Gestures of Refusal

I think of refusal as one of the most highly effective modes of resistance. I refuse to be faithful.

— Don Mee Choi

In the world of translation, no term is more vexed, more overused, more fraught with contradiction than fidelity. At its most basic, the OED tells us, fidelity denotes "the quality of being loyal to somebody or something" — a definition that makes clear the moralizing dimensions of the term. An unfaithful person is a betrayer, a usurper, someone not to be trusted. An unfaithful translator, similarly, takes advantage of their unique position to perform multiple betrayals: of their audience, the author, the country, of the language itself. Given the term's association with marriage and the qualities traditionally expected from wives — purity, loyalty, adherence to a set of male-prescribed rules — it's perhaps unsurprising that female translators have, historically, been the ones most vulnerable to charges of unfaithful translation. The first generation of feminist translators / translation studies scholars tended to take the long history of "les belles infidèles," and French rhetorician Ménage's claim that, "like women, translations must either be beautiful or faithful," as a point of departure for their critique.1 Their scholarship sought out and embraced resistant translations that purposefully departed from — or "womanhandled," to use one popular formulation — the source text.2

In the years since the emergence of feminist translation studies in the late 1980s, translation criticism has flourished under the influence of postcolonial scholarship and queer theory. The current climate is one in which the racialized, imperial, and gendered contours of translation work are attended to with more care than ever before. The call to move away from fidelity-guided assessments of translation has, at the same time, grown stronger and stronger: translation studies scholars working across postcolonial languages or cultures have been quick to note fidelity's association with forms of mastery and called for an embrace of "errant, disobedient translations" as a way to reject such colonial logics, or to reckon with the various layers of privilege that translators and their texts inhabit.3

And yet, fidelity is a slippery thing. There is a tendency to default to the language of fidelity, even when one claims to reject it outright. This is the central claim of Lawrence Venuti's recent, grumpy-yet-fun treatise, Contra-Instrumentalism: A Translation Polemic (2019), which bemoans the enduring influence of fidelity discourse in most venues in which translation is discussed. According to Venuti, merely to mention a translation's "source text" is to conjure fidelity criticism because it frames translation work in utilitarian terms, where the end goal is to preserve or recreate something of an original. He advocates instead for a hermeneutic model of translation with an emphasis on not only the creative and scholarly dimensions of the translator's work, but the centrality of translation to all aspects of social, cultural, and political life. All translation, Venuti argues, "is an interpretive act that necessarily entails ethical responsibilities and political commitments," and this is the case irrespective of the genre of translation in question, its shape, style, or context.4

Understanding translation in this way — as a set of artistic and cultural practices that should be evaluated according to their own ethical responsibilities and political commitments, outside the frame of fidelity — requires us to rethink the idea of refusal such that it no longer means declining to conform to the style of an original, the gendered conventions of a language, or cultural commonplaces. Refusal, rather, hinges on the idea of translation as central to everyday life, omnipresent and yet unacknowledged, unseen. Though we live in a moment where translation technologies are ubiquitous and platforms like Netflix offer content in any language at the touch of a button, the ethical and political dimensions of this act — of this seemingly smooth and instantaneous movement across language and culture — are seldom questioned. Venuti has elsewhere described the translator's "invisibility" as a key part of how this work gets erased: by obscuring the agent (and therefore, the work) of translation, its political implications and in-built biases are sloughed away.5 What, then, would it take to make the invisible visible? Put differently, given translation's taken-for-granted status (especially in the Anglophone, monolingual west), what would it mean if the people who performed the bulk of the labor of translation into English just stopped? What if they refused to make themselves (and their histories) legible? What would that look like? Refusal, then, becomes central to the act of translation precisely because it resists invisibilizing labor and smoothing out complicated, layered cultural contexts.

It's this version of refusal that activist-translator-poet Don Mee Choi places front and center in her work. Choi, who was born in South Korea and lived there through the worst years of the US-backed Park Chung-hee dictatorship, fled to Hong Kong with her family in 1972, where she remained before making her way to the US for her studies some years later. Now based in Germany, Choi has spent her career obsessed (her word) with writing about a singular topic: the "overlapping histories of Korea and the US."6 She has approached this project in a variety of ways: through activism (her work with the International Women's Network Against Militarism), through her translation work (South Korean feminist poet Kim Hyesoon and experimental revolutionary Yi Sang), and by unravelling her own familial history in relation to the larger geopolitical histories she obsessively studies. Choi is a historian as much as she is a poet and translator, and her writing style insists on the interconnection between poetic, historical, and translational modes of expression. She understands that history, like translation, suffers from a presumption of objectivity: the public trusts that translations and histories are objective, but the translator's own politics inevitably shape what gets written down. Whether or not a translation or version of history finds currency depends entirely on the geopolitical climate and conditions of power it emerges from or speaks to. Choi excavates and works through these tensions in her poetry.

In 2016's Hardly War, Choi probes this line between the personal and collective using photography as a medium. Choi's father was a war photographer, both in Korea and the larger Asia Pacific region from the 1950s through the 70s. That the profits from this photographic work are what enabled Choi's family to escape the Park dictatorship is a source of unease throughout the collection:what does it mean to witness and record such atrocity? To materially benefit, even unwittingly, from this witnessing? What uncomfortable kinship structures have emerged out of U.S, military involvement in Asia, from Korea to Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines? Choi negotiates these questions in part by recognizing that photography, much like translations and works of history writing, can easily be co-opted by ideology. Whatever one intends to accomplish through these modes of artistic expression — in her father's case, to bear witness to and document the atrocities being committed — this intention can be easily appropriated, skewed to fit another agenda entirely. Such is the example Choi sketches in one of the collection's poems, "Operation Punctum." In this work, Choi culls dialogue and narrates footage from The Deer Hunter (1978), the American Vietnam War film. In the notes to Hardly War, Choi recalls that she first watched the film with her father in a "jam-packed theater in Hong Kong," and that she had only learned very recently that the news footage in the film was her father's. In one quick associative move, Choi demonstrates how easily photography — even of the journalistic variety, which ostensibly seeks to document or represent things objectively — can be put to use in a harmful nationalist narrative. She also shows how easily these manufactured narratives circulate, such that even "jam-packed theaters" in Hong Kong — historically a refuge for people fleeing America's pacific wars in other locales — can passively consume this narrative.

If the Vietnam War is "the most-photographed war in television history" and the most well-known of all US military efforts in Asia, the Korean War is often depicted as a comparatively brief struggle, lasting just from 1950 to 1953. When spoken of, it is typically referred to as "the forgotten war," a designation emblematic of a very particular brand of US martial cruelty. How else could one refer to such an event — a conflict that razed 85% of Korea's built environment to the ground, killed 3-4 million people, arbitrarily divided the Korean peninsula and which, despite an armistice agreement signed in 1953, is technically still ongoing — as "forgotten"?

Writing about the legacies of America's wars in the pacific theater, Sunny Xiang argues that, by reading history through the lens of war — and understanding war as a struggle with a discrete start and end — liberal humanists inevitably "end up fetishizing crises, ruptures, and breaks."7 The US public's inability to identify any such rupture or end point in reference to the Korean War, coupled with US participation in a seemingly endless rotation of conflicts abroad and a media climate that demands ever more spectacular displays of violence for crisis to be recognized as such, has meant that some degree of forgetting seems all but inevitable. But Choi pushes back against this impulse. "I refuse to perpetuate the official narratives of the Korean War, which thingifies," she says, referencing Aimé Césaire's term for the processes of dehumanization required for colonialism and domination (in various forms) to take root.8 For the US to figure itself as the benevolent protector of vague liberal values like "democracy" and "freedom" abroad, their agential role in this protracted struggle must be minimized through narrative strategies (i.e, ascribing a start and end date to an ongoing conflict) that cast these events as stabilized relics of the past.

In Hardly War, Choi stages this refusal in a style we might describe as both confrontational and unhinged.Confrontational because in refusing to translate the Korean text for an English-speaking audience, Choi asks her readers to acknowledge the authoritative presence and hegemony of English, the way that English and the US-based audience is always considered the default. Unhinged because the poetry is a mad mix of photography, Korean and English script, transcripts from political conferences and history books, film dialogue, musical scores, and illustrations of various provenance. Implicit in the connotation of unhinged is a decoupling action: for something to become unhinged, there is a decisive move away from, or break with, a long-established point of connection. In Hardly War, unhinging happens at the level of form and history. Formally, Hardly War is an extremely difficult text, even for the reader conversant in all of these languages or modes of expression. But it needs to be difficult because history — if one chooses the non-thingified version — is difficult, contradictory, and often nonsensical.

This was something that one of Choi's heroes, Yi Sang, understood very well. Writing during the Japanese occupation when the Korean script Hangŭl was banned, Yi often wrote in code: elaborate scripts of numbers, punning, wordplay and rhyming patterns. In an interview with Christian Hawkey about her translational politic and the genesis of Hardly War, Choi talks about the influence of Yi Sang on her work, the way that madness can be a sustaining aesthetic principle in its own right:

I came to know Yi Sang's work because he was my father's favorite writer. Yi Sang kept him sane during his youth, which was during the Japanese occupation of Korea, a bleak period, needless to say. And as my father was deciphering some of the Chinese characters in his poems for me, he pointed out, fondly, that Yi Sang was a "mad man," "an iconoclast." (Last year, when asked what he thought of my book Hardly War, he replied, "She's not an average writer." I was hoping he would say, "She's totally mad.")9

For Choi, then, "madness" is a high form of praise, and when I suggest that Hardly War is unhinged I mean it as such. Through its use of pastiche, Hardly War shows how audiovisual media often works, like translations or works of history, to impose a narrative logic onto events that are themselves illogical, using aesthetics to distract from the horrors of war and colonialism. There is a mad quality to this, and that madness is central — needs to be central — to the tone of the work.

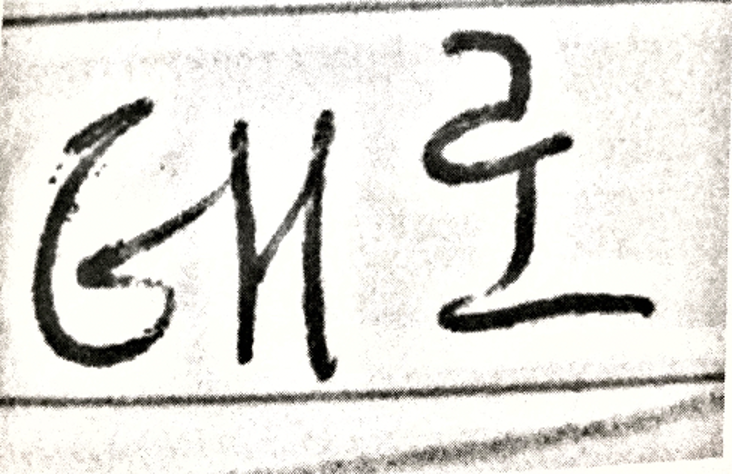

The piece that perhaps best exemplifies this tendency in Hardly War is the poem in which Choi names her refusal explicitly. The poem, entitled "With her Brother on Her Back / I Refuse to Translate," appears as follows on the page:

This poem reads in a couple of different registers. For non-readers of Korean, the possibility of accessing the poem's critique is, significantly, foreclosed. By limiting the English reader's access to the refrain I refuse to translate, Choi is deploying the confrontational mode, calling attention to the ways the English audience relies on and expects immediate, faithful, and informative service from their translator. Unlike other moments in the collection where Choi provides some historical context or translates Korean text for her English readership in the accompanying glossary, the only contextual note provided for this poem refers to the provenance of the photograph at the top of the page, which is described as follows: "From the US National Archives: 'With her brother on her back, a war weary Korean girl tiredly trudges by a stalled M-26 tank at Haengju, Korea, 06/09/1951.'"10

What's at stake in this refusal to translate is therefore primarily accessible to the Korean readers in Choi's audience, a reversal of the typical dynamic in which English readers have fullest access. What is written in Korean below the photograph is a refrain from a popular song; literally translated, it reads: the rose of Sharon has bloomed. Fans of the recent South Korean Netflix hit Squid Game would recognize this song as the one that accompanied the murder doll game in the opening episode, where it was lazily translated as "red light / green light." The song takes on a different valence when one considers that 무궁화, or the rose of Sharon, is the national flower of Korea and often taken as a metonym for the nation itself. Within the context of the collection, which explores (amongst other things) the military atrocities South Korea committed against the Vietnamese during the Vietnam War, this childlike tune masks a darker meaning. The blooming of South Korean nationalism out of conditions of colonialism and war was predicated, Choi suggests, to some degree on taking on characteristics of the neocolonial order and committing violence in its name.

The photograph at the top of the page, paired with the US National Archive description included in the accompanying notes, crystallizes this eerie disjunction between what is said and what is really being depicted. In this case, the somber child is depicted as resilient; the tank as a symbol of the US' benevolent protection, a source of refuge for the "war weary." By refusing to translate both the photo and the Korean parts of the poem, Choi calls attention to the uneven terrain of history itself: the gulf between who gets to narrate histories, the subjects described (or not described), the subjects given or denied voice. Choi suggests that it's those subjects who have historically been denied representation who translators are in a particularly unique position to help.

The 2020 National Book Award-winning collection DMZ Colony offers a keen vision of what this kind of translation work — work that seeks to give expression to the historically marginalized — might look like.Heavily experimental in the vein of Hardly War but more accessible, DMZ Colony takes as its subject the ways language unites and bifurcates, its tangible and enduring geopolitical consequences, the ways it produces violence on the body and on the planet. If Hardly War is about refusing to condone or translate the dehumanizing stories told about the Korean War, then DMZ Colony seeks — through a very different kind of translational refusal — to give presence to those whose lives are unfairly jettisoned from history. Much of the work centers around Choi's 2016 return to South Korea and meetings with local activists, including Ahn-Kim Jeong-Ae, a feminist activist and scholar whom she knows through her involvement with the International Women's Network Against Militarism. At the time of their meeting, Ahn-Kim had been involved with investigations into a number of historical abuses in Korea, first those committed during the Park Chung-hee dictatorship, and most recently, into massacres of civilians that took place just before and during the Korean war. The two meet over lunch in a crowded Seoul restaurant, and Choi describes how Ahn-Kim diagrammed the massacres on scrap paper, "mapping out for me unspeakable orbits of torture and atrocities," which she includes in the collection as well.11 The unasked question here, of course, is: how does one even begin to approach the project of representing such horror, knowing that it is impossible? What shape(s) would it take, if it could be rendered in full?

Choi answers this question in part by offering up her own version of an archival assemblage. Among the materials gathered in the collection are two pages from the 1951 record of the Counterintelligence Corps of South Korea on the Sancheong-Hamyang massacre, which she translates and interprets for her English-speaking audience. She notes how this atrocity was until recently lumped together with the more well-known Geochang massacre — a conflation, according to Ahn-Kim, that means the state "continues to suppress knowledge regarding the mass executions of civilians that took place before and during the war."12 This probe into the Samcheong-Hamyang massacre culminates with a series titled "the Orphans." In this section, Choi reproduces eight accounts from war orphans who survived the Sancheong-Hamyang massacre, ranging in age from seven to sixteen. The poems in this section are arranged in such a way that suggests translational equivalence: on the left-hand side of the page are the orphans' horrific accounts of what they experienced, handwritten in childish Hangul; on the right, Choi's blunt, disarming rendering of their words in English.

When I came to the notes section of the collection and learned that these were not archival findings but rather composite "imagined accounts" based on conversations with Ahn-Kim and survivor testimony, I was shocked to find that my initial reaction was a kind of anger. How dare we be confronted with such horror, only to find that it has been fabricated, manipulated by the poet-translator? But, I came to realize, this is precisely Choi's point about translations and poetic language. Because these modes are always seeking to give expression to something that resists comprehensive depiction, and because they inhabit this realm of inexpressibility and intangibility, they are particularly well-suited to warding off bad interpretations of history (of, for example, The Deer Hunter variety). In her acknowledgements, for instance, Choi notes that the friends and family of Ahn Hak-sŏp — a political prisoner whose life she brings forth in this collection — wished that she had written an article for a famous newspaper about his story, but that she had refused. She opted for this more experimental mode because, she writes, "poetry is more effective as a language of resistance. Poetry can defy erasure."13

The events described in DMZ Colony are devastating, horrific, and yet somehow beautiful. My choice to (largely) not quote from the text is deliberate, both because I will not be able to do Choi's words justice, and because I think that DMZ Colony is essential reading for anyone invested in questions of justice, reparation, and global humanity. Call it my own kind of refusal. And in Choi's own words, which will make sense if you read the collection:

Onward.

Claire Gullander-Drolet is a writer and teacher from Montreal currently based in Hong Kong, where she is a postdoctoral fellow in the Society of Fellows in the Humanities at the University of Hong Kong.

References

- Sherry Simon, Gender in Translation: Cultural Identity and the Politics of Transmission. Routledge (1996): 10[⤒]

- Barbara Godard, "Theorizing Feminist Discourse/Translation," in Translation, History and Culture, edited by Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere (London: Pinter), 50.[⤒]

- See Kaza, Kitchen Table Translation (Blue Sketch Press, 2017, X) as well as Deborah Smith, What We Talk About When We Talk About Translation (Los Angeles Review of Books, 2018). https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/what-we-talk-about-when-we-talk-about-translation/.[⤒]

- Lawrence Venuti, Contra-Instrumentalism: A Translation Polemic (Nebraska Press, 2019), 6.[⤒]

- See: The Translator's Invisibility: A History of Translation (Routledge: 1995).[⤒]

- Don Mee Choi, "An Interview with Paul Cunningham," ActionBooks. https://actionbooks.org/2021/04/don-mee-choi-an-interview-with-paul-cunningham/.[⤒]

- Sunny Xiang, Tonal Intelligence: The Aesthetics of Asian Inscrutability During the Long Cold War (Columbia University Press: 2020), 5.[⤒]

- Don Mee Choi and Christian Hawkey, BOMB. The Capilano Review, January 16, 2018. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/don-mee-choi-and-christian-hawkey/. [⤒]

- Don Mee Choi and Christian Hawkey, BOMB. The Capilano Review, January 16, 2018. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/don-mee-choi-and-christian-hawkey/.[⤒]

- Don Mee Choi, Hardly War (Wave Books: 2016), 92[⤒]

- Don Mee Choi, DMZ Colony (Wave Books: 2020), 39.[⤒]

- Don Mee Choi, DMZ Colony, 88.[⤒]

- Don Mee Choi, DMZ Colony, 131[⤒]