Ali Smith Now

"Which game would you rather play? I'll give you a choice of two. One. Every picture tells a story. Two. Every story tells a picture."1 So proposes Daniel Gluck to eleven-year-old Elisabeth Demand early in their friendship. The choice Elisabeth makes will determine the course of their game, even, in some ways, the course of her future professional life. But these aren't mutually exclusive possibilities, as Daniel's framing makes clear. What he proffers is a pair of equally valid propositions, enabling conditions for their game — and for Ali Smith's Seasonal Quartet, too, which often serves up ars poetica axioms of this kind. In each of the four novels, Smith tells her readers a picture (or a sculpture or a drawing or a film) by foregrounding the work of a woman artist: Pop painter and collagiste Pauline Boty in Autumn, abstract modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth in Winter, contemporary filmmaker and landscape drawing artist Tacita Dean in Spring, and filmmaker-painter-novelist Lorenza Mazzetti in Summer. And even as each novel acquaints us with their (often overlooked or underappreciated) work through extended, careful visual description, so too do the pictures that Smith summons tell stories of their own, about how to "comprehend" an avalanche, combat the male gaze, cradle a child.2

The Seasonal Quartet brings pictures and stories into necessary relation with each other. In Daniel's proposal to Elisabeth, that necessity is underscored by Smith's chiasmus, which is not just a repetition or a reversal but also a figure for "reciprocal exchange."3 Pictures and stories are mutually dependent, capable of acting upon each other or calling each other forth. And Smith's insistence on intermedial reciprocity is noteworthy within the context of the longer history of ekphrasis, the rhetorical mode that is obviously at issue, since Daniel proposes to describe a collage so that he and Elisabeth may see it "in the memory" and "in the imagination."4 Usually defined as "the verbal representation of visual representation" and typified by writings like John Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn," ekphrasis has often been characterized as a contest between writer and painter for superiority.5 Understood this way, ekphrasis is a rhetorical mode steeped in the power imbalance that obtains across lines of difference. Take, for instance, W. J. T. Mitchell's powerful account of ekphrasis as an "ambivalence" about otherness, linked to other kinds of "political, disciplinary, or cultural domination," especially gendered domination: in his view, ekphrasis makes clear that representation is "something done to something, with something, by someone, for someone."6 But domination is hardly the only impulse that animates ekphrasis, as Brian Glavey has argued: "Ekphrasis is not simply about seeing; it is also about showing and sharing. It is, in this sense, pedagogical. Queer ekphrasis in particular is dedicated to the proliferation of an unpredictable spectrum of relationality, multiplying ways of desiring, identifying with, attaching to, loving, imitating, envying, and sometimes ignoring works of art."7 Ekphrasis is fundamentally relational, then, but broadly and variously so. Even as a writer's description of a painting can sometimes constitute a bid for artistic supremacy, it may just as well operate more like the title of Smith's newest novel, Companion Piece: ekphrasis can accompany, stand beside, and also instantiate friendship, as it does for Daniel and Elisabeth.

Companionate pedagogy is very much the mode of their game and their relationship. After Daniel describes a collage by Pauline Boty — Untitled (with lace and hair colour advert), from 1960 or 1961 — he realizes that it's time for his walk with Elisabeth to end and he looks at his watch: "Come on, art student, he said. Pupil of my eye. Time to go."8 Daniel is teaching Elisabeth how to see — and by extension, how to see as Pauline Boty saw. As he notes at a different point, he fell in love with the way Boty saw the world: "It is possible, he said, to be in love not with someone but with their eyes. I mean, with how eyes that aren't yours let you see where you are, who you are."9 Daniel passes this sight along to Elisabeth. And there's more: Elisabeth the pupil also enables Daniel's sight, by functioning like the opening in the iris that permits light to strike the retina. Smith's wordplay, charted by Charlotte Terrell in this cluster, here underscores the reciprocity of their visual relationship: Daniel's pupil learns to see as he does, and Daniel's pupil allows him to see. This latter dynamic becomes especially important near the end of the Quartet, in a scene from Summer that flips their roles from Autumn. Now an adult and a teacher herself, Elisabeth has just returned from a day trip to Siena with her students to visit the fourteenth-century frescoes of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Allegory of Good and Bad Government. "Tell me one of the pictures," Daniel says, "from memory."10 So Elisabeth forgoes the photos on her phone in favor of patient ekphrasis, telling Daniel the picture of good governance: "bright architecture under a night sky," "sweet communal living," and "people working, writing, making things," "holding on to each other" in a "peaceful city" where "summer has come."11

Not coincidentally, Daniel and Elisabeth both describe fragile, inaccessible objects. Pauline Boty's collage has disappeared. Lorenzetti's frescoes are unevenly preserved, nearly seven hundred years old, and a thousand miles away from Daniel. Smith's ekphrases "insist that art and experience must be communicated so as not to be lost," and in this way they evince the same commitment to the relatability and "sociability of art" that Glavey finds in Frank O'Hara's poetry.12 Ekphrasis proves so sociable, in fact, that it becomes a mode of flirtation: visual description, especially of William Blake's Beatrice Addressing Dante from the Car (1824-27), gets Daniel's romance with Sophia Cleves underway in 1978. After their first meeting, she swoons over having met a man "who sensed that she has feelings and who bowed to them, who has looked at her through holly leaves and described all sorts of things to her, described art, poems, theatre, described the green dress of hope."13 Just as it is elsewhere in the Quartet, description is here an act of connection and care, a mode of paying attention, and a kind of love, not just for the art object or artist but also for the listener.

This is a way of seeing, showing, and sharing that Smith has learned from John Berger, who suggests, in her words, "that the aesthetic act, that art itself, is always collaborative, always in dialogue, or multilogue, a communal act."14 Smith might even be said to imagine an art world that overturns the commodity and ownership logics that Berger identifies as structuring "the way of seeing invented by oil painting," in which a painting is "not so much a framed window open on to the world as a safe let into the wall, a safe in which the visible has been deposited."15 Ekphrasis broadly — especially artistic description from memory of the kind that Daniel and Elisabeth practice — is a practice of non-ownership, non-possession. Rather than "spectator-owners" or "spectator-buyers," Smith features imaginer-sharers, who look and remember, tell pictures and listen, and allow for us to become reader-sharers, too.16 This is a profoundly generous way of seeing — hospitable would be Berger's preferred term, and Smith's too, perhaps, since she echoes Berger's concern for refugees and their kin, the uninvited strangers to whom Matthew Hart draws our attention. If, as Smith says, "the act of going beyond ourselves is the art act," then the action of ekphrasis, the work that art does, is to counter solipsism and isolation by putting us into relation with other people.17

This is true even of the one important privately owned art object in the Seasonal Quartet: Daniel Gluck's two-part Barbara Hepworth sculpture. "A mother and child pairing," the sculpture has been separated so that Daniel has the larger "stone with the hole through the middle of it," and Sophia Cleves has the small, "weighty," "pale red-brown" stone in her wardrobe.18 Summer reunites these two parts, as Sophia's son Art brings the small child stone — his "memento mori," found among his dead mother's possessions — to Daniel in Suffolk.19 The journey makes the sculpture whole, restoring it to and for its owner. But the reunion is haunted by absences. Sophia, the mother, has died. Neither the child, Art, nor the father, Daniel, knows that they are related. The whole is "full of holes," then, but these absent relations become the grounds for new ones, too, as Art falls in love with Elisabeth Demand.20

Many of the most poignant art acts in the Seasonal Quartet are similarly familial, involving parents and absent children. Richard Lease's postcard correspondence with his friend Paddy is also a way of inventing a relationship with his daughter, whom he hasn't seen since her very early childhood.21 Richard pretends to "take her to see things" and meet her "imaginatively" at art exhibitions, and then he writes Paddy postcards in her voice.22 Ending each with "wish you were here," Richard conjures not just Paddy's presence but also his daughter's.23 As Amy Elkins and Deidre Lynch remind us, "picture postcards exist in a complicated relationship to presence," not least because they are also "potent emblems of contingency." Smith trades on such contingency — now "articulated" not to a picture postcard but to a gargantuan picture — when Richard visits a Tacita Dean exhibition.24 Confronted by the "terrible" sublimity of the mountain avalanche in The Montafon Letter (2017), Richard says "fuck me" out loud, and the young woman beside him cosigns the sentiment, saying "fuck me too."25 I can't help but read the scene as a chance meeting between father and daughter — the inverse of the meeting between Rainer Maria Rilke and Katherine Mansfield that never takes place. Just barely, just for "half a minute," Richard stands in the presence of young woman who isn't merely very like Elisabeth Demand but perhaps Elisabeth Demand herself, with her track record of effusive reactions to "arty art" that "you can't write [...] in a dissertation."26

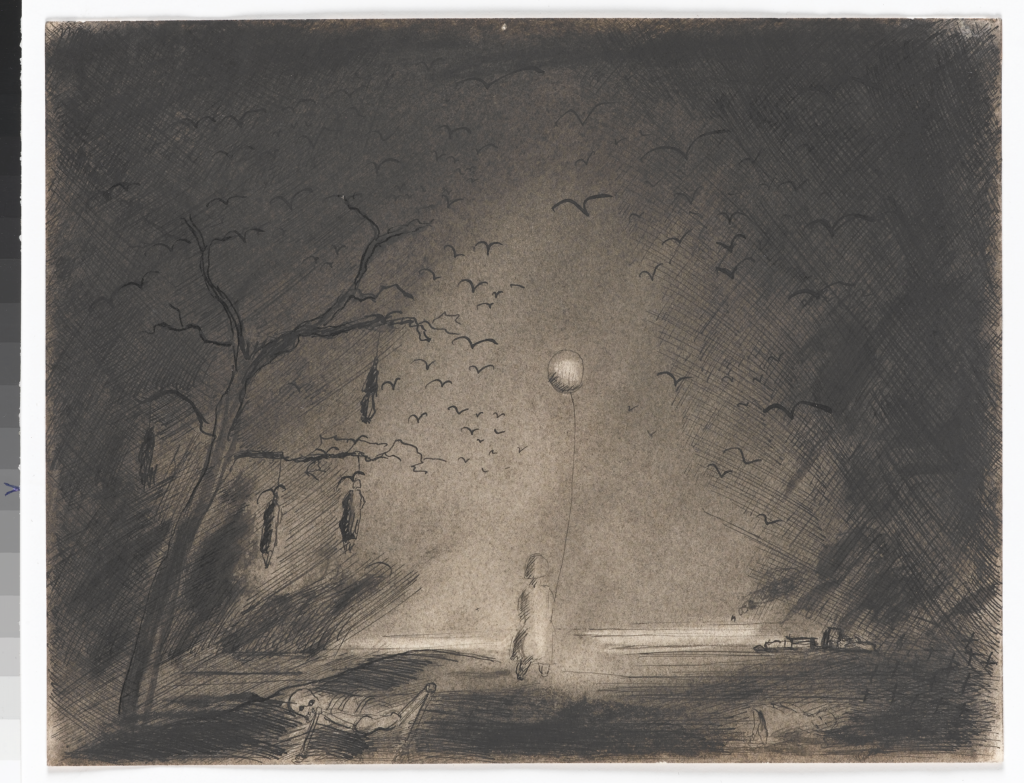

If Smith often separates families in the Quartet, she also regularly transmutes fathers' forestalled vision of the children that they can't see into compensatory acts of looking at art. In Summer, Fred Uhlman follows this impulse one step further. We meet Uhlman, a Jewish German-English artist, in the flashback scenes about Daniel's internment on the Isle of Man, where Uhlman really was imprisoned during World War II, just before the birth of his daughter.27 Confined thus, Uhlman drew pictures "dedicated to his new born child" that feature "a small girl holding a balloon bobbing on a string [...] walking through hell" (see Figure 1).28

For both the real and the fictionalized Uhlman, these drawings establish a father's imaginative relation to a daughter he hasn't met. His parental conjuring is more desperate and ambitious than Richard's: with only pen and paper, Uhlman attempts to manifest safe passage for his daughter through the Blitz and through xenophobia, so that "the horror doesn't touch her."29 Like Florence Smith in Spring, the ink-drawn girl child "walks about, curious, detached, untouched, and just as powerful as — increasingly more powerful, as the drawings multiply, than — any of the hellish things happening round her."30 Like art-viewing and art-describing, then, art-making in the Quartet is tender and intimate, and sometimes survivalist — charged not just with the weight of human relations but also with the grave purpose of helping people to navigate the world.

Given the larger visual dynamics of these novels, in which more sinister scopic regimes constantly threaten to take hold, Smith's commitment to exceed mere seeing, to make artwork the generator of a "reparative sociability," is all the more remarkable.31 To be sure, Pauline Boty offers a way of seeing for Daniel and Elisabeth. Likewise in love with Boty's eyes, Smith concludes Autumn by prompting our attention toward her favored flowers: "There's a wide-open rose, still. Look at the colour of it."32 But there's more, as Berger tells us: "a way of looking at the world implies a certain relationship with the world, and every relationship implies action."33 If a wide-open English rose still exists, the UK can act to welcome refugees hospitably. This is a way to repair the world — or, as Pamela Thurschwell puts it, to make amends.

Reading Smith's work, to echo what she has said of Berger, means encountering her insistence that "a better world" is not "fantasy or imaginary": it is "impetus — possible, feasible, urgent and clear."34 Firmly situated in the present, the Seasonal Quartet doesn't suggest that "another world is possible" but rather that "this world, if we look differently, and respond differently, [is] differently possible."35 The other artists featured in the Quartet add to our repertoire of responses, our ways of inhabiting and interacting with the world. Bagging air from a balloon over the Alps and chalking clouds onto slate, Tacita Dean gives us a way of breathing. Barbara Hepworth summons the tactile, the embodied response, as Sophia presses the round stone to her face and Art "enjoy[s] feeling the weight of it."36 The sculptor gives us a way of connecting, a way of holding, and holding on. Writing, painting, and making films in the wake of the brutal Nazi murders of her family, Lorenza Mazzetti gives us a way of mourning and surviving, a way of "crossing the rubble" and grappling with the juxtaposition of the "everyday and the near-apocalyptic."37 More than just reactions to art, these are ways of being in the world and acting in it, because in our fragile present, seeing, showing, and sharing are not quite enough.

Cara L. Lewis (@carallewis) is Associate Professor of English and affiliated faculty in Women's and Gender Studies at Indiana University Northwest. She is the author of Dynamic Form: How Intermediality Made Modernism (Cornell University Press, 2020).

References

- Ali Smith, Autumn (New York: Anchor Books, 2017), 72.[⤒]

- Ali Smith, Spring (New York: Anchor Books, 2020), 78.[⤒]

- T. V. F. Brogan, A. W. Halsall, and W. Hunter, "Chiasmus," in The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, edited by Roland Green, Stephen Cushman, and Clare Cavanagh, 4th ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), http://proxynw.uits.iu.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/prpoetry/chiasmus/0?institutionId=2981.[⤒]

- Smith, Autumn, 72.[⤒]

- James A. W. Heffernan, Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 3.[⤒]

- W. J. T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 156-57, 180.[⤒]

- Brian Glavey, The Wallflower Avant-Garde: Modernism, Sexuality, and Queer Ekphrasis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 6.[⤒]

- Smith, Autumn, 75.[⤒]

- Smith, Autumn, 159-60.[⤒]

- Ali Smith, Summer (New York: Anchor Books, 2021), 159.[⤒]

- Smith, Summer, 159-160.[⤒]

- Brian Glavey, "Having a Coke with You Is Even More Fun Than Ideology Critique," PMLA 134, no. 5 (2019): 998, 1004.[⤒]

- Ali Smith, Winter (New York: Anchor Books, 2018), 266.[⤒]

- Ali Smith, "A Gift for John Berger," Verso Books (blog), December 6, 2018, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2923-a-gift-for-john-berger-by-ali-smith.[⤒]

- John Berger, Ways of Seeing (New York: Penguin, 1977), 109.[⤒]

- Berger, Ways of Seeing, 101, 134.[⤒]

- Smith, "A Gift for John Berger."[⤒]

- Smith, Autumn, 44, and Winter, 267.[⤒]

- Smith,Summer, 106.[⤒]

- Smith, Winter, 273.[⤒]

- If my math is right, Richard hasn't seen his daughter—who is named Elisabeth, uses a different surname from his, and must surely be Elisabeth Demand—since she was two or three. When we meet Elisabeth Demand in Autumn, in the summer of 2016, she is thirty-two years old, and several chapter openings give us enough data points to conclude that Elisabeth was likely born in late spring 1984, probably in May (Autumn 67, 115, 149). This information coincides with Richard's acknowledgement in Spring that he last saw his daughter "in the year 1987" and his sense that she would now be about the age of the young woman at the Tacita Dean exhibition (289).[⤒]

- Smith, Spring, 74-75.[⤒]

- Smith, Spring, 79.[⤒]

- Articulation, as Berger points out, "implies both the act of joining and the act of changing direction." John Berger, "Martin Noel," in Portraits: John Berger on Artists, ed. Tom Overton (New York: Verso, 2017), 479.[⤒]

- Smith, Spring, 78.[⤒]

- Smith, Spring, 289; Autumn, 229; and Autumn, 224.[⤒]

- Hutchinson Camp on the Isle of Man was known as the artists' camp, and the "notorious" artist Kurt "who barks like a dog" in Smith's novel can be none other than Kurt Schwitters. See Smith, Summer, 175.[⤒]

- Smith, Summer, 173.[⤒]

- Smith, Summer, 173.[⤒]

- Smith, Summer, 173.[⤒]

- Glavey, "Having a Coke with You," 999. By proliferating ways of seeing with distinct affordances, the Seasonal Quartet follows on the visual multiplicity of How to be both, which I've written about elsewhere. Cara L. Lewis, "Beholding: Visuality and Postcritical Reading in Ali Smith's How to be both," Journal of Modern Literature 42, no. 3 (2019): 129-150, https://doi.org/10.2979/jmodelite.42.3.08.[⤒]

- Smith, Autumn, 260.[⤒]

- John Berger, "The Ideal Critic and the Fighting Critic," in Landscapes: John Berger on Art, ed. Tom Overton (New York: Verso, 2018), 97.[⤒]

- Geoff Dyer, Olivia Laing, Ali Smith, and Simon McBurney, "John Berger Remembered," The Guardian, January 6, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jan/06/john-berger-remembered-by-geoff-dyer-olivia-laing-and-ali-smith.[⤒]

- Dyer et al., "John Berger Remembered."[⤒]

- Smith, Summer, 107.[⤒]

- Smith, Summer, 255, 261.[⤒]