New Literary Television

Misha Green's Lovecraft Country (2020) is a significant moderation of literature and literary forms beyond even its adaptation of Matt Ruff's novel or its explicit references to H.P. Lovecraft. While both are important bases for the series, they are merely two of the numerous literary texts which the series adapts, radically challenges, and revises. While Lovecraft Country acknowledges the importance of literacy, it also acknowledges the dangers of texts, especially white Western texts passively read by African American subjects. Equally important, the show emphasizes active, oppositional reading and takes great pains to illustrate it in practice.

"Getting reacquainted with old friends"?

Lovecraft Country critiques the "whitewashing" of authors and texts, thereby revealing the importance of practicing critical reading. The first episode, "Sundown," identifies the danger of whitewashing when Atticus (Sampson Freeman), picking up Lovecraft's The Outsider and Others, reads from "On the Creation of Niggers." George (Courtney B. Vance), Atticus' uncle, asserts "that's one of Lovecraft's we don't hear mentioned often."1 The exchange points to the ways literary canons selectively suppress discussions of authors' unsavory sociopolitical ideologies, even though their politics inevitably inform the books they write. The suppression of such details leaves readers exposed to ideological violence aimed at them. This problem is especially true in Lovecraft's case, as his numerous personal letters reveal. For example, in a letter from 1934, Lovecraft declared: "Of the complete biological inferiority of the negro there can be no question — he has anatomical features consistently varying from those of other stocks, & always in the direction of the lower primates," concluding "it is wise to discourage all mixtures of sharply differentiated races."2 Additionally, Lovecraft's texts reflect his xenophobia; "Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family" centers around the horrifying discovery that a family's maternal ancestor was a white ape, thereby positioning racial mixing as a point of horror while also maintaining the demeaning notion of Black subhumanity. "The Picture in the House" further develops the anti-miscegenation rhetoric apparent in "Facts Concerning"; the story is so obsessed with racial mixing that even cultural miscegenation becomes a point of terror. Young minority readers unaware of Lovecraft's eugenicist and pro-segregationist ideas unwittingly imbibe notions which insist upon their inferiority, and which contribute to the lived experience of oppression. The series' title and its reading of Lovecraft in an episode which is explicitly about the pervasiveness of Jim Crow violence in America reveal that such canonical suppressions are not just ideologically and culturally destructive to the Black reader, but literally life-threatening.

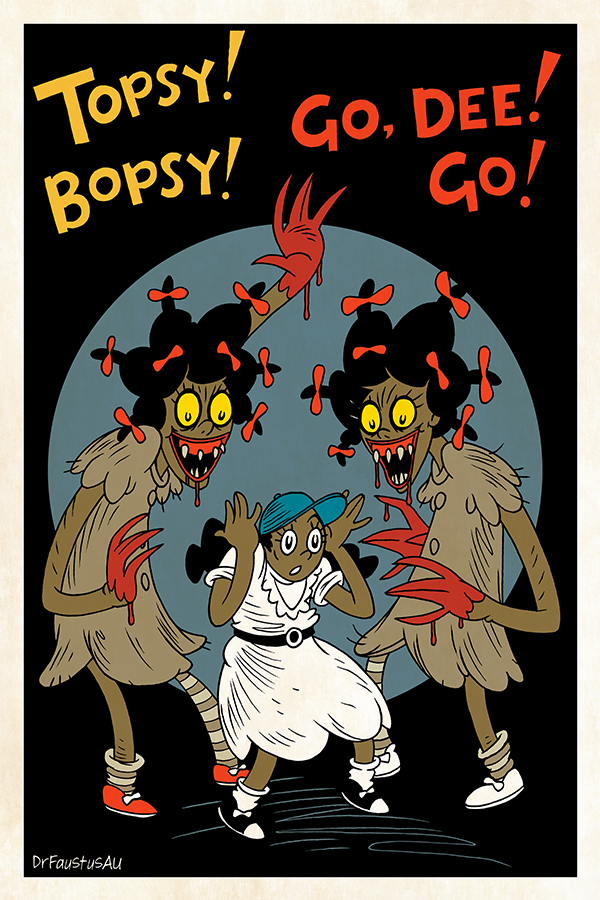

Lovecraft Country shows us how literature, especially that which has been canonized and lauded, can distract us from the real faces and sufferings of marginalized people. Its engagement with texts like Uncle Tom's Cabin and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde argues that literature lies about people through misrepresentations, oversimplifications, and omissions. This is most evident in episode 8, "Jig-a-bobo," which connects Emmett Till's death to Stowe's misrepresentation of Black girlhood. The bulk of the episode follows Dee (Jada Harris) as she is pursued by grotesque versions of Topsy, now doubled as an accompanying Bopsy. Topsy originated in Harriett Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), an abolitionist text which nonetheless produced harmful stereotypes. In Stowe's novel, Topsy "was one of the blackest of her race. [ . . . ] Her mouth [ . . . ] displayed a white and brilliant set of teeth. Her woolly hair braided in sundry tails, which stuck out in every direction. [ . . . ] Altogether, there was something odd and goblin-like about her appearance."3 Topsy is frequently called a "thing" whose eyes "glittered with a kind of wicked drollery" and who sings in "odd guttural sounds [ . . . ] giving a prolonged closing note, as odd and unearthly as that of a steam-whistle".4 Though a minor character, Topsy provides the source of the caricature of the picaninny in minstrel shows and popular culture. Patricia Turner notes that Topsy was a wild child meant to show slavery's evil and corruptive influence. Stage productions eschewed Topsy's tribulations and instead presented her as a mirthful character reveling in her misfortune. Her raggedness became a stock comic feature along with her poor English as she was transformed into a dirty, chicken-stealing "coon."5

Though "Jig-a-bobo" does not depict Till's mutilated body, the episode's depiction of his funeral conjures the horrific images which are made to associate with the grotesque images of Topsy/Bopsy. Topsy/Bopsy and Till's mutilation are equally warped depictions of the Black child body. Such is the insidiousness of canonical texts and their images that even children participate in the violence. As Dee runs from the grotesque specters, she passes white children jumping rope to a nursery rhyme rooted in Black distortion: "Topsy with her yellow eyes, tries to claw the one she spies; follows them from tree to brook, over, under every nook. Topsy has the wildest do, she just wants to dance with you. Jig jig jig . . ."6 Too young to have read Stowe, the children testify to literature's long reach as even they transform Dee, in their rhymes, from a scared and mourning Black girl into a grotesque caricature.

Figs. 1 and 2: Topsy and Bopsy as they appear in the show and as depicted in fan art.7

Part of the transmissibility of literary violence stems from its valorization and replication in popular culture. Such valorization instructs the disdained minority reader — metaphorized as so many different kinds of monsters in the fiction — to accept themselves as detestable and inferior and embrace the racist antagonists that would happily see such readers lynched. Soon after we meet Atticus, the series critiques easy acceptance of racist texts. Describing Edgar Rice Burroughs's A Princess of Mars to an unnamed Black woman, Atticus notes that the hero is a Confederate general:

Woman: He fought for slavery. You don't get to put an "ex" in front of that.

Atticus: Stories are like people. Loving them doesn't make 'em perfect. You just try and cherish them. Overlook their flaws.

Woman: Yeah, but the flaws are still there.8

Atticus's response echoes familiar excuses rationalizing the continued credulous canonization of ideologically destructive texts. The woman's response, however, reiterates the foolishness of attempting to divorce a text from the author's ideals. Furthermore, in choosing to cite A Princess of Mars, Green alludes to how culture uncritically reproduces such texts and their heinous ideals: within the past decade Disney released a film version of the novel under the title John Carter (2012) with no discussion of the text's problematic ideologies.9 Similarly, episode 5, "A Strange Case," points back to Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), a text informed by early eugenics thinking and anxieties over white degeneration in the face of "inferior" populations. The 1931 film adaptation reinforced the story's eugenicist bent by utilizing racist stereotypes of Blacks in its depiction of Hyde.

Learning to Read

Lovecraft Country argues for the necessity of developing and maintaining oppositional reading practices. Premised upon bell hooks' theory of the oppositional gaze in Black Looks (1992) and Stuart Halls' work in "Encoding/Decoding" (1980), oppositional reading, as illustrated by Lovecraft Country, involves applying the critical spectatorship and range of looking relations hooks attributes predominantly to Black women confronted with harmful, stereotypical media depictions of themselves. Black spectators "create alternative texts that are not solely reactions" to problematic "texts"; rather they "contest, resist, revision, interrogate and invent on multiple levels."10 Although hooks and Hall are concerned with film spectatorship, oppositional looking is also useful in engaging white-produced and -centered texts that habitually misrepresent or utterly absent Black people. Dee's comic Orinthya Blue exemplifies the consequence of oppositional reading. A corrective to traditional comics like Superman in which Black women are at best an absent presence, Dee's comics imagine and create an entirely new story for the Black woman reduced to namelessness in traditional comics.

Thus, Lovecraft Country posits oppositional literacy as a liberating force. Atticus argues for oppositional reading as salvation early in the series in an argument with Leti when she deems the language of Adam and the book corrupting. Atticus counters that language and texts are "not inherently evil. It's what we do with it that matters," concluding that learning how to manipulate the text can provide protection.11 Indeed, utterly rejecting Western texts is not the answer, as Hattie warns Leti: "Do not do what Hanna did when she bound the book out of fear. Do not cripple your son with your doubts."12 We encounter liberating oppositional reading by the second episode, when George claims authority for Atticus in the middle of the Sons of Adam dinner by reading and enforcing the bylaws of the society. An otherwise all-white society of elite men, George's navigation and manipulation of their bylaws subverts their racial and economic authority, enabling he and Atticus to command authority over them.13 Thus the series notes the importance of wielding tools such as Western literature, even though literary texts have been one of the methods of dehumanizing and disenfranchising Blacks. As Hanna notes, Western texts and literacy can "be tamed. [ . . . ] This magic was not something to be feared but a gift to pass on."14 The episode "Strange Case" exemplifies oppositional reading multiple times over by writing the Black body into Stevenson's text to counter white racist anxieties and eugenicist ideologies about cultural miscegenation, and by providing a narrative of what actual transformation looks like and means. The episode seems to center primarily on Ruby as the transformative figure who passes undetected as a white woman in the middle of white society and economy. Significantly, Ntozake Shange's "Dark Phrases" (1974) provides the soundtrack to Ruby's second transformation and first exploration of whiteness. The poem expresses the ways Black women's lives are unsung and unheard, pleading for

somebody/anybody

sing a black girl's song

bring her out

to know herself

[ . . . ]

she's been dead so long

closed in silence so long

she doesn't know the sound

of her own voice

her infinite beauty.15

The series features Ruby's singing in "Sundown," as she performs for an engaged and joyous Black community; we never see Ruby sing when she is passing, however. Though passing supposedly provides Ruby unmitigated freedom, in reality her song remains unsung while she wears whiteface. The poem's final refrain — "this is for colored girls who have considered suicide/ but moved to the ends of their own rainbows"16 — arises at the beginning of Shange's choreopoem, not its end. Similarly, the refrain occurs early in Ruby's white explorations, suggesting Ruby's actual transformation has yet to begin and her song yet to be sung. Rather, her passing signifies a kind of suicide, a notion further implied when Christina points out that such physical transformations are always a kind of death.17 As such, the episode rejects Stevenson's eugenics-informed reading of racial transformation, displacing it with a far more subtle but meaningful change: Montrose's cultural transformation.

Montrose's change comments on Ruby's passing defining it a painful, isolated prison, not a pleasant escape. Passing for heterosexual, Montrose suffers extreme self-hatred and consequent rage from having to perform the kind of hypermasculinity which hooks critiques as damning to Black family and love in "Reconstructing Black Masculinity".18 Notably, Montrose has strained relationships with his son and brother, bordering on irretrievably broken in Atticus's case. "Strange Case" reveals the extreme costs of his passing. Fleeing to his lover Sammy after Atticus brutally beats him for killing Yahima,19 Montrose sulks on a sofa, isolating himself as Sammy and friends prepare for a drag ball, playfully bantering and discussing painful details with a kind of levity only possible in the understanding embrace of a safe community. The scenes reveal how passing costs Montrose the comfort and protection of his biological family as well as the support and nurture of queer community, who could serve as a family. Passing only brings pain and isolation, not the joyous freedom Christina promises to Ruby. Indeed, Ruby's passing leads her only to further pain and rage. Montrose, however, achieves true transformation and learns to accept himself — if only briefly — guided by Sammy at the drag ball surrounded by drag queens and kings. As such the episode rewrites what it really means to live life "uninterrupted" as a marginalized subject.

"Now you must learn what was lost"

Lovecraft Country particularly stresses the importance of deploying oppositional reading with history, revealing how historical metanarratives are weaponized against people of color. The series especially addresses the issue early in its plot as Atticus struggles to read Montrose's writing: "the past is something you own... owe..."20 Spoofing on the problem of legibility, the show points to reading and understanding history as something "owned," rather than as something we have a responsibility to, as an error. Navigating history as something owned allows for manipulation of that history, leading to grievous omissions and abuses of the historical subjects. The museum docent in episode 4, "A History of Violence," exemplifies the matter as she explains the origins of the museum's holdings: "In this, one of our museum's oldest sections, we see the many artefacts the famed explorer Titus Braithwhite was given in exchange for teaching the savage tribes the ways of civilized man."21 Alluding to the common misrepresentation of colonial conquest as a "friendly encounter," Green juxtaposes the scene with a discussion between Dee and Hippolyta in which Hippolyta recounts her discovery and naming of a comet, though credit was given to a white child. The juxtaposition directs attention to an obvious untruth in the historical narrative even as Dee and Hippolyta's conversation reminds us of the importance of reading history with an oppositional eye. As the episode's title warns us, History as written and read through a Western lens, is a violence repeatedly done to populations. Such people best navigate the text through oppositional readings which consequently compel them to intervene and yell the truth, as Dee does, so that "now they [all] know it too."22

The show is particularly concerned with correcting the historical narrative around two momentous events: Emmett Till's funeral in 1955 and the Tulsa Massacre of 1921. Historical treatment of Till's death tends to focus on the assailants and on Till's mutilated body, saying little of Till's life, his community or the people who loved him. Consequently, Till is made an isolated object which moves history forward even as he is denied the markers of humanity in life and in death. Similarly, historical coverage of Black reaction to his death focuses upon Civil Rights' deployment of his mutilation, ignoring the trauma and pain of witnessing his mutilated body. Thus, the show intervenes, rewriting the event from a perspective which does not render Till a spectacle. Instead, the episode reintroduces the mourning Black community erased from the historical narrative, writing their trauma and suffering back into the scene of Till's death.

Another significant corrective the series makes is around the 1921 Tulsa Massacre. The event was little discussed in American culture and not at all taught in schools until recent years. Further, the show reminds us how the dominant narrative essentially depopulates Tulsa, reducing the Black victims to an amorphous mass awaiting violence. Instead, the episode presents us with an oppositional reading of that day, detailing the anticipated celebrations and familial exchanges that would have occupied the diverse Black population. The episode culminates in the violence, rather than focusing solely upon it, ending as Montrose provides the clearest intervention into the historical text by narrating the violence from the perspective of the individual. As he watches Tulsa burning, Montrose lists the names of various victims and the actions they took. Episode 9, "Rewind 1921," therefore directs us to the necessity of reading such histories oppositionally and to re-inscribe the historical text with the narratives of the lives lost and the unwritten names of the dead, instead of privileging the violence. Lastly, the show places this violence as one in a number of genocidal assaults in African American experience. We get to Tulsa only after encountering the story of Hiram's brutal experiments on Blacks,23 Titus's brutal theft of indigenous resources,24 Paul's attempted rape of Tamara, among many other violent encounters. As such, Lovecraft Country invites us all to Montrose's project at the end of "Rewind 1921": to reclaim and re-inscribe the lost names in the numerous histories of American violence.

"Magic is ours now"

Connected to the show's emphasis on oppositional reading is its deployment of another kind of "reading": "reading" as a thorough critique of a problematic subject.25 The series accomplishes this "reading" by deploying Black literary texts, thereby reminding us of the generative power of oppositional reading proves. Thus, as mentioned above, the show overlays Shange's "Dark Phrases" above Ruby's transformation to ridicule white terror over Black access to an unchecked sociopolitical economy. More dramatically, as the Sons of Adam attempt to sacrifice Atticus in order to bring about the return of Eden, Gil Scott Heron's lyric poem "Whitey's on the Moon" (1970) plays in the background. The poem critiques white ability and accomplishment, noting that white Americans could manage to put a man on the moon but couldn't or wouldn't face the simpler problems at home, such as systemic racism, poverty and sociopolitical inequality. The series deploys the poem in another era of scientific advancement so great that it seems "magical." In 2018 the company Orion Span announced plans for a luxury hotel in space; 2019 saw SpaceX and Tesla CEO Elon Musk likewise announce plans for a spaceship that will make space tourism possible. The ritual scene thus acts to "read" America once again, pointing out the nation's profound sociopolitical failures as chosen rather than unavoidable.

The series thus reminds us of how Black authors have been generatively "reading" (white) America for generations. We see this clearly in the deployment of Sun-Ra's speech from the album Space is the Place (1973) in the episode "I Am." After Hippolyta has navigated several iterations of herself, she finds herself a heroic space explorer, accompanied by George. Sun-Ra's speech provides the soundtrack for the scene, declaring

I'm not real, I'm just like you. You don't exist in this society. If you did your people wouldn't be seeking equal rights. You're not real, if you were you'd have some status among the nations of the world. So we are both myths. I do not come to you as a reality, I come to you as the myth because that is what black people are: myths.26

Sun-Ra recognizes and appropriates ideologies of Black Otherness and the consequential alienation of African Americans to insist on Black ability and generative power. Although "I Am" does not play the full speech, the series performs the rest of Sun-Ra's text, which concludes "I came from a dream that the black man dreamed long ago. I'm actually a presence sent to you by your ancestors. I'm going to be here until I pick out some of you to take back with me."27 Hippolyta literally embodies the first lines through the lives she navigates, including a 1930s back-up dancer to Josephine Baker and a pre-colonial African warrior. The series, like Sun-Ra, "reads" American culture in these scenes for its determination to write African Americans as powerless victims and historical objects — never subjects — at best. Sun-Ra's text and the scenes thus insist Blacks learn to read history differently, to see white lack in that history and Black generative power in order to create a glorious future. Notably, Sun-Ra does not say all Blacks will come, thereby implying that only those with vision will go with him to this amazing space/ place.

Lastly, Lovecraft Country points to folk texts as vital sources of historical narrative, social critique, philosophy and, ultimately, ways of being which are disdained by dominant white American culture. Nor does the series limit this notion to Black texts; Ji-ah attempts to explain herself to Atticus by reading the Korean story of the kumiho from a folk book. Unfortunately, as an enlisted soldier, Atticus was still too ensnared in Western structures and ideologies to understand that she is speaking about reality, not fantasy. Likewise, Atticus learns of future history through a novel written by his son in the future.28 The book records their family story, thinly veiled as fiction. Given the series' conclusion, the book isn't just a record of familial history but also records how the fate of the world changed. Reading Black texts therefore is a way of fulfilling Hattie's mandate to "learn what was lost."29 In reading (through) Black texts, we learn what has been silenced and erased in history, as well what has been lost spiritually, culturally, psychically, and emotionally as a consequence of existence within a systemically oppressive culture which teaches Blacks a limiting literacy. Only through reading oppositionally can we start to reclaim what has been stolen, critique those that would sacrifice us, and claim power for ourselves.30

Maisha Wester (@maishawester) is Associate Professor in American Studies at Indiana University and a British Academy Global Professor at the University of Sheffield. Her work examines racial representations in horror films, and appropriations of Gothic literary tropes in racial discourses. She is the author of African American Gothic: Screams From Shadowed Places (Palgrave, 2012) and the forthcoming Voodoo Queens and Zombie Lords: Haiti in US Horror Film.

References

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 1,"Sundown," directed by Yann Demange, aired August 16, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- H.P. Lovecraft, The Selected Letters of H.P. Lovecraft, vol. 5, edited by August William Derleth and Donald Wandrei (Sauk City: Arkham House, 1965), 77.[⤒]

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 302.[⤒]

- Ibid., 303.[⤒]

- Patricia A. Turner, Ceramic Uncles and Celluloid Mammies: Black Images and their Influence on Culture (New York: Anchor Books, 1994), 13-14.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 8, "Jig-a-bobo," directed by Misha Green, aired October 4, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- DrFaustusAU, "Topsy! Bopsy! Go, Dee! Go," October 6, 2020, DeviantArt.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 1, "Sundown."[⤒]

- For more on Lovecraft Country's engagement with Burroughs, see Stephen Shapiro, "Un-noveling Lovecraft Country," Post45: Contemporaries, November 2021.[⤒]

- bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2014), 128. Hall's theorization of oppositional reading similarly posits a viewer, or decoder, whose social position is directly oppositional to the imagined audience of a media text. Such a viewer/decoder understands the preferred reading but rejects the text's code, reading it through an alternative ideological code.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 5, "Strange Case," directed by Cheryl Dunye, aired September 13, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 10, "Full Circle," directed by Nelson McCormick, aired October 18, 2020, on HBO. For clarity, Leti is Atticus's friend; she also joins him in the fight against Christina and the Sons of Adam. Hattie is Atticus's maternal ancestor, as is Hanna. Hattie dies in the Tulsa Massacre of 1921; she and Leti meet when Leti is cast back into the past. Hanna is the ancestor who stole the book of names and killed Titus Braithwhite, escaping while pregnant with the child he intended to sacrifice for his ritual. Atticus sees perplexing visions of her throughout the series.[⤒]

- The kind of oppositional reading practiced here can be traced back to figures like Elizabeth Freeman who, hearing the Massachusetts's State Constitution read aloud, argued that it was illegal to hold her as a slave in 1781. Her case led to the abolition of slavery in that state.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 10, "Full Circle."[⤒]

- Ntozake Shange, "Dark Phrases," in For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf (New York: Scribner, 2010), 18.[⤒]

- Ibid., 19.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 5, "Strange Case."[⤒]

- Also in Black Looks: Race and Representation.[⤒]

- Montrose performs violent patriarchy by killing Yahima to protect his family. Green here reminds us of how such "protection" is typically violent, recalling many of hooks' critiques of the performance of Black masculinity.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 1, "Sundown." [⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 4, "A History of Violence," directed by Victoria Mahoney, aired September 6, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 3, "Holy Ghost," directed by Daniel Sackheim, aired August 30, 2020, on HBO. These experiments signify the long history of medical abuses Blacks suffered, from J. Marion Sims gynecological experiments on slave women to the Tuskegee experiments to the "accidental" sterilization of Black welfare recipients; see Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body (New York: Pantheon Books, 1997) for more.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 4, "A History of Violence". Although this assault is contextualized in terms on Indo-Americans, it also points back to the thefts suffered by other people of color in the midst of colonial conquest.[⤒]

- I refer to the slang usage of "reading" originating in queer culture. To "read" means to openly critique someone, often publicly and sometimes with added exaggeration. The practice is typically attributed to Black drag queens but has been popularized beyond that community. See Patrick E. Johnson, "Snap! Culture: A Different Kind of 'Reading,'" Text and Performance Quarterly 15, no. 2 (1995): 122-42; Paul Baker. Fantabulosa: A Dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang (London and New York: Continuum, 2004); Gary Hartley, "A Beginner's Guide to Drag Terminology," Capetown Magazine, accessed October 19, 2021.[⤒]

- Sun-Ra, Space is the Place, Blue Thumb Records, 1973. Sun-Ra's ideas and artistry spawned two important fields: Afrofuturism and Afrospeculative art.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Thrown into the future by an accident, Atticus receives the book from future Dee.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 9, "Rewind Tulsa 1921," directed by Jeffrey Nachmanoff, aired October 11, 2020.[⤒]

- The series warns against placing too much weight and power on texts alone; as the group goes into battle, Dee reads: "He knew telling a story was a kind of power, but he also knew it wasn't enough. If they were going to truly disrupt the hierarchy of warlocks, they would have to spill blood other than their own." Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 10, "Full Circle."[⤒]