New Literary Television

Chapter 4 of Jason Mittell's 2015 book Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television, on "Characters," begins: "Nearly every successful television writer will point to character as the focal point of their creative process and how they measure success — if you can create compelling characters, then engaging scenarios and storylines will likely follow suit." 1 Yet, in the early period of prestige television dominated by The Sopranos (1999-2007) and The Wire (2002-2008), it became a cliché to associate this phenomenon with a revival of the social taxonomies of the big nineteenth-century novel. As Mittell's discussion of prestige characters suggests, however, this is a false opposition. Prestige dramas are dominated, Mittell contends, by one type of character in particular, the male antihero who "is our primary point of ongoing narrative alignment but whose behavior and beliefs provoke ambiguous, conflicted, or negative moral allegiance," 2 and whose charisma "create[s] a sense of charm and verve that makes the time spent with [him] enjoyable, despite [his] moral shortcomings and unpleasant behaviors."3 Thus The Sopranos is deeply concerned with the "personal history that shaped [Tony's] amorality, his moral quandaries, and the anxiety attacks that derive from his internal conflicts,"4 while Breaking Bad's (2008-2013) "complex characterization" of its protagonist Walter White "invites [the viewer] to examine what makes him tick, how he is put together, and where he might be going, while at the same time emotionally sweeping [them] up into his life and string of questionable decisions."5

Shows like The Sopranos and Breaking Bad, that is to say, are deeply concerned with subjectivity, and if they bear comparison with nineteenth-century realism it is not — or not only — because of their social taxonomies, but, in Lukácsian terms, for the way they aspire towards a "concrete potentiality [ . . . ] concerned with the dialectic between the individual's subjectivity and objective reality."6 For Lukács, realists offer "a description of actual persons inhabiting a palpable, identifiable world" while even a great modernist like James Joyce gives us a Dublin that, however "lovingly depict[ed]," remains "little more than a backcloth" to the treatment of "the realm of subjectivity."7 At their best, The Sopranos' North Jersey, The Wire's Baltimore, and Breaking Bad's Albuquerque all achieve this level of dialectical interrelationship with the shows' respective characters.

Yet bearing in mind the definitionally anti-social nature of the antihero, and his centrality not only to these shows but to the first wave of prestige television in general — Mittell cites, among other examples, The Shield's (2002-2008) Vic Mackey, Dexter's (2006-2013) Dexter Morgan, and Mad Men's (2007-2015) Don Draper — we might be forgiven if we begin to see the concern with complex characterization as a paradoxically mechanical device across the range of these shows. Yes, they tell us again and again, people (or, for the most part, men) are complex creatures with a strange blend of positive and negative traits. In the aggregate, that is to say, prestige television's antiheroes, so far from offering a return to the social world of realism, in fact reflect Lukacs' critique of modernism as divorcing subjectivity from the social world, and giving us man as "an ahistorical being."8 Consider here another quote from Mittell, generally a very careful describer of texts: "Some antiheroes stretch a rebellious member of a typically upright organization to its moral limits, as with The Shield's portrayal of rogue cops turned into corrupt murderers and thieves."9 If this sentence functions as a form of what we call "copaganda," insisting that we see The Shield not as a show about a corrupt institution, but about corrupt members of a generally good institution, this is not just because that formulation is so present in contemporary accounts of the police. It is also because the form of the antihero leads us to it almost mathematically. The antihero is the man in conflict with his environment, and therefore the antiheroic criminal has surprisingly good qualities, the antiheroic cop surprisingly bad ones.

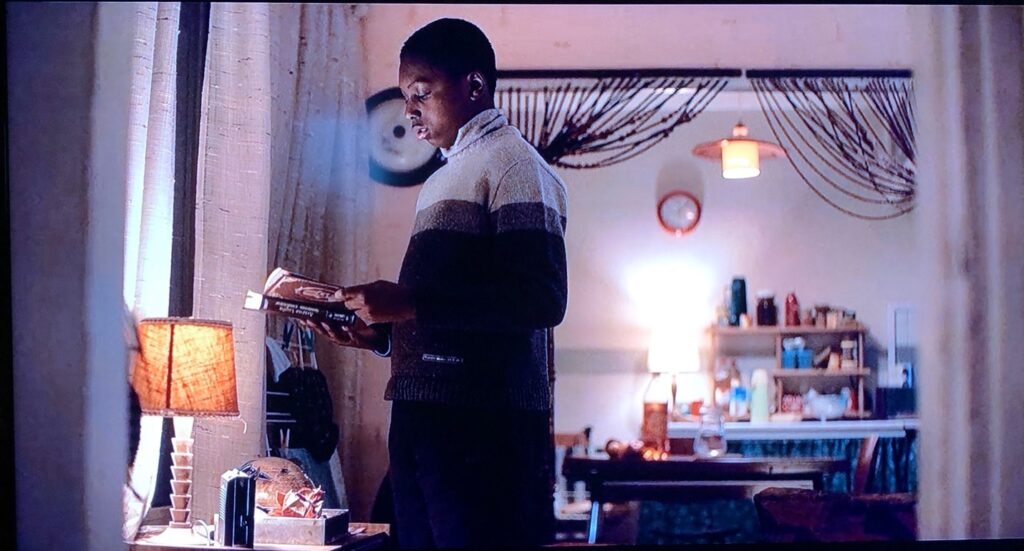

One of the refreshing pleasures of George Kay and François Uzan's French-language Netflix series Lupin is its almost complete disregard of this US prestige television formula. Kay and Uzan's show debuted on the streaming service on January 15, 2021, and according to Netflix's own rating system (based on the number of people who watched two minutes or more of the show) became the service's biggest international hit, poised to reach 70 million viewers in its first 28 days and surpass even the robust numbers for the Shonda Rhimes-fronted Bridgerton.10 The series centers on Assane Diop, the son of a Senegalese immigrant whose father was framed for a theft by the patriarch of a wealthy French family whom he served as a driver, subsequently committing suicide in prison — or so it seems, although a hallmark of the series is that events are never quite what they appear to be at first. In any case, before the elder Diop died he gave his son a volume of French writer Maurice Leblanc's early-twentieth century stories about the master criminal Arsène Lupin (Figure 1). The boy — first shuttled to an orphanage and then sent to a prestigious private school as a charity student — took his near-namesake's adventures as a guide to life, becoming himself a master thief bent on revenge against the man he believes responsible for his father's death.

On the surface, Lupin's protagonist might seem like a textbook example of the antihero. As played by French sketch comic and actor Omar Sy, he is both charismatic as hell and morally ambiguous, an unrepentant criminal with an estranged wife and questionable parenting skills. But Lupin in fact wears its protagonist's character flaws, like its frequent flashbacks to his younger days, lightly. The series is in no way organized, as Mittell says of Breaking Bad, around a long arc designed to explore "what makes [the protagonist] tick, how he is put together, and where he might be going."11 Assane's amorality is not a problem for the series, but rather a precondition: the circumstance that lets us enjoy the true pleasure of the series, which is, just as in Leblanc's stories, reveling in the protagonist's mastery.

What this means, I'd like to suggest, is that Kay and Uzan's series is extremely literary without being in the least bit prestigious. Lupin is literary in multiple senses. First, it is literary in its relationship to its source material, which is one not of revision but of adaptation. Like Ladj Ly's 2019 film Les Misérables, which has a character mention Victor Hugo's 1862 historical novel but otherwise departs from it to tell a new story of crime and punishment in a banlieue populated mostly by Muslim immigrants, Lupin loosely updates its source material in the context of a twenty-first-century France shaped by the in-migration of non-white inhabitants of the nation's former colonies. But second, and unlike Ly's movie, the series is literary in the sense that it is directly engaged with representing readers of fiction — Assane first and foremost, of course, although he also passes Leblanc's stories on to his own son, and the first series culminates in a December 11 trip to Étretat for a festival celebrating Leblanc's birthday and populated by numerous attendees dressed as Lupin.

Lupin's specific forms of literariness, that is to say, raise questions about 1) what constitutes literature and 2) how readers use it. In doing so, it departs significantly from the more conventional assumptions of US prestige television: briefly, that literature offers its readers representations of complex human psychology, and perhaps of its interaction with social forces. In part, this is because Lupin arises from a different nineteenth-century literary tradition, one concerned primarily not with individuals or their social worlds but rather with, to be usefully reductive, events. This literary tradition, epitomized by Hugo, finds its complexity not in human psyches but in plots — in the dual sense both of secret plans and of narratives.

Lupin's first episode nods to this lineage, with Assane successfully stealing an artifact called "The Queen's Necklace" from the Louvre. This is an allusion to a real story from the final days of the Ancien Régime, one that is almost impossible to summarize with any concision. In 1772 Louis XV commissions a necklace from the French jewelers Charles Auguste Boehmer and Paul Bassenge for Madame du Barry, then dies of smallpox before it is finished. His successor Louis XVI offers it to his queen Marie Antoinette, who turns it down. Later, a confidence woman named Jeanne de la Motte feigns a relationship with the Queen to extract money from her lover the Cardinal de Rohan, who had fallen out of favor with Marie and was attempting to win his way back into the court. Boehmer and Bassenge approach de la Motte to assist them in selling the still unpurchased necklace to Marie, and de la Motte instead convinces the Cardinal to buy it on the Queen's behalf — only to have him give it to a man who, working with de la Motte, dismantles it and sells the gems. This story reinforced public perceptions of Marie Antoinette and the royal family in general as frivolous and given to scandal, in some accounts helping to bring on the Revolution. If all this sounds like an Alexandre Dumas plot, it in fact became one, in his 1850 novel The Queen's Necklace — although Dumas, apparently not finding the story quite Byzantine enough, creates an elaborate role for the Italian occultist and adventurer Alessandro di Cagliostro as the puppet master manipulating events behind the scenes.

Both Leblanc and Kay/Uzan draw upon these events for their versions of Lupin. Leblanc's story "The Queen's Necklace" addresses the historical Affaire du collier de la reine in about a paragraph and a half, then invents a conclusion in which the necklace is reconstituted with less valuable diamonds and passed down within the Dreux-Soubise family to the present day, when it is stolen from a locked room in which the embarrassed aristocrats keep it. Suspicion falls upon Henriette, a poor friend from Mme. Dreux-Soubise's convent days who serves her as an unofficial maid and dressmaker in exchange for a small room for herself and her son. Mme. Dreux-Soubise puts Henriette out, and is subsequently surprised to receive a letter from her erstwhile maid thanking her for monthly gifts of money. But although the police investigate the matter it remains a mystery until years later, when a party guest — "the Cavaliere Floriani, whom the count had met in Sicily" — pretends to solve the mystery but in reality relates his own role in it: he is Henriette's son, whose successful theft of the necklace starts him on his career as none other than Lupin.12 The necklace that Assane Diop steals in the first episode of Lupin, meanwhile, belongs to the Pelligrini family, who has recovered it after its putative theft years before — the theft for which Hubert Pelligrini (Hervé Pierre) had framed Assane's father, setting Assane on his own path to becoming a master thief.

Both Leblanc and Kay/Uzan's versions of Lupin are far more interested in plot than in character, in events than in psychology. Assane's complicated relationship with his ex-wife and son might provide, in US prestige television, the basis for exploring the complexities of his character — as Walter White's relationship with his wife and son do, for instance, in Breaking Bad — but every time Kay and Uzan's series approaches this possibility it quickly sets it aside for plot. After seeming to neglect his son Raoul's (Etan Simon) birthday, for instance, Assane gives him a trip to Étretat for a celebration of Leblanc's birthday on the same day (Figure 2) — a circumstance that might in another show lead to an exploration of Assane's inability to see his son separately from his quest for vengeance, but here sets up Raoul's kidnapping as the cliffhanger which ends the show's first series.

Indeed, one might go further and note that both Leblanc and Kay/Uzan's versions of Lupin depend upon plot formulas that they repeatedly satisfy. For Leblanc, this is the endlessly repeated revelation that Lupin has been someone else in the story all along, even the narrator. Kay and Uzan's series gestures toward this in its opening episode, in which we first encounter Assane as a cleaner in the Louvre, then see him going to a loan shark to whom he owes money, and who at one point has his muscle hang Assane from the balcony of his HLM. It is only when Assane subsequently overpowers the henchman and offers to repay the loan shark by bringing him into a heist at the Louvre that we begin to realize who he is. Of course, it would be impossible to sustain this twist in a visual medium, but Kay and Lupin's series replaces this formula with a different one, the pleasure of seeing Assane's apparent failures turn out to be merely parts of complicated schemes that he has himself engineered. Thus, he is not a poor worker at the mercy of a loan shark but an intriguer manipulating the small-time criminal for his own ends. And thus, when Assane's plan seems to fall apart and the loan shark and his henchmen are captured with the Queen's Necklace, we discover that they are in fact carrying a fake that Assane has slipped them so that their capture can serve as a distraction for Assane, in another disguise, to walk out of the Louvre with the real thing.

Assane is, that is to say, a master of the Batman Gambit, which the website TV Tropes defines as "a plan that revolves entirely around people doing exactly what you'd expect them to do."13 Again, this is a repeated feature of the show — in the second episode, for instance, Assane gets himself locked up in prison with a man who has information about his father, then gets to the man in the prison infirmary by manipulating a prison don into having him stabbed. As TV Tropes further notes, Batman Gambits depend on others acting in character, and so "are only as successful as their planner is knowledgeable and insightful about those involved."14 All of which is to say, perhaps, that Lupin doesn't care about Assane's psychology because it is positioned at another level where Assane is the one who knows about others' psychology — and does so not for the pleasure of insight but because this knowledge makes things happen. One way to put this is to say that if he has arrived at his vocation by being a reader, the vocation itself is in fact (as it often is for ardent readers) that of a writer.

What Lupin is knowledgeable about of course includes the workings of racism within French society. This is evident, for instance, in the plot he uses to break into prison to speak to his father's old cellmate Comet (François Creton). He enters the prison as the visiting cousin of another inmate, Djibril Traoré (Athaya Mokonzi), who despite being of African descent — albeit, to go by his name, Manding rather than Wolof — is a good foot shorter than Assane and otherwise looks nothing like him. When Assane tells Traoré, "Your cousin has a present for you. You [ . . . ] get out. I go inside instead," Traoré laughs and replies, "Oh I know actually. [ . . . ] The guards won't notice anything because you and I totally look like twins.15 Assane — whose watch timer has just gone off — explains that the guard who brought Traoré in is going off duty, and the other prisoners won't notice anything because Traoré has been quarantined for the last week and is only now being sent to a cell. Clearly this plan relies upon, and within the context of the show makes sport of, the idea that all Africans are interchangeable not only for non-African-descended French people but (a joke at Foucault's expense here?) for carceral institutions as well. The script offers a fig leaf for Assane's actions when he tells Traoré "I know why you're here. Deal so much as a joint, I'll find you" — Assane will assume the role of the police if Traoré relapses — but in fact the point here is an amoral view of systems of power which sees them as obstacles to be navigated, and in the process reveals their structural workings.16

What's important to stress here, however, is that what's compelling about Lupin is not this or any other content per se, but rather the form in which it places this content. Again, the form of US prestige TV, at least in its first incarnation lasting up until around 2015, is one that, like the psychological realism that dominated Anglo-American fiction for most of the twentieth-century, privileges character depth and complexity. This is a form that has the potential, early on identified by Lukács, of short-circuiting the connection between individual and society, and making the latter merely a "backcloth." Both Leblanc and Kay/Uzan's version of Lupin, by contrast, are radically depsychologizing — in part because they circulate in the realm of "mere" entertainment. But this shouldn't blind us to something potentially larger going on within the form.17

Here it's worth noting that one of Leblanc's models for his original Lupin was the French thief and anarchist Marius Jacob. In the early twentieth century Jacob organized a gang called "the Workers of the Night" whose members lived according to the following principles: no killing, except in the protection of one's life or one's freedom from police; theft only from the parasitic classes (bosses, judges, soldiers, clergy); a percentage of the takings reinvested in contributions to the anarchist clause.18 Lupin's original, that is, is a criminal with a code — not an individual code of honor, but a social counter-logic. Jacob was, in the words of the subtitle of William Caruchet's 1993 biography, un anarchiste-cambrioleur.19

This influence survives in Leblanc's version of "The Queen's Necklace" to the extent that it is a story not only about class resentment but, more importantly, about a form of action taken against one's class enemies. This flickers briefly in Leblanc's description of Floreani/Lupin as he pretends to "solve" the mystery of the necklace's disappearance: "There was something resembling irony — an irony, moreover, that seemed hostile rather than sympathetic and friendly, as it ought to have been."20 This is not to say that Leblanc was writing anarchist fiction: on the contrary, at the conclusion of "The Queen's Necklace" Lupin restores the titular object "to its lawful owners."21 What's arguably more important, however, is how the hostile irony in Floreani/Lupin's demeanor transmutes itself along the way. As Leblanc writes at the conclusion of Floreani/Lupin's monologue:

How extraordinary must be the existence of this adventurer [ . . . ] who [ . . . ] with the refined taste of a dilettante in search of an emotion, or at most, to satisfy a sense of revenge, had come to brave his victim in that victim's own house, audaciously, madly, and yet with all the good-breeding of a man of the world on a visit!22

The "or at most" is, as they say, doing a lot of work here. What's central in this description, and I would argue in Leblanc's Lupin stories as such, is the way in which Leblanc treats class anger not as a subject for psychological investigation — no Dostoevsky here — but as something that is transmuted in the character's life into a set of forms (manners, criminal plots) that take on an instrumental function as weapons.

If Leblanc's language of "a dilettante in search of an emotion" invokes existentialism, that is to say, it is not the existentialism that (particularly in its American translation) upholds a kind of dehistoricized individualism, but rather the existentialism that undergirds Jean-Paul Sartre's 1961 preface to Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth. Of course, it might seem strange to associate the psychoanalyst Fanon with a rejection of psychology, but as Sartre aptly notes, Fanon was not at all interested in the psychology of colonizers. Praising Fanon as a kind of physician who describes the colonies as a disease, Sartre writes, "Of course, Fanon mentions in passing our well-known crimes: Sétif, Hanoi, Madagascar: but he does not waste his time in condemning them; he uses them. If he demonstrates the tactics of colonialism, the complex play of relations which unite and oppose the colonists to the people of the mother country, it is for his brothers; his aim is to teach them to beat us at our own game."23

Here we arrive at an apt description of Kay and Leblanc's Assane Diop — a keen analyst of his enemies whose goal is to "beat [them] at their own game" — by way of a detour through the French colonial circumstances that drive the character in addition to (or complication of) the class anger present in Leblanc's Lupin. Crucially, Assane's charisma is not a separate quality that reconciles us to his faults. Rather, it derives fairly uncomplicatedly from our investment in his success, despite the fact that he routinely breaks laws. And this is the case because of the particular version of French literary amoralism that it draws on — not one that believes all is permitted, but rather one that takes for granted that all institutions (the police, education, philanthropy) are corrupt and organized for the benefit of those with wealth and power. The show introduces a corrupt police commissioner, Gabriel Dumont (Vincent Garranger / Johann Dionnet), not to mine his psychological complexity, but rather to show his role in a set of social arrangements ultimately controlled by Hubert Pelligrini, the billionaire who framed Assane's father. And while near the end of Series Two both Dumont and Pellegrini are arrested, we last see Pelligrini smiling enigmatically in a way that suggests he may not suffer the same consequences as his erstwhile operative. Moreover, the series ends with Assane himself on the run from police.

Of course we don't know where the show will go in Series Three, but I would argue that this development at least provisionally reverses the restoration of social order that occurs at the end of Leblanc's "The Queen's Necklace." Rather than having the master thief restore the rightful property of the aristocracy, Series Two refuses to resolve things and hints that there are larger forces which will forever confer immunity upon Hubert and liability upon Assane. Or maybe this is all just the set-up for the show's true imperative, the ongoing plot. What I hope I've suggested, though, is that this imperative is itself on some level doing the serious work of reorienting its viewers into a social vision not governed by liberalism's fatalism and fetish for complexity. Maybe, Lupin teaches us, some things and people are just bad, and need to be not understood but fought—over and over and over.

Andrew Hoberek is Professor of English and Interim Chair of the School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at the University of Missouri. He is currently working on a book project tentatively titled Stand by Your Man: Tammy Wynette and the Other 1968.

References

- Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 118.[⤒]

- Mittell, Complex TV, 143.[⤒]

- Mittell, Complex TV, 145.[⤒]

- Mittell, Complex TV, 144.[⤒]

- Mittell, Complex TV, 164.[⤒]

- Georg Lukács, "The Ideology of Modernism," in The Meaning of Contemporary Realism, translated by John and Necke Mander (London: Merlin Press, 1962), 24.[⤒]

- Lukács, "The Ideology," 24, 21, 23-24.[⤒]

- Lukács, "The Ideology," 21.[⤒]

- Mittell, 143.[⤒]

- Manori Ravindran, "'Lupin' Will Be Seen by 70 Million Subscribers, Netflix Claims," Variety, January 19, 2021.[⤒]

- Mittell, 164.[⤒]

- Maurice Leblanc, Arsène Lupin, Gentleman-Thief (New York: Penguin, 2007), 82.[⤒]

- "Batman Gambit," TV Tropes, accessed October 12, 2021.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Lupin, season 1, episode 2, "Chapter 2 - L'Illusion," directed by Louis Leterrier, aired January 8, 2021, on Netflix.[⤒]

- Lupin, season 1, episode 2, "Chapter 2 - L'Illusion."[⤒]

- In his piece for this cluster, Stephen Shapiro, writing on HBO's 2020 series Lovecraft Country, compellingly argues that around 2008/2011 prestige television shifts away from its commitment to the liberal principles of the serious novel and finds in genre fiction a more expansive vision of sociality grounded in the collective organizing of people of color and others previously excluded by the liberal consensus. While I cite 2015 as my end date here, primarily because it's when Mad Men — the last of the great antihero shows — concludes, I think the success of Lupin clearly has something to do with a transition of the sort that Shapiro describes. Stephen Shapiro, "Un-noveling Lovecraft Country," Post45: Contemporaries, November 2021.[⤒]

- Michael Loadenthal, The Politics of Attack: Communiques and Insurrectionary Violence (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 48.[⤒]

- William Caruchet, Marius Jacob l'anarchiste cambrioleur (Paris: Séguier, 1993).[⤒]

- Leblanc, 87-88.[⤒]

- Leblanc, 91.[⤒]

- Leblanc, 89-90.[⤒]

- Jean-Paul Sartre, preface to The Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon, translated by Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1963). I prefer this translation to Richard Philcox's in the 2004 Grove Press edition of Fanon's book because it ends with "beat us at our own game" rather than the less descriptive "outwit us." Jean-Paul Sartre, preface to The Wretched of the Earth, by Franz Fanon, translated by Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004), xlvi. [⤒]