New Literary Television

1.

Lovecraft Country's first season (2020) exemplifies recent prestige television's changed relationship to "the literary" in that it rejects the authority of "the novel," as a form entangled within centrist liberalism's epistemic and embodied violence. Along with contemporary graphic narrative, the new prestige television abandons the ideals of liberal pluralist consensus and national imaginaries, caught in slogans like "the Great American Novel" or "water-cooler TV," in order to enable an intersectional left culture. Deploying what I have elsewhere called speculative nostalgia, Lovecraft Country stages the confrontation between "equality" (white) feminism and a BIPOC alternative lifeworld to reject the former's insistence on a social history of sequential uplift (a history marked by inaugural "firsts" for the formerly excluded) in favor of a vision of collective self-care.1

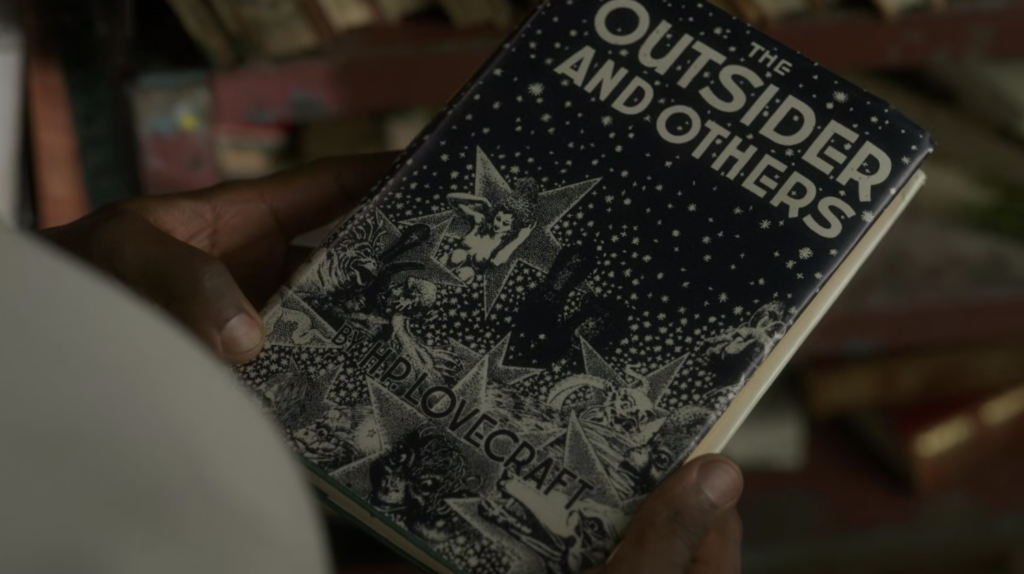

Lovecraft Country carries this project through a persistent engagement with alternative print culture. The entire season spends an inordinate amount of screen time showing viewers images of book covers. But the texts offered for our recognition are rarely ones of consecrated novels found in elite syllabi. Instead, these titles come from the realm of so-called pulp fiction or self-publication. The motive for this replacement of more canonical texts is staged as the conflict between Black and white families over who gets control over The Book of Names, a constitutional grimoire dating back to the American colonial period. This search exemplifies Lovecraft Country's own declaration of literary independence as it liberates itself from a founding fathers' textual legacy twice over. Shortly after the first episode the show discards any serious links to its eponymous author, H.P. Lovecraft. Even figures from Lovecraft's cosmology, such as the shoggoths, are not closely observed, since the show's depicted shoggoths have no similarity to Lovecraft's toothless, protoplasmic blobs. By mid-season the show's original source novel, Matt Ruff's Lovecraft Country (2016) has its plot arc abandoned. Pursuing Afrofuturist storylines instead, Lovecraft Country self-authorizes through a time travel sequence in which Atticus Freeman returns from the future, holding a copy of a paperback entitled Lovecraft Country, a lightly fictionalized account of Freeman's life that will be written by his as-yet unborn son.

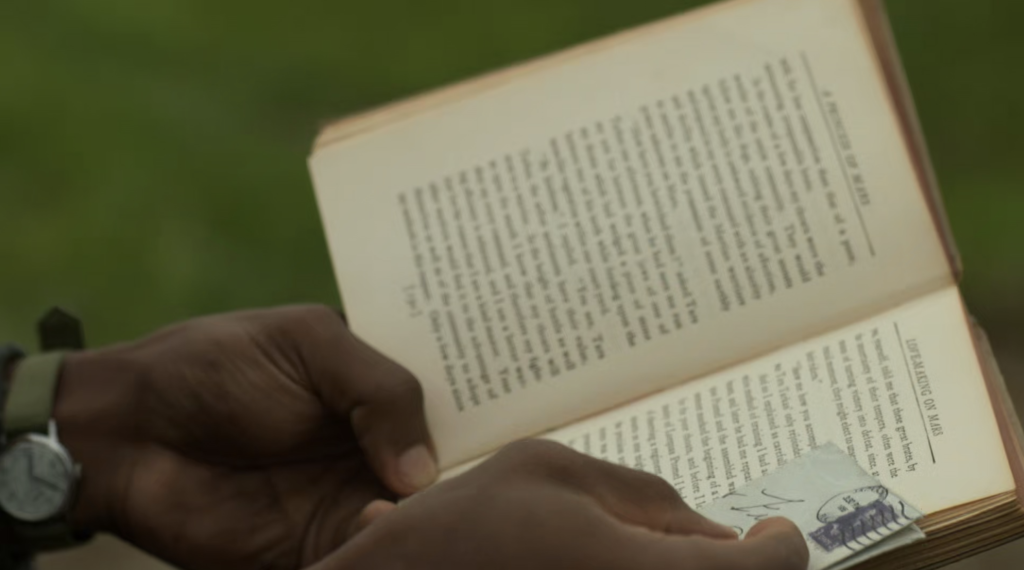

Lovecraft Country registers its own starting point of departure from liberal fantasies of national inclusion as its assumed protagonist is shown wearing Jackie Robinson's baseball uniform after an opening voiceover: "This is a story of a boy and his dream, but more than that it is the story of an American boy in a dream that is truly American."2 But as Langston Hughes suggests, this dream will "stink like rotten meat."3 Furthermore, Lovecraft Country will not even be entirely a boy's story, but one finally about non-white mothers and daughters. For if the series has any direct textual lineage, it is less to Lovecraft's fiction than to Edgar Rice Burroughs's A Princess from Mars (1912). The first episode begins with Atticus awakening from a dream about World War I with a copy of the 1917 Grosset and Dunlap edition of Burroughs's novel in his lap. Later in that episode, the camera shows Atticus reading the pages where the book's protagonist, ex-Confederate soldier John Carter, explains how he tames Mars's horse-like creatures, the thoats, by patting them on the head. Atticus will then repeat the gesture with the show's shoggoths, who look like thoats. But just as Carter gets eviscerated in a later episode, where he seems to be killed while leading Confederate soldiers against a phalanx of quasi-African, extra-planetary female warriors, Atticus himself is replaced as he likewise dies. Instead the first season's final shot is of Diana Freeman, Atticus' niece, with her own shoggoth baying at the moon in a way that visually recalls Frank Frazetta's 1970 Doubleday paperback cover illustration for A Princess of Mars. The series ends, then, not with Lovecraft's male-centric tales, but with a surrogate for the non-white female of Burroughs's title.

Similarly, in rejecting the consecrated novel-form as the source of its own alternative textual lineages (preferring the spoken word music of post-war Black arts, usually by women), Lovecraft Country disavows status desires carried within the prior "Golden Age" of 1990s-2010s prestige television about angry white men feeling aggrieved at the erosion of their entitlement. When American journalists first sought to come to terms with the shift from episodic television (which introduces and resolves a relatively stand-alone plot within a single episode) to serial or long-form television (which uses an entire season, or predetermined, limited set of seasons), they quickly turned to the novel-form as the most intelligible illustration of what this emerging kind of television was doing. David Lavery in the New York Times presented The Sopranos as having "the feel of an as yet unfinished nineteenth-century novel [with] plot twists reminiscent of Dickens [... and with] underlying themes [that] evoke George Eliot: the world of Tony Soprano is a kind of postmodern Middlemarch."4 Soon thereafter even showrunners took up the novel's mantle as a way of gaining status for an otherwise uncelebrated medium. David Simon self-reflexively named an episode in The Wire's season 5, "The Dickensian Aspect," to indicate how viewers should also consider the show.5 Yet despite literary critics' relief that prestige television might come to revalue fiction, to gain a full sense of Lovecraft Country's project, we first need to locate it within a longer historical context to learn why it rejects the novel as its literary foundation.

2.

The literary relations of contemporary prestige television register structural transformations within the capitalist world-system resulting from the dual temporalities synchronizing at the current moment: the end of a long secular trend of 200-ish years, beginning in the late eighteenth century, and the rise of neoliberalism's third rhythmic cycle, presumably once more of 40-60 years, that emerged in the wake of the 2008/11 crash.6 This periodicity energizes the more interesting work happening today in television and graphic narrative.

Following Marx's comments that historical capitalism concluded its "infancy" in the last third of the eighteenth century, Immanuel Wallerstein argues that this social minority was eclipsed as a result of the first major antisystemic challenge involving the inter-connected American, French, and Haitian Revolutions and the rebellions in Ireland, Egypt, and among the indigenous peoples of South America (in conflicts associated with Túpac Amaru II).7 While these disturbances had varying degrees of success, their combined effect produced two new social truths: continual social transformation ("modernization") would be a normal constant and rule by sovereign forces of lineage elites would be replaced by forms of popular and democratic government.

For Wallerstein, three overall political tactics (what he called "ideologies") arose in response: first, conservativism and (centrist) liberalism, and then slightly later, radicalism (Marxism). Conservatism sought to deny the onset of these post-revolutionary realities by resorting to backwards-looking social forms through the defence of tradition, deference to lineage and landed elites, subservience to ministered religion, and dogged insistence on trans-historical notions of "custom," the patriarchal family, "tradition," and "common sense." Radicalism, on the other hand, sought not only to embrace these new truths, but also to accelerate their onset through disruptive breaks, i.e. revolution.8 Centrist liberalism accepted the inevitability of these changes (Tocqueville's introduction to Democracy in America is exemplary), but sought to diminish their explosive potential, moderating and regulating their metabolism. It did so by gradually expanding access to voting suffrage, as the political instrument of representation, and entry to institutions of higher education, the apparatus that credentialized the bureaucratic managers who would become society's administrators based on their certified merit rather than aristocratic aura or aesthetic connoisseurship.

Of the three, centrist liberalism would become so dominant that even many forms of conservatism and radicalism adopted several of its positions. Centrist liberalism became successful because its model best ensured the continuity of capitalism's accumulation for accumulation's sake, not least by proposing social science "laws" that would rationalize complexity into knowable and disciplinable categories. Liberalism managed (or muddled through) a series of capitalism's crises of profitability by facilitating the deployment of interlaced divisions, such as the separation of public and private spheres, capitalist profiteering and civil (bourgeois) society, and, above all, exclusion from active citizen subjectivity by the social death delivered to those considered to be exchangeable objects.

As Wallerstein explains:

The more equality was proclaimed as a moral principle, the more obstacles — juridical, political, economic, and cultural — were instituted to prevent its realization. The concept, citizen, forced the crystallization and rigidification — both intellectual and legal — of a long list of binary distinctions that then came to form the cultural underpinnings of the capitalist world-economy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: bourgeois and proletarian, man and woman, adult and minor, breadwinner and housewife, majority and minority, White and Black, European and non-European, educated and ignorant, skilled and unskilled, specialist and amateur, scientist and layman, high culture and low culture, heterosexual and homosexual, normal and abnormal, able-bodied and disabled, and of course the ur-category which all of these others imply — civilized and barbarian.9

Of all the cultural forms emerging throughout this long secular trend, it was the form of long-fiction categorized as the novel that best housed and managed these tensions for centrist liberalism, especially as it yoked together notions of individual genius and personal development with national imaginaries. As Benedict Anderson suggested, the novel sprang from print capitalism to create a fantasmic social identity through its reading and dissemination in state-backed institutions and educational curriculum, even while it also enacted a sense of unique private interiority, particularly as an object consumed in various states of intimate undress and positions of vulnerable isolation.10) This production of a liberal self flowered through disciplinary techniques of behavioral, emotional, and sexual normalization manifested through binary divisions. As Foucault offered, "there is probably an essential kinship between the novel and the problem of the norm."11 The novel-form became so dominant that it managed to effectively wipe out swathes of alternatives in what was a heterogeneous cultural ecology, allowing some to exist only on the margins as para-literature or experimental writing. Indeed, what we often call genre writing is best understood not through reference to a typology of figurations and plot devices, but as works that are devalued, while by far eclipsing the literary novel's commercial success, because they do not respect the structure provided by the novel for liberalism's governmentality. The novel's service to liberalism, on the other hand, can be seen in terms of its pulses of heightened production and commentary, tightly correlated to periods of capitalist crisis and reorganization.

Yet forms that comfortably rose with liberalism's long span are ones that become de-magnetized and lose influence when the social constellations and hegemony they were best fitted to serve begin to disintegrate. Here the long secular trend going back to the eighteenth century has been deflating for some decades. Indeed, for all the debates about neoliberalism's definition, one approach to the keyword is to see it as a movement that seeks to void liberalism's divisions between public and private and the line between citizenship and social death. The new phase of neoliberalization that emerged after the 2008 crash has massively amplified the loss of liberal culture, especially as algorithmic-based social networks and televisual streaming services have substantively broken away from liberalism's cultural regulation.12

As a result of this intermingling of secular and rhythmic temporalities, post-2008/11 prestige television differs from its earlier form that arose between the mid-late 1990s and 2008/11. Consequently, it has also broken away from its allegiance to the novel's disciplinary norms and all forms of "novel theory" designed to respond to and endorse the novel's significance. Today, prestige television looks to different cultural instruments, so as to both better ground itself among the shards of broken liberalism and propose alternative formations to liberal pluralist consensus.

3.

Lovecraft Country exemplifies this turn away from centrist liberalism by liberating itself from the novel as a form structured by the preoccupations of dominant, white America and its prejudices involving citizenship and segregation. The literary form that Lovecraft Country seeks to inhabit is akin to the emerging constellation of works motivated by speculative nostalgia, rather than a slightly prior mode of critical nostalgia.

Critical nostalgia often looks to dismantle dominant collective imaginaries by historicizing and demythologizing a sanitized memory. Speculative nostalgia operates differently than critical nostalgia in four key ways. First, the focus shifts from the (liberal) individual to the collectively experienced historical moment as a way of encouraging the consumer to see the construction of a social narrative and identity. Second, the look backwards is not to a lyrical wonder of a better or more innocent time, but to a history that is often tragic and passes its trauma onwards through the generations. Third, this mournful past is narrated not merely to record its events in order to seek justice by liberal authorities, but as a means for recombining society into a more politically aware and mobilized social collective greater than what was previously. Lastly, in this gesture, speculative nostalgia introduces forwards-looking alternatives, much like other modes of speculative, alternative lifeworld writing (so-called science fiction and fantasy) and rejects merely sequential plots of homogeneous time's passing. Thus speculative nostalgia often rejects novel theory's prior opposition between gritty social realism and romance, in favor of a combined and uneven development that mixes documentary newsreel or similar records of mass reportage with fantasia sequences and links period costume with contemporary dialogue, bodily comportment, and more diverse casting to depict what would have been historically segregated settings. Speculative nostalgia enacts Christina Sharpe's tripartite sense of being in the wake of historical tragedy, a post-burial social gathering meant to give testimony about the deceased, and a new political awareness (of being "woke").13

Recent instances of critical nostalgia (see below) seek to establish a new, intersectional left, where intersectionality is not meant to be confined to the unit of the complexly-formed individual, but as an experience-system of a variegated social collective that has come together through elective affinity and coalition-building, rather than pluralist consensus, since it does not seek to erase particular difference within the alliance. Lovecraft Country's speculative nostalgia likewise seeks to create a cross-generational, woke BIPOC collective that takes liberalism's equality claims to be as much of a problem as more crude racisms.

The first season stages the search for a magic codex by a patriarchal, white supremacist group that believes this project requires someone from their founder's bloodline, even if that carrier is the descendent of a Black slave. Their dual antagonists are Christina Braithwaite, the white daughter of a group's current leader, who is angry about the gender exclusions that deny her access, and the Freemans, an extended Black family, who ultimately search for magic as a way of taming their rage at structural racism's long duration and turning it into a creative and nurturing force. Braithwaite's agenda, however, is contained within liberalism's limits, since it seeks an individual's representational suffrage to become an active citizen and have access to educational training. The Freemans do not keep faith with liberalism's promises in ways exemplified by the show's two key lines: "I gotcha kid" and "You still haven't learned."14

The first involves how time-loops allow Atticus Freeman to protect his putative father from being killed decades earlier during the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The age inversion, where a now-adult child protects their juvenile parent, belongs to the show's commitment to inter-generational group care, not individual achievement. The second is the very last line of the season said by Diana Freeman, Atticus's niece, in response to an immobilized Braithwaite's call for help. While Braithwaite no longer presents a threat to the Freemans, who have succeeded in prohibiting the use of magic by "every white person in the world," Diana not only refuses to help but then snaps Christina's neck (in a seeming reversal of Eric Garner's fate and against the pun in the white family's name that suggests Black Americans should "wait" for their "breath" and not demand social change now). What Christina might have learned to save her life was said to her a few episodes earlier by Ruby Baptiste, as Ruby explains to Braithwaite why she could not bring herself to attend Emmett Till's funeral. Ruby says that she wants Braithwaite "to feel l what I feel right now. Heartbroken. Scared. Furious. Tired, so fucking tired, of feeling this way over and over, and I want you to feel alone and shameful. Because I'm here feeling this, and you'll never understand it. I want you to feel guilty for feeling safe [ . . . ] and your privilege."15

Yet what might initially seem Lovecraft Country's unexpected return to essentialist identity politics is less so in two ways. First, the overcoming of white liberal power results not from an autonomous and homogeneous Black community, but from a BIPOC coalition wherein different peoples of color "become one with the darkness" by overcoming their initial antagonism, having previously been pitted against one another (here Koreans and Black Americans), and combining their particular folkloric supernaturalism to confront white power. Here the "magical Negro" no longer serves white interests. In this sense, Lovecraft Country joins a host of other works that use Gothic, Horror, and the Weird to stage the construction of an intersectional BIPOC left, such as The Terror's season two, Penny Dreadful: City of Angels, and the graphic narrative by Emil Ferris, My Favorite Thing is Monsters.

Lovecraft Country belongs to the recent arrival of woke Weird tales that have transformed the assumed producers and consumers of genre narratives away from their assumed white, cis-male, and heterosexual audience towards one that is more BIPOC and sex-gender expansive.16 In the end, the "you" who will never learn is less an essentialized category than an epistemological one. The invitation to join "the darkness" is open to anyone who is willing to unthink liberalism's disciplinary formation and service to capital. Similarly, the new television looks to un-novel itself by abjuring the novel's prestige and disciplinary purpose and seeking instead to create tales for a post-liberal culture of a left intersectional collective.

Stephen Shapiro (@shapirostephen) is Professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies at the University of Warwick. His books include How to Read Marx's Capital (Pluto, 2008), The Culture and Commerce of the Early American Novel: Reading the Atlantic World-System (Penn State University Press, 2008), The Wire: Race, Class, and Genre, with Liam Kennedy (University of Michigan Press, 2012), and Pentecostal Modernism: Lovecraft, Los Angeles, and World-Systems Culture, with Philip Barnard (Bloomsbury, 2017).

References

- On speculative nostalgia, see Stephen Shapiro, "Speculative Nostalgia and Media of the New Intersectional Left: My Favorite Thing is Monsters," in The Novel as Network: Forms, Ideas, Commodities, edited by Tim Lanzendörfer and Corinna Norrick-Rühl (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 119-36.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 1, "Sundown," directed by Misha Green, aired August 16, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- Langston Hughes, "Harlem," in The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersand (New York: Vintage, 1995), 426.[⤒]

- David Lavery, "This Thing of Ours," New York Times, September 15, 2002. [⤒]

- The Wire, season 5, episode 9, "The Dickensian Aspect," directed by Seith Mann, aired February 10, 2008, on HBO.[⤒]

- See Immanuel Wallerstein, After Liberalism (New York: The New Press, 1995); Liam Kennedy and Stephen Shapiro, introduction to Neoliberalism and Contemporary American Literature, edited by Liam Kennedy and Stephen Shapiro (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2019), 1-21; Sharae Deckard and Stephen Shapiro, "World Literature and the Neoliberal World-System," in World Literature, Neoliberalism, and the Culture of Discontent, edited by Sharae Deckard and Stephen Shapiro (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 1-48. For a discussion of the difference between secular trends and rhythmic cycles, see Immanuel Wallerstein, "Typologies of Crises in the World-System," in Geopolitics and Geoculture: Essay on the Changing World-System (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991), 104-122.[⤒]

- Karl Marx, Economic Manuscript of 1861-63, in Marx and Engels Collected Works, Vol. 34. (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 2010), 327; Immanuel Wallerstein, "The End of What Modernity?" in After Liberalism, 129; Wallerstein, "The French Revolution as a World-Historical Event," in Unthinking Social Science: The Limits of Nineteenth-Century Paradigms, 2nd edition (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2001), 13.[⤒]

- Wallerstein, "The French Revolution," 7-22; Wallerstein, "Three Ideologies or One? The Pseudobattle of Modernity," in After Liberalism, 72-92.[⤒]

- Wallerstein, The Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789-1914 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 146.[⤒]

- See Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. (London, Verso: 1983[⤒]

- Michel Foucault, "Society Must be Defended": Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976 (New York: Picador, 2003), 175.[⤒]

- Stephen Shapiro, "Foucault, Neoliberalism, Algorithmic Governmentality and the Loss of Liberal Culture," in Kennedy and Shapiro, 43-72.[⤒]

- See Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2016).[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 10,"Full Circle," directed by Nelson McCormick, aired October 18, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- Lovecraft Country, season 1, episode 8, "Jig-a-Bobo," directed by Misha Green, aired October 4, 2020, on HBO.[⤒]

- Stephen Shapiro, "Woke Weird and the Cultural Politics of Camp Transformation," in The American Weird: Concept and Medium, edited by Julius Greve and Florian Zappe (London: Bloomsbury, 2021) 55-71.[⤒]