Gestures of Refusal

Lake

In dreams, I circle a page. It is lapis, lapping, with arms of water. I wake up on a November morning and write:

I meet at the page: water. I meet at the water: a former I. I with sleeves worn out, with dewstains blue. I of a hardness, and hard storms. A look of being left too soon. Or broken out of — the air still quivering above.1

Each time I speak, I speak with this thing marking me as a speaker. This I. This I speaking here, writing here, working toward something, something. This is the I that I have harnessed and hardened on the page. There were many before this; there are many beyond here. The former I that I meet at the water is blue. She is pooling into a history I can't grasp. Somewhere along the way, I broke out of her. At each page, its waves, she's there.

Somewhere along the way: a Maoist movement, a civil war, a migration, Grandparents waiting, a wide gash of time.

In his book Motherless Tongues, Vicente Rafael explores the tenuous relationship between language and the postcolonial migratory subject. He writes," I express myself, as Octavio Paz says, only by breaking with myself. My identity comes not from being the same but from differing, drifting, and detouring, always intermediate and interconnected: always addressing, addressed by, and becoming, in turn, a you."2

Each I of mine is also a you; each you is an I. The hard line between the two dissolves at each utterance. I am speaking to you — at the mouth of the lake — I am speaking to you, you are speaking to me, I am you, you are me — an I lingering, lingering.

Creek

Water interrupts lines. Breaks below their shape and opens the ground, the page, the hard hard thing. I let water flow between the images, the words, the you and the I. I let water widen the gaps.

River (i)

When the Treaty of Sugauli was ratified in 1816 between Gajrarj Mishra — the royal priest to the Shah Dynasty — and the British East India Company, Nepal ceded significant portions of land. Significant portions of land violently conquered by the Shah Dynasty were then violently taken over by the British East India Company. I read:

3. The king of Nepal will cede to the East India company in perpetuity all the under mentioned territories:

- The whole of low lands between the Rivers Kali and Rapti.

- The whole of low lands between Rapti and Gandaki, except Butwal.

- The whole of low lands between Rapti and Gandaki a [sic] Koshi in which the authority of the East India Company has been established.

- The whole of low lands between the rivers me chi [sic] and Test [sic].

- The whole of territories within the hills eastward of the Mechi River. The aforesaid territory shall be evacuated by the Gorkha troops within forty days from this date.3

At first glance, the treaty stands careless to the movement of water and of people. Small, condensed, the language stiff and wooden; there is little room for that which has preceded the treaty, that which has moved and lived before it, that which has moved to live. But I want something that seeps.

~

I want something that seeps: something about the slippage in the spelling, the falling of seemingly unfaltering language. The original treaty has been missing since 2019.4 I read transcriptions and traversals instead. Is there seepage in this — in the lapses and apertures? The water crashing against the word — is this an erosion?

~

Susta is a disputed territory along the border of Nepal and India. When the Treaty of Sugauli was signed, Susta was on the right side of the Gandaki River; the river's shifting course means that it is now on the left.5 The irony of wanting to contain something that disrupts the very idea of containment is laid bare here.

Pool

We shall meet again, in Petersburg - Osip Mandelstam

From an untitled poem, that opening line announces heartbreak as its craft: a promise like that already holds its own breaking.6

— Agha Shahid Ali

Much of Ali's work holds its own breaking. A yearning, a seeking, a routing back to his home Kashmir through and on the page. He later echoes Mandelstam's line in his own poem "A Pastoral": "We shall meet again, in Srinagar."7

We shall meet again. I am trying to route back, by learning. By which I mean, I am trying to pool into a history I can't grasp. I am trying to meet you, my former I. I am trying to sink into the archive, the stories, the scraps; stepping into water and getting lost, becoming porous, stepping into an overwhelm. Its shape a wide open whirl; everything swims here — here, here: the page.

For Ali, you is the container of yearning. The thing toward which he reaches. Writing about Majnoon and Laila, he explains:

The Arabic love story of Qais and Laila is used — in Urdu and Persian literature — to cite the exalting power of love. Qais is called Majnoon (literally "possessed" or "mad") because he sacrificed everything for love. The legend has acquired a political dimension, in that Majnoon can represent the rebel, the revolutionary who is a model of commitment. Laila thus becomes the revolutionary ideal, the goal the Lover/Revolutionary aspires to reach.8

When Majnoon cries, "Beloved/ you are not here," he is addressing a lost love, a revolution.9 But what happens when he gets to the other side? What happens when Laila can't hold his ideal, either as lover or revolutionary? Has his commitment to his search, his seeking, eclipsed the subject of his search — has his love eclipsed his beloved? His is, as Ali would say, a "longing so flawed."10

Mine is a longing so flawed; I — this I, this seeking, routing, searching I — holds its own breaking. Its constant reach toward fullness, a constant break. I flip through my own poems and read:

A season of grief has turned to years: I watch my grandmother

circle her garden: fallen rosebush & fleeting light,

this trepid English summer. We flit toward the window

when the sun rises noon, like two bugs to a bulb. From her,

I inherited a practice of halving, a muslined

body. I didn't inherit the rest. When we sit

together to write — government forms, their staunch boxes —

we lose. After me, she replaces a country. Still, we

press petals into palms. We press hands. We know there are words

we don't say. Evenings, I read: foot soldiers, blows & cuffs,

underground. Reticence is a diet, so we cook.

Lentils, okras, pots of rice. Evenings, I admit I don't

know much. I count the fennel blooming on the sill. There must

be, I say, an abundant field somewhere. Green, flagrant, calm

as the head of a clove. It won't drone with the deaths it's seen —

it won't have seen any. We must visit, she says, one day.

We shall meet again, we shall meet again. We must visit one day, we must visit one day. We may never meet again, we may never visit. To promise that which cannot quite be promised, if only to satiate a longing. This is heartbreak as craft. An I's own longing — an I here having bloomed into a we.

Sea

I read that etymologically revolution can be traced back to the old French revolucion, the revolving and turning of celestial bodies.11 The slow turn, slow yearn of things. I think of one pulling the other — the moon pulling the sea; the word pulling the letter, the people pulling the people: revolution.

~

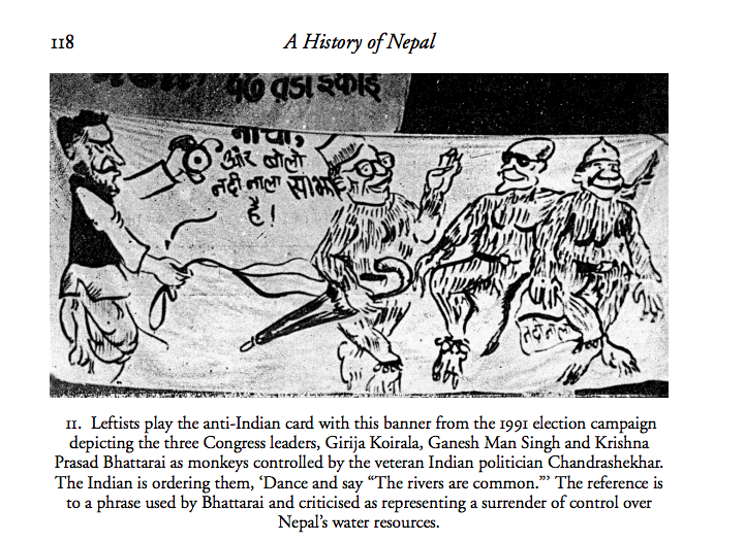

In 1990, Nepal's Jana Andolan (literally "the People's Movement") abolished the absolute monarchy rule, known as the Panchayat system, which had outlawed political parties for three decades. The Congress Party, in collaboration with Communist groups, entered into negotiations with the then-king Birendra.12 The strained political relationship between the Congress Party and the different Communist factions played out during, and long after, the negotiations. At various points, they disputed over the complete abolition of the monarchy, the secularity of the state, the recognition of minority and suppressed languages and people, and over water resources.13 But on April 8, 1990, an announcement aired across televisions, explaining that "partyless" would no longer appear in the constitution. People took to the streets to celebrate.14

The photo above has been considered "iconic" of the Jana Andolan. Durga Thapa, who was 22 at the time, sprang up into the air to declare "Long Live Democracy" the morning after Birendra's announcement. The photo was captured by Min Bajracharya, who was 18 at the time. This was an anomaly in the mainstream political photography landscape in Kathmandu. Devoid of major party figures, the photograph became a symbol of the people's movement: a relief, release — however short-lived — from an oppressive system, and the list of dead that trailed past the moment of Birendra's announcement.15 I read:

Thirty years later, [Bajracharya] still has vivid memories of what he saw and photographed on the night of 8 April 1990 when police, who were unaware of King Birendra's proclamation on national television to restore democracy, fired on jubilant protesters in Kathmandu, killing many.

He can still hear the crack of bullets ricocheting off the houses. "Many people lost their lives needlessly. I am still haunted by what I witnessed that night."16

~

In the midst of injustice, Majnoon calls to Laila, "it is a strange spring / rivers lined with skeletons."17 Water seeping into bodies, sweeping them away. What remains is a hollow map to what once was. When Grandfather passed, we kept his ashes for a year before releasing them into a large pool of blue. We watched his remains line each wave, until they sunk into themselves.

Elsewhere, Ali writes, "in each new body I would drown Kashmir."18 In each encounter of love, sex, desire, he seeks a watery concurrence — pulling home into his lover's body, meeting his lover through the body of home.

~

The strained political relationship between the Congress Party and the different Communist factions played out during, and long after, the negotiations.19

Boats at the dock

Like Ali, I am wrestling with my yous.

Although he is long gone, I think often of L., a former lover. Something about our writing out love as we experienced it. A strange act of ego. But also, an act of building each other out. He became my you; I his. We placed each other directly in front of each other, words treading the lines we'd drawn. On the back of an envelope, I wrote down:

When, L., we stood under the rushing stream in your bathroom, I felt time beat against our skin, like boats at the dock. I'd first felt it years before, when I rode in the black night to Tribhuvan International with my family and took flight. I remember: the date (May 5, 2005), the name of our new country (Canada), the procession of loved ones leading us to the car, the car rocking buoyant against prematurity. As with most of the things I loved, I left too soon.

~

Like Ali, I am trying to route back through and on the page. I read erratically, water widening the gaps between words, paragraphs:

Nepal's 10-year long Maoists rebellion, [

] nearly 16,000 [ ] killed during [

] lasted from 1996 until 2006

[

] Nepal's civil war pitted the Maoist-led People's Liberation Army (PLA) against state forces [

] About a third of the PLA fighters were women [

] the army, which is thought to have been behind most of the 1,400 suspected cases of enforced disappearances that took place during the conflict [

], a breakaway Maoist group called the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), enjoys the support of many former Maoist fighters who believe that the mother party, the CPN (Maoist-Centre), made too many compromises after entering government in 2006. [

] In 2008, the Maoists won the country's first Constituent Assembly elections, [ ] In its first sitting, it scrapped the 240-year-old Shah monarchy. [

] But did the war bring about the change Sita fought for? [ ] She feels their leaders "kneeled and surrendered" [

] "People thought the war will bring total change, especially for the poor, who would be guaranteed food, shelter, health and employment," says Sita, who is now a member of the central committee of another breakaway Maoist party headed by Mohan Baidya, who is known by his nom de guerre, Kiran. [

] [ ] "The state, mainly the armed forces, used to go into villages and torture, kill, threaten to kill the family members of Maoist members, PLA fighters, and their supporters just on the basis of information from their spies," [ ] Shree feels the victims are still ignored, and that the true extent of the war crimes committed remains hidden. "The rape victims have not made their cases public. Almost all such rape cases were committed by the armed forces," she says. [

] Did the war change the country for the better? Shree doesn't think so. "First, Maoists tried to win people's hearts. If they failed, they used force, such as kidnapping or killing," she says. [

] Nearly 85 percent of those who "disappeared" in Bardiya were Tharus. [

] 90 percent of "disappearances" were carried out by the police and army. [

] Ethnic minorities, such as the Madhesis and Tharus, say the new constitution, passed in September, ignores their demands and that the Maoists have betrayed them.20

Surface

As a child, I would order the items at Grandfather's desk. Watch, telephone, notepad, pens, old photographs. It was important to catalogue, then lay out flat, all that he kept on this surface. It was also important to correct the photographs: colouring in hair, faded out blues. I was working toward something, something.

Reflection

In entering L.'s desire, I entered into his you. A naming / renaming. The intimacy within. I will see you; you will see me. I will name you; you will name me. We will do this until we break. Then only one of us will carry on.

After Grandfather passed, he also became a you. Suddenly, an open void needing to be filled. Frantically, filling it out with language. I will see you, now that you are no longer here. I would like to see you, though you are no longer here. My you, my love, an absence beating against open water. If once you, Grandfather, were an image of what I left behind (crossing borders, crossing borders), now you, Grandfather, are an image of what is indefinitely gone. Even when I sense your light over a sparrow wing, a sparrow beak. Especially when I sense your light: an unsparing break.

River (ii)

Trying to learn, I begin by thinking back to Grandfather; he would tell me stories each night. I learned the names of places from him: Banaras, Dharan, Bihar.

~

An area of some 5,000 acres . . . of land in Narsahi-Susta area adjoining the Gandak river in West Champaran district has been encroached upon by Nepalese nationals. There is a difference of perception of the boundary alignment between India and Nepal in this area due to shifting of rivers.

— Union Minister of External Affairs, Lokh Sabha, India21

The shifts and winds of the Gandaki — its reasons — fall behind in the conversation.

As per the international case law, the original course of the river would be taken as the boundary, that is, the centre of the old river channel will be the reference point for the boundary. The new course will not be taken into account.

— Medha Bisht, South Asian University22

The voice and movement of the locals in Susta also fall behind. The 265 families that make up Susta contend that "they are part of Ward 4 of Triveni Susta panchayat in Nawalparasi district of Nepal."

Susta has always been a part of Nepal and we are Nepali.

— Aurangzeb Khan, Susta local23

Khan is a vice-principal at Shri Janta Dalit Primary School; his is the only school with a sign that states "Nawalparasi, Nepal."24

~

Grandfather moved from here to there, to another here, to another there. Each had its own placeness, own nameness. He laid out a map through his stories, drawing lines between one here and one there. What became here and what became there seemed to depend on which side of the line he stood on.

~

The border contentions in Susta are augmented during monsoons. Monsoons bleed into floods. Amidst high and incessant rain, the Gandaki expands, and erodes farmland.25

Many need to cross the river: to go to school, to get to markets, to buy eggs.26

We find it very hard to get through the rainy days. India closes the gates of the canal.

— Samsuddhin Miya, Susta local27

Once the canal is closed, the water hardens; getting to the other side toughens.

How many battles must we fight?

— Laila Begum, Susta local28

~

Grandfather liked places lined with eruption. I was advised to visit: Newcastle, Biratnagar, Sikkim. Feeling history rise was important to him. Feeling ghosts rise in the night air, and letting them eat what they pleased. He gathered at the edge of his plate a few grains. He gathered in the afternoon three photographs — his mother, father, grandmother. I have only ever touched their frames.

Stream

In "The Glass Essay," Anne Carson writes,

Perhaps the hardest thing about losing a lover is

to watch the year repeat its days.

It is as if I could dip my hand down

into time and scoop up

blue and green lozenges of April heat

a year ago in another country.

I can feel that other day running underneath this one

like an old videotape29

This is true for any kind of loss, not only of a lover. But it's not quite a videotape. It's the streaming of something heavy and essential below everything that is currently heavy and essential. It's the stream that can erupt and open anytime. It's water.

Everytime I reach below, I come out with everything that came before this. This moment of writing, this moment of walking to the desk and working toward something, something. Which is perhaps why Ali yearns to pull home into his lover's body. If the past washes up against everything, he may as well harness it himself.

Basin

I once used to reach below to belong. But belonging is tenuous. Belonging means origins; origins calcify and become borders. Tracing the fallacies of origins in Canada, Dionne Brand writes,

Too much has been made of origins. And so if I reject this notion of origins I have also to reject its mirror, which is the sense of origins used by the powerless to contest power in a society. The overstrong arguments about "culture," which are made both by defenders of what is "Canadian" as well as defenders of what is labelled "immigrant." These are mirror/image — image/mirror of each other and are invariably conservative. Because they must draw very definite borders . . . to contain their constituencies.30

I am not interested in containment, cages. I want to think beyond solid blocks of ideas.

Belonging, etymologically, has roots in Old English langian; some say it is related to the root of long.31 Long can be traced back to longen "to yearn after, grieve for," which, in its literal sense, means "to grow long, lengthen."32 I can lengthen below the surface, lengthen over a map, but the reach means meeting again the face of tenuousness, its eyes drained. Or thinning over paper, then laying still.

Elsewhere, Brand writes, "in September, and now October, I am unpinned from all allegiances. Of course you're not. But what if I wrote like this? Unpinned."33 Indeed, what if I wrote like this? What if I wrote like this — to you? I unpledge from a civil life, I unpledge. Undo. Come with me, unearth everything that flows. Dip into this river, undo the buttons of my back. Watch me pool into the water, into water. Slip into this blue with me. Unpinned from practicality, bureaucracy, nation-state-country, the doings that lead to our undoings. Come water yourself, and into me.

Shore

If it's not belonging, then what am I searching for? Here — on the page — and elsewhere. Even in the face of origin's fallacies, there's longing. There's seeking through the knowing. Of course I'm not unpinned. Of course history keeps rising. Of course it seeps into this, here. This is a longing so flawed; it compounds into a you that keeps persisting.

With L., I was preoccupied with records. An archive of who we were. Showers against blue tiles; our quips and quirks; reaching for each other mid-sleep, coffee; more coffee; the passing back and forth of the same word, redone and reworked; the lasting press of our never-saids, or half-saids. Here I wanted my memories solid; I was resisting the watery ways in which memories move. Knowing something will end for certain often means wanting to preserve it crystalline.

Grandmother kept everything after we left Nepal. Receipts from old school uniforms, report cards, clothes that no longer fit, scraps and scraps and scraps flowing toward the shore:

B.R.L. MEMORIAL SCHOOL

Kupondol, Lalitpur, Nepal

PROGRESS REPORT

Academic Year [ ]

Class TWO

SUBJECTS MARKS OBTAINED

English II 84

Dictation & Spelling 87

Reading Recitation 85

Writing 68

Nepali II 78

B.R.L. MEMORIAL SCHOOL

Kupondol, [ ], Nepal

PROGRESS REPORT

Academic Year [ ]

Class TWO

SUBJECTS MARKS OBTAINED

English II 84

Dictation & Spelling [ ]

Reading Recitation 85

Writing 68

[ ] II 78

B.R.L. MEMORIAL SCHOOL

Kupondol, [Across the Bagmati], Nepal

PROGRESS REPORT

Academic Year [ ]

Class TWO

SUBJECTS MARKS OBTAINED

English II 84

[ ] & Spelling [ ]

Reading [ ] 85

Writing 68

[Faint tongue] II 78

B.R.L. MEMORIAL SCHOOL

Kupondol, [Across the Bagmati], Nepal

PROGRESS REPORT

Academic Year [ ]

Class TWO

SUBJECTS MARKS OBTAINED

[Clear tongue] II 84

[Discipline] & Spelling [ ]

Reading [ ] 85

Writing 68

[Faint tongue] II 78

B.R.L. MEMORIAL SCHOOL

Kupondol, [Across the Bagmati], Nepal

PROGRESS REPORT

Academic Year [ ]

Class TWO

SUBJECTS MARKS OBTAINED

[Clear tongue] II 84

[Discipline] & Spelling [ ]

Reading [Regulation] 85

Writing 68

[Faint tongue] II 78

Shower

If the blue stretched over your tiles (your tiles) and if the blue stretched over your eyes (your eyes) and if the blue stretched over us (us) under the stream of water and if water met your hands (your hands) as it met my body (my body) and if the mist caught onto the window and seeped into us (us), then thenthe n:

Groundwater

Water interrupts lines. Breaks below their shape and opens the ground, the page, the hard hard thing. I can feel it — I can feel the past — streaming below. But the blue of feeling something without quite knowing what it is looms.

Writing this is, in many ways, a map of its own. I want to trace back to some form of knowing. But it seems I retain very little. I try to trace back to Grandfather. I read, and read, but it sinks someplace unreachable. Writing this feels like I'm doing something wrong. The wide gash of distance between here to there and the wide gash of time between then and now bind into a gap I am compelled to fill, though I know I can't. My learning feels insufficient — my tumid anxiety, and its quest for mastery. What I hold in my hands feels insufficient.

What I hold:

A faded tag on a pair of trousers Grandmother kept: [ ]

A hefty photo album with illegible names and years: [ ] on [ ]

Rupee notes, softened and creased by the years: नेपाल राष्ट्र बैंक रुपैयाँएक

Scraps andscraps andscra

Which is perhaps why I want to write about water. I keep thinking that thinking in this way will get me somewhere. Get me to move with the gap. Get me to break the page, the lines marked on maps to indicate time and distance.

For a year now, I've carried around a book called Understanding the Maoist Movement in Nepal. My reading is inflected with half-memories, half-mirages. My colonial education would say that I am failing to be an objective student of history. I am writing out lines that stick, scraps and words that feel as though they can rise to something, something. Then, I am putting them together:

doctrine of armed struggle...foot soldiers...Gorkha, Rolpa, Rukum...their older sister...a passport picture-negative...in whole villages...the western hill districts...there are no men...absconders...fled into the surrounding jungles...melted into the cities...the presence of women in propaganda...tryst...mid-western villages...Maoist epicentre...the harvested fields...idyllic...dotted with haystacks and crops of mustards...one gets the feeling that the villages...are emptying...dead of the night...some of the armymen...visibly drunk...When the dogs bark at night we know that either the Maoist or the army have come to the village...her daughter...her eyes...filled with poems...a vast adult melancholy34

Watertongue (i)

I want a language that seeps. I want a language that seeps.

Deluge

In dreams, I circle a page. I gather words from its water, water speaking to me:

I split at the edge of my own ice. No brine here, just the bitter cold of my bite. Later down, a frostfull lake, then floods.

But each ripple has a tongue: becomes sound, becomes word. Come closer, then salt. Hint of zephyr, here's my letter:

Feel what is shaking beneath you, feel me. Feel the fallen the felled, dropping the dropped. No time to catalogue. Find a roof, I will steal a roof. The wash of my water coming toward anything open. Anything at all.

In the morning, stepping over bones. This is not a graveyard. This is watereddown death.

If the blue lines of what you see don't say a thing, there isn't a thing, not a thing.

Kiss me on a cup, the dirt, on the treelined brinkandbind sign. Keep out means nothing when you can seep through.

In the morning, I say I didn't mean to hurl. I wanted to show what they've done to me. I showed it to the wrong crowd.

Cobalt morning: I collect lines, call it an almanac. A new record of time, a thing to anticipate:

Heavy Rain and Floods in Southern Central Areas Leave 4 Dead, Houses Destroyed

10 Dead, 6 Missing After Heavy Rain Triggers Landslides

Over 30 Dead or Missing After Floods and Landslides in Sindhupalchok

12 Dead, 41 Missing After Floods and Landslides in Baglung

6 Dead, 11 Missing After Floods in Achham

Dozens Dead or Missing After Heavy Rain Triggers Floods and Landslides

Deadly Floods and Landslides in Gandaki and Bagmati Provinces

Floods and Landslides Cause Death and Damage in Western and Central Areas

3 Killed in Palpa Landslide

Landslide in Parbat Leaves 8 Dead

Deadly Landslide in Baglung

Dozens Dead After Heavy Monsoon Rains35

But step in. This isn't a dream. Look at the footsteps: bare, bare, bruised. I've been writing to you since you left, my watery reach only going so far. Yet you've come. You've come because you've heard where I've spilled. I watched heads and hides split off, an open wide blue. Floods, they say when I get like this. You've come because I've changed course, right through Susta. You must know, I don't like to be hushed, hulled. I don't mean to harm; I am trying to get back. Into earth, under too: there's an open hand waiting for me: I must feel its palm again: I must catch myself against its lines, frayed like branches.

There's a mynah flicking its wings against a breaking tip.

There's a mynah, you see — you must.

Watertongue (ii)

I want a language that seeps. A language that lets history rise. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass Robin Wall Kimmerer writes,

A bay is a noun only if water is dead. When bay is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the [Potawatomi] verb wikwegamaa — to be a bay — releases water from bondage and lets it live. "To be a bay" holds wonder that, for this moment, the living moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers. Because it could do otherwise — become a stream or an ocean or a waterfall, and there are verbs for that, too. To be a hill, to be a sandy beach, to be a Saturday all are possible verbs in a world where everything is alive.36

To be blue

To be colour

To be page

To be its flowing water

To be I

To be you

To be and redo

To be shore

To be flood

To be history

To be rain

To be fall

To be gray

To be water, to speak back to me.

Etymologically, water can be linked to the Proto-Indo European wod-or. Linguists trace this back to the root words ap- and wed-. I read:

The first (preserved in Sanskrit apah as well as Punjab and julep) was "animate," referring to water as a living force; the latter referred to it as an inanimate substance. The same probably was true of fire.37

There are languages within which water speaks. I am trying to let water speak, I am trying to listen. In the mornings I ask: What does the water know, what does the water remember? Beating against my skin, through the faucet, the drain. I am trying to listen to a former I — a you. A you a lump against my larynx. A you, she speaks back, refuses transcription. A you sweeping into the wind of water.

To my naive ears, apah echoes "grandfather": Greek pappa "o father," pappas "father," pappos "grandfather."38 Though not linked etymologically, I sink into this misconstrual for the rest of the day. If, for Ali, you is the container of yearning, water is mine. Or rather, water is where they all rise. You: Grandfather, home, lover, former I.

Apah

In August, I dream I am walking up the stairs. Ochre, umber, the stairs tipping toward something, something. You are there. I walk into the room; I find apah pressed into the pages of a book. Yours. When it falls open, the door toward water creaks. I walk in. Lines sunk and blue into history, the air was, a wisp a wilt. You keep count of the books you read, a shelf against paling memories. Apah keeps water alive. It keeps it so I can step in. I step in and you flow out, verdigris:

[

]

[

]

[

]

[

[

]

[

Snigdha Koirala (@__snigdha) is a writer/poet based in London. Her work has previously appeared in Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Gutter Magazine, Wildness, and others. A graduate of NYU's Center of Experimental Humanities, her research explores, amongst other things, the relationships between water, opacity, language, and affects. Her debut chapbook, Xenoglossia, is out with Wendy's Subway.

References

- Snigdha Koraila, Xenoglossia, Wendy's Subway (2021), 26.[⤒]

- Vicente Rafael, Motherless Tongues: The Insurgency of Language Amid Wars of Translation, Duke University Press (2016), 6.[⤒]

- Priyanka Kumari and Ramanek Kushwaha, "Sugauli Treaty 1816," International Journal of History 1, no. 1 (2019): 42-47.[⤒]

- Anil Giri, "Original copies of both Sugauli Treaty and Nepal-India Friendship Treaty are missing," Kathmandu Post, August 13, 2019, https://kathmandupost.com/national/2019/08/13/original-copies-of-sugauli-treaty-and-nepal-india-friendship-treaty-are-both-missing.[⤒]

- Nidhi Jamwal, "As a river changed its course, a village on the India-Nepal border became disputed territory," Scroll.in, Mar 19, 2017, https://scroll.in/article/831576/as-a-river-changed-its-course-a-village-on-the-india-nepal-border-became-disputed-territory.[⤒]

- Agha Shahid Ali, A Country Without a Post Office (New York: Penguin Books, 2013), 15.[⤒]

- Ali, A Country, 44.[⤒]

- Agha Shahid Ali, A Nostalgist's Map of America (New York: WW Norton, 1992), 65.[⤒]

- Ali, A Nostalgist's Map, 65.[⤒]

- Ali, A Country, 77.[⤒]

- Douglas Harper, "revolution (n.)," Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=revolution.[⤒]

- "From the archive: April 9, 1990: Nepal king bows to protests," The Guardian, April 9, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/09/nepal-king-birendra-democracy-1990.[⤒]

- John Whelpton, A History of Nepal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 117-119.[⤒]

- "From the archive: April 9, 1990: Nepal king bows to protests." The Guardian, April 9, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/09/nepal-king-birendra-democracy-1990.[⤒]

- Mukesh Pokhrel, "One moment 30 years ago today," Nepali Times, April 9, 2020, https://www.nepalitimes.com/banner/one-moment-30-years-ago-today/.[⤒]

- Pokhrel, "One moment 30 years ago today."[⤒]

- Ali, A Nostalgist's Map, 65.[⤒]

- Ali, A Country, 90.[⤒]

- Whelpton, A History of Nepal, 118.[⤒]

- Gyanu Adhikari and Saif Khalid, "Nepal: The Maoist Dream," Aljazeera, 2016, https://labs.aljazeera.com/nepal-maoist/Nepal_The_Maoist_Dream.pdf.[⤒]

- Jamwal, "As a river changed its course." [⤒]

- Jamwal, "As a river changed its course."[⤒]

- Jamwal, "As a river changed its course."[⤒]

- Jamwal, "As a river changed its course."[⤒]

- Prasiit Sthapit, "Change of Course." LensCulture, https://www.lensculture.com/articles/prasiit-sthapit-change-of-course.[⤒]

- Sthapit, "Change of Course"; Rekha Bhusal, "Locals of Susta using boats." myRepublica, November 24, 2019, https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/locals-of-susta-using-boats-to-cross-narayani-river-since-ages-due-to-lack-of-bridge/.[⤒]

- Bhusal, "Locals of Susta using boats."[⤒]

- Prasiit Sthapit, "Change of Course."[⤒]

- Anne Carson, "The Glass Essay," Glass, Irony and God (New York: New Directions, 1995), 8.[⤒]

- Dionne Brand. A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging (Toronto: Vintage Canada: 2001).[⤒]

- Douglas Harper, "belong (v.)," Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/belong#etymonline_v_8290.[⤒]

- Douglas Harper, "long (v.)," Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/long?ref=etymonline_crossreference#etymonline_v_12412.[⤒]

- Dionne Brand, The Blue Clerk: Ars Poetica in 59 Versoes (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 43.[⤒]

- Deepak Thapa, editor, Understanding the Maoist Movement in Nepal (Kathmandu: Martin Chautari/Centre for Social Research and Development, 2003).[⤒]

- FloodList, 2008, http://floodlist.com/tag/nepal.[⤒]

- Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 54.[⤒]

- Douglas Harper, "water (n.1)," Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/water#etymonline_v_25556.[⤒]

- Harper, Douglas, "papa (n.)," Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/papa#etymonline_v_3099.[⤒]