New Literary Television

Why should we pay attention to the "literary" or "cinematic" dimension of a TV series? For some critics, approaches that focus on media and artistic convergence are likely to distinguish some specific works which would thus be "liberated" from their low-brow televisual context, to be "elevated" among other more established forms such as literature or cinema.1 In an epoch in which the "complex" or "prestige" TV series is increasingly considered as an art form, and as some series are likely to be canonized next to the "great works of the past," isn't it nefarious to reinstate cultural and artistic hierarchies in a field — TV studies — which had pointedly been set up to resist them?2

This essay will argue that, even if the use of the terms "cinematic" and "literary" can be criticized when applied to prestige TV, it is hard to simply dismiss this usage when it is so widely used by viewers, critics, and scholars alike to refer to shows from the past two decades.3 Pragmatically, as this recurrent usage testifies, these terms do apply in the emotional, intellectual, and imaginative phenomenon of reception, and analyzing what these qualifiers mean when they are applied to TV allows us to understand how they reveal the constant dialog between stories, artworks, and cultural products in our hypermediatized world. Analyzing processes of circulation between scripted series and other art forms does not necessarily imply hierarchy; it can also acknowledge the rich intertextual nature of the fundamentally "impure"4 form of the TV series. As critic Matt Zoller Seitz puts it, we need to pay close attention to "scripted television's raiding of literature for devices that it places in service of its own storytelling, then transforms into something that's part literature, part cinema, but ultimately and distinctively television."5 Studying literary features, devices, or references in TV thus reveals, to quote Ronan Ludot-Vlasak, "signifying practices that shouldn't be limited to sociological issues,"6 since they fundamentally contribute to the processes of audience participation and engagement that lie at the heart of the pleasure provided by the serial form.7

The choice of Fargo (FX, 2014-2020) as a case study for "literary TV" may seem paradoxical, since the show places itself directly in the line of cinema rather than literature. It is an adaptation (in the broad sense of the term), not of a literary work, but of the 1996 Coen brothers film with which it shares a title. All four seasons take place in the rural Midwest, and propose variations on similar aesthetics and themes, depicting ordinary people exposed to extreme violence who end up confronting organized crime. But the series never fits into any clear category associated with adaptation. It is neither spin-off nor remake, neither reboot nor sequel. It defies our taxonomies.

The anthology — especially in its first three seasons, which this article will mainly focus on — also resorts to what we could consider literary devices, effects and references, which is not suprising considering the fact that its creator, Noah Hawley, is also a novelist.8 Fargo the series is thus, in essence, dialogic, in the sense that it positions itself in a deliberate conversation with many other works of all kinds, ranging from all of the Coens' films to Alice in Wonderland (1865), from the Bible to Peter and the Wolf (1936). It is this diversity of intertexts which makes it a particularly interesting example to reflect on what it means to call a series "literary" today, and why that matters. Indeed, because of this multiplicity of intertexts, the series manages to explore the frontiers of what we mean by "literary," "cinematic," and ultimately "televisual." To quote Thomas Elsaesser, what is most interesting to study here is "the erosion of established boundaries."9 The series investigates these boundaries by exploring the interplay between text and image, and by evoking and mixing different modes of storytelling and representation, in order to reflect on fundamental questions of truth, meaning, logic, human values, or more generally, how to make sense of the world when it veers into chaos and absurdity. In doing so, it also reflects on the nature of its own representation as a TV show, by acknowledging the nature of the form as, fundamentally, an amalgam.

1. Words and images: deconstructing the "true story"

If we start with a broad definition of "literary" — that is to say anything that is connected with the written word — we notice that Fargo explores the use of written text onscreen, and reflects on the connection between word and image both in its storyline and in its aesthetic treatment of writing on screen. After illustrated literature, advertising, and cinema, TV series in their turn have been exploring the complex association between text and image, proposing many forms of hybridation, and contributing to the building of "new textual frontiers."10 The long duration and the episodic nature of TV series particularly allows the aesthetic and narrative exploitation of paratexts such as titles, epigraphs, or diverse forms of writings on the screen. The serial format notably allows variations and modulations around the semiotic and expressive instability of texts, by modifying the context or modes of apparition of a similar text from one episode to the next.

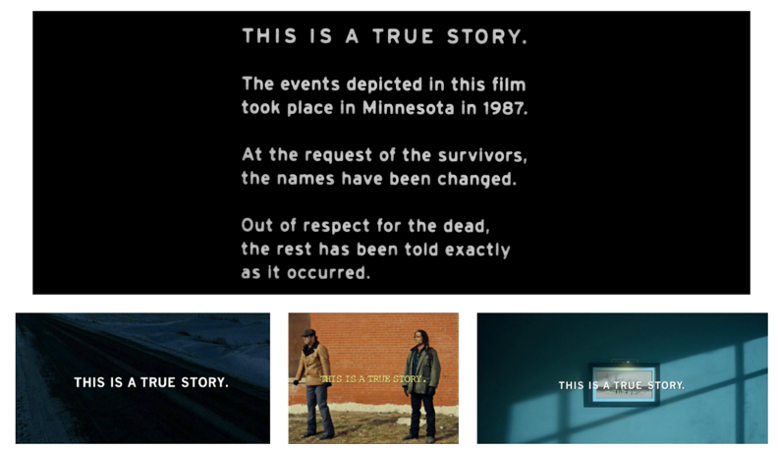

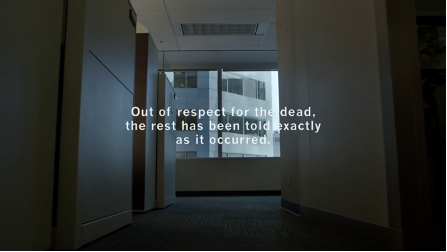

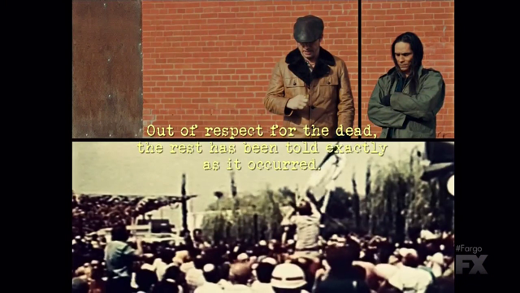

Fargo thus uses the written text as symbol both of its adaptive nature and of its playful relationship with fiction and truth. The connection with the 1996 film is indeed established by what we could see as a literary matrix — the words inscribed on the screen at the opening of each episode precisely echoing those that opened Fargo, the film.

Whereas this disclaimer might have been taken at face value by the original viewers of the film, it was eventually revealed as a "paradoxical paratext" when it was denounced by another disclaimer in the end credits.11 This reads: "The story is fictitious. No identification with actual persons (living or deceased), places, buildings, and products is intended or should be inferred."12 The initial text therefore appears as a narrative and aesthetic principle of parody, "in the root sense of the term: it parrots the commonly made truth claims of fact-based narrative, only to be comically contradicted by an opposing statement at the other end of the movie."13

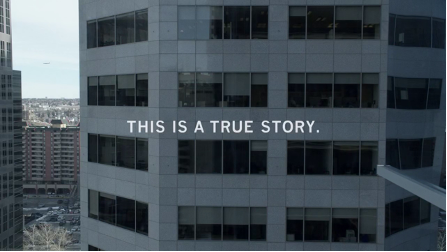

By having these sentences recur at the beginning of every single episode, the series turns them into an idiosyncratic title sequence, expanding their literary and paradoxical value. Indeed, not only is this initial text contradicted by a similar final claim, in each episode, that everything is indeed fictitious, but because of its recurrence, it also tends to lose its quality as a contractual message to become more of a refrain whose obviously deceitful claim is gradually eclipsed by its aesthetic and symbolic nature. The playful engagement with these sentences is manifest, not just in their repetition, but also in the way the words themselves are incorporated into the audiovisual texture and submitted to different variations, becoming graphic elements and not only transparent signifiers. Whereas the text appeared as one block in the 1996 film, it is now most often distributed as four separate blocks, each associated to a different shot, which endows every sentence with a new context. For instance, in season 3, episode 8, "Who Rules the Land of Denial," every word of "this is a true story" appears separately, on different shots, while in season 1, episode 3, "A Muddy Road," each sentence is associated with a new step in the establishing sequence and the classical progression from the exterior to the interior of a building where the action is about to take place.

Fig. 2: Opening disclaimer on the establishing sequence of Fargo, season 1, episode 3, "A Muddy Road."

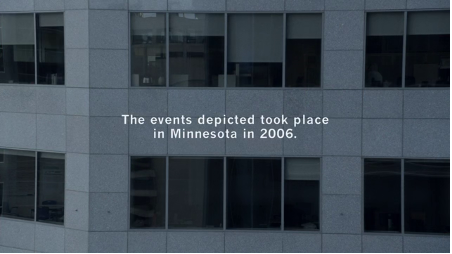

The kinetic treatment of the text, the way the words fade in or fade out, and the manner in which they combine with the image to create graphic or rhythmic effects, are also used to enhance their paradoxical nature. For instance, in most of seasons 1 and 2, the word "true" remains on screen longer than the rest of the sentence, so that it appears on its own for a few moments. In season 2, episode 1, "Waiting for Dutch," the word "true" remains alone over archive footage of Jimmy Carter's famous "crisis of confidence" speech, which sets up the historical context of the season. In this first episode taking place in 1979, these are indeed "true" images of a "real" historical period, but the use of archive footage remains limited to the introductory montage sequence14 and the rest of the historical background is pure fictional reconstitution and elaborate mise en scène.

Fig. 3: Mixing "true" and "fictional" images in Fargo, season 2, episode 1, "Waiting for Dutch."

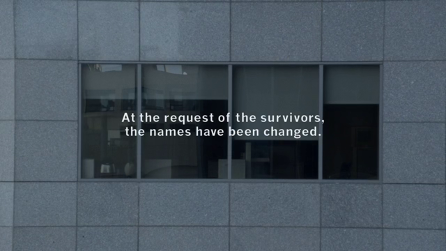

In season 3, on the contrary, the word "true" fades out first, leaving an empty space between article and noun: "this is a [ . . . ] story." Our imagination can fill the gap left by this symbolical disappearance of the "true," and we project our own interpretation of this absent truth onto the empty space. The word "story" then remains longer on screen, in a clear assertion of the primacy of story over truth.

Fig. 4: The animation of text materializes the primacy of the story in Fargo, season 3, episode 3, "The Law of Non-Contradiction."

Since season 3 deals primarily with the dissolution of truth in a corporate, disembodied environment, with extensive manipulations of appearances, this initial vanishing of the word "true," and the gap that remains instead, can be seen as a both linguistic and graphic representation of the "post-truth" moment on which the season reflects.

2. The History of True Crime in the Midwest

Intersections between the real and the fictional lie at the heart of the pleasure provided by contemporary television. They are part of what Jason Mittell calls our "modes of engagement," our desire to "drill" into the details of an episode to see connections between the fictional elements and potential real-world antecedents.15 In the case of Fargo, since the assertion that "this is a true story" is quickly deconstructed from the start, what remains is the pleasure of drilling into the series in order to lose ourselves in the complex intertextual web it weaves with a variety of narratives, films, texts, myths, and other artworks. Series like Fargo position themselves as literary "in the second degree" — palimpsestic works conjuring many other literary texts (among other references) that came before them. If this referential dimension could already be found in series like Moonlighting, for instance, then a high degree of referentiality and intertextuality has become more particularly characteristic of the serial format in the past thirty years.

It would be endless (and somewhat pointless) to make a list of all intertextual references, quotations, allusions or pastiches in Fargo, which is very much about how stories, through successive retellings and appropriations, are led to change and mutate, are reinterpreted to convey different meanings, are used and misunderstood. By questioning the making of meaning through diverse narratives from the past and fictional imaginary intertexts alike, the series situates itself within the larger framework of many other pre-existing narratives, and thus constructs its own complexity and ambiguity as fictional work, while at the same time "questioning the possibility of an immutable, immovable text."16

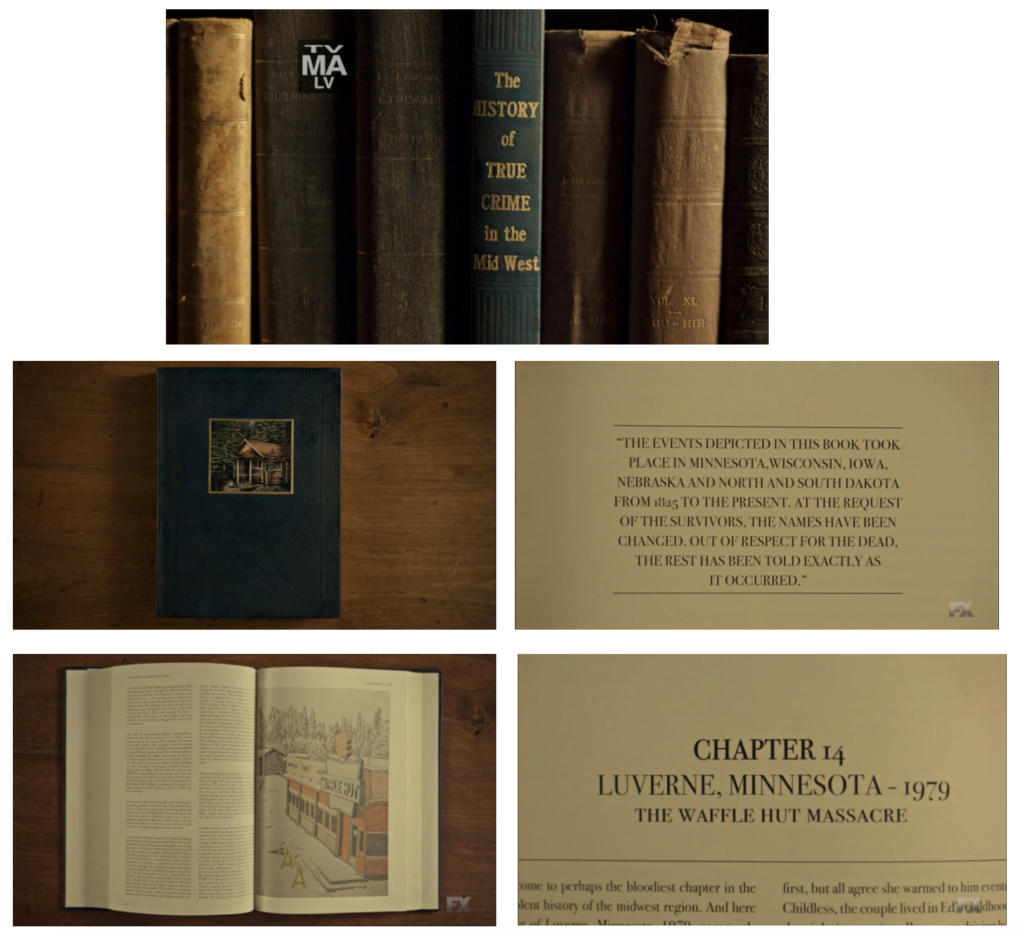

This inscription of the series within a long literary and cultural tradition particularly stands out in season 2, episode 9, "The Castle," where the initial sequence imagines that our story, like the others preceding it, actually belongs to a book called The History of True Crime in the Mid West, written by fictional historian, "Barton Brixby." This fictional historical book is presented by the sequence as an urtext of sorts. A focus on its old, elegant binding, then on its cover, followed by flipping of the pages, brings us back to an old cinematic device associated with fairy tales and classical adaptations, and is accompanied by another such device — the use of the literary voiceover narration.17

These devices participate in the creation of a wider storyworld, or what Allan H. Redmon calls a metanarrative that manages, at this specific moment, to bring together the 1996 film and the different seasons into a coherent whole, to convey "the idea that these stories have some kind of connection, that there is some book that they're all part of."18

However, Hawley and the creative team do not attempt to close this storyworld thanks to this inclusion of a metanarrative, but on the contrary they acknowledge it as open, fluid and fictitious. For Redmon, this is

an invitation to participate in the process of adaptation that Hawley's first season initiates rather than completes. [ . . . ] The references become a means to keep that process alive and active. [ . . . ] They favor the individual text that each viewer will construct between the text they are given and the text they know is being referenced. If any master text is to emerge, it is the one the viewer constructs.19

What the series reflects on, more generally, is thus the constant process of retelling, recycling and reinterpreting that our culture is made of. The use of literary references in this sense is also a way to inscribe this intertextual play in a longer history, to consider the series as a recent participant in the long-standing game of sharing and appropriating of stories.

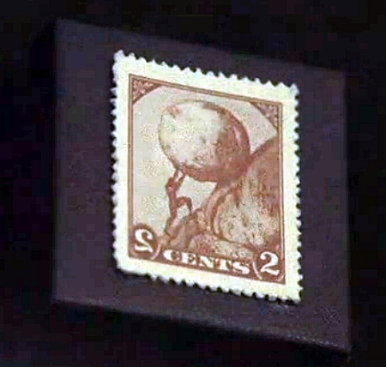

No wonder, then, that figure of Sisyphus should punctuate the series — by providing the title for season 2, episode 3, "The Myth of Sisyphus," and then through Albert Camus's book, Myth of Sisyphus (1942) which can be seen in the hands of Noreen, the young sales assistant in the butcher shop where Ed Blumqvist works. She is presented as a teenager in her nihilistic phase, questioning the meaning of life through her somewhat distorted understanding of Camus's prose.

Her own brush with death, and later on her conversations with Betsy, Lou's wife who is dying of cancer, will help her overcome this nihilism and embrace human interaction in a way that is much closer to Camus's conclusions. In season 3, the myth of Sisyphus reappears, not in the form of a text, but in the form of an image, since it is the drawing of the tragic figure pushing his rock uphill that ornaments the stamp which Ray Stussy desperately wants to retrieve, and that has become, with time, synonymous with his personal failure.

The figure of Sisyphus metaphorically encompasses the mutability of references and common stories, since in the series it appears as a Greek myth, a philosophical text, and an image on a stamp. It is used as an analogous reference tool to reflect on the torments of the characters and their struggles — which is not particularly original since, as myths are bound to do, it can universally and eternally apply to motifs of doomed human struggle. But in Fargo it also works as a theoretical paradigm to reflect on the show's own medium, on this serial format which pushes its narrative rock to the top of each episode, or each season, knowing full well that it will go down again and lead to constantly renewed dramatic ascensions. Whereas in a post-modern moment Sisyphus could have been seen as embodying the ontological absurdity of fiction-making, especially in terms of literary representation at the age of suspicion as Nathalie Sarraute conceptualized, in our post-postmodern era, we may have become Camusian about the impossibility of closure, and adopted the idea that "the struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man [or a woman]'s heart."20

If this metaphor, redolent of a multiplicity of stories related with existential angst and absurdity in Fargo, seems to point to the absurdity of telling stories, indeed of any attempt to capture truth, it also acknowledges the ineluctable need to do so, as a redeeming power. The example of Sisyphus is thus just one example of the way the series asserts itself, not just as a writers' medium, but as a "writerly medium" in the sense of Roland Barthes, that is to say a form that does not merely satisfy the audience's expectations but demands that those expectations be questioned, and that the viewers adopt an active role in the construction of meaning.

Ariane Hudelet is Professor of visual culture at Université de Paris (LARCA research unit/CNRS) where she teaches in the English department. She recently edited Exploring Seriality on Screen with Anne Crémieux (Routledge 2021); she is the author of The Wire, les règles du jeu (Presses Universitaires de France, 2016) and the co-editor of the TV/Series journal.

References

- Elana Levine and Michael Z. Newman, editors, Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status (New York: Routledge, 2011); Deborah Jaramillo, "Rescuing Television from 'The Cinematic': The Perils of Dismissing Television Style," in Television Aesthetics and Style, edited by Jason Jacobs and Steven Peacock (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 67-77; Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (New York: NYU Press, 2015). [⤒]

- "Television studies would be born in and from this moment in which it became vital to inquire into a text's ideological role. Formal analysis would still prove important, but television studies tended to engage in formal anlaysis primarily as a means to the end of determining any give show's place within a network of power." Jonathan Gray and Amanda Lotz, Television Studies (Cambridge: Polity, 2012), 39.[⤒]

- TV series have notably acquired a privileged position in literary conversations, as noted by Dan Hassler-Forest, who writes that "when the most frequently discussed question within a university's English literature department is no longer 'what book do you recommend?' but 'which series should I be watching?' [ . . . ] something has certainly changed." Dan Hassler-Forest, "Game of Thrones: Quality Television and the Cultural Logic of Gentrification," TV/Series 6 (2014). [⤒]

- I am here using the term in the sense developed by André Bazin and Alain Badiou, meaning notably that cinema borrows elements from other arts, and constitutes an indistinguishable zone between art and non-art. André Bazin, Qu'est-ce que le cinéma? (Paris: Cerf, 1976); Alain Badiou, Petit manuel d'inesthétique (Paris: Seuil, 1998). [⤒]

- Matt Zoller Seitz, "Television's Best Shows Are Taking Their Cues From Literature," Vulture, May 17, 2017. [⤒]

- Ronan Ludot-Vlasak, "Les Séries télévisées au prisme de l'intertextualité: quelques perspectives sur les frontières du littéraire," TV/Series 12 (2017).[⤒]

- Jennifer Hayward, Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009); Frank Kelleter, editor, Media of Serial Narrative (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2017).[⤒]

- Hawley has published five novels: A Conspiracy of Tall Men (1998), Other People's Weddings (2004), The Punch (2008), The Good Father (2012), and Before the Fall (2016). Many other showrunners are also novelists or short story authors, such as Nick Pizzolatto (True Detective), David Benioff and D.B. Weiss (Game of Thrones), Joe Weisberg (The Americans), and Jim Gavin (Lodge 49).[⤒]

- Thomas Elsaesser, "Literature after Television: Author, Authority, Authenticity," in Writing for the Medium. TV in Transition, edited by Thomas Elsaesser, Jan Simons and Lucette Bronk (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1994), 137-148, 138.[⤒]

- Jeffrey Sconce, "What If? Charting Television's New Textual Boundaries," in Television After TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, edited by Lynn Spigel and Jan Olsson(Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 93-112.[⤒]

- Davis Sterritt, "Fargo in Context", in The Coen Brothers' Fargo, edited by William Luhr (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 10-32, 17.[⤒]

- Fargo, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen (Universal City: Gramercy Pictures, 1996).[⤒]

- Sterritt, 19.[⤒]

- And even here, it is associated with fictional scenes since the split screen associates archive footage and shots of the fictional characters.[⤒]

- Jason Mittell, "Forensic Fandom and the Drillable Text," Spreadable Media,December 17, 2012; Mittell, Complex TV.[⤒]

- Shannon Wells-Lassagne, "Literature and TV/Series", TV/Series 12 (2017).[⤒]

- A literary technique that has become more and more widespread and diverse in recent series, from House of Cards (Netflix, 2013-2018) to The Handmaid's Tale (Hulu, 2017-), from Mr. Robot (USANetwork, 2015-2019)to Jane the Virgin (The CW, 2014-2020).[⤒]

- "Audio Commentary," season 2, episode 9, "The Castle," Fargo, directed by Adam Arkin (2015; 20th Century Fox, 2016), DVD.[⤒]

- Allen H. Redmon, "'This is a [ . . . ] Story;' The Refusal of a Master Text in Noah Hawley's Fargo," Linguaculture 7, no. 1 (2016): 16-26.[⤒]

- Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus (New York: Vintage, 1991), 123.[⤒]