buoyant ambivalence about the idea that her large archive of unpublished work at UC San Diego is a sign of her literary seriousness or success. How "important" is she, really? Academics often call Mayer "understudied" — this word can mean that literary studies is extractive and an author's work is rich. When critics call her work "understudied," they imply a normative proposition that more people should read and study it (which I endorse, as a suggestion). But "understudied" might also be deployed, perhaps more powerfully, as a neutral description of Mayer's literary signature. Her best-known work, Midwinter Day (1982), is an aesthetically modernist epic about a single day of her own life and it begins with the same word Ulysses does: "Stately." What if "understudied" was a way of saying something simply true?

Mayer's poetry about her life is poetry about being a writer who is less eminent than James Joyce. This, to be clear, would make her more indispensable, not less. From a certain angle, "less eminent than James Joyce" is the general condition of the educated, postwar American literary author, the obligatory premise of their whole enterprise. I'll put it another way. When Mayer says that having an archive "feels very self-important," consider the possibility that she is not self-deprecating, just telling the truth: her archive feels very self-important. Or, more elaborately: her collected papers, letters, poems, and ephemera index her hard-fought arrival at a particular form of lyric self-belief. The academic absorption of literary modernism in the decades before Mayer attended college shifted the cultural meaning of literary experimentation, importing demands of an implicitly scholarly audience. (In a 2001 interview with Daniel Kane, Mayer reflected on the imperatives of literary academicism this way: "you have to use words like 'fractal' and 'epistemological,' and you have to remember what they mean!"10) Mayer's writing managed twin agendas, not identical but fraternal: to lean heedlessly away from legitimating institutions, scholarly or popular, and to be "important" anyway. The resulting poetic persona speaks in a contradictory tone: an ardent deadpan, a mellow grandiosity, a barefaced, larking seriousness. We might understand Mayer's "self-important archive" as an attempt to short-circuit the pop- and high-cultural processes that would otherwise, for someone like her, sustain the figure of the "important," hot, serious, "fractal" literary writer as a perpetually receding object of obsessive analysis, aspiration, or desire. Maybe this is why she has been such a celebrated teacher and heroic figure to other avant-garde women writers especially.

"Isn't there a danger, though," Mayer was asked in 2001, "of suggesting that women poets more naturally tend to do things like collaborate and not get attached to authorship? Isn't that essentialist?"

"A desire to make a name for yourself in our culture really fucks men up," Mayer responded, "so I have no problem with celebrating the idea that women might naturally care less about that."11

***

In 1967, after she graduated from The New School, Mayer began to work and socialize with people in the New York City poetry and art scenes, meeting artists and writers she admired and often finding them unpleasant to be around. Ed Sanders, longtime member of The Fugs and 1967's face of the counterculture,12 once came over to her at a party and said, "you wanna be the next slum goddess of the Lower East Side?"13 Either he was asking for sex by quoting his own song lyrics, or asking Mayer if she wanted to be profiled in "Slum Goddess," a recurring feature in The East Village Other that ran short profiles under large, dramatically lit photos of cool New York women, especially reputed muses like Edie Sedgwick and Suze Rotolo. (It was supposed to be "the counterculture's answer to the Miss America aesthetic."14)

Increasingly convinced that "everybody was kind of stupid,"15 Mayer decided to leave the city. She moved to Great Barrington, Massachusetts to live by herself and write numerous, undated letters to her boyfriend. (That winter, Ed Bowes regularly drove hours in bad weather to see her, often asking her to come back, but she always refused.) She wrote to him about what she was writing, reading, and watching on television, and how it was all contributing to the intensification of a personal crisis. "Why should I live in New York if I don't want to see people," she once wrote. "Why do I like to see people and not be happy after I have seen them." She wondered if she was becoming "the kind of respectable middle aged person I hate most of all." Or, "maybe I'm becoming the new kind which is just as hateful." She wondered simply, "am I turning into a shit." She confessed, "I am afraid of my own person." She supposed that people were "going to hate [her]" for leaving the city. She supposed that her boyfriend's life, no matter where he was, was lived "in the middle of a thousand people who every minute . . . think you're wonderful." She concluded finally that she was "Emily Dickinson. Except that I fuck a lot." She asked Ed, "What do you think." Most of her letters went unanswered. When Ed did write back to her, he wrote with compliments: "What a letter," he once remarked, "that's real writing!"

Eventually, Mayer ran out of money; she moved back to New York where it would be easier to find paid work teaching poetry workshops. Shortly after she returned, she approached Holly Solomon and asked her to fund a new project, one that she had been, according to the pitch letter, "thinking about for some time." She wanted to shoot an entire roll of film each day for a month, and write about the experience of taking, developing, and looking at these photographs of herself, her surroundings, her friends, her daily life. Solomon liked the idea, and Mayer carried out this experiment in July 1971 — the project was titled Memory. It comprises over a thousand snapshots and a hundred pages of poetry, structured like a diary (entries appear below dates). Memory's representation of ordinary life stands out because it is a paradox: the work is physically monumental. It was first exhibited at the Greene Street Loft gallery in 1972. Over one thousand photos were displayed in a huge grid on the wall, and a six-hour audiotape recording of Mayer reading the entire work aloud, in a richly boring cadence, played on speakers.

In the 50s and 60s, poets started selling poetry on LP, collaborating with Steve Allen and Bob Dylan, taking thousands of photographs of themselves and sending them, signed, to bookstores, cafes, and clubs across the country. I read Memory as an extension of Mayer's own fraught practice of personal recording, her habit of live-capturing as much of her everyday life as possible with the help of newly efficient, portable, and affordable electric machines: cameras, recorders, typewriters. In Memory, "everydayness" is the gendered social flipside of a new model of literary fame. As these technologies made it possible for some poets (Dylan Thomas, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg) to become a new kind of famous, they also make it possible for others to become a special kind of ordinary.

Like Mayer herself, Memory has sustained an oxymoronic cultural status for a curiously long time. A.D. Coleman called its first installation "astonishing" in The Village Voice, while a reviewer of the first book edition called it "[a]n underground classic," adding, "I don't like the phrase . . . but I can't see how it can be avoided." The copy on Siglio's 2019 publishing announcement claimed that Memory's contribution to conceptual art was "often unheralded." Recently, in The New Yorker, the poet-critic Dan Chiasson called Memory "a famous work [that] has been experienced firsthand by relatively few people,"16 which is an effortful way of saying that Memory is not actually a famous work. Relevantly, "Work your ass off to change the language and don't ever get famous" is Mayer's advice to aspiring writers, which first circulated in 1978 (as the final item on a list of writing exercises published by L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E magazine). This line has become one of the most oft-quoted things Mayer has ever written. You'll find it axiomatically cited by public-facing curators, literary journalists, and poetry scholars.17 The frequent reproduction of these words as a slogan by the "relatively few people" who write about Bernadette Mayer has an intricate, cerebral effect: as if Mayer is the opposite of a celebrity, lesser-known for being lesser-known. Perhaps the charisma and wisdom of this oft-quoted advice, its emphatic negative imperative, is rooted in its implicit suggestion — or its intuition — that you are almost famous.

By the time Mayer completed Memory, she felt she was going crazy. Through Ed, she found a psychoanalyst who would see her for free. (He didn't need money because his previous clients included Tuesday Weld and Anthony Perkins, and because Averell Harriman's wife was already paying him $100 an hour.18) "David Rubinfine, psychoanalyst of the stars," Mayer recalled in 2010.19 In his introduction to the 1975 edition of Memory, Rubinfine wrote: "If Bernadette Mayer has any progenitors they are most probably Proust and Joyce. But she is no mere epigone. Her writing is so original that it seems very much like her own invention. But I had better stop here since I realize suddenly that I am so envious that I am struggling with strongly competitive urges. [Signed,] David Rubinfine, M.D."20 The longer this highly credentialed reader looks at Mayer's work, the more his schooled reverence for it gives way to some deep libidinal need for attention and affirmation. But the meaningful question, following Wittgenstein, is about how the work looks back.

***

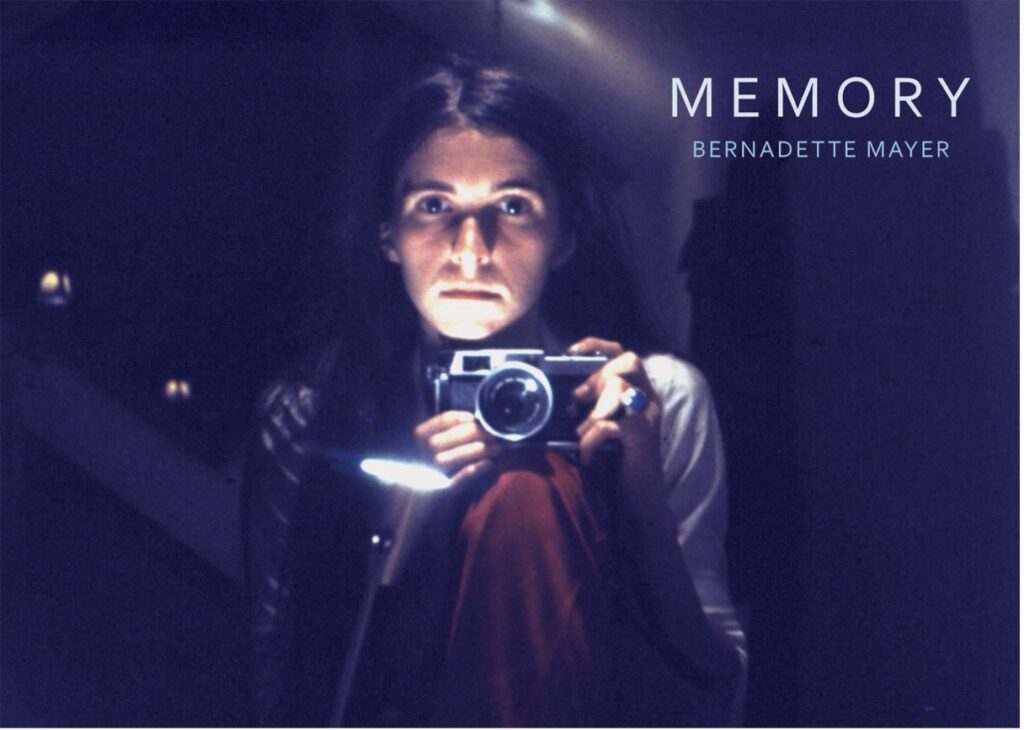

On the evening of July 26th, 1971, toward the end of Memory's experiment, Mayer was watching TV. She snapped a photo of the small blue-gray screen in the corner of the room — on it, the bright small face of an actress in profile — then she got up and went into the bathroom, where she stood in front of the mirror above the sink and took ten dramatically lit photographs of herself. She used a desk lamp to light her face, first from the side, and then from below. Then she stood back and took two artfully composed, symmetrically lit portraits, her head in the center of the frame, her foot resting on the counter and her camera steadied on her knee. (One of these shots became the cover image (fig 1) of the Siglio edition). The corresponding writing for this run of images wrestles with what Mayer calls a "fear of myself in the mirror":

eyes looking at the camera at myself . . . ed asleep & I was determined to catch up with myself by . . . looking in the mirror eight times ten times looking at light, yours mine, the light dimmed on the director's viewfinder whited out over red pants & a white silk shirt . . . the haze on the mirror in a streak of light the bone of my hip & the vein of my forearm . . . the way the light from below on my face makes a triangle, diamond shaped, with my nose at the bottom eyes white & surrounded in my reflection.21

This "determined" writing bounces back and forth in the space between Mayer's body and the surface of the mirror. When she studies the relationship between her image and the camera in her hand, she glimpses someone at work: it is "the director's viewfinder." At this moment, Mayer produces a magnifying, sensuous, breathless catalogue of her features — her clothing, her parts, her shapes, her colors — until she is dizzily "surrounded in her reflection." Then, she bends down and brings her left eye socket to the warm bulb of the lamp, so that the next photograph (fig 2) is of "two eyes just eyes."22

The left eye, wide open, looks up and forward, into the center of the mirror. By a trick of the light, however, the right one appears to glance in a different direction, drifting downward and to the side — toward the camera that peeps surreptitiously above the lower part of the frame. If you look at it a certain wav, Mayer will make a zany23 expression: her eyes, glassy with spent effort, gaze deeply into her own obscure face and away from it at once. "This one's a joke or else the climax," she writes. "I'm exhausted."24

Kathryn Winner is a Ph.D. Candidate in English at Stanford University. She is working on a dissertation called Going Live: Media and Celebrity from the Beats to the New York School.

References

- This essay was written and revised with much needed help from editors Kristin Grogan, David Hobbs, and Dan Sinykin, and my friends Rachel Heise Bolten, Claire Grossman, and Xander Manshel. I must also thank Nina Mamikunian, poetry curator in the Special Collections & Archives at the UC San Diego Library, whose indispensable work and expertise made this research possible.[⤒]

- Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 (Da Capo Press edition 1996; originally published New York: Dutton, 1968), 12.[⤒]

- Her large and enthusiastic audience of readers would eventually make a surprise bestseller out of her first book of collected essays, a writerly, genre-fluid work of critical film memoir called I Lost It at the Movies (1965).[⤒]

- Sarris, American Cinema, 26.[⤒]

- Pauline Kael, "Circles and Squares," Film Quarterly 16, no. 3 (1963): 12-26.[⤒]

- Ibid., 26.[⤒]

- Henri Lefebvre theorized this as the "contradictory character of leisure. As leisure and leisure time become more advanced, leisure's passive modes (movie-going is, for Lefebvre, the epitome of passive leisure) can create or correspond to a desire for more active modes. The idea is simply that we need some regular break from modern professional or family life, however in order to feel personally enriched by our leisure time we might also need to know that we are doing something other or more than just sitting there. See Henri Lefebvre, "Work and Leisure in Everyday Life," from The Everyday Life Reader,edited by Ben Highmore (Routledge: 2002), 228.[⤒]

- The prose in The American Cinema is often so thick with proper nouns it is literally hard to read; on page 28, for example, Sarris lists all sixty directors who once appeared in an 1955 issue of Cahiers simply to demonstrate how long the list is.[⤒]

- Bernadette Mayer and Adam Fitzgerald, "Lives of the Poets: Bernadette Mayer by Adam..." Poetry Foundation: 2010. Henceforward: Interview.[⤒]

- Daniel Kane, "The Live Poet's Society." Ms. Magazine, June 2001, 85.[⤒]

- Ibid 87[⤒]

- Sanders appeared on the cover of LIFE Magazine in 1967 (Feb 17 issue). [⤒]

- Interview.[⤒]

- The Local East Village, "Suze Rotolo and Edie Sedgwick, Slum Goddesses," Blowing Minds 1965 -1972; The East Village Other. [⤒]

- Interview. [⤒]

- Dan Chiasson "Inside Bernadette Mayer's Time Capsule." The New Yorker, Aug. 2020. [⤒]

- Fred Sasaki, art director at the Poetry Foundation, writes, "sometimes I like to compare Bernadette Mayer to Madonna. Of course, an obvious difference lies in Mayer's oft-quoted advice to her students: 'Work your ass off to change the language and don't ever get famous.'" ("Bernadette Mayer's Memory," Poetry Foundation, 2016); after Rae Armantrout won a Pulitzer for Versed (2010), she was asked in an interview: "Language poet Bernadette Mayer advises . . . 'Work your ass off to change the language and don't ever get famous.' Has winning the Pulitzer Prize affected the way you compose your newer material?" (Deborah Escalante and Calvin Pennix, "Don't Back Away: An Interview with..." September 2010). Daniel Kane observes that these words have themselves become "famous" ("'Nor Did I Socialise with Their People': Patti Smith, Rock Heroics and the Poetics of Sociability." Popular Music 31, no. 1 (2012), 119), and uses them as both the title and first sentence of his 2006 edited collection about the second-generation New York School writers, Don't Ever Get Famous.[⤒]

- Interview. [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- David Rubinfine, Introduction to Memory by Bernadette Mayer (Vermont: North Atlantic Books, 1975), 5. [⤒]

- Bernadette Mayer, Memory (New York: Siglio 2020), 276. [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- I'm thinking of Sianne Ngai's well-known explication of the zany as a dominant post-Fordist aesthetic, its "strained, desperate, and precarious" aspect, its unnerving "physical virtuosity," from Our Aesthetic Categories (Harvard University Press: 2012), 10-11.[⤒]

- Memory (Siglio), 276.[⤒]