Bored As Hell

In early 2020, before the pandemic, an artist visited the class I had been assigned as a teaching assistant. It was around the time I was writing my dissertation prospectus, and she asked me what I was working on. At the time still profoundly confused about precisely that question, I sought the comfort of a one-word answer that would do just fine to explain my topic and end the conversation about my dissertation. I said "boredom," and let the silence rest. "I don't know what boredom is," she confessed, soft-spoken and genuinely curious. I didn't know how to respond.

*

The task of defining boredom overwhelms Charlie Citrine in Saul Bellow's 1975 novel Humboldt's Gift. A successful writer, Charlie decides to write a treatise on boredom, which he calls "deep suffering." He admits that over the years "he kept being overcome by the material, like a miner by gas fumes," and stayed away "from problems of definition."1

It perhaps speaks to the challenge of pinning down what boredom is, that the word itself was, as Elizabeth S. Goodstein points out, "non-existent until the late eighteenth century," only coming "into being as Enlightenment was giving way to Industrial Revolution."2 Patricia Meyer Spacks similarly notes that the verb to bore first appeared in 1750 as a psychological condition, and the first occurrence of bore as a noun signifying a tiresome person is attributed to 1812.3 And in narrative fiction, the word boredom is believed to be first used in Charles Dickens's 1853 novel Bleak House, thanks to Lady Dedlock, who was "bored to death."4

Another nineteenth-century novel, Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (1871), offers a definition of boredom with the alluring economy of a one-liner: the "desire for desires."5 This charming formulation has been promiscuously quoted in boredom studies, hailed as the perfect description of boredom, and appeared in countless PowerPoint presentations. This was the boredom Anna Karenina's lover Vronsky felt in Italy, finally alone with Anna, whom he had thought was the key to his happiness. Yet while some English translators name Vronsky's condition as "boredom," others choose "ennui," further indicating definitional slipperiness while pointing to the fact that, though the word "boredom" is relatively new, it has close older cousins. Ennui, a term associated with "the pain of the soul in suffering from dullness," entered English usage from French in the late seventeenth century.6 Go back further still and we find that boredom has, "by whatever name," be it taedium vitae, horror loci, melancholia, been "a ubiquitous feature of the human condition."7 Medieval monks who had voluntarily withdrawn from society to lead a solitary life, devoted to sacred duties, were said to experience acedia, a Greek word signifying lack of interest. This word, Reinhard Kuhn explains, "became the recognized designation for a condition of the soul characterized by torpor, dryness, and indifference, culminating in a disgust concerning anything to do with the spiritual."8 Evagrius of Pontus (345-399 AD), one of the most influential theologians of the period, went into the North African deserts around the year 383 and adopted the life of a recluse counted acedia as one of the eight vices in Of the Eight Capital Sins, and called it noontide demon, which, he believed, "attacked the cenobites most frequently between the hours of ten and two," when "the hermit was weakest from fasting," and vulnerable to the "searing rays of the African sun."9

Such precedents notwithstanding, boredom's belated coinage in English is suggestive of what many scholars have argued: that the rise of boredom as a ubiquitous cultural condition is tied to the birth of industrial modernity.10 In The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin suggested that "[b]oredom began to be experienced in epidemic proportions during the 1840s."11 Modernity's reorganization and regimentation of labor and leisure transformed and complicated the experience of the passing of time, the connection of which to boredom is made explicit by the German word Langweile in a manner absent from its English equivalent. In his 1929-30 lectures at Freiburg, titled (and later published as) The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, Martin Heidegger asked, "how do we escape this boredom [Langweile] in which we find ourselves say that time . . . becomes long?"12 Heidegger exhaustively analyzed boredom by dividing it into three categories: becoming bored by (to use while waiting for the train in "the tasteless station of some lonely minor railway"), being bored with (to use when we are bored at a dinner party), and profound boredom (the final attunement, to use when boredom gets deep).13 Train stations and dinner parties as loci of boredom: tellingly modern, tellingly bourgeois.14

In his late essay "Free Time" (1969), Theodor W. Adorno linked the boredom of modernity to alienation at work, and observed it in the summer tan-line. In all seriousness, Adorno argued that "the act of dozing in the sun marks the culmination of a crucial element of free time under present conditions — boredom," and he believed that this desperate attempt to get something from the holidays or "other special treats in . . . free time" would, sadly, never "get beyond the threshold of eversame."15 More recently, by examining the "experiential transformations" of modernization, Elizabeth S. Goodstein has explained boredom as a "quotidian crisis of meaning" and, borrowing from the title of Robert Musil's unfinished three-volume novel The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), called boredom "an experience without qualities."16

"It's time to take boredom seriously," says Saikat Majumbar, the author of the 2013 book Prose of the World: Modernism and the Banality of Empire, which examines how boredom and banality shaped the aesthetics of modernist fiction in the aftermath of British colonialism. As previous examples suggest, the state of boredom, under different names, has in fact long been taken seriously in philosophy, theology, and literature. In the past few years, though, boredom has been gaining traction as a serious field of inquiry, with cross-disciplinary manifestations from psychology to architecture. More and more academic inquiries into boredom appear with each passing year.17

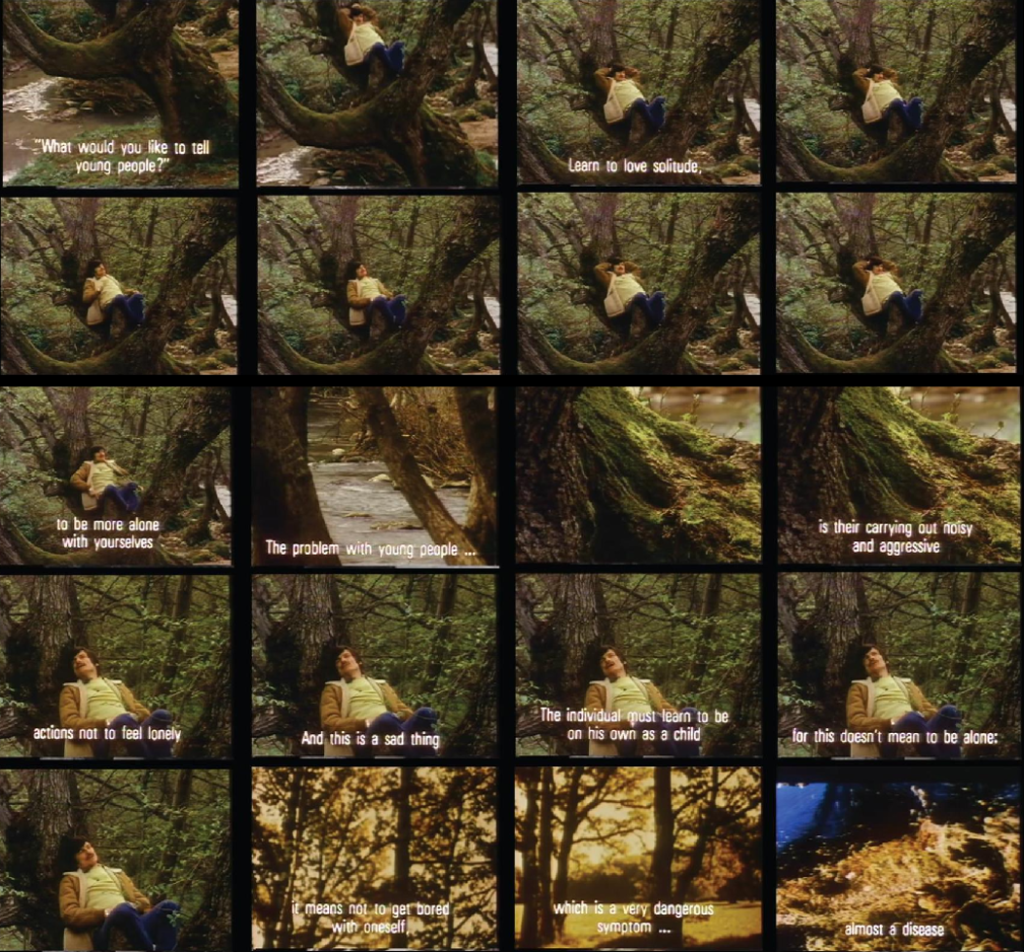

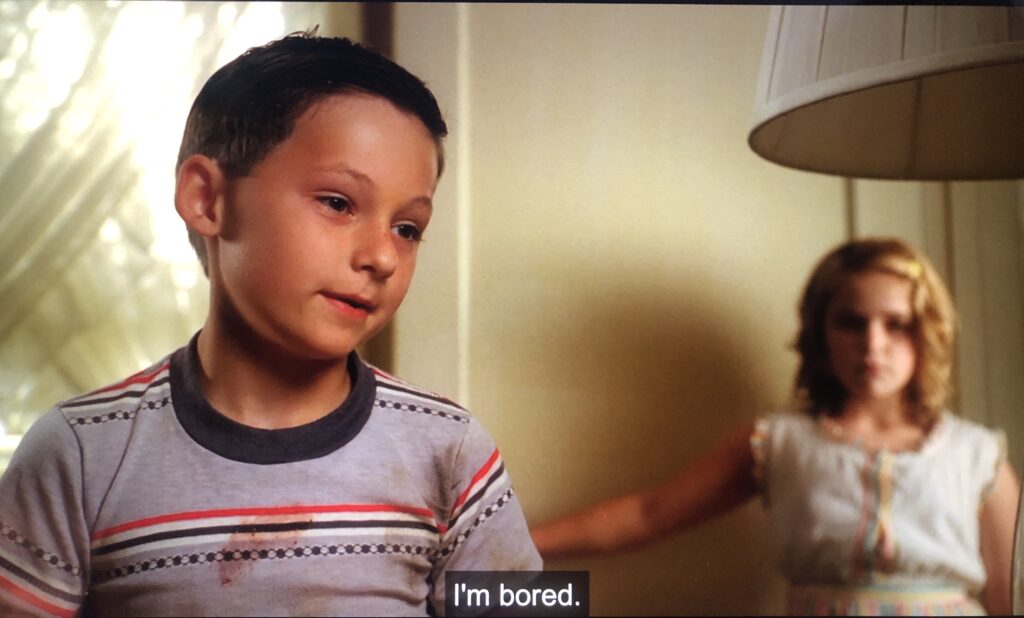

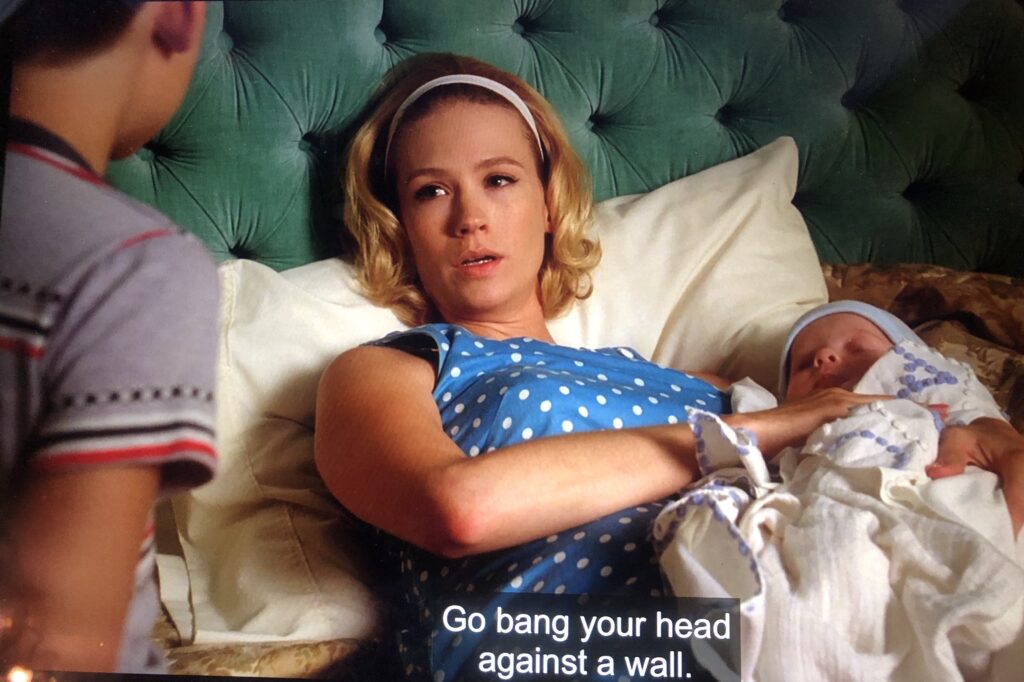

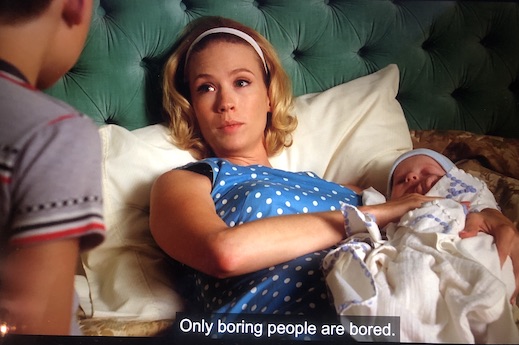

Studying boredom, however, need be neither tediously serious nor demand Heideggerian granularity. Tolstoy's is far from the only pithy one-line theory of boredom. Søren Kierkegaard's essay "Rotation of Crops" warned us that boredom is the root of evil.18 In his 2013 song "40 Acres," American rapper Pusha T said something similar: "the Devil's new playground is boredom."19 Other whimsical takes on the topic question the (im)possibility of boredom itself and rebuke others' failure to develop self-help strategies to sidestep boredom. Andrei Tarkovsky, for instance, while sitting in a tree, basking in idleness, advised young people "to learn to love solitude" (Fig 1). "Go bang your head against the wall," was what Mad Men's depressed housewife Betty Draper said to her son, who came to her and complained of being bored while she was unhappily resting in her bed holding her newborn son. "Only boring people are bored," she said and chastised her son away (Fig 2).

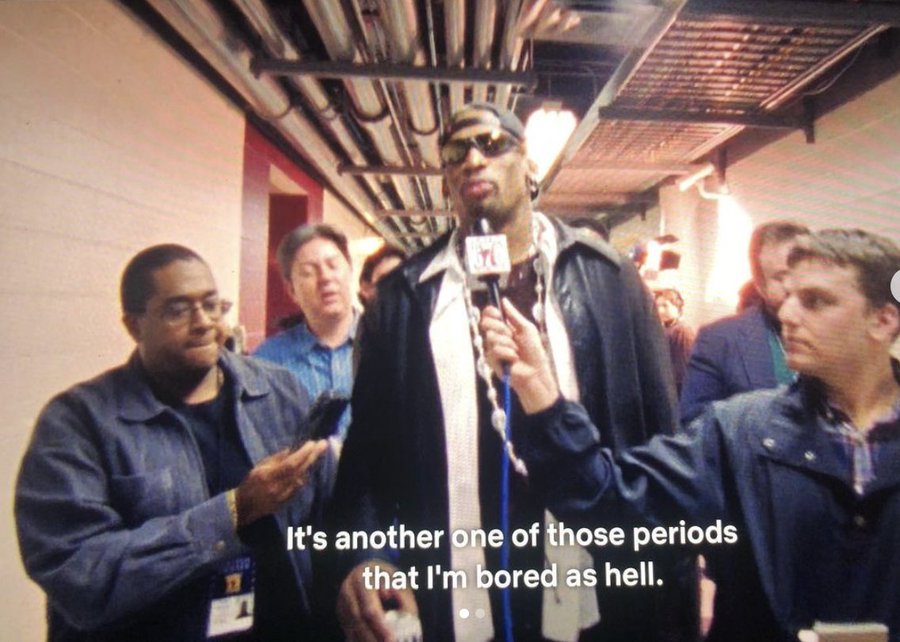

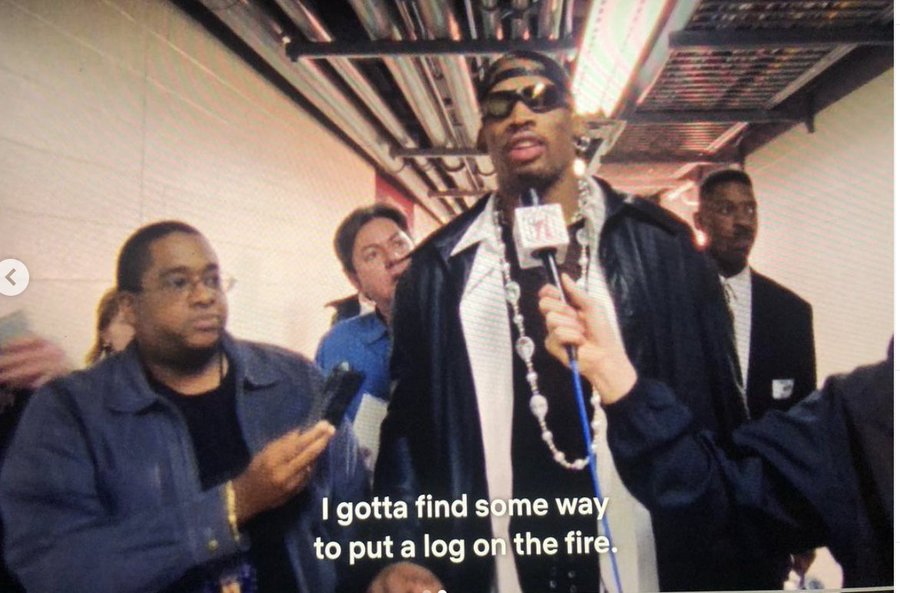

Sometimes we can only describe our boredom in terms of frustration and merely want to complain of being bored. Take the high school teacher George in Paula Fox's 1967 novel Poor George. Having spent a long time being unhappy, one day George explodes and screams at his wife Emma that he has been "[b]ored sick!" for a long time.20 Or consider Gertrude Stein who, upon leaving medical school, complained to Marion Walker: "you don't know what it is to be bored."21 Or recall former Chicago Bulls rebounder Dennis Rodman who, one day in the '90s, not feeling motivated to play, told the cameras that he was "in one of those periods that [he was] bored as hell" and needed to "find some way to put a log on the fire" (Fig. 3). And sometimes, resigned to our boredom, we can only say, "I'm not in the mood."

During the pandemic lockdowns, more people tried to understand boredom. For most, time became long every day; for some it came with the additional chaos of bored children. Many people sought comfort in various self-care routines to stave off boredom as well as pandemic anxiety. News outlets sought to explain boredom to us and show us how we could make "good use" of our time in involuntary solitude, publishing pieces with self-help strategies: What Does Boredom Do to Us and For us?; Five ways boredom could be changing your behaviour; Depressed or bored?; Pandemic might be an opportunity.

In this cluster, you will find many boredoms. Six essays by six scholars from different disciplines and research areas offer contrasting meditations and reflections on different forms of boredom and boringness.

Beth Blum slowly and carefully assembles musings on boring hospital art, inspiration, un-boring the boring, wounds hidden in the clichés of trauma narratives, and death. Sarah Chant reads boring and banal moments in Dostoevsky and Elif Batuman to construct a relationship between boredom and humor, and shows us that tedium need not necessarily be tedious. James Danckert, the only cognitive neuroscientist in our mix, considers the tedium of immortality — if we have all the time in the world, what is at stake? Joel Faflak ruminates on the state of higher education, the corporatization of learning, wasting time, and the possibility of boredom as a productive response to the quantification of productivity, progress, and happiness. Yonina Hoffman bears with bored workers in contemporary fiction, diving from David Foster Wallace's The Pale King to Ling Ma's Severance, into the trauma and self-loathing of office workers — though not without some gleams of hope. Finally, Charlie Tyson works with bored housewives, and, from Anton Chekhov's Sonya to Henrik Ibsen's Hedda Gabler, to Chantel Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, alongside Picasso's still lifes, slowly walks us through the quiet violence of the domestic.

When I first began thinking about boredom, I wondered if we should just shelve it as maddening and leave it at that, or could there be more to say about boredom beyond a mere utterance of frustration? Throughout these essays, we find that the answer is very much the latter. If nothing else, though, I hope that reading these essays will be a way to spend a couple of idle hours — ideally, when you are bored . . .

Busra Copuroglu (@buscopur) is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada. She is writing a dissertation about literary depictions of boredom and complaint.

References

- Saul Bellow, Humboldt's Gift, (New York: Penguin Books, 1986), 108-9, 199[⤒]

- Elizabeth S. Goodstein, Experience Without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 3.[⤒]

- Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 13. For more on the uses of the word boredom, see Patricia Spacks, Boredom: Literary State of Mind.[⤒]

- Then, in George Eliot's Daniel Deronda in 1876. I owe this observation to Elizabeth S. Goodstein's The Experience Without Qualities, 107. [⤒]

- Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, translated by Constance Garnett (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 670.[⤒]

- Dmitri Nikulin, Critique of Bored Reason: On the Confinement of Modern Condition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022), 2; Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 14.[⤒]

- Goodstein, Experience Without Qualities, 33.[⤒]

- Reinhard Kuhn, The Demon of Noontide: Ennui in Western Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 40. [⤒]

- Kuhn, The Demon of Noontide, 43.For more on the history of boredom see: Peter Toohey, Boredom: A Lively History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011).[⤒]

- See, for example, Elizabeth S. Goodstein, Experience Without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005); Essays on Boredom and Modernity, edited by Barbara Dalle Pezze and Carlo Salzani (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2009); Peter Toohey, Boredom: A Lively History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011); Boredom Studies Reader, edited by Michael E. Gardiner and Julan Jason Haladyn (London and New York: Routledge, 2017); Dmitri Nikulin, Critique of Bored Reason: On the Confinement of Modern Condition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022). [⤒]

- Walter Benjamin, "Convolute D: 'Boredom [D3a, 4],'" The Arcades Project, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 108.[⤒]

- Martin Heidegger, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, and Solitude, translated by William McNeill and Nicholas Walker (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), 78, emphasis in original.[⤒]

- The Fundamental Concepts, 93, xix. The translators note that one "major difficulty is that the English word boredom, which translates the German Langweile, is unable to convey the temporal sense which Heidegger makes central to his phenomenological analyses. The German Langweile literally means long while, and Heidegger, taking this up, will argue that the various forms of boredom are ultimately nothing other than various ways in which time temporalizes," xx-xxi.[⤒]

- For Heidegger, it is important to distinguish becoming bored by from being bored with, as the latter, he argues, is "tied in with the inner essence of boredom in general," which he later analyzes in his discussion of profound boredom. To explain the nuance between these two forms of boredom, he finds it necessary to utilize "distinctly everyday" examples "accessible to everybody," 109.[⤒]

- Theodor W. Adorno, The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture, edited by J.M. Bernstein (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 191.[⤒]

- Goodstein, Experience Without Qualities, 1-2.[⤒]

- To name a few: Peter Toohey, Boredom: A Lively History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011); Boredom Studies Reader, edited by Michael E. Gardiner and Julan Jason Haladyn (New York and London: Routledge, 2017); Andreas Elpidorou, Propelled: How Boredom, Frustration, and Anticipation Lead Us to the Good Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020); James Danckert and John D. Eastwood, Out of my Skull: The Psychology of Boredom (Cambridge, Massachusettes, Harvard University Press, 2020). The Moral Psychology of Boredom, edited by Andreas Elpidorou (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021); Dmitri Nikulin, Critique of Bored Reason: On the Confinement of Modern Condition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022). For a more comprehensive list of publications on boredom, see Boredom Society Publications. [⤒]

- Søren Kierkegaard, "Rotation of Crops," in Either/Or Part I, ed. & trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 285.[⤒]

- Pusha T ft. The-Dream, "40 Acres," track 6 on My Name is My Name, GOOD Music / Def Jam, 2013.[⤒]

- Poor George, (New York and London: W.W. Norton Company, 2001 [1967]), 78.[⤒]

- The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (London: Penguin Books, 2001), 91.[⤒]