For Speed and Creed: The Fast and Furious Franchise

At a time when working- and middle-class individuals and families are faced with decreasing social and economic mobility, the popular Fast and Furious franchise (The Fast Saga) offers audiences an expanding cinematic fantasy of global mobility and newfound wealth. This type of globetrotting movement and wealth accumulation is normally reserved for members of the so-called "transnational capitalist class," who are the owners and executives associated with multinational corporations and private financial institutions.1 For decades now, consecutive generations of working- and middle-class Americans have found it harder to climb the economic ladder of mobility by earning higher incomes than their parents. The main culprits are stagnating wage growth, and an income distribution that has shifted by twenty percent to the upper class over the last fifty years.2 African Americans and Native Americans, moreover, experience lower upward mobility than white, Hispanic, or Asian Americans.3 Zygmunt Bauman argues that one of the defining characteristics of present-day economic inequality is not the domination of the bigger over the smaller, but rather of the quicker over the slower in the workforce. The people who are able to move fast and be flexible in responding to changing market demands tend to dominate over people whose lack of resources precludes such dynamic responsiveness, and so existing inequalities compound.4 The Fast Saga's Dominic "Dom" Toretto (Vin Diesel), a former convict and automotive shop owner, and his "family" of multiracial and multicultural street racers, auto mechanics, and computer geeks are unlikely avatars of economic mobility. But, because of their extraordinary ability to perform high-speed truck and cargo hijacking, along with their relationship with Brian O'Conner (Paul Walker), a Los Angeles police officer turned FBI agent turned fugitive, Dom and his crew are fast, flexible, and mobile, capable of executing million-dollar heists and covert international missions for government agencies. The Fast Saga therefore offers audiences a working class male fantasy of global social and economic mobility, as it delves into the spatial politics of urban environments, iconic architecture, and transnational networks.

The first films in The Fast Saga were about street racing and urban crime, but since the Fast & Furious (2009) the franchise has transitioned into a full-fledged action series — dominated, in accordance with the conventions of the genre, by a narrative emphasis on spectacular fights, chases and explosions, featuring computer-generated special effects and stunt work. Fast & Furious begins with the type of accelerated chase sequence that has come to define the primary action of the franchise. After five years on the lam, Dom and his new crew, consisting of his girlfriend Letty (Michelle Rodriguez), Tego Leo (Tego Calderón), Rico Santos (Don Omar), Cara (Mirtha Michelle) and Han Lue (Sung Kang), are hijacking fuel tankers in the Dominican Republic, using heavily modified 1967 and 1988 Chevrolet trucks and a 1987 Buick Grand National. After Dom and Letty briefly converse in the Buick, Letty climbs out the passenger window and onto the hood of the car (fig. 1). Dom radios back to the other two cars before initiating the operation, which will involve uncoupling two tanks at a time and towing them away on the pickups while the tanker truck is still in motion. Dom distracts the tanker driver by driving irregularly in front of the truck but close enough for Letty to jump onto the tanker to begin separating the tanks. Hooking the first tanker up to a pickup goes smoothly, but during the second operation the tanker driver sees Letty on top of the tanker in his mirror and swerves back and forth in an attempt to dislodge her and preserve his load, making Letty and the passenger of the still-connected pickup truck lose their balance. On a sloping road, Letty is able to release the last two tankers and Dom's quick driving maneuvers enable the second pickup to drive its load away. With the end of the road in sight, the driver dives out of his truck and Letty jumps into Dom's car just in time before the remaining tankers separate and slide in front of them. Dom drives safely through a gap between the bouncing and exploding tankers.

This action sequence not only illustrates the superb driving and physical prowess of Dom and his crew but also expresses a spectacle of "physical mastery"5 and a fantasy of empowerment for film spectators. According to Lisa Purse, in action films the hero's body has the capacity to achieve such physical mastery over differing environments, people, institutions, and criminal organizations. The Fast Saga offers precisely these "images of physical power" that serve "as counterpoint to an experience of the world defined by restrictive limits."6 Through sensorial connection with these action bodies, the film spectator can imagine their own fantasized escapes from constricted reality. Purse asserts that this mastery is often realized only after a momentary loss of the hero's control over the situation so that we can feel this defeat just before mastery is finally attained.7

The Fast Saga extends this fantasy-induced sense of empowerment through the connection between the hero's (driver's) body with his car. Tim Dant argues that the bond between driver and car can be understood as an "assemblage," a form of "social being" that generates a set of social actions associated with the car, including driving, parking, racing, transporting, and others.8 Dant states that this driver-car assemblage is distinct from other terms coined to describe a human-machine intersection ("cyborg," "hybrid") primarily because the assemblage separates when the driver leaves the car and it can be re-assembled again based on the availability of fresh cars and drivers.9 During a time when the automobile is said to be losing its generational popularity with young people,10 The Fast Saga affirms and celebrates the intimate relationship between the driver and his high-performance, internal-combustion car as a primary source of physical mastery over a bewildering range of environments, including congested city streets, mountainous roads, icy Arctic flats, and even outer space. The Fast Saga's fetishization of extreme driving and super-modified vehicles reflects and reinforces the twentieth-century western cultural association between young men and fast cars — the expression of manhood through automotive speed and power that Sarah Redshaw terms "combustion masculinity."11

The foregrounding of Dom and his crew's driving talents in these films leads to spectacular (if highly improbable) action sequences, invariably causing massive destruction to public and private property, especially cars. Purse asserts that one of the main appeals of action cinema is the "fantasy of mapping — and sometimes destroying — urban space through assertive, self-directed movement."12 Locations such as Azerbaijan, Brazil, Cuba, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Spain, and the United Arab Emirates provide The Fast Saga's action heroes with distinct challenges as they must quickly learn to negotiate, appropriate, and master these diverse spaces. In moving among these geographical areas The Fast Saga not only connotes globalization, but also illustrates how the "physically active body" of the action hero can navigate the tactile environments of a diverse range of spaces.13 In Fast Five (2011), instead of simply stealing a crime lord's $100 million from a vault in a guarded Rio police station, Dom and Brian attach their modified 2010 Dodge Charger SRT-8 cars to the enormous vault and drag it out of the station. Directed by Mia Toretto (Jordana Brewster), Dom's sister, Dom and Brian are chased through Rio's busy downtown by an army of police cruisers. During the chase, the cops shoot at Dom and Brian, and the vault destroys countless cars, property, and even a bank. Before they reach the bridge, Dom unhooks Brian's car and proceeds to battle it out with the crime lord's men. Once the crime lord is killed, Hobbs (Dwayne Johnson), a federal agent, appears and agrees to give Dom and Brian a 24-hour head start before he begins looking for them, but they must leave the vault. Since Dom and Brian secretly switched out the vault during the chase, Hobbs opens the vault only to find it empty. The team divides up the loot and disperses across the world to enjoy newfound prosperity and enhanced social and economic mobility.

While Dom's crew has expertise in breaking into buildings and hacking into security systems, their principal tool for tactically intervening into state and institutional spaces is the customized street race car, an emblem of Dom's working-class, car culture background and his desire to live life "a quarter-mile at a time." Though street racing cars and performance driving skills may seem anachronistic in the twenty-first century — and especially unlikely as tools to be deployed in covert missions for government agencies — The Fast Saga creates fantasy narrative scenarios in which these skills and abilities are critical to the success of the crew's increasingly audacious operations. As Ulf Mellström maintains, "embodied practical knowledge" of cars, shared among men, is a critical site for understanding how masculinity is produced, maintained, and sanctioned.14 Unlike college-trained specializations in information technology and data encryption, the skills that matter in The Fast Saga are ones that appear accessible to many working class American men. Beyond reinforcing the association between cars and masculinity, the primary fantasy at work in the film franchise, then, is that working-class men (and women) experience great social mobility and wealth accumulation in the global economy.

Besides providing a sense of physical mastery and empowerment, action films also offer us an understanding of space, especially urban space. As the twentieth century progressed, ever greater areas of land and space came under the domain of capitalism. This type of control created legal spatial constrictions that established borders to regulate and restrict individual access to and movement across places and spaces. Drawing on the theoretical works of Henri Lefebvre and Michel de Certeau, Nick Jones argues that action films serve as expressions of frustration and dissatisfaction with the spatial constrictions in urban living.15 Just as de Certeau traces the tactics and strategies of a pedestrian walking through bureaucratically organized and instrumental city spaces, Jones maintains that action heroes tactically negotiate, appropriate and master, at least temporarily, facets of state and corporate controlled spaces to accomplish their missions. Through their embodied actions and movements, the pedestrian and action protagonist alike transform alienating, abstract spaces into places, filled with meaning.16 In doing so, the action protagonist's movements disrupt the frictionless order of state and institutional space in the global economy.

Such disruption is illustrated by a nighttime street race in Fast & Furious, in which Dom, Brian, and other drivers compete to earn a drug lord's prized job of smuggling heroin from Mexico into the U.S. Each driver's car is equipped with a GPS mapping system that transforms the crowded, downtown sector of L.A. into a hazardous, five-mile, ever-changing racecourse. The race itself, which disorders the planned flow of traffic and people, serves as a tactical re-appropriation of the municipal controlled urban grid for the drug lord's illegal contest. To navigate the course, the competitors must drive straight through intersections, dodge impending traffic, and avoid collisions (fig. 2). At one point, Brian finds himself separated from the course and must locate a circuitous route back into the race through narrow alleyways and down a steep embankment. For those of us who are repeatedly frustrated with one-way streets, traffic jams, and obstructions, this exhilarating racing sequence, which has plenty of car crashes and destruction, offers a strong and visceral sense of unbridled urban freedom and mastery.

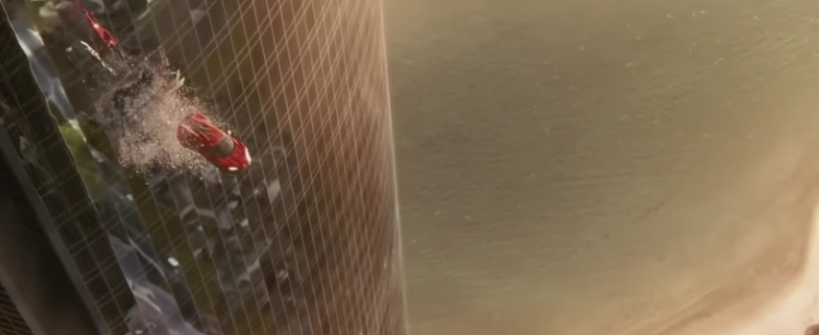

The Fast Saga likewise displays the crew's mastery over iconic architecture, such as the Etihad Towers in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as featured in Furious 7. Etihad is a collection of five high-rise buildings envisioned to be symbolic of Abu Dhabi and its global and cultural ambitions. The tallest tower is 76 stories and over 1000 feet in height, placing the towers into the category known as "super talls."17These buildings are constructed less for actual lived experience than for their signification and dissemination across the global image economy.18 The interior spaces of the towers are standardized, cellular spaces designed to block out any physical, social, and political contaminants that could compromise the enclosed environment for the building's occupants.19 In the film, Dom and his crew attend an exclusive party in one of the Etihad Towers to steal a flash drive containing a computer chip from an Arab prince hidden in a Lykan Hypersport, a $3.4 million dollar sports car.20 With security and Deckard Shaw (Jason Statham) in hot pursuit, Dom and Brian drive the Hypersport through the windows of the Towers, one tower to the next (fig. 3). Retrieving the drive, Dom and Brian dive out of the car just before it goes through the last tower window and crashes to the ground. Dom and his crew's engagement of the Etihad Towers for a heist and the ensuing destruction of the expensive sports car, fine art, and wealthy furnishings functions not to disorder the buildings' image within the global economy. Moreover, though, it also grounds the buildings' affluent skyline residents and guests in a kind of chaos and instability akin (in intensity and intrusiveness if not in its specific mode of expression) to that experienced by the working-class and impoverished people who live on the ground level of the city. Through their creative intervention, Dom's team physically transforms the Towers' intended status as a global non-place into a place of embodied experience and meaning, both for themselves and for film spectators.

As they navigate streets and buildings, Dom and his crew also contend with global technological networks — the communications infrastructure that constantly scans the world for people and information. National security and the global economy are predicated on such global networks, which are intentionally designed to rationalize and control physical space across the world. In this process, lived experience connected to local places is marginalized. Jones argues that action cinema expresses this marginalization by presenting an action hero who must contend with the perils of being tracked by a global network.21 In The Fast Saga films, Dom's team must battle a set of nefarious actors intent on acquiring and profiting from global surveillance and military technologies dominated by state entities. One of the technologies featured is the God's Eye, which can hack any technology that uses a camera and then be used to track anyone in the world.22 The God's Eye is the perfect name for an omniscient surveillance program capable of transforming local places into instrumental, homogenous abstract spaces made visible on a computer screen. In Furious 7, the team allows a terrorist to track them using the God's Eye across L.A. Dom's crew must evade the terrorist's two weapons of global warfare: a stealth helicopter and an aerial drone. Dom and Shaw fight each other on top of a public parking garage, an anonymous "non-place" with minimal relational meaning to people or a sense of history. The helicopter attacks Dom and Shaw, and the parking garage collapses to the ground. Hobbs demolishes the predatory drone with an ambulance and Dom crashes his car into the terrorist's helicopter, leaving a bag of grenades. Hobbs shoots the grenades, destroying the helicopter and killing the terrorist. Because of Dom and his crew's localized knowledge of downtown L.A. and their daring driving skills, they are able to ground the high-flying terrorist and his forces to the personal level of the city. They therefore once again contest forces that serve to abstract and homogenize space, instead insisting on its embodied, local nature and claiming considerable power therein.

Since Dom and his extended family serve multiple roles as international fugitives, government agency mercenaries, and targets for criminal global actors, they must stay continuously on the move across the world to ensure their safety. While they do make visits back to the familial Toretto house and neighborhood in L.A., they cannot really settle down. In their international movements, Dom and his crew have more in common with the globetrotting transnational capitalist class than the local people they encounter in their adventures. Although Dom's team defeats its adversaries by appropriating, controlling, and disrupting the frictionless, glossy surfaces and structures of global state and corporate spaces, the success of their sanctioned missions conversely supports the same capitalist system that built and maintains these same spaces. By protecting state surveillance and military technologies, the team sustains the global dominance of American imperialism. And yet, despite the internal contradictions at play in The Fast Saga films, they still serve for audiences as popular filmic fantasies of global mobility and wealth accumulation.

David Pierson is a professor of media studies in the Department of Communication and Media Studies at the University of Southern Maine in Portland, Maine. He has published numerous articles and chapters on Combat!, C.S.I.: Crime Scene Investigation, Mad Men, Seinfeld, The Shield, The Discovery Channel's nature programming, Turner Network Television TV westerns, and the science fiction films Moon and Source Code. He has published an edited collection on AMC Network's Breaking Bad for Lexington Books and a book on the 1960s TV series The Fugitive for Wayne State University Press.

References

- See William L. Robinson and Jeb Sprague, "The Transnational Capitalist Class," in The Oxford Handbook of Global Studies, edited by Mark Juergensmeyer, Manfred Steger, Saskia Sassen and Victor Faesse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 2018, 309-327. [⤒]

- Marcus Lu, "Is the American Dream over? Here's what the data says," World Economic Forum, September 2, 2020.[⤒]

- Dylan Matthews, "The massive new study on race and economic mobility in America, explained," Vox, March 21, 2018.[⤒]

- Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity(Malden: Polity Press, 2000), 119-120.[⤒]

- Lisa Purse, Contemporary Action Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011): 68. [⤒]

- Yvonne Tasker, Spectacular Bodies, Gender, Genre, and the Action Cinema (New York: Routledge, 1993): 127.[⤒]

- Purse, Action Cinema, 45. [⤒]

- Tim Dant, "The Driver-Car," Theory, Culture & Society21, no. 4-5 (2004): 74.[⤒]

- Dant, "The Driver-Car," 62.[⤒]

- Mary Wisniewski, "Why Americans, particularly millennials, have fallen out of love with cars," Chicago Tribune, November 12, 2018; Matthew DeBord, "Young People Are Losing Interest in Cars, But That Doesn't Mean the End of the Road for Automakers," HuffPost, August 31, 2011.[⤒]

- Sarah Redshaw, In the Company of Cars, Driving as a Social and Cultural Practice(Burlington: Ashgate, 2008), 94. On cars, youth, and masculinity more generally, see Amy L. Best, Fast Cars, Cool Rides: The Accelerating World of Youth and their Cars (New York: New York University Press, 2005) and Gary S. Cross, Machines of Youth: America's Car Obsession. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018). While there are certainly women drivers in the Fast and Furious films, they are led by the patriarchal, family-centered Dom. Likewise, as with many mainstream Hollywood films, the family dilemma running through the series is masculine and patriarchal, involving Dom's relationship with his late father and his younger brother.[⤒]

- Purse, Action Cinema, 63.[⤒]

- Nick Jones, Hollywood Action Films and Spatial Theory (New York: Routledge, 2015), 72.[⤒]

- Ulf Mellström, "Patriarchal Machines and Masculine Embodiment," Science, Technology & Human Values 27, no. 4 (2002): 475.[⤒]

- Jones, Action Films, 9-13. See further Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith (Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992) and Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988).

[⤒]

- Jones, Action Films, 34-39.[⤒]

- "Dubai Dominates This List Of The World's Tallest Apartment Buildings," Business Insider India, July 26, 2021.[⤒]

- Jones, Action Films, 31.[⤒]

- Jones, Action Films, 58.[⤒]

- Lykan manufacturer W Motors has publicized the car's use in Furious 7. "Fast & Furious 7 - Behind the scenes with the Lykan HyperSport," W Motors, YouTube, September 17, 2019.[⤒]

- Jones, Action Films, 55-56.[⤒]

- "God's Eye," The Fast and Furious Wiki, accessed June 3, 2022.[⤒]