For Speed and Creed: The Fast and Furious Franchise

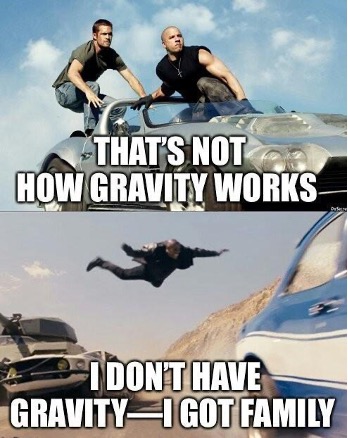

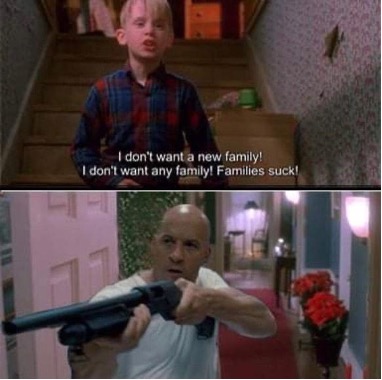

At this point, The Fast Saga's emphasis on family has become a running joke.

In the explosively popular new TV series Abbott Elementary, when eager-beaver teacher Janine (Quinta Brunson) insists to her colleagues, "We're family," her boss — the often-disparaging but undoubtedly witty Ava (Janelle James) — responds, mockingly, "Enough with that Dominic Toretto rhetoric." Janine, cowed, stutters out, "Th-There's a reason that there are nine of those movies."1 Although the scene quickly moves on, Ava's joke is telling — the idea of workplace family has become synonymous with Dom's (Vin Diesel) character and the whole ethos motivating The Fast Saga.2 Janine's response is equally telling. Over two decades that seem to have moved as quickly as our beloved street racers do — with technology transforming from the flip phones and floppy discs of The Fast and the Furious (2001) to the biometric monitors that appear in F9 (2021), and world events speeding by just as fast — there is a reason that this franchise has been able to endure, movie after movie, continually dominating the box office.3 The one constant, and the heart of the franchise's persistent appeal, is Dom's franchise-defining rhetoric of kinship, distilled in his catchphrase: "I don't got friends, I got family."4

Through that sense of kinship, The Fast Saga offers an ethics of care, alluring in the face of an increasingly individualistic milieu. The later films further build on this tradition by demonstrating how memory is entangled with such an ethos. Although care ethics has been considered a feminist strand of philosophy because it centers traditionally feminine responsibilities (like motherhood) and aims to counter the harms of patriarchal power, I do not claim The Fast Saga to be a feminist masterpiece, or even as intentionally engaging with this tradition. Rather, I am interested in uncovering the traces of care ethics that appear in this franchise and understanding their impact.

Making Kin

In summarizing care ethics, Carol Gilligan — whose psychological study In A Different Voice largely sparked the tradition — describes a "paradigm shift" based in the "recognition that empathy and caring are human strengths."5 Rather than prioritizing the individual, care ethics asks us to consider humans first and foremost as "responsive, relational beings."6 In her book on the topic, Virginia Held explains how care ethics seeks to recognize the way we are always already embedded within contexts — whether familial, social or historical — and so always already endowed with responsibilities for and to others. Traditional moral theories from Hobbes to Kant to Rawls, which present people as "self-sufficient independent individuals" and then proceed to glorify self-sufficiency, independence and individualism, have distorted our reality.7 Instead, we are fundamentally "relational and interdependent" — an actuality that The Fast Saga successfully captures in its insistence on family as well as in its injunction against those who don't respect such bonds.8 Only bad guys work alone — but even they become redeemable if they start valuing togetherness. Characters like Brian (Paul Walker), Vince (Matt Schulze), and Letty (Michelle Rodriguez) are criticized precisely because they seem to betray the family — as when, after his work as an undercover cop sends Dom on the run, Mia (Jordana Brewster) sarcastically snarls at Brian, "I'm so sorry you ripped my family apart."9 But once these characters return to the fold, risking their wellbeing to do so, they are welcomed back earnestly. After Vince saves Mia, Dom brings him back onto the job because "there's always room for family."10 And even Deckard Shaw (Jason Statham), the antagonist of Furious 7 (2015),becomes humanized by his efforts to save Dom's son and thus keep the family whole in The Fate of the Furious (2017).

In centering care for the other, the care ethics model typically sees itself as undercutting ideologies that promote violence against the other. These films manage to present both simultaneously, foregrounding care among the family but violence outside it — but anyone can join (or rejoin) the in-group by practicing care for its members. Lines between who is and isn't family constantly shift; kinship is ever fluid.

That kinship notably extends beyond mere blood relations. The introduction of Dom's and Mia's brother Jakob (John Cena) in F9 makes it especially clear that their familial bonds are substantiated by care for one another rather than by blood; despite being blood-related, Jakob's presumed lack of care has excised him from their family altogether. The terrorist supervillain Cipher (Charlize Theron) deeply misunderstands the way these characters understand kinship, admonishing Dom, "This idea of family that is so core with you, that rules your world, it's a biological lie. You don't have to accept it. I don't."11 But Dom's idea of family is not biologically based: family is always a choice. In The Fast and the Furious, as Brian struggles to decide between trusting the Torettos et al. and his LAPD bosses, his supervisor tells him that "there's all kinds of family, Brian. And that's a choice you're going to have to make."12 Again and again, when the rubber literally hits the road, Brian chooses Dom, Mia and the rest of the crew. The films therefore affirm that you don't have to accept biology, but you can (and should) choose family.

Cipher is not the only antagonist who practices the kind of individualism that the family rejects (and other action movies tend to reaffirm — see contemporaries like the Mission Impossible and Bourne franchises). Owen Shaw (Luke Evans) from Fast & Furious 6 (2013) similarly fails to understand interpersonal bonds as valuable, as he reveals when he announces a team is just "pieces you switch out until you get the job done" and that Dom's belief otherwise is his weakness.13 Owen Shaw's eventual defeat thus further reifies The Fast Saga's visualization of kinship as an asset as well as a necessity. That his brother, Deckard Shaw, seeks first to avenge Owen in Furious 7 and then later convinces him to help save Dom's son in The Fate of the Furious suggests that family has its appeal, even for this sometime-poster-boy for self-reliance. Donna Haraway similarly sees such non-normative kinships as an asset, useful for challenging exploitative systems.14 She advocates that we "make 'kin' mean something other/more than entities tied by ancestry or genealogy," a redefinition that ultimately "can stretch the imagination and change the story."15 Haraway hardly means to point us toward The Fast Saga; even as these filmsundercut systems of policing and capital by bending and breaking their laws, they also gleefully participate in money-making, patriarchy (there is no question that Dom always sits at the head of the table, quite literally so at every cookout), the wanton consumption of fossil fuels and imperialistic uses of space (see Nichole Misako Nomura elsewhere in this cluster for more). That such exploitations coexist alongside this non-normative kinship both signals the complexity of these films and poses questions about the care ethics model. If we read these films as an example of care ethics in action, it becomes evident that recognizing our interdependence and expanding our understanding of familial belonging does not necessarily or automatically address all violent ideologies at once. Nonetheless, Haraway's insights on the power of non-normative relationality resonate in these films.16 These characters do not need to share ancestry, genealogy, or even culture to function as a family. Instead, they share a dedication to one another that supersedes rival racers, law enforcement, terrorists and even death.

Making Memories

The careful way Furious 7 and the ensuing filmsconstruct Paul Walker's memory via their characterization of Brian O'Conner reveals how wielding memory can demonstrate care amongst kin. Care ethics philosophers do not typically list memory as an act of care, but it slots right in, both in helping to build community and sustaining it in the face of loss. In addressing Walker's 2013 death, Furious 7's final scene reveals much about the care with which his film family approaches his memory. To start, this scene makes no sense if you don't know that Paul Walker has died. Tej (Ludacris) urges Roman (Tyrese) to admire Brian playing with his son, and Letty comments "that's where he belongs." Dom agrees, "home — where he's always belonged."17 The suddenly mournful music transitions into the iconic opening notes of the chart-topping "See You Again" written for Walker's death.18 All these emotional cues seem strange in a world in which Brian keeps living, playing with his children, and regularly attending barbeques. It is a moment that transcends the fictional universe in which The Fast Saga exists, clearly designed to confront Paul Walker's loss. Dom may insist that "it's never goodbye"19 and the lyrics may maintain in every chorus that "I'll tell you all about it when I see you again,"20 but there is no doubt that this is Paul's and Brian's send-off. And yet such overtures also make clear that death is hardly a firm separation or final ending; instead, it appears as merely a median — literally, as we watch Brian's white car branch off from Dom's onto a separate road, going in a new but parallel direction (I never said the symbolism was subtle).

Making this film — dedicated "For Paul" — and the series more broadly into a vehicle for constructing Brian's/Walker's legacy is precisely what maintains that connection.

As Dom and Brian race one last time and the music plays, the film segues into a trip down memory lane for Brian's character. Wiz Khalifa raps, "How can we not talk about family when family is all that we got?"21 as viewers re-watch key scenes featuring Brian. Quieter displays of kinship are conspicuously favored over momentous stunts — we witness the moments when Brian first gives Dom his car (the act that sets them on this path), when Brian lets Dom drive away (the act that repairs their bond), when Agent Hobbs (Dwayne Johnson) tells the crew that they are pardoned (the act that enables them to protect their families), when Dom tells Brian they're "home, sweet home" as they drive up to a drag race, when various groups pray around various tables, and so many hugs.22 These are all scenes of building community and of finding home — where, Letty and Dom have just told us, Brian has always belonged.

Meanwhile, Dom/Diesel reflects on his relationship with Brian/Walker. Pausing dramatically, he determines, "I used to say I lived my life a quarter mile at a time. And I think that's why we were brothers. Because you did, too."23 This phrasing solidifies the films' expansive notion of kinship; Dom and Brian's brotherhood rests in their shared values and common passions, not in any particular genetic, ethnic, or class overlap. Their bond has superseded those categories, given that the two men share no genes and have different ethnic, cultural, and economic backgrounds. As the movie closes, Dom adds, "No matter where you are, whether it's a quarter-mile away, or halfway across the world . . ." and then, as we wait in suspense to hear the end of this sentence, we see interspersed the iconic scene from Fast Five (2011) in which Dom holds up his Corona (see Christian Giallombardo Long elsewhere in this cluster on that imagery) and announces: "The most important thing in life will always be the people in this room." Family's importance thus intervenes in Dom's admission that Brian will now be apart from him, and yet we quickly find that Brian remains one of the people in that room, forever. Flashback over, Dom finishes his sentence: ". . . You'll always be with me. And you'll always be my brother."24 The films' final images of Brian/Walker remind us of his commitment to and belonging within "la familia."

By contrast, in Fast & Furious 6, Letty is disgusted that Owen Shaw cares so little when his crew member dies, sardonically commenting, "that's a great eulogy."25 Shaw's eulogy had implied that this teammate deserved to die, noting only that "he made a mistake. If you make a mistake, you pay the price."26 For Shaw, unlike the Fast family, death is not a new road but a dead-end. There is no more to be said, no more meaning to be made or care to be offered. There is also no hope for a U-turn, no chance at redemption or reabsorption into the team, because Shaw presents death as a justifiable cost for any mistake.

We thus see the difference between a eulogy given by someone who sees his team as machinery, and one given by a family. The family's eulogy emphasizes its members' care for Brian and Brian's reciprocal care for them, encoding his memory as first and foremost a father, husband, friend, brother. At this point in the films, Brian has made mistakes — like working for the police or letting Letty go undercover — but has always been welcomed back into the fold once he displays his continued concern for the others. This family refuses to let go of its own.

Before Dom and Brian prepare to risk their lives in Fast & Furious, Mia wonders, "How do you say goodbye to your only brother?" Dom simply responds, "You don't."27 Dom has many brothers, including a biological one, but in this final scene, as he calls Brian — and Paul — his brother, he shows us what it means to refuse to say goodbye.

Significantly, Brian is written out of subsequent scripts by becoming essentially a stay-at-home father, a literal caretaker. When Mia rejoins the crew in F9, she assures Dom that "my kids and yours are in the safest hands possible," which means, as Letty clarifies, "with Brian."28 Brian's character arc shifts away from the death-defying driving sequences but nonetheless remains firmly within the series' real centrifugal force —the family — and, as Mackenzie Streissguth points out elsewhere in this cluster, operates as its own sort of defiance of death. In fact, for a character who begins the saga craving a bond like the one he sees between Dom and company, Brian's final role as chief homemaker feels like a culmination of sorts; Brian is not just in the family but forever its home.

To create this memorial, the films released after Walker's death tweaked prior plotlines. For example, in Fast Five, Dom told Brian to leave him to face his gun-toting pursuers alone because "you're a father now." But Brian insists on hiding out near Dom and eventually saves his life. 29 Similarly, at the beginning of Fast & Furious 6, although Brian and Mia decide "our old life is done" after their baby is born, Brian still joins Dom's mission to rescue Letty because, as Mia asserts, "We're family. If we got a problem, we deal with it together . . . . You're stronger together. You always were."30 Here, Mia affirms the well-established value of the collective in these films, in which kinship is the ultimate strength. But in the next movie, Mia's mindset has shifted. She again tells Brian to accompany Dom to protect their family, and yet also mandates, "after this, we're done."31 And they are. In The Fate of the Furious, when Dom seemingly goes rogue and Roman laments, "Brian would know what to do," Letty conveniently explains their absence: "We can't bring Brian and Mia into this. We agreed on that."32 In F9, we return to this premise, with Dom telling Letty that "Brian and Mia got out of the game when they became parents." After earlier movies proclaimed that Brian and Mia would stick with Dom despite and because of the danger he faced, the later movies had to revise this expectation to explain Brian's absence while also keeping him alive.

As a result, Furious 7 intentionally reconstructs Brian's character to make him the paragon of family values. At one point, Dom even says to him, "Want to know the bravest thing I ever saw you do? Be a good man to Mia. Being a great father to my nephew Jack. Everyone's looking for the thrill, but what's real is family. Your family."33 This image of Brian/Walker not only confirms the value of family but also shows how memory becomes a tool in it. We might turn again to Donna Haraway, who argues that the act of assembling together — "making kin and making kind" — reconstitutes, recuperates and recomposites the spaces that we all must share so that we can better live, better mourn and better die.34 In turn, The Fast Saga's characters show how the bonds we form — the ways we care for one another — allow us to achieve such possibilities.35 Just as we watch the crew (re)assemble each movie, and (re)pledge themselves to one another, we also watch how they (re)compose Brian's character so as to effectively mourn Paul Walker's loss.

Perhaps coincidentally, perhaps intentionally, during Furious 7 the family attends a funeral of one of their own. At it, Dom reflects that "to live in the hearts of those we leave behind is not to die."36 This claim to immortality reappears at the climax of F9, when Dom remembers his own father teaching him that "cars like this are immortal . . . just like a family, Dom. Build it right, you take care of it, it'll run beyond you."37 In taking care of Brian O'Conner, his family helps Paul Walker live on, one-quarter mile at a time.

Maggie Laurel Boyd (@mlboyd23) is a 5th year PhD Candidate and Graduate Teaching Fellow at Boston University. She also works as a Writing Fellow at BU's Educational Resource Center and in BU's Fellowships Office. She is currently writing a dissertation on contemporary U.S. and Irish narratives of healing, using a blend of trauma theory, gender theory and queer theory. Her research explores the ways in which texts represent and re-imagine healing amid and against an increasing tendency to pathologize experience. She has been a devoted fan of the Fast and Furious franchise ever since her brother Brendan Boyd - a Fast and Furious aficionado - first sparked her interest in the films.

References

- Abbott Elementary, season 1, episode 8, "Work Family," directed by Jay Karas, written by Quinta Brunson, Justin Tan, Brittani Nichols, et. al., featuring Quinta Brunson, Tyler James Williams and Janelle James. Aired February 15, 2022, in broadcast syndication. [⤒]

- See Roxane Gay, who writes in her summary of the films: "under Dom's leadership, they are family (family is everything)." Or, see Jen Yamato, who proclaims in her review for The Fate of the Furious that "the record-breaking franchise, built on physics-defying stunts and fervent fan loyalty across the globe, is also fueled by the one not-so-secret idea more potent than a well-timed blast of nitrous oxide: family." Roxane Gay, "Not-So-Guilty Pleasures: The Fast and the Furious," The Toast, July 10, 2013; Jen Yamato, "How family - and diversity - fueled the $4 billion 'Fast and Furious' franchise to historic box office heights," The Los Angeles Times, April 17, 2017. [⤒]

- The Fast Saga makes the list for both highest grossest film series — with its 10 associated films bringing in a whopping $6.6 billion dollars at the box office — and longest running, currently at 19 years and 10 months.[⤒]

- Furious 7, directed by James Wan (Universal Pictures, 2015).[⤒]

- Carol Gilligan, "Moral Injury and the Ethic of Care: Reframing the Conversation about Differences," Journal of Social Philosophy 45, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 89.[⤒]

- Gilligan, "Moral Injury," 90.[⤒]

- Virginia Held, The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political and Global (London: Oxford, 2006), 13.[⤒]

- Held, Ethics of Care, 13.[⤒]

- Fast & Furious, directed by Justin Lin (Universal Pictures, 2009).[⤒]

- Fast 5, directed by Justin Lin (Universal Pictures, 2011).[⤒]

- The Fate of the Furious (F8), directed by F. Gary Gray (Universal Pictures, 2017).[⤒]

- The Fast and the Furious, directed by Rob Cohen (Universal Pictures, 2001).[⤒]

- Fast & Furious 6, directed by Justin Lin (Universal Pictures, 2013).[⤒]

- Jason Smith's study of Black characters in cinema — which includes 2 Fast 2 Furious in its corpus of data, though never discusses it explicitly — discusses how "social isolation . . . is unthreatening to White heteronormativity" and thus a single Black character is often symbolic of a colorblind ideology rather than a color conscious one (784). The fact that The Fast Saga presents a multi-cultural cast in a tight-knit group might thus threatens White supremacy, though it remains firmly heteronormative. See Jason Smith, "Between Colorblind and Colorconscious: Contemporary Hollywood Films and Struggles Over Racial Representation," Journal of Black Studies 44, no. 8 (November 2013): 779.[⤒]

- Donna Haraway, "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin," Environmental Humanities 6 (2015), 161-162.[⤒]

- Though it is not within the scope of this paper, the relationships with cars in this series are suggestive of cyborg technologies and hybrid identities, too.[⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- Samantha Highfell, "Charlie Puth talks writing 'See You Again' for Paul Walker's goodbye," Entertainment Weekly, April 7, 2015; Andres Tardio, "Wiz Khalifa Opens Up About Writing Emotional Paul Walker Tribute 'See You Again,'" MTV News, April 15, 2015. [⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- Wiz Khalifa, "See You Again (feat. Charlie Puth)," Atlantic Recording Corporation, Track #1 on "See You Again (feat. Charlie Puth)," 2015.[⤒]

- Khalifa, "See You Again."[⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- Fast & Furious 6.[⤒]

- Fast & Furious 6.[⤒]

- Fast & Furious 4. The fact that Mia is later revealed to have another brother is a great example of the saga's disregard for continuity. [⤒]

- F9: The Fast Saga, directed by Justin Lin (Universal Pictures, 2021).[⤒]

- Fast 5. [⤒]

- Fast & Furious 6. [⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- The Fate of the Furious.[⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- Haraway, "Anthropocene," 161. [⤒]

- The film itself is one such space of possibility. Vin Diesel shared in a 2015 award acceptance speech that the cast didn't want to return to filming at first after Walker's death, but "the love of everyone combined . . . saw us through." In this framing, the sense of connection between cast and from fans actually enabled the film's production. Lisbeth Klastrup analyzes Vin Diesel's public Facebook page and the patterns of his posts mourning Paul Walker, determining that he thereby creates a community of mourning, inviting his fans to join him in commemorating Paul and thus "keep[ing] the memory of that precious friend alive in perpetuity." I suggest that his movies achieve something similar, especially in these scenes that transcend their fictional universe by clearly addressing Walker's death rather than Brian's exit. See Lisa Klastrup, "Death and Communal Mass-Mourning: Vin Diesel and the Remembrance of Paul Walker," Social Media & Society 4, no. 1 (2018).[⤒]

- Furious 7.[⤒]

- F9.[⤒]