Bored As Hell

In the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, an aristocratic, worldly mode of resignation yielded to bourgeois withdrawal into the "interior" — literally, of the home and, figuratively, of the self. Through this discursive shift from public mourning to private suffering, from collective to individual forms of malaise . . . a modern conception of subjectivity came into being.

— Elizabeth Goodstein, Experience without Qualities1

The first days of the pandemic were sharp with a sense of danger. Boredom seemed impossible. I felt as if my actions counted, as if my choices during this moment of historical fissure were freighted with significance. The feeling soon wore off. The long hours in my apartment turned flat and stale.

As it became clear that the lockdowns would last for months if not years, I found myself drawn, first desultorily, then with increasing hunger, to stories of bored and lonely housewives. Above all, I turned to Chekhov, whose plays are filled with people complaining about their boredom. Drama supplied a social landscape I was missing, a chorus of voices, the charm and twist of conversation. And Chekhov's theater turned boredom from an inchoate private feeling into a spectacular display.

Beautiful Yelena stalks through Uncle Vanya (1898) like a wraith, agonized by her boredom — "too indolent to live," Vanya remarks.2 She is married to an old professor who spends his days burrowing into scholarship. His labors are pointless, the play suggests; but at least he has his work. Yelena understands there is noble work to be done, but she cannot imagine doing it. "Only in idealistic novels," she says, "do people teach and doctor the peasants" (203). Swaying with indolence, she is the most conspicuous figure in Chekhov's parade of empty lives.

Observing Yelena's contagious idleness, Sonya, the play's voice of moral goodness, proposes a remedy for existential malaise: ceaseless work in service of others, "without ever knowing rest" (230).3 Her solution to the emptiness of existence is a life of submissive toil followed, in heaven, by holy idleness. "We shall rest!" Sonya cries at the play's end, kneeling before Vanya, eyes shining, imagining the peaceful world to come. As the curtain falls, she repeats: "We shall rest! We shall rest!" The prayer-like intonation acknowledges the potential glory of inactivity. But stasis in this life, the play warns, can only ever be laced with anguish.

*

It is hard to read Chekhov without thinking of what came swiftly after his death: the collapse of the bourgeois milieu whose quiet griefs he depicts so truthfully. "[M]any of the artists who matter most in the twentieth century," writes the art historian T. J. Clark, "lived instinctively within the limits of bourgeois society, but . . . they felt this society was coming to an end."4 Modernism is in large part the story of artists coping with the dissolution of bourgeois society in the face of the violence of the twentieth century, especially that of the First World War. The case of Picasso is characteristic. For Picasso, the nineteenth-century social order in which he was raised found symbolic expression in "the space of a small or middle-sized room and the little possessions laid out on its table."5 His Cubist still lifes pay tribute to this world of interiors, finding infinite refracted complexity within private room-bound existence and the display of objects on a table (Fig. 1). As the twentieth century calamitously wore on, the geography of his imagination changed. No more could a cozy well-furnished room, the backdrop of middle-class life and conduct, stand for an entire civilization.

The two works I focus on in what follows — Henrik Ibsen's Hedda Gabler (1890)and Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) — show what happens when the middle-class interior becomes a trap. These works, very different from each other in their scope, aims, context, and aesthetic form, imagine the bored housewife as the figure on whom the maintenance and future of middle-class existence depends. Both texts stage the duality articulated in Uncle Vanya between submissive work and agonized idleness. And both erupt, at the end, into violence: the bored housewife's revolt is imaginatively felt to usher in the collapse of bourgeois civilization.

*

Boredom is a state of detachment. It involves an inability, or an unwillingness, to engage with the objects in one's immediate reality and find them interesting or meaningful. Why detach? In certain cases, boredom could arise if the bored person has not received the appropriate training to appreciate the object or situation they find boring. (Imagine my stuttering dismay when a class of students informed me that they found Middlemarch dull.) Such boredom is, in theory, correctible. Nothing is boring to the mind of God: a supremely cultivated intelligence can find interest and value in any phenomenon, no matter how minor.

But we are not gods; as mortals with one precarious life, we are conscious of when our time is being wasted. So we must reckon with a more intractable, and illuminating, form of boredom. This is the boredom provoked when one's environment is so narrow or stupid or coarse that to submit to it — to agree to find it engaging or worthwhile — would feel false, even degrading. This kind of "existential" boredom is linked not simply to criticality but to a posture of superiority. It is a protest that we are meant for something better. Ibsen's Hedda Gabler is bored in just this way.

Ibsen begins Hedda Gabler with extensive stage directions describing the drawing room in which virtually the entire action of the play takes place. The room, "well furnished" and "in good taste," epitomizes middle-class comfort and propriety.6 This bourgeois interior is also a cage. The first thing Miss Tesman, the doting aunt of Hedda's scholar-husband, does upon entering is throw open the glass doors on the left, a gesture that makes us aware of the home as an enclosure. In the back wall of the drawing room is a doorway leading into another, smaller room "decorated in the same style" (263). The effect is of a mise en abyme that visually captures Hedda's narrowing of possibility: bourgeois life leads to nothing but more of the same, just smaller. A portrait of Hedda's father, a decorated general, hangs in that inner room, overseeing the play's proceedings. Later, Hedda's piano will be moved there as well. It is here, in this back room, amid these discarded icons of aristocracy and self-expression, where at the end of the play Hedda will shoot herself.7

Hedda is newly married to Jörgen Tesman, an affable but oblivious scholar who is gushed over so effusively by his aunt in the play's first moments that when Hedda enters the drawing room at last, her deflationary attitude is felt as a needed corrective. She refuses to feign interest, for example, in the pair of old slippers his aunt has lovingly delivered. Nor does she pretend to be anything but bored by the book project for which Tesman spent their honeymoon compiling notes. Ibsen takes pains to establish Hedda's palpable boredom as reasonable. He aligns the reader/viewer with Hedda by emphasizing Tesman's slowness of uptake in conversation, and by selecting for Tesman's research a topic so sterile and soporific — domestic crafts in Brabant in the Middle Ages — that it seems designed to make us yawn.

Is Hedda's problem simply that she has married badly? That she is isolated in a house in the countryside with nothing to do but bear children for a dry antiquarian? No, her boredom has deeper roots. Hedda is no study in false consciousness. She has a clear sense of her place in the gender system and class structure of her society. She curses "this middle-class world that I've got into" (306). She complains to Judge Brack about the intrinsic monotony of marriage. Brack, a figure of the established order in all its hypocrisy, proposes to relieve her boredom by making the marriage into a triangle.

Yet neither personal factors (the dullness of Tesman and his scholarship) nor structural forces (the expectations of marriage, the limited opportunities available to women) adequately explain Hedda's boredom. When questioned by Judge Brack, she struggles to think of a single object that could fascinate her. She reflects: "It often seems that I've only got a gift for one thing in the world. [...] For boring myself to death" (307). Her boredom seems dispositional and deeply embedded. While bourgeois housewifery strikes Hedda as particularly intolerable, it is doubtful that any conditions could satisfy her.

The domestic existence that spells tranquility for Tesman, tedium for Hedda, is soon disrupted. The news arrives that Ejlert Lövborg — Hedda's old lover, and a potential rival for Tesman's position at the university — is back in town. So is Thea Elvsted, a former schoolmate of Hedda's, now Lövborg's collaborator, lover, and muse. Aided by Thea, Lövborg has published a brilliant book and prepared the manuscript for a greater work to come. But Thea fears that back in the city, he will lapse into his old, dissolute habits and fall into scandal, or drink himself to death.

Boredom, remarks Patricia Meyer Spacks, is often a "creative impetus."8 Indeed, boredom serves as a prompt to action. But its alliance with creation is less certain. Out of Hedda's boredom springs sheer destruction.9 The contrast Ibsen develops between Thea and Hedda makes this point clear. Thea—fragile, wispy, and easily frightened—represents the workings of inspiration. Hedda, associated with fire, embodies the countervailing forces of destruction. She easily dominates weepy, trusting Thea—pushing her into chairs, pinching her arm, threatening to burn off her pretty hair. Yet Thea, far from being insubstantial, has achieved everything Hedda longs for. She has exited a dull marriage and guided Lövborg toward the realization of his genius. All this work, painstakingly done by Thea, is undone by Hedda. Hedda provokes Lövborg into drinking, burns his new manuscript, and presses on him the pistol that will kill him. He will not die of a noble suicide, as Hedda envisions. Instead, he will shoot himself in the stomach in a brothel.

Thea evades the boredom of housewifery by finding an object that fascinates her: serving as an adjunct to Lövborg's projects. Recall Chekhov's Sonya: "we'll work for others . . . without ever knowing rest" (230) — yet Thea's work, we feel, is more nourishing . After Lövborg's death, Tesman joins this task. He pledges to devote himself to reconstructing his dead rival's destroyed manuscript, working from notes Thea has saved. The job suits his modest talents. "Arranging and collecting," his aunt remarks in the first scene, "that's what you're so good at" (Ibsen 272). One of the last images in the play is of Tesman and Thea coupled, their heads bent together over the writing table. Together they have taken the role Hedda could have played — as wife, or widow, to Lövborg's genius. Hedda's first creative act is also her last. She shoots herself in the temple: the noble suicide she had imagined for Lövborg. The line from Judge Brack that ends the play — "One doesn't do that kind of thing!"— picks up a refrain heard several times earlier in the play's examination of bourgeois manners (364). This final repetition laces the tragic denouement with black comedy. The judge's exclamation is the cry of the bourgeois order protesting its own annihilation. Hedda, however, had already warned him. She told him she was bored to death.

*

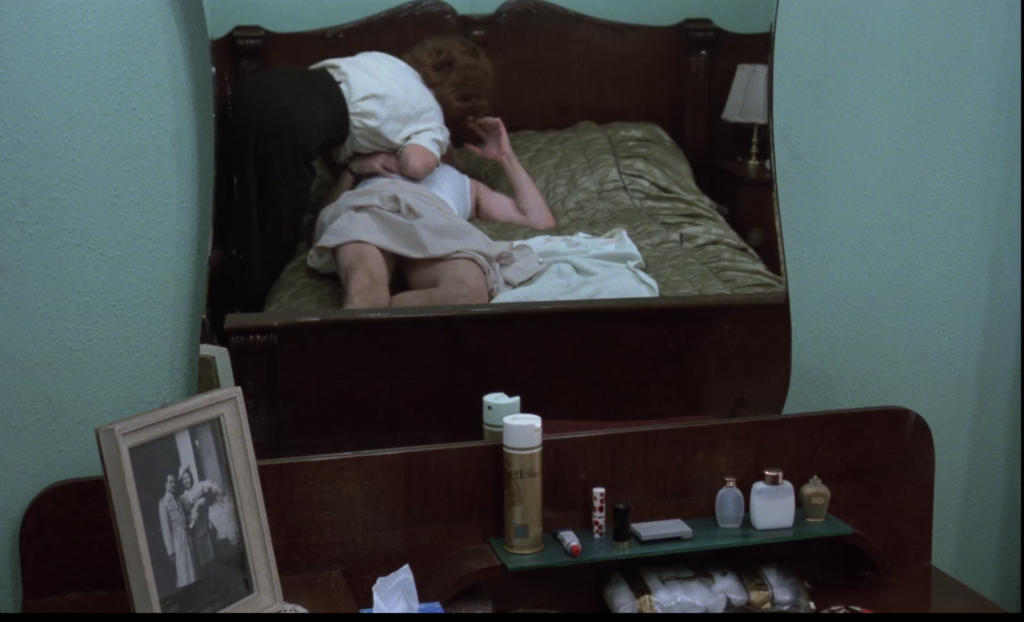

Jeanne Dielman follows three days in the life of Jeanne, a widow and mother in Brussels. We watch her perform, in real time, a series of household chores: peeling potatoes, brushing shoes, making coffee, scrubbing the bathtub (Fig. 2). She is also a prostitute, and she has integrated her sex work into her rotation of daily chores. In the film's first scene we watch her put potatoes on the stove just before her client arrives; after they finish in the bedroom, she takes the potatoes off the boil. The sense one gets is of a precariously balanced routine compulsively maintained.

Although cinephiles think of Jeanne as an archetypal housewife, as a widow she is, strictly speaking, not a housewife at all. She is, rather, a house-wife: married, in effect, to her home, absorbed in the domestic space which she looks after so dutifully. Yet if her housekeeping is a labor of love, it is a non-reciprocal romance. The effect of making Jeanne a widow is to reduce her to her labor functions while isolating her. As prostitute, she plays the role of "wife," responsible for male sexual gratification in addition to cooking and cleaning. Although her son is well into his teenage years, she occasionally looks after a neighbor's howling infant. Thus, in her small flat, she undergoes every familiar trial of housewifery.

In Akerman's study of stasis, the camera never moves: the film consists of long static takes in which Jeanne moves in and out of frame, smoothing down the bed, washing dishes, breading veal. Many shots begin in media res, with Jeanne engrossed in a new task. Activities such as eating or bathing or brushing her hair are treated as continuous with the chores, and so these tasks of self-maintenance come to seem like labor. A scene in which the son attempts to memorize a Baudelaire poem and recites it twice, making different mistakes each time, underscores the film's sense of life lived by rote with only minute variation.

Clinical, even ethological, in its precision, Jeanne Dielman observes these menial rituals at such great length — the film runs 3 hours, 18 minutes — that we grow attuned to the most minor deviations from the heroine's established patterns. By the film's second half, when errors introduce themselves into her routine — a fork falls, a shoe drops, her typical seat in the café is taken — our attention has been so enlarged, the details so magnified, that we are able to detect the breakdown of the machine. The film "demands total attention," a New York Times reviewer commented. "If one gives it anything less its revenge will be a boredom so complete it might be fatal."10 Indeed, fatal boredom is the film's true subject: the climax is Jeanne's murder of a client with a pair of scissors.

Akerman's methods of shooting and framing work to attenuate, though not entirely dispel, the audience's identification with the heroine. There are no close-ups. The fixed camera observes Jeanne in medium and long shots. Akerman deprives us of any careful study of the face. Jeanne begins the film with her back turned, and in the hours that follow she remains elusive.

Jeanne Dielman recalls Picasso's Cubism in its discovery of infinite complexity within a mundane bourgeois interior, its reliance on still-life compositions of objects on a table, and the rewards it offers to sustained looking. Unlike Picasso, however, the film commits itself to the bare representation of reality. There are no montages or zoom shots or expressionist bursts of color; any disclosure of personality is conveyed through external objects alone. We infer Jeanne's dissatisfaction, for example, when she makes coffee, tastes it, pours it out, grinds beans for a new batch, and then watches the coffee seep slowly through the hourglass-shaped filter in one of the film's most poignant images of time passing.11

If Uncle Vanya and Hedda Gabler each present a pair of women, one of whom is allied with submissive labor (Sonya, Thea), the other with agonized idleness (Yelena, Hedda), then in Jeanne these two types are condensed. The Jeanne of the film's first half is a figure of mechanical, compulsive industry. But later, as her cycle of rituals starts to crumble, we are given scenes of inaction rather than labor. In one sequence near the end, we watch Jeanne for several minutes sitting in a chair, inert, as if in a fugue state (Fig. 3). At first, she sits in the more distant armchair (we notice the empty seat close to the camera); then, after the neighbor's baby is brought in, she switches chairs and becomes more alert (Fig. 4). The medium of film allows us to perceive the heroine's boredom as not just a cognitive-affective but a fully embodied state.12

The film tells us several times that Jeanne is missing a double, that she is one half of a pair. There is her dead husband, of whom the empty chair reminds us. There is also her sister, who has emigrated to Canada, where her situation curiously parallels Jeanne's: "I hardly get out," she reports in a letter; "I'm at home most of the time." In the kitchen where Jeanne spends countless hours, there is sometimes one chair, sometimes two. There is, at last, a doubling within Jeanne herself: the frenetic Jeanne of the film's first half and the catatonic Jeanne of the late scenes, in which she succumbs to the emptiness of her existence.

Multiple shots of Jeanne reflected in mirrors emphasize this theme of splitting or doubling. One repeated mirror shot shows Jeanne ascending in the elevator to her apartment. It is the film's most vivid image of confinement (Fig. 5). Multiple visual elements underscore Jeanne's constriction. She is framed by mirror, elevator, and wall panels. The bars of the elevator resemble the bars of a cage. Her reflection is incomplete, split in two.

When in the film's final ten minutes Jeanne seizes a pair of scissors and drives them into the neck of the client she has just slept with (and with whom she has achieved an orgasm), that action, too, is depicted in a mirror. The shot of the murder gives us two images of Jeanne (Fig. 6). Both images are doubly mediated. First, we see her reflected from behind in the mirror. Second, we see a frontal view, in a photograph just barely visible on the table. The photograph presumably depicts her with her dead husband, who, like the john, appears to have a dark moustache.

Scholars have debated the eruption of violence at the end of Jeanne Dielman, interpreting this disturbance as stemming from repressed sexuality, or exemplifying the threat of randomness in a film in which the most mundane events are subjected to strict regulation. What is clear is that the order of Jeanne's life, the series of rituals once automatically followed — the metabolic labor that underpins bourgeois existence — has come undone. As with Hedda Gabler, the bored housewife's violent refusal spells the end of a certain way of life.

Both Hedda Gabler and Jeanne Dielman see the middle-class housewife as caught in a polarity between submissive work and empty idleness. Who would not revolt, given these alternatives? Such conditions not only engender boredom; they also block agency, making an autonomous human life impossible. These works test the idea that the fate of bourgeois civilization depends on the housewife's assent to boredom, to monotonous and repetitive room-bound existence. Such a demand is unsustainable. And so these works warn: boredom ends in blood.

Charlie Tyson (@CharlieTyson1) is a PhD student in English literature at Harvard. He is writing a dissertation about literary depictions of idleness from the late nineteenth century to the present.

References

- Elizabeth Goodstein, Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 98.[⤒]

- Anton Chekhov, Uncle Vanya, in The Major Plays, translated by Ann Dunigan (New York: Signet, 1964), 184. All further references come from this edition and will be given parenthetically in the text.[⤒]

- Sonya tells Yelena: "boredom and idleness are catching" — a reflection of Chekhov's understanding of boredom as a pathology requiring diagnosis (203). See Elizabeth M. Phillips, "Chekhov, Boredom, and Pathology as Dramatic Technique," Modern Drama 63, no. 1 (Spring 2020): 39-62.[⤒]

- T. J. Clark, Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 18.[⤒]

- Clark, Picasso and Truth, 17.[⤒]

- Henrik Ibsen, Hedda Gabler, in Hedda Gabler and Other Plays, translated by Una Ellis-Fermor (London: Penguin, 1961), 263. All further references come from this edition and will be given parenthetically in the text.[⤒]

- This back room, argues Susan L. Feagin, is a "non-place," reflecting the emptiness of Hedda's quest for freedom. "Where Hedda Dies," in Ibsen's Hedda Gabler: Philosophical Perspectives, ed. Kristin Gjesdal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 48-70.[⤒]

- Citing Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, and the anthropologist Ralph Linton, Spacks argues that the "cultural advance" of humanity "derives from the need to withstand boredom." Patricia Meyer Spacks, Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 2-3.[⤒]

- The psychological literature bears out this point, finding that boredom is consistently and strongly associated with aggression. See Julia Isacescu, Andriy Anatolievich Struk, and James Danckert, "Cognitive and affective predictors of boredom proneness," Cognition and Emotion 31, no. 8 (2017): 1741-1748.[⤒]

- Vincent Canby, "'Jeanne Dielman,' Belgian," New York Times, March 23, 1983. [⤒]

- I owe this observation about the coffee filter as hourglass to Ivone Margulies, who in turn credits the insight to the Belgian art critic Thierry de Duve. Margulies, Nothing Happens: Chantal Akerman's Hyperrealist Everyday (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 78.[⤒]

- I thank James Danckert for discussion on this point.[⤒]