New Literary Television

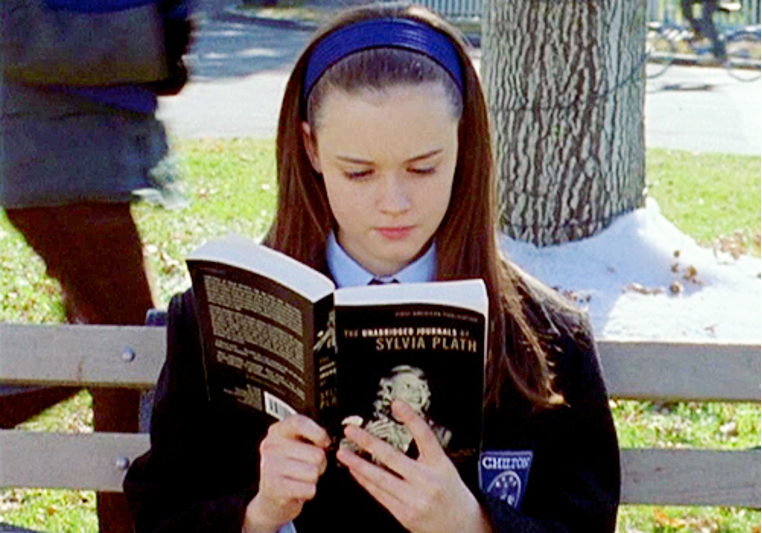

Perhaps no image is more representative of the young Rory Gilmore (Alexis Bledel) — protagonist, along with her mother Lorelai Gilmore (Lauren Graham), of the TV series Gilmore Girls (2000-2007), created by Amy Sherman-Palladino — than her reading a book, so completely absorbed in a literary classic that she's blissfully unaware of everything else. This is how her passion for literature is first introduced in the show's pilot, when the new heart-throb in town and soon Rory's first love interest, Dean (Jared Padalecki), admits he has fallen for her when watching her reading Moby Dick with "unbelievable concentration," while a drama, complete with blood gushing and an ambulance, unfolds around her. "I thought," Dean confesses, "I have never seen anyone read so intensely before in my entire life. I have to meet that girl."1

Rory is frequently hailed as one of the most well-read characters in TV and a role-model for bookworms everywhere.2 She even spawned the "Rory Gilmore Reading Challenge," accompanied by book clubs both online and offline, which challenges people to read every single one of the 339 books mentioned in the series — a number updated to 408 after its revival, Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life, aired in 2016.3 Writing about Gilmore-isms, the show's hallmark fast-paced dialogues, where we find many of the intertextual references to literary and popular culture that constitute the reading challenge, Justin Owen Rawlins argues that these dialogues align the series with prestige TV.4 But literary references do not just serve to signal the show's cultural capital or explore cultural capital's very nature. Rather, the world of literature and books is integral to how Rory understands herself and, therefore, arguably helps illuminate the imperatives and shortcomings that characterize her as a neoliberal "achievement-subject." This is a subject defined by philosopher Byung-Chul Han as one driven by the "paradigm of achievement, or, in other words, by the positive scheme of Can."5

"I live in two worlds", Rory proudly proclaims at her prep school graduation speech. "One is a world of books. I've been a resident of Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County, hunted the white whale aboard the Pequod, fought alongside Napoleon, sailed a raft with Huck and Jim, committed absurdities with Ignatius J. Reilly, rode a sad train with Anna Karenina and strolled down Swann's Way."6 The image of living in two worlds, together with the iconic scenes of Rory's absorbed reading, seem to suggest a certain degree of separation between the world of literature and books and the "real" world, as well as Rory's desire to retreat from the latter world into the former. Yet Rory's love for literature is also very much intertwined with real-world ambition and aspiration. Lorelai, Rory explains in her speech, "filled our house with love and fun and books and music, unflagging in her efforts to give me role models from Jane Austen to Eudora Welty to Patti Smith" and "never g[iving] me any idea that I couldn't do whatever I wanted to do or be whomever I wanted to be." Here, literature and literary culture are framed as the fuel of Rory's "Unlimited Can", which, Han maintains, "is the positive modal verb of achievement society".7 And, hardly surprisingly, the fire of Rory's "Unlimited Can" is stoked by Lorelai, whose own neoliberal subjectivity is defined by her "cheery, ceaseless entrepreneurial drive".8

We know Rory's aspirations right from the show's start: to be like CNN journalist Christiane Amanpour and "travel, see the world up close, report on what's really going on, be part of something big".9 Except for a blip in season 6 when she drops out of university, Rory sails through the markers of a young person's individual and academic success, or at least the "narrowly defined, elitist notion of education" the show embraces, on her way to achieving these aspirations.10 She is the year's valedictorian at the prestigious Chilton's prep school, goes on to be accepted to the country's top institutions, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale (she chooses to study journalism at Yale), and is the editor of the distinguished Yale Daily News. Of course, none of this would have been possible without the Gilmore family's money, which pays for the considerable expense of Rory's private education. Yet the show's emphasis is always on Rory's extraordinary abilities, her dedication, work ethic, and drive, rather than on the privileges, including her whiteness, that make the nurturing of these qualities possible in the first place.

As Anna Viola Sborgi argues, we can map Rory's character development, as well as her academic/professional development, onto her readings. These move from the novels by women writers which Rory reads in Gilmore Girls's first seasons and which "portray strong-willed, witty, and independent women in the process of fashioning their own identity [ . . . ] echoing Rory's own struggles in 'writing' her own life narrative," to the political editorials and hard-boiled journalism of later seasons, when her career ambitions solidify around the world of journalism.11 The show's end represents the culmination of Rory's reading experiences and writing aspirations, as Rory becomes a reporter on the Obama campaign straight out of Yale. Crucially, Amanpour has a cameo in Gilmore Girls's finale, sanctioning the achievement of the aspirations Rory confided back at the show's start.12 Gilmore Girls thus closes celebrating achievement — significantly, Rory reports on a campaign whose slogan ("Yes, we can") can be seen as epitomizing achievement society — and on the promise of a brilliant writing career ahead of Rory.13

Nine years later, A Year in the Life find this promise flagging. A publicity stunt from a few months before the revival's release tries to take us back to the Rory we left in Gilmore Girls. We see her marching into the White House, confident and accomplished, accompanied by stacks of books and ready to advise Michelle Obama on her reading. Clearly, the short video implies, Rory still has an in with the Obamas.14 What A Year in the Life eventually shows us is, however, very different. Rory's main success story since we left her seems to be a New Yorker "Talk of the Town" piece, whose singularity is comically emphasized by virtue of its replication in the many copies of the article accumulated by "super-proud" Luke (Scott Gordon Patterson), Lorelai's partner: boxes upon boxes of the magazine, as well as his diner's menus sporting the piece on their backs.15 Where in Gilmore Girls Rory represented the potential of the achievement-subject, in A Year in the Life she represents this subject's failure, which left many viewers, who looked up to her and identified with her, feeling cheated by Rory's fate in the revival.16

![An older Rory reads her New Yorker essay from a menu in a diner. The subtitles read: "That's my piece. [in Southern accent] Wrapped in plastic."](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/cristofaro_3.png)

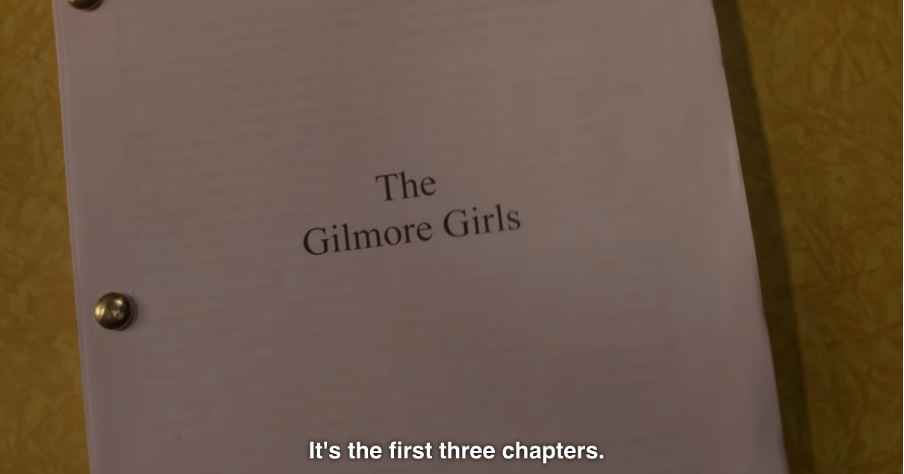

Something else left the audience of the revival perplexed: uncharacteristically for the Rory we came to know in Gilmore Girls, in A Year in the Life we never see her reading.17 There is just one scene where we see her with (but not reading) a book, Anna Karenina.18 Tolstoy's novel first appeared in Gilmore Girls's first season, where Rory describes it as one of her favorite books.19 That Rory returns to Anna Karenina in A Year in the Life underscores the main theme of the revival's third episode, "Summer": despite her many protestations that she's "not back" and that she's "just here temporarily," Rory is indeed back where we first encountered her all those years ago, home, in Stars Hollow. And this move back home, with no job or plans for the future, stinks of failure. In "Summer," and A Year in the Life more broadly, Rory is struggling to fulfill her aspirations and is adrift, which the revival symbolizes through the dissolution of that fundamental relationship that has fueled her ambition and drive to achieve throughout: her relationship with the world of books. That Rory then manages to find purpose and direction again by writing a book — a meta-memoir about herself and her mother titled Gilmore Girls — therefore rekindling this relationship, is telling. Dean even reappears in the revival just to sanction Rory's memoir plan by bringing us back to that iconic image of Rory reading with gusto: "You've read 'em [books] all, so what else are you gonna do?"20 A less charitable interpretation of Dean's sentence, and of Rory's voracious reading, is of course also possible, namely, that neoliberal logics of competition and consumption have become part of the way reading itself is now understood — think, for instance, of the "Rory Gilmore Reading Challenge" itself.

But before we get to the meta-memoir resolution, A Year in the Life shows us a struggling Rory. In the revival's first episode, "Winter," Rory is desperately trying to keep up the pretense of being a successful achievement-subject. When her grandmother Emily (Carole "Kelly" Bishop) questions the idea of, as Lorelai puts it, "On The Road-ing it" — having no fixed address and traveling "wherever there's a story to write," crashing with family and friends — Rory responds defensively: "I know exactly what I'm doing. I'm busier than I've ever been. I'm traveling and pursuing a goal." Yet she's clearly anxious about the turn her life is taking, a feeling that she tries to keep at bay by tap-dancing in the middle of the night to YouTube videos as a stress-release exercise and by repeating as a mantra "I have a lot of irons in the fire."21

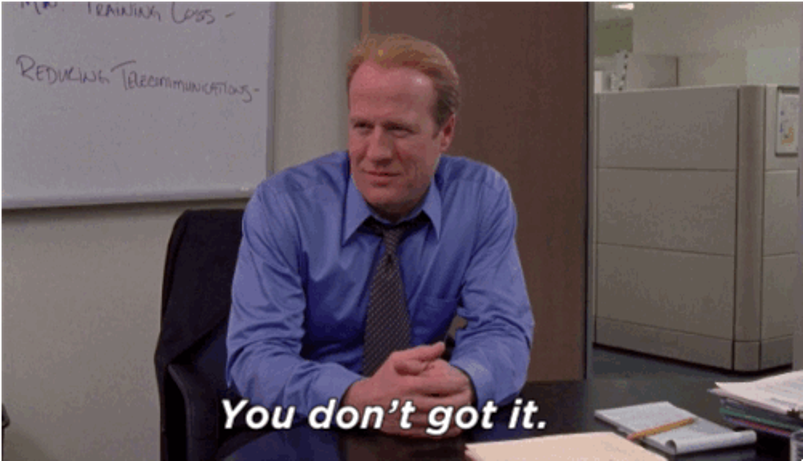

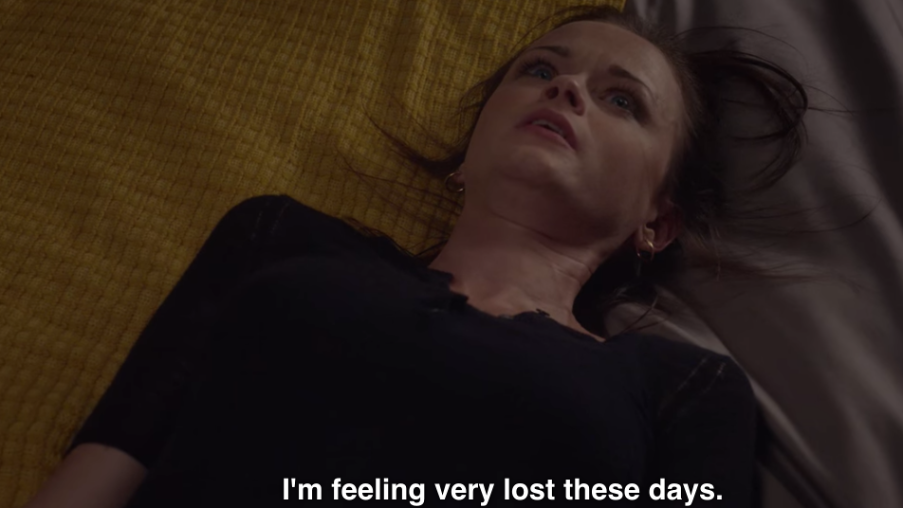

A Year in the Life's second episode, "Spring," sees Rory completely unravel. Writing projects fall through and Rory finally admits to Lorelai that she's feeling lost: "I'm blowing everything. My life, my career . . . I'm flailing, and I don't have a plan, or a list, or a clue."22 Several commentators are of the Mitchum Huntzberger's school of thought — Mitchum (Gregg Henry) was Rory's boss during an internship at a newspaper in Gilmore Girls's season 5 — and put this failure down to the simple fact that Rory is a terrible journalist.23 Their bulleted lists of reasons why Rory just "doesn't got it," to use Mitchum's brutal words,24 are admittedly compelling. The fact that Rory hasn't managed to have much of a successful career despite the enormous privilege and connections she has access to as a member of the Gilmore dynasty is, potentially, even more damning of Rory's abilities.

And yet, when I look at Rory in A Year in the Life, I also see somebody illustrating what achievement subjectivity feels like. Han's core argument in The Burnout Society is that the imperative of the "Unlimited Can" produces burnout and depression. Han writes that "the exhausted, depressive achievement-subject grinds itself down, so to speak. It is tired, exhausted by itself, and at war with itself. [ . . . ] It wears out in a rat race it runs against itself".25 Rory is exhausted by a life spent being an entrepreneur of herself, endlessly laboring on project after project, chasing achievement after achievement.26 She can't sleep because she finds it impossible to switch her mind off work — hence her late-night tap-dancing sessions. Ultimately, Rory reaches a point when the imperative of the "Unlimited Can" is impossible to sustain any longer and she simply can't anymore; even reading has become too much. The escape into the world of books, a reminder of her ambitions and missed achievements, is foreclosed.

And it's not just Rory who is shown collapsing under the weight of achievement subjectivity in A Year in the Life. Paris (Liza Weil), Rory's frenemy since the Chilton school days, is seemingly the successful achievement-subject par excellence: she owns the "largest full-service fertility and surrogacy clinic in the Western hemisphere" and has completed an impressive list of qualifications — she's an "MD, a lawyer, an expert in neoclassical architecture and a certified dental technician to boot" — which signify in their disparate assortment an almost compulsive drive to achieve. Yet Paris also feels "untethered," like a "mylar balloon floating into an infinite void".27 Similarly, Luke's daughter, April (Vanessa Marano), a successful grad student at MIT, has an anxiety attack when she sees Rory back in her childhood room, fearing that Rory's fate might be her own in the near future.28 Even the "thirty-something gang" who, like Rory, are back in Stars Hollow after college with no prospects, despite being relentlessly mocked by the show for their traumatized ineptitude, seem to hint at the fact that something isn't quite right with the model of education and work our society is predicated upon.29 Where Gilmore Girls celebrated the promises of endless entrepreneurial drive, therefore, A Year in the Life shows its cracks, in particular the unbearable pressures this drive exercises on us. A Year in the Life, however,also gestures at how hard it is to let this drive go, even when it fails us.

Thus, Rory frames her Gilmore Girls book as her last desperate stab at achieving her fantasy of the dream writing job: "Without this [memoir]," she tells Lorelai, "it's groveling for jobs that I don't want".30 To know whether this wager has been successful we might need a second reboot.

Dr Diletta De Cristofaro (@tedilta) is a Research Fellow based between Northumbria University in the UK and Politecnico di Milano in Italy. She writes about contemporary culture, crises, and the politics of time. She is the author of The Contemporary Post-Apocalyptic Novel: Critical Temporalities and the End Times (Bloomsbury, 2020). She is currently working on a new book project about representations of sleep and the sleep crisis — the idea that contemporary society is profoundly sleep-deprived — across contemporary fiction, non-fiction, and digital culture.

References

- Gilmore Girls, season 1, episode 1, "Pilot," directed by Lesli Linka Glatter, aired October 5, 2000, on The WB.[⤒]

- Cf. Anna Viola Sborgi, "'The Thing That Reads a Lot': Bibliophilia, College Life, and Literary Culture in Gilmore Girls," in Screwball Television: Critical Perspectives on Gilmore Girls, edited by David Scott Diffrient and David Lavery (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010), 186-201; see specifically 187: "Rory's bibliophilia — her love of reading and writing printed words — is not likely to be found in other contemporary television series depicting teenage life." Numerous Internet pieces also praise, and indeed thank, Rory for her unabashed love of literature. See, for instance, Selina Falcon, "Thank You, Rory Gilmore," Bookriot, December 31, 2018.[⤒]

- Cassie Gutman, "The Rory Gilmore Reading List: How Novel," Bookriot, January 8, 2021. [⤒]

- "Although marketed toward a gender and age demographic substantially different from the audiences of other programs deemed to be exceptional [such as The Sopranos or The Wire . . . ] Gilmore Girls nonetheless explicitly and repeatedly invites similar viewing strategies by relying upon what French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has termed 'cultural capital.'" Justin Owen Rawlins, "Your Guide to the Girls: Gilmore-isms, Cultural Capital and a Different Kind of Quality TV," in Screwball Television, 36-56, 37. Rawlins also remarks, however, that "while other quality shows solicit and most often appeal to those viewers possessing cultural capital, those programs' intertextuality and prerequisite cultural knowledge often go unacknowledged within the diegesis and lead to a rigid divide between those 'in the know' and those not. Gilmore Girls, on the other hand, openly discusses and questions the nature of cultural capital by repeatedly examining its relation to education and socioeconomic status" through Gilmore-isms that "are often commented upon and frequently become the focus of conversation." See Gutman, "Reading List," 37. [⤒]

- Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 9. On Gilmore Girls's neoliberal politics see also Molly Geidel, "On the Entrepreneurial Feminism of Stars Hollow," Avidly, December 6, 2016, and Daniela Mastrocola, "Performing Class: Gilmore Girls and a Classless Neoliberal 'Middle Class,'" Studies in Popular Culture 39, no. 2 (Spring 2017): 1-22.[⤒]

- Gilmore Girls, season 3, episode 22, "Those Are Strings, Pinocchio," directed by Jamie Babbit, aired May 20, 2003, on The WB.[⤒]

- Han, The Burnout Society, 8. The way literature works here as the fuel of the neoliberal "Unlimited Can" is in direct opposition to how literary culture is conceived in another TV show examined in this cluster, Lodge 49. See Arin Keeble's essay "The Ordinary Literary World of Lodge 49," Post45 Contemporaries, November 2021.[⤒]

- Molly Geidel, "On the Entrepreneurial Feminism of Stars Hollow."[⤒]

- Gilmore Girls, season 1, episode 22, "The Lorelais' First Day at Chilton," directed by Arlene Sanford, aired October 12, 2000, on The WB.[⤒]

- Matthew C. Nelson, "Stars Hollow, Chilton, and the Politics of Education in Gilmore Girls," in Screwball Television (Syracuse University Press: 2010),202-213, 213.[⤒]

- Sborgi, "'The Thing That Reads a Lot,'" 197, 199.[⤒]

- Gilmore Girls, season 7, episode 22, "Bon Voyage," directed by Lee Shallat-Chemel, aired May 15, 2007, on The CW.[⤒]

- Han, The Burnout Society, 9.[⤒]

- Gilmore Girls (@GilmoreGirls), "Just a couple of girls talking about books...," Twitter, June 25, 2016. [⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 1, "Winter," directed by Amy Sherman-Palladino, aired November 25, 2016, on Netflix.[⤒]

- Cf. viewers' reactions to the revival collated in Jonathan Gray, Dislike-Minded: Media, Audiences, the Dynamics of Taste (New York: New York University Press, 2021), 118-122. Gray notes that "Rory was overwhelmingly discussed as someone a lot of viewers saw like themselves. When her AYITL iteration seemed stalled in terms of maturity, made bad decisions, and seemed significantly less confident in her abilities than before, this created a notable rupture that felt to some respondents like an attack on their generation, as if the writers were now casting aspersion on the notion that someone like themselves could (continue to) succeed." See Gray, Dislike-Minded, 121.[⤒]

- Lili Loofbourow, "The Decline and Fall of the Gilmore Girls," The Week, December 1, 2016.[⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 3, "Summer," directed by Daniel Palladino, aired November 25, 2016, on Netflix.[⤒]

- Gilmore Girls, season 1, episode 16, "Star-Crossed Lovers and Other Strangers," directed by Lesli Linka Glatter, aired March 8, 2001, on Netflix.[⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 4, "Fall," directed by Amy Sherman-Palladino, aired November 25, 2016, on Netflix.[⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 1, "Winter."[⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 2, "Spring," directed by Daniel Palladino, aired November 25, 2016, on Netflix.[⤒]

- See, for instance, Megan Garber, "Turns Out, Rory Gilmore Is Not a Good Journalist," The Atlantic, November 28, 2016; Saba Hamedi, "Rory Gilmore Is Not a Good Journalist," Mashable, November 21, 2016; Jen Chaney, "Rory Gilmore and Why We Need Better Fictional Journalism," Vulture, November 29, 2016. [⤒]

- Gilmore Girls, season 5, episode 21, "Blame Booze and Melville," directed by Jamie Babbit, aired May 10, 2005, on The WB.[⤒]

- Han, The Burnout Society, 42. [⤒]

- On the endless nature of this entrepreneurial drive cf. Han, who argues that "a definitive work, as the result of completed labor, is no longer possible today," and that "the feeling of having achieved a goal never occurs"; Han, Burnout, 38, 39-40, emphasis in original. [⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 2, "Spring."[⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 3, "Summer." [⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 3, "Summer."[⤒]

- A Year in the Life, episode 3, "Summer."[⤒]