For Speed and Creed: The Fast and Furious Franchise

A personal anecdote to start: long before I became a bureaucrat, I taught Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows (1955). At first, the students sneered and laughed at the film. But when Kay and Ned rolled in the television for their mother Cary (Jane Wyman), most of the class hissed at those horrible Scott children, treating their mother so shabbily. Something similar happened to me the first time I watched The Fast and the Furious (2001). At first I rolled my eyes but by the time the cookout scene arrived I had come around. In that scene, Brian (Paul Walker) emerges from the back door of Dom's (Vin Diesel) house carrying six beers, three in each hand. Paul Walker was no one's idea of a great actor, but that simple bit of physical business with beer bottles looks completely natural, evidence of the comfort he already feels in his new undercover persona. The perfection of that little gesture and the significance of beer carries over throughout the rest of the films. These moments reveal that both the audiences for Sirkian irony, "one which is implicated, identifies and weeps, and one which, seeing through such involvement, distances itself" can happen within the same film, to the same audience member.

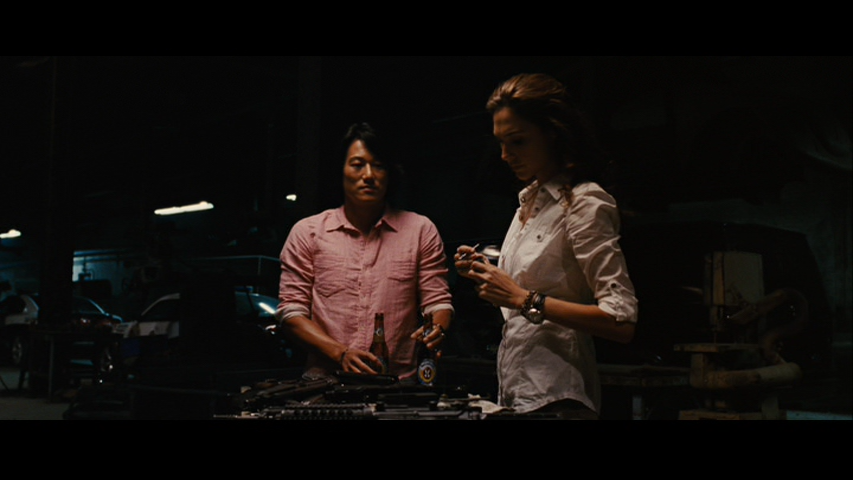

An account of the film series as a cultural diagnostic: the gearheads in The Fast Saga are hops-heads. Writing about climate catastrophe culture, Mark Bould notes that in the series, "despite all the hours of screen time spent among cars, in auto shops, on city streets and open roads, we only actually see fossil fuels three times: in the first film, a character is forced to ingest lube oil; in the fourth, gasoline briefly sprays from a fuel tanker being hijacked by Dom's crew; in the fifth, Dom douses drug money in gasoline to set it alight."1 Bould is right. Gasoline may literally fuel the cars, but beer, quite often Corona, really fuels the series and its interest in family.

Dom's Henry Ford view on beer, professed in the first movie — "you can have any brew you want as long as it's a Corona" — sounds like product placement but it isn't. Corona never paid to be featured in the films.2In any case, Corona's role in The Fast Saga is more than a kind of product placement: as an article in Vanity Fair puts it, beer is an "important member of the family."3 The frequent presence of Corona in the series thus functions as a way to understand not the industrial production of The Fast Saga, but the cultural production and meaning of The Family at the center of the films.4

An argument that takes something small and makes it something big: across The Fast Saga, beer drinking appears in an almost entirely transparent or naturalistic manner. People drink beer at cookouts, at the kitchen table talking with friends and family, and while/after working on their car. Normal beer-drinking situations. The re-imagining of family — both within The Fast Saga and in its audience — as a more capacious category emerges out of the quotidian nature of drinking beer. Moreover, placing that beer drinking both in The Fast Saga's generic historical context and in its early twenty-first century American cultural context creates a crooked continuity both with a 1950s melodrama like All That Heaven Allows and a contemporary melodrama, such as Todd Haynes's Far From Heaven (2002). The beer-drinking habits of the characters in The Fast Saga find a film history family not in the white upper-middle-class protagonists common to melodramas, but rather in good-with-their-hands outsiders like Ron Kirby and Mitch Wayne in Sirk's films, and Raymond Deagan in Haynes's. Thomas Schatz writes that "the widespread popularity and the surface-level naiveté of the melodrama usually discourage both viewer and critic from looking beyond its façade, its familiar technicolor community and predictable 'happy ending.'"5 But what if we take the surface-level naiveté literally and examine the façade (to stretch a mixed metaphor) to understand the foundation of The Family? Scenes of beer drinking show that by reorienting the melodrama around working-class-coded characters and expanding familial belonging, The Fast Saga reimagines melodrama to imagine belonging, not mobility, as the horizon to reach for.

A few by-now-standard critical concepts about melodrama: Schatz writes that, "generally speaking, 'melodrama' was applied to popular romances that depicted a virtuous individual (usually a woman) or couple (usually lovers) victimized by repressive and inequitable social circumstances, particularly those involving marriage, occupation, and the nuclear family."6 It's tempting immediately to jump into a plug-in reading that sees Dom and Brian as a virtuous and victimized couple, because they are. In the first movie in the series, Brian's cop bosses want him to put Dom in prison; Dom's Family members want him to cut Brian loose. Neither gives in to that immediate pressure. Instead, they put their reputations on the line on behalf of someone in whom they see more than what immediately meets the eye. Brian doesn't want to lock Dom up because he and the normalizing power of the Family outweigh any penny-ante smuggled DVD player bust. Dom doesn't want to cut Brian loose because even though he's a cop, he's a cop for whom the spirit of the law matters more than the letter of the law. But it's equally important to keep sight of the forms that repressive and inequitable social circumstances take: law enforcement, almost always in luxurious headquarters, doesn't care about the collateral damage its demands on Brian and Dom create, and that damage almost always occurs where marginalized people live and work. The virtuous street racers/heist experts have happy relationships/marriages across ethnic and racial differences, and they expand their nuclear families by having kids and by embracing their fellow workers to create a larger Family. In this respect The Fast Saga becomes a near-carbon copy of the mid-1950s melodramas, which Schatz argues "projected so complex and paradoxical a view of America, at once celebrating and severely questioning the basic values and attitudes of the mass audience."7 Guns, God, and Family form the foundation of the series, but the white Protestant gun-toting cop is the undisputed outsider.

A melodrama's visual style signifies powerfully. As Christine Gledhill writes, it is "the syphoning of unrepresentable material into the excessive mise en scène which makes a work melodramatic."8Gledhill analyses how sexual difference and identity are simultaneously repressed and represented in the excessive mise en scène. In The Fast Saga, much the same occurs with what constitutes a normal American family.

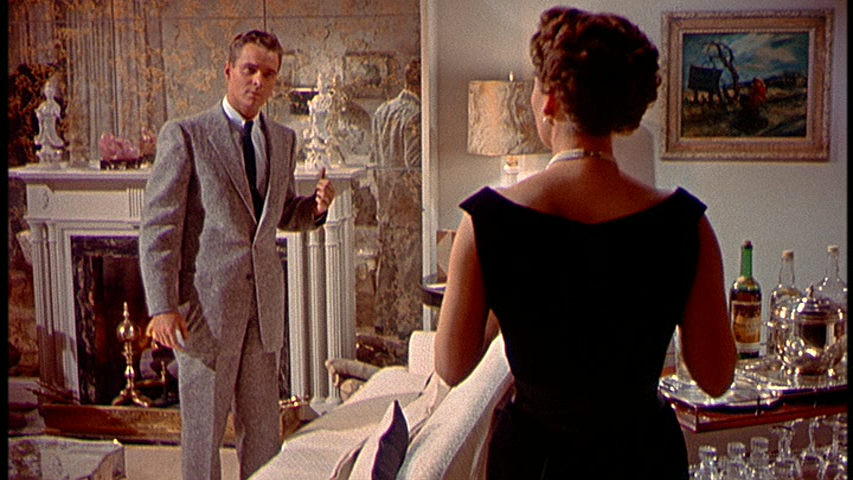

A couple of historical examples of melodrama drinking: Moments of social interaction that show class and racial divisions in All That Heaven Allows, Far From Heaven, and The Fast Saga feature liquor as a key diagnostic element of those interactions. Consider when, in All That Heaven Allows, Cary goes to visit Ron's friends Mick and Alida Anderson. In Cary's upper-middle-class world, people drink cocktails, hard liquor. But Mick, Alida, and Ron drink chianti, easily identified by its fiasco.

A cheap wine like chianti is for Thoreau-reading bohemians like Ron, Mick, and Alida and white ethnics like Manuel and Margarita, who struggle against repressive and inequitable social circumstances, not the cocktail-drinking WASPs in Cary's world. Ron is just the help in Cary's garden; Mick, Alida, and white ethnics don't have a place in Cary's neighborhood. In Far From Heaven when Cathy (Julianne Moore) has her friends over they drink from a pitcher of cocktails.

In one scene Cathy's friend Eleanor (Patricia Clarkson) makes a phone call from her very well-stocked home bar. The Scott family house doesn't have a full bar, but they have a well-provisioned cocktail cart, with multiple hard liquor options.

When Cathy joins Raymond (Dennis Haysbert) at a bar with an entirely Black clientele, Raymond has a beer, as do the people at the bar who struggle against repressive and inequitable social circumstances. Cathy doesn't; she has a daiquiri. Try though she might, Cathy can't change her thinking and actions to connect with Raymond and the Black people of Hartford who have been invisible to her for so long, even in a gesture as simple as changing her drink order to what nearly everyone else at the bar is having. In the social worlds of melodramas, people have specific drink choices that remind us of who belongs and who sits on the outside.

A series of beer-drinking scenes in The Fast Saga: sharing a drink with someone, a cold Corona for instance, creates a bond, demonstrates friendship and belonging. Dom uses Coronas to mediate his Family relationships in The Fast and the Furious. The first Corona Dom gives Brian as part of The Family is taken from Vince, feeding Vince's fear that Brian will replace him. Dom lets Brian know that the beer was taken from Vince, so he should enjoy it. This elaborate macho posturing of unmanning Vince by taking his beer reveals not just the usual association of beer-drinking and (often anxious) masculinity so familiar from advertisements but also how melodrama and bodily excess go together: "the melodramatic episode is to drama as slapstick is to comedy."9 Rising to the moment, Brian looks over at Vince and pointedly cleans the mouth of the bottle with his shirt. To accentuate the power play, a close-up of the shirt wiping the bottle is accompanied by a squeaking sound pushed to the front and then a pan up to Brian taking a drink to cement his friendship with Dom and guarantee Vince's anger. Brian's second Corona appears at the cookout where he and Vince have a passive-aggressive drink-off. Vince contemptuously pours his Corona into his mouth without putting his lips to the bottle, eyeballing Brian the whole time. After a brief shot of Dom looking from one side to the other, from Vince to Brian, Brian casually has a drink from his Corona. The shot sequence of Vince-Dom-Brian highlights the triangulation at play as the two contend to be first in Dom's heart.

Mr Nobody (Kurt Russell) tries to be first in Dom's heart via Corona too. The introduction of a microbrew-loving agent who wears a suit rhymes with the ever-more outlandish tech The Family uses. The slick, suit-wearing Mr Nobody loves a monk-recipe Belgian beer, and by contrast the no-nonsense working-class coded Dom still loves Corona. As the series escalates the stakes to include saving the whole world and going into space, the Most Popular Imported Beer in America anchors characters to normalcy and shows who continues to retain their connection to the Family.

Dom and Brian celebrate re-joining forces with a Corona in Fast & Furious, but the bad guy doesn't drink beer.10 In fact, the bad guys and antagonists across The Fast Saga — all of whom register as non-working class in their professions, residences, and habits — stay away from beer. Instead, they drink cappuccinos (The Fast and the Furious), champagne (2 Fast 2 Furious), wine (Furious 7), and hard liquor (The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, Fast & Furious, Fast Five). Here The Fast Saga runs counter to the example of melodramas like All That Heaven Allows and Far From Heaven, in which the central characters drink hard liquor, while retaining the tendency for drinks to reveal social boundaries and belonging.

In the Family barbecue in The Fast and the Furious, Coronas take up the center of the table. When Jesse says grace, a six pack of unclaimed beers sits at the center of the table. When Roman (Tyrese Gibson) says grace at the happy ending cookout in Fast & Furious 6, what looks like half a case's worth of already-finished Coronas crowd the table alongside in-progress ones.

The film-closing reunion-cookout of F9 adds some luxury to the Corona supply, showing not just six on the table, but also an ice bucket full of bottles.

Beer getting warm or staying cool aside, the excess of the piled-high nature of the table — beers and food and oversized bowls — matches the emotion in the cookout scenes. The Fast and the Furious's "syphoning of unrepresentable material into the excessive mise en scène" syphons off not the emotion inherent in the cookout scenes, nor the capacious sense of belonging, but the unrepresentable normalcy of it all. It's not just "cookout" that says Family, but the excess of Coronas that says, quite loudly, "middle of the road beer choice at this cookout." These people may drive tricked out cars like maniacs and experience death-defying chases regularly, but they're a normal family underneath.

A brief moment to consider other beers: even when Corona doesn't appear, as in Fast Five, beer remains part of the excessive mise en scène. Fast Five takes place in Brazil, and The Family's choices in beer, Brahma and Antarctica, are popular Brazilian beers from Corona's parent company AmBev. Macrobrews, in other words.

Fate of the Furious returned the series to the US, where to much speculation the AmBev macrobrews Budweiser and Stellas Artois replaced Corona.11 In every case, though, The Family eschews fancy monk-brewed beers. Corona or other macrobrews only.

Mark Bould's ecocritical account of The Fast Saga agrees with the prevailing positive reading of the films, calling them "documents of petrocultural barbarism" which "nonetheless glimpse post-white supremacist civilization."12 This glimpse of post-white supremacist doesn't reside simply in the visual/physical presence of white, Black, Asian, and Latinx Family members, important as that presence is. When the first film in the series, The Fast and the Furious,was released in 2001, Corona Extra was the top imported beer in America,13 and when The Family got back together for Fast & Furious in 2009, Corona Extra was still the top imported beer in America.14 I take no position on Corona's quality qua beer. But it's simply a fact that Corona is a very good-selling beer — the most popular imported beer in the U.S. in the twenty-first century. The Family as a multicultural version of a better America gets partway there by including a recognizably Mexican beer as part of their signature, much as multicultural America includes a significant portion of Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans. After all, the Belgian beer Stella Artois only appeared in one of the films. When they're not doing heroic things like drag racing and saving the world from hackers, the post-white supremacist Family does what millions of other people in the United States do: drink the most popular imported beer in America. The people in the world of The Fast Saga seem to see Dom and the Family as the standard toward which to strive — Brian loves and joins them; the US government needs them. The glimpse of a better world that the franchise offers builds on a familiar foundation of Coronas, guns, and Family. Like their predecessor family melodramas, The Fast Saga at once celebrates and severely questions the basic values and attitudes of the mass audience.15 The series continues to pose the question: who belongs to and who makes up the American family?

In the end, a simple point: underneath this celebration and questioning, the excessive mise en scène of so many Coronas — on the table, in a bucket, in Vin Diesel's hand — makes it easy for an audience to recognize The Family as regular-ass people who drink one of the most popular beers in America. To cheer for them is to embrace their internationalized, multiracial, multicultural, non-nuclear, and (at one point) working-class composition. The Fast Saga retains a sense of mobility — after all, billionaires like Jeff Bezos go to space, not car mechanics — but that mobility emerges from collective effort, from the Family working together to keep each other and the world safe, and being justly rewarded. The series imagines the power of togetherness and an expansive sense of who belongs to an extended family as the real benefit of mobility with every melodramatic adventure, and with every Corona-stocked Family cookout that celebrates its success.

Christian Giallombardo Long lives in Meanjin Brisbane, where he works in an office. He is the author of The Imaginary Geography of Hollywood Cinema, 1960-2000 and the editor of ReFocus: The Films of Albert Brooks and (with Jeff Menne) Film and the American Presidency. This article is because of the people of Carpentersville, Illinois.

References

- Mark Bould, The Anthropocene Unconscious: Climate Catastrophe Culture (London: Verso, 2021), 138.[⤒]

- Joanna Robinson, "Is This Why There's No Corona in Fate of the Furious?" Vanity Fair,April 13, 2017.[⤒]

- Robinson, "No Corona."[⤒]

- I'll be using "The Family" to talk about the whole Toretto orbit.[⤒]

- Thomas Schatz, "The Family Melodrama," in Imitations of Life: A Reader on Film & Television Melodrama, edited by Marcia Landy (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 152.[⤒]

- Schatz, "The Family Melodrama," 149.[⤒]

- Schatz, "The Family Melodrama," 150.[⤒]

- Christine Gledhill. "The Melodramatic Field: An Investigation," in Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Women's Film, edited by Christine Gledhill (London: BFI, 1992), 9.[⤒]

- Raymond Durgnat, "Ways of Melodrama," in Imitations of Life: A Reader on Film & Television Melodrama, edited by Marcia Landy (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 136.[⤒]

- I'm skipping over 2 Fast 2 Furious and The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift because paterfamilias Dom features in them very little.[⤒]

- Robinson, "No Corona."[⤒]

- Bould, The Anthropocene Unconscious, 136.[⤒]

- "Beer Trends 2002," Cheers, February 8, 2007. [⤒]

- Jamie Popp, "2004 Beer Report," Beverage Industry, May 1, 2004; Christian Smith, "These are the top 20 most popular beers in America, according to a new survey," The Drinks Business, April 6, 2021. [⤒]

- Schatz, "The Family Melodrama," 150.[⤒]