Decolonize X?

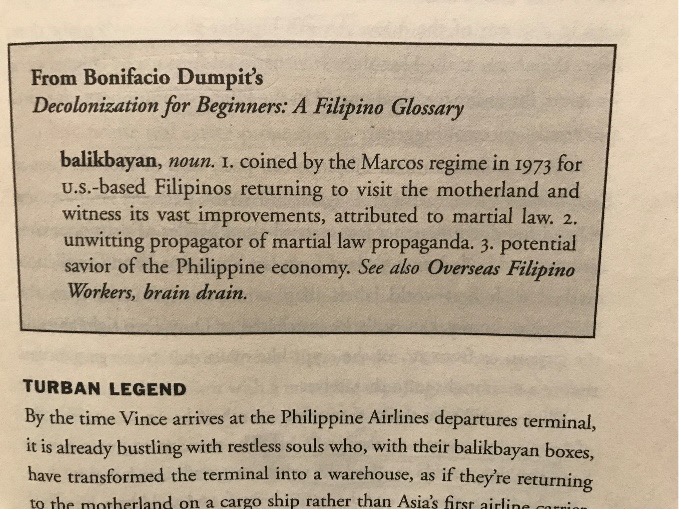

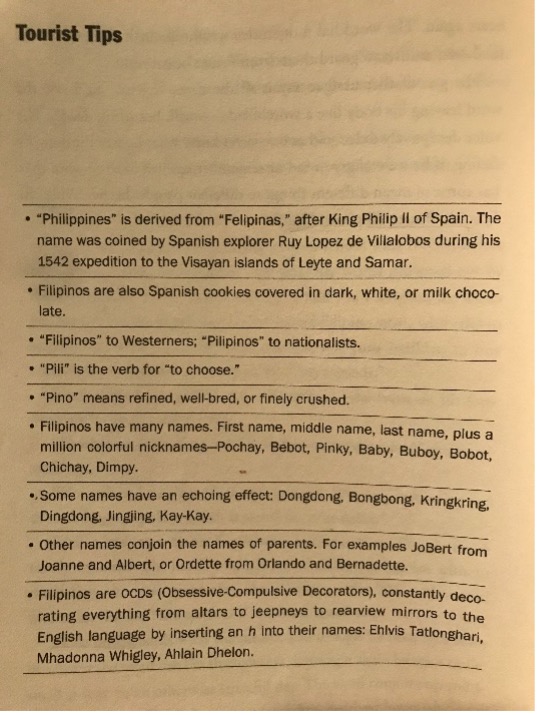

You can't get through R. Zamora Linmark's Leche (2011) without a few detours. Scattered throughout the novelare: selections from Decolonization for Beginners: A Filipino Glossary, a fictive text by Filipino diasporic scholar Bonifacio Dumpit (Fig. 1); and "Tourist Tips" for visitors to the Philippines (Fig. 2). The novel's protagonist is Vicente De Los Reyes (Vince), a queer balikbayan — or "returnee" — who is returning to the Philippines for the first time since he left as a child. The occasion for his return is a vexed one: having placed second in Honolulu's "Mister Pogi" competition, Vince wins a free trip to Manila. (The first-place winner receives a trip to the United States.)

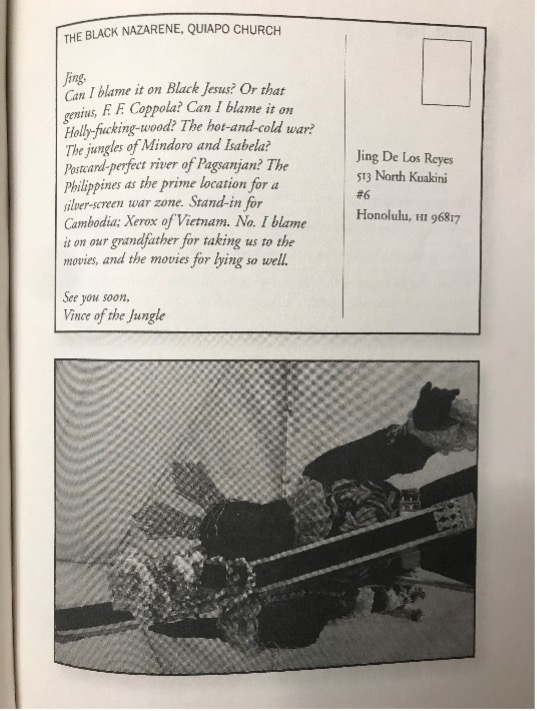

While in Manila, Vince sends postcards to Filipino friends and relatives in Oahu that reveal anxieties around the contradictions of his balikbayan status: that is, a traveler tied to colonial, postcolonial, and neocolonial histories (Fig. 3).1

These contradictions begin in the Manila airport customs line, as Vince struggles to reconcile his understanding of himself as Filipino with his possession of an American passport. When Vince steps into the line for "returning Filipinos," an immigration officer corrects him: "You were a Filipino . . . You're now a balikbayan with a US passport."2 Vince similarly struggles to draw a neat line between balikbayan and tourist as he grapples with the meaning of his visit, particularly now that he no longer has family in the Philippines. Vince's effort to understand the connection between identity and place shapes his subsequent encounters in Manila, especially his erotic attachments to the men he meets as his "guides" — playing on the novel's parodic re-writing of Dante's Inferno. Part of what makes Vince's return journey hellish is that he's caught navigating among competing genres of belonging and the alternative relationships to place that they posit.

Vince's erratic and turbulent trip parallels the manifold routes of Leche's readership, as the novel travels along the complex itinerary of global anglophone fiction. One hallmark of the increasingly globalized contemporary is that the historical forms of colonialism, decolonization, diaspora, and tourism are often entangled in personal histories and popular political consciousness. For example, the cut-and-paste style interruptions of the "Tourist Tips," Decolonization for Beginners snippets, and postcards challenge our assumptions of what it means to be in, of, and from a place; often, as Vince's journey shows, this involves reckoning with complex personal and family histories defined by movement, loss, and silence.

In the attempt to address the complex contemporary manifestations of these historical entanglements and the violences they often entail, one framework has emerged with particular urgency: the call to decolonize. While many novels engage with themes or employ formal devices that resonate with decolonial thought's emphasis on radical structural change, Leche is unusual in that it explicitly features the language of decolonization as one among many possible discursive registers. If the Decolonization for Beginners guide resonates in the novel's parodic key, this is not because Leche is critiquing the politics and history of decolonization per se; rather, the humorous jumps in register signal the novel's attention to the politics of address and the way that geopolitical location shapes how and who and what we hear. Behind Leche's ludic tone is a serious inquiry: who do political critiques claim to speak to and for?

In contemporary discourse, decolonization has come to signify less a historical period — the years after World War II when formerly colonized countries claimed their independence — than a broad aspiration to rectify the structural injustices that have followed from legacies of capitalist colonial exploitation and that continue to shape our present reality. A quick Google search, for example, will turn up attempts to "decolonize travel," "decolonize the museum," "decolonize Thanksgiving," "decolonize your bookshelf," and even — from Lululemon's corporate mission — to "decolonize gender" and resist capitalism. What is clear from these demands to decolonize x is that our social, political, and economic institutions are founded on historical injuries. What is less clear is who is addressed as the subject of decolonization. With the tongue-in-cheek invention of a how-to manual on decolonization, Linmark's novel invites us to consider the mechanics of this ubiquitous call to decolonize. Could such a decolonization beginner's manual exist? Who would it be for? Where does decolonization begin?

Following Dumpit's direct address to "beginners," what would happen if we re-imagined decolonize x,the formulaic imperative the cluster invokes, as x, decolonize, paying attention to the subject implicated in these demands? When we focus exclusively on what needs decolonizing, we participate in a grammatical sleight of hand wherein the sheer force of collective political goodwill shrouds the problem of how individual subjectivity connects to meaningful political collective action. To overlook the part of the imperative that emphasizes the actor, then, misses something crucial about the transformations that decolonization requires and demands. Decolonization, as Frantz Fanon explains, is a historical process, not the "result of magical practices, nor of a natural shock, nor of a friendly understanding." As a historical process aimed at making the world otherwise, it is a "program of complete disorder."3 The disorderly processes that Fanon describes not only re-make colonial institutions and practices, but, just as importantly, they re-make subjects as historical actors. Re-reading decolonize x as x, decolonize pulls back the shroud to make visible our disparate beginning points and emphasizes the transformative work that decolonization requires at the level of subjectivity as well.

Leche shares this emphasis. By making the geopolitical location of the reader a key formal feature, the novel questions the politics of engagement. The generic de-tours through the tourist tips, the decolonization beginner's guide, and the postcards all produce a shifting and unstable second-person address. Leche's continual interruptions "de-tour" the reader away from a fixed destination to linger instead on experiences of place, definitions of arrival, and terms of historical engagement. By reminding us at each and every turn that who we are and where we are shape the meaning of what we do, the novel formalizes the central problems at play when the verb "decolonize" is used as a shorthand for political engagement.

To Gérard Genette's question, "who is speaking?" Linmark adds the important rejoinder, "who is listening, and from where?" In Leche, you are either directly addressed or you're overhearing, and the novel bounces you between the two. In doing so, Leche draws attention to the signs, registers, and genres in which we read ourselves as included or excluded, addressed or overlooked. At times, our exclusion is obvious, as when we read the postcards addressed to another "you," one of Vince's friends or family members. In other moments, however, the mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion are more difficult to pin down — when, for example, "you" are addressed alternately as a tourist, a decolonization beginner, or a balikbayan. Vince, the primary "you" addressed throughout the novel, registers the uncertainty that Leche actively pursues as it places its readers into multiple, sometimes contradictory positions. This unfixed and shifting address is central to how Leche imagines the political work of reading: a process that necessarily, if uneasily, connects the location of the text to that of the reader, the location of the speaker to that of the listener.

In its expansive geographical and historical reach, Leche asks us to read through multiple geopolitical coordinates at once. On Linmark's map, all roads lead to Leche, a palimpsest of colonial, postcolonial, neocolonial, and decolonial histories and practices. Founded in the 1870s by the wives of Spanish government officials as a milk distribution center, Leche was then converted into an orphanage and school for children whose parents were killed in the Philippine-American War. It was later re-purposed by Japanese forces as their main headquarters in World War II. In classrooms are alphabet and grammar charts in Spanish, English, and Japanese — "the languages of the colonial masters."4 From 1965-1986, Leche became a safe house for Ferdinand Marcos's mistresses as he ruled the nation under martial law, and when Vince arrives in 1991, it acts alternately as a sex club, a museum, an archive, and a set for Bina Boca's (a stand-in for Lino Brocka) "turd world" films. Vince — now Vicente, as he introduces himself to the Leche staff — receives not only a "tour" of Leche, but a "De-Tour!" Tita G., Leche's erudite, flamboyant hostess with the mostess who serves as Vicente's de-tour guide, makes clear that a de-tour is not a misstep, but a journey through the silences and "secrets" that mark the paths of official history. To begin mapping the crossed routes of power, desire, identity, and history, the tourist at Leche must become waylaid, wayward, and undone — a "de-tourist."5

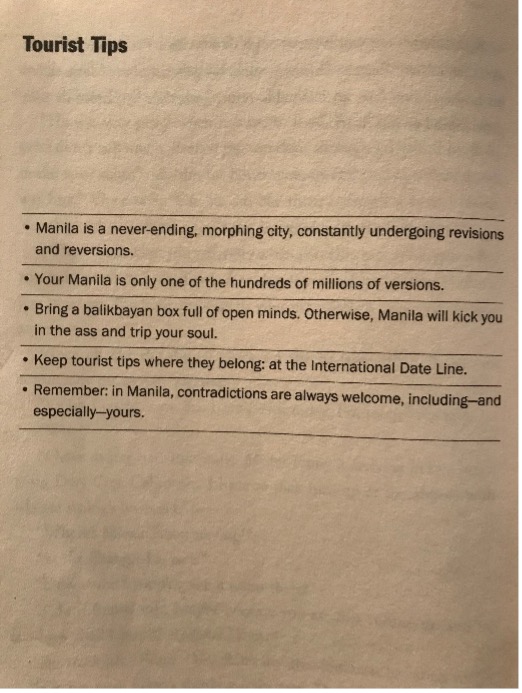

As the novel takes more "de-tours," the "Tourist Tips" become increasingly critical of their own genre, and they start to look more like "anti-tourist tips" (Fig. 4).6

At once anti-tourist tips and anti-tourist tips, the genre collapses under its own historical weight and turns against its implied subject and aim. The "Tourist Tips" and Decolonization for Beginners glossary begin to align to question the logic of "colonial difference" and to interrogate the location of the reader, not the destination.7 Pointing to the legacy of the Philippines's multiple colonizations, the "Tourist Tips" hold a mirror up to tourism's colonial and monolingual paradigms, warning, in English, "Don't use Spanish on them because their Spanish is not your Spanish" (the word "leche" is one such example).8 Similarly, Dumpit explains to the decolonization "beginners": "In Tagalog, there are two words for 'our.' Natin includes you. The other, namin, does not."9 In these vacillations, the novel demands that its readers develop a more sophisticated sense of geopolitical direction, one in which being implicated and being included do not necessarily map neatly onto one another.

Fittingly, the novel's final "Tourist Tips" section ends with the word "yours": "Remember, in Manila, contradictions are always welcome, including — and especially — yours"10 (Fig 4). In this final twist in the journey, Vicente finds himself written into a new script of belonging. But the sense of belonging that the tip conveys is complex in a way that exceeds its own genre. This is not your Manila — à la popular tourist sloganeering — but your contradictions in Manila. This is not the end of the hellish journey, but its beginning: the necessary triangulation of who you are, where you are, and what you carry as your own historical baggage. That yours, therefore, may or may not include you. If the novel has taught us anything, it is that a flat, celebratory inclusivity is not the destination, but just part of the baggage that comes with reading global anglophone fiction across networks defined by imperial and neocolonial power relations. Reading the relationship between yours and ours strikes at the heart of decolonization.

While the novel's "de-tours" are important for the plot and Vicente's character development, they are also helpful for considering the novel's circulation more broadly, acting as a reminder of the need to interrogate the geopolitical dimensions of our objects, our methods, and our own place as readers and critics. To stop our analysis at the recognition that the complex historical entanglements of capitalist colonial modernity have left us all with contradictions would be to miss the need for historical specificity that the "Tourist Tips" and Decolonization for Beginners differently point to. That is, while their genres are theoretically portable, these particular texts are also irreducibly specific to the Philippines. To read that final yours, therefore, means situating yourself in relation to this context specifically — a self-reflexive process that must take place every time decolonization is invoked. As a concept, decolonization may travel, but never in the abstract: it begins with a reckoning with where we — as a "we" — begin.

As the calls to "decolonize x" become ubiquitous, Leche's de-tours remind us to ask: from where are we each beginning, with whom are we in conversation, and in what way are we transformed through political processes and encounters? Our material conditions and subject positions shape the actions available to us and inform the uneven stakes that motivate the desire to "decolonize x." That "decolonize the syllabus" receives, in US institutions, far more traction than calls to engage with ongoing decolonization and demilitarization struggles in stolen and occupied lands under the auspices of the US is a sign of the need to re-route our political aspirations through their historical material stakes.11 To be sure, we need to be critical of our objects of study, and we need to address the supremacies embedded in our canons. But as long as material relations are not changing along with our intellectual paradigms, the work of "decolonizing x" can comfortably exist with the neocolonial and neoliberal logic of soul- and self-making (and, in the Lululemon case, with money-making). The collective subject of decolonization is always in process, negotiating meaning across these worlds of (y)ours.

Kelly Roberts is a writer and PhD student. She lives in Brooklyn.

References

- "From Bonifacio Dumpit's Decolonization for Beginner's a Filipino Glossary:

'balikbayan, noun. 1. Coined by the Marcos regime in 1973 for U.S.-based Filipinos returning to visit the motherland and witness its vast improvements attributed to martial law. 2. Unwitting propagator of martial law propaganda. 3. potential savior of the Philippine economy. See also Overseas Filipino Workers, brain drain.'" (1). R. Zamora Linmark, Leche (Coffee House Press, Minneapolis, 2011).

"Operation Homecoming," as it was called, was established in 1973. L. Joyce Zapanta Mariano explains: "Marcos officially inaugurated the term balikbayan, or 'returnee' . . . Balikbayans were encouraged to visit the Philippines as witnesses to the national and economic development that martial law control could bring to the country" (211). Mariano argues that "the Philippine state, transnational capitalism, and the legacies of American imperialism work in tandem to produce contradictions that arise in diaspora" and notes that these contradictions "are made explicit in Linmark's novels" (211). L. Joyce Zapanta Mariano, "The Intertextuality of Triumphant Diasporic Return: Reading the Novels of R. Zamora Linmark," Filipino American Transnational Activism: Diasporic Politics Among the Second Generation, edited byRobyn M. Rodriguez (Boston: Brill, 2020).[⤒]

- Linmark, 44.[⤒]

- Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, translated by Richard Philcox (New York: Grove, 1961 [2004]). 63.[⤒]

- Linmark, 274.[⤒]

- This idea can also be found in a new nonfictional guidebook to Hawai'i: Hokulani K. Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez's Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).[⤒]

- Christopher B. Patterson, Transitive Cultures: Anglophone Literature of the Transpacific (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2018), 134.[⤒]

- That is, the structures of hierarchical differentiation that emerged as a function of capitalist, colonial modernity. See: Aníbal Quijano, "Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America," Neplanta: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000): 533-580; Walter Mignolo, "The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference," South Atlantic Quarterly 101, no. 1 (2002): 57-96; María Lugones, "Heterosexualism and the Colonial/Modern Gender System," Hypatia 22, no. 1 (2007): 186-209.[⤒]

- Linmark, 120.[⤒]

- Ibid., 250. [⤒]

- Ibid., 316.[⤒]

- Many scholars working within decolonial, indigenous, and critical race paradigms are exceptions here, incorporating practical politics into their intellectual work. For one account of such intellectual-political lineages, see Chela Sandoval's Methodology of the Oppressed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. What becomes more problematic, as Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang spell out, is when the framework of "decolonization" functions as an alibi for maintaining dominant narratives, institutions, disciplines, and identities. See: Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang. "Decolonization is Not a Metaphor." Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1-40. [⤒]