Abortion Now, Abortion Forever

From Deep Care: The Radical Activists Who Provided Abortions, Defied the Law, and Fought to Keep Clinics Open

Forthcoming AK Press, November 2023

I didn't set out to write a book about the gynecological and abortion "self-help" movement and about clinic defense. Deeply interested in the work of feminist and queer American poets who were also health activists — Audre Lorde, Judy Grahn, Pat Parker, and more — I was researching an academic book about poets and poetry. It was (and still is) compelling to me that these poets wrote about how their social and material environments had made them sick and how they imagined feminist medicine and healing as forms of empowerment and resistance.

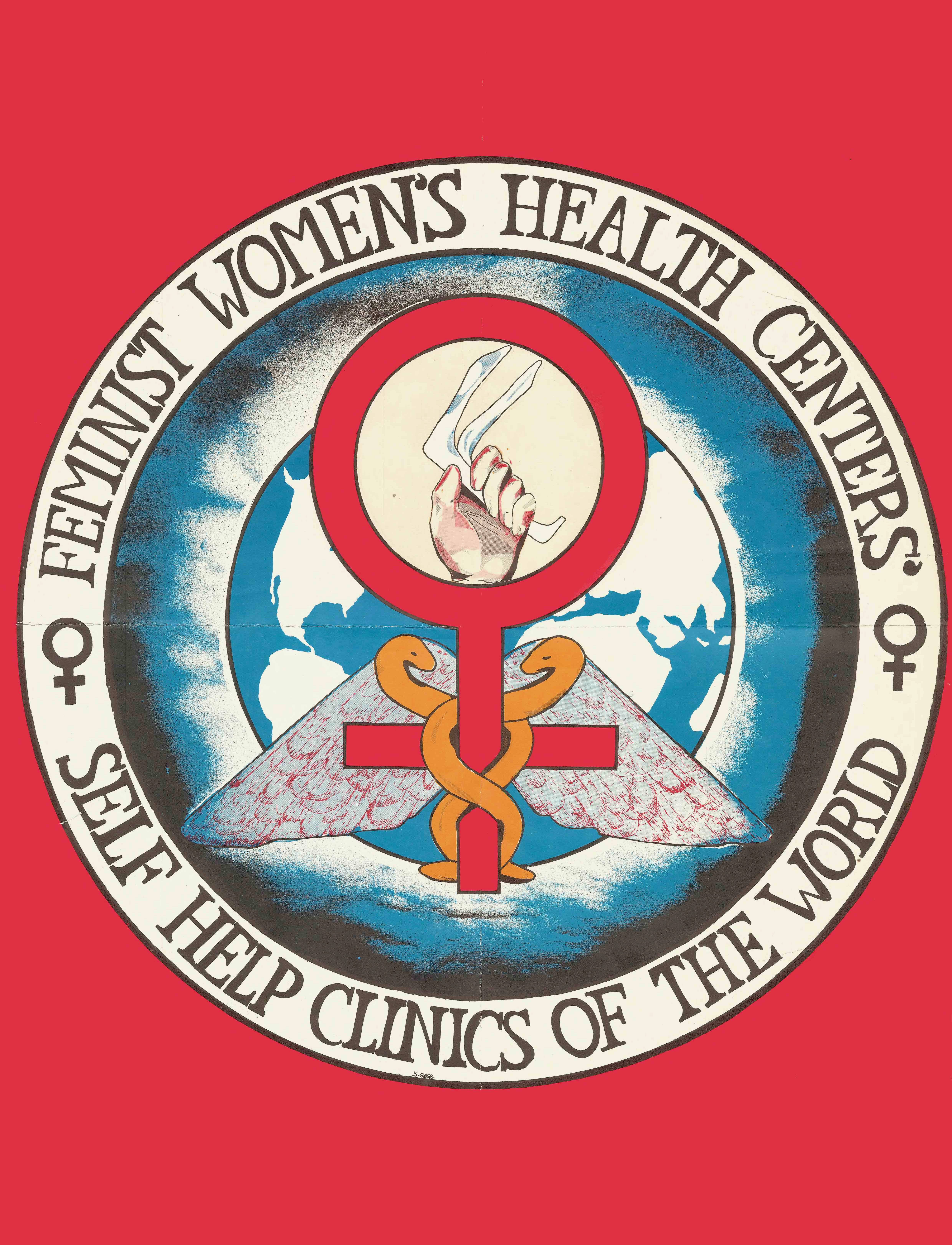

This was how I learned that Pat Parker, a Black lesbian feminist revolutionary and poet, had worked at the Oakland Feminist Women's Health Center, also known as Women's Choice Clinic (which I'll refer to as OFWHC/Women's Choice). So I started researching the clinic. I learned that it was part of a network of feminist women's health centers and abortion clinics that grew out of a West Coast-led gynecological "self-help" movement. Thus began my journey into the self-help archives.

***

I first talked to Linci Comy, the clinic's director for more than thirty years, in the summer of 2018. I'd wanted to ask her about Pat, whom she had worked with in the 1970s and 1980s. When I first met Linci, she had her blue eyebrows on. An elfin dyke witch with glittery eye makeup and hard turquoise eyes, she wore her silver hair short, punky, and queer. Among the tattoos on her arms was a rainbow-striped caduceus. She invited me inside her house and sat with me at the sunny kitchen table. My first question must have been something like, "Can you tell me about the clinic where you worked with Pat?" I couldn't have known that it was the first of what would be thousands of questions that I would ask her.

Linci grew up in a poor white Catholic family in the Rust Belt city of Lorain, Ohio. Prior to coming to OFWHC/Women's Choice, she was a Navy corpsmember who served as a medic in the Micronesian Islands, treating wounded Vietnamese refugees. Many were survivors of American chemical warfare. "When I went into the service, I thought I was going to do a good thing and be a medical person," she told me at one point. But her experience was disillusioning. "I mean, we dumped white phosphorous from the sky," she said. "We did that." When she got back, Linci wanted to find sanity. "For me, coming to the clinic after the war was about coming to a space about health."

Through our conversations, Linci helped me see that what activated and sustained the Bay Area radical abortion defense movement was the collaboration of three core components: feminist clinical practice, an abortion underground, and militant clinic defense. Abortion "self-help" — gynecological and abortion care provided in both clinic and non-clinic settings — took place in private spaces, such as exam rooms, living rooms, and bedrooms, while clinic defense played out in the public spaces of sidewalks and streets.

The gynecological and abortion self-help movement, which started in the early 1970s, is said to have grown out of Civil Rights and New Left organizing and to have been catalyzed by women's movement calls for feminists to "seize the means of reproduction."1 Historian Michelle Murphy argues that the conditions for this call were technologies that made it possible for people to "manipulate their very embodied relationship to sexed living-being," namely birth control and new abortion techniques.2

The conditions for this call also included the innovation of feminist consciousness raising. Starting in the late 1960s, the consciousness-raising movement upheld small-group work as fundamental to liberation processes. Through "opening up, sharing, analyzing, and abstracting," group members created autonomous zones where learning from lived experiences empowered them to transcend the isolation that was patriarchy's primary tool for subjugating them.3

As they applied the tools of feminist consciousness raising, self-helpers taught each other about gynecological health, anatomy, and fertility tracking. They also taught each other how to empty the uterus and end an early pregnancy with a suction technology they developed called "menstrual extraction." Through these practices, they collectively produced body knowledge and helped others achieve reproductive autonomy.

Across the decades, abortion self-help has been a multiracial, cross-class movement. As first-generation self-helpers noted to me, in the early 1970s, the movement was made up of mostly working-class white women. But due to its grounding in the birthplace of the Black Panther Party, Bay Area abortion self-help internalized and reflected Black radical ideas from the beginning. In the 1980s, women of color, including Pat, were the leadership of OFWHC/Women's Choice.

***

In the fall of 1977, Pat Parker arrived at the health center. She was thirty-three at the time and a well-known lesbian poet. Pat was good friends with the poet Judy Grahn and, through Judy, had met Laura Brown, a director of OFWHC/Women's Choice.4

Another clinic director named Alicia Jones recalled how she helped Pat get her bearings. "I was her big sister," she told me. "Even though she was older than me, she would come to me and say, 'Okay, Big Sis.' After that she would call me Jones." Alicia and Pat (or Jones and Parker) became close friends.

I wish I could have had the chance to sit down with Pat and ask her questions about her work at the health center. Had it not been for her, I never would have come to the story of Women's Choice. Like a lot of Black women of her generation, Pat developed breast cancer. She died in June 1989. While I don't have access to whatever oral history she would have provided, I — we — do have access to her poems. And it was through her poems that Pat told the truth about the world around her.

Pat grew up poor and working class in the Houston area. When she was in her late teens, she moved to California. In her first decade in the Bay Area, Pat was radicalized by the Black Power movement and became a Black Panther. She also became a poet: in 1971, she published her first book, Child of Myself, with Shameless Hussy Press. Judy and Wendy Cadden's Women Press Collective (which would later merge with Diana Press) reprinted the book in 1972.

When she joined the health center in 1977, at the encouragement of Laura, Pat had never done health work before, but she was eager to learn. Her own experiences of structural violence against Black girls and women had prepared her. As a child, she survived rape, and as a teenager, she became pregnant and gave birth (she chose adoption for her baby).5

In September 1979, Pat wrote in her journal, "Am becoming quite the gyn worker. Still a tremendous amt. to learn, but I'm getting good at it."6 At the health center, she promoted a Black radical politics but rejected the masculinism she saw in the Black Power movement.7 Her handwritten bio for a Diana Press author questionnaire states that Pat Parker "was a member of the Black Panther Party for a short time but found the sexist attitude of the men intolerable. Women did the office work and were, for the most part not involved in policy decisions." She also noted that, after coming out in 1968, her "attitude toward her work changed."8Pat refocused her energy on doing antiracism education within the women's movement. She often confronted racism through her poetry: "SISTER! your foot's smaller, / but it's still on my neck."9

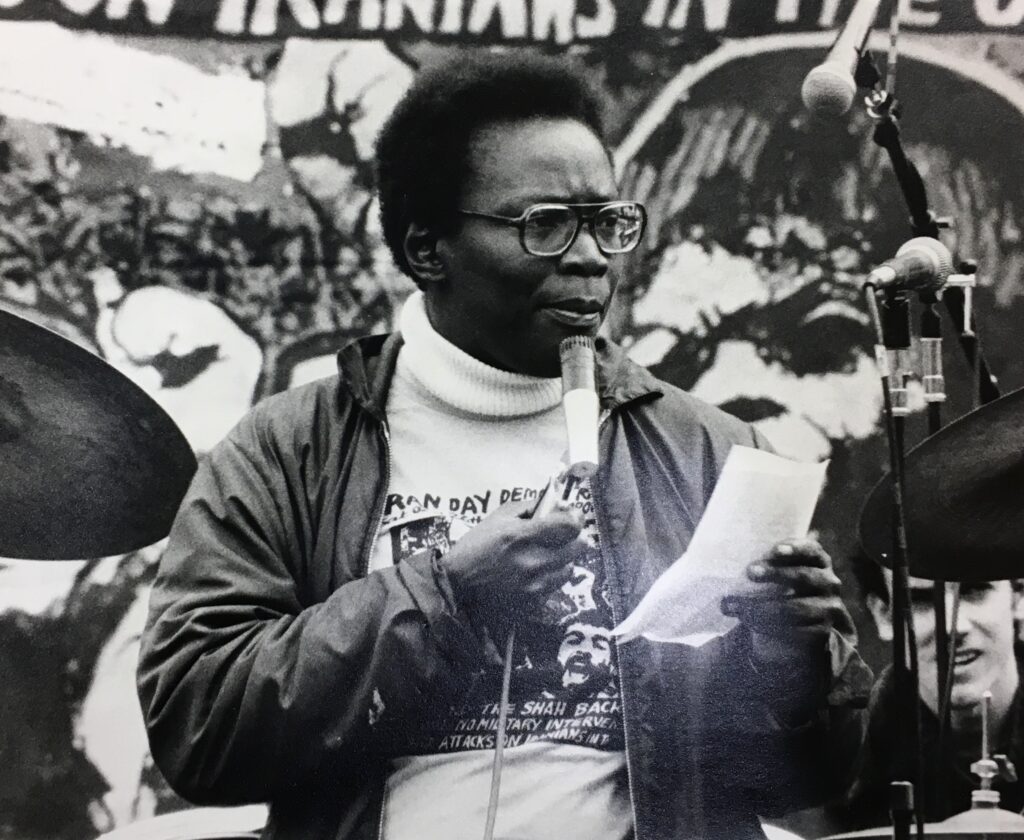

In a speech called "Revolution: It's Not Neat or Pretty or Quick," which she delivered at the 1980 BASTA Women's Conference on Imperialism and Third World War in Oakland, Pat elaborated her Black radical feminist commitment. She spoke on behalf of the Black Women's Revolutionary Council, the Eleventh Hour Battalion, and OFWHC/Women's Choice. She argued, "[An] illusion that we suffer under in this country is that a single facet of the population can make revolution. Black people alone cannot make a revolution in this country. Native American people alone cannot make revolution in this country. Chicanos alone cannot make revolution in this country. Asians alone cannot make revolution in this country. Women alone cannot make revolution in this country. Gay people alone cannot make revolution in this country. And anyone who tries it will not be successful."10 Pat's revolutionary theory advocates a coalitional approach. Her words reflect the politics of the Combahee River Collective, which argued, in 1977, that separatism is "not a viable political analysis or strategy."11

Pat was involved at every level of clinic work and eventually assumed a director role. As the internal medical director, she was responsible for everything from writing clinic protocols to ordering supplies. In a health center audio memo dated August 7, 1985, she analyzed a series of proposals to reduce medical supply expenses. At first, the memo was indecipherable to me as a layperson. I'd heard recordings of Pat reading her poetry before, but the memo was a different thing entirely. She sounded . . . like an ordinary person: "August 7, 1985 . . . I think the idea of sterilizing [gauze] 4x4s in the sets is a good one . . . As to putting chux [pads] under women for abortions, this wasn't very clear to me: Did you mean, using chux [pads] in lieu of sterile barrier towels during abortion procedures? If this is the intent, I would not advise it."12

Confused, I ran the memo by Linci. She explained that Pat was considering the question of how best to set up kits for abortions. Each procedure needed sterile gauze: "If you wrap the gauze in your sterile pack and sterilize it with the instruments, then it just comes in the pack. And it's cheaper to buy a giant thing of non-sterile gauze [and sterilize squares along with the rest of the equipment]," she explained. "The chux is just a barrier cloth. So if you only use a chux, it means that you have a non-sterile field. It's not a good plan."

Whether she was asking the question of how to abolish capitalism as a feminist poet revolutionary or thinking through how to assemble abortion kits both economically and safely as a health worker, Pat held the minutiae together with the whole, understanding praxis through theory, and theory through praxis. If there were ever a definition of self-help, I thought, that would be it.

Pat left us with so many kernels of insight. Here's one from her 1980 speech on the relationship between reproductive freedom and power in the social realm: "The nuclear family is the basic unit of capitalism and in order for us to move to revolution it has to be destroyed . . . The male left has duped too many women with cries of genocide into believing it is revolutionary to be bound to babies. As to the question of abortion . . . The question is whether or not we have control of our bodies which in turn means control of our community and its growth."13 Pat suggests that Black Nationalism's heterocentric pronatalism is misguided because all ideologies of the nuclear family are ideologies of capitalism, in that they reinscribe the idea that the primary role of women in society is to have children and reproduce labor power. She argues that for women to be free from this capitalist exploitation and, moreover, have power in their communities, they must have access to reproductive autonomy; therefore, abortion access is integral to the freedom of women. And until Black women are free (that is to say, until Black women have real access to abortion), no one can be free.14

"I've always tried to follow in the footsteps of Pat," Linci once told me. "She taught me to speak. And to trust rhythm. Fuck everybody. Say it how you wanna say it. Say it loud. Don't say anything you aren't willing to eat."

Pat died of breast cancer on June 17, 1989, two weeks before the Supreme Court's ruling on Webster v. Reproductive Health Services — the decision that would pave the way for the gutting of legal abortion access. In the last interview she ever gave, which she did on the topic of abortion that March, Pat told the Bay Guardian, "One of the things that's real clear is that if abortion is lost, women of color are going to die . . . Roe v. Wade is in deep trouble, and people need to understand that."15

***

In addition to being a feminist clinic, OFWHC/Women's Choice was a place where health workers could share the labor of parenting. Of Black women's parenting experiences, Pat wrote in her poem "Movement in Black":

I'm the woman who

Raised white babies &

Taught my kids to

Raise themselves.16

Pat points toward how, historically, Black women have been alienated from parenting roles by capitalism. First, by chattel slavery, and later, by an economy that continued to exploit Black women's (reproductive) labor power.

As social theorist Patricia Hill Collins points out, American gender and family ideologies grow out of the market-imposed binary between "public" paid labor and "private" unpaid housework.17 And the devaluation of the latter is a product of modern capitalism, as activist and scholar Angela Davis, among others, argues.18 Because Black women's work has straddled the public-private binary since slavery — because they have long "carried the double burden of wage labor and housework"19 — Black women's labor and intimate relationships have been, as Collins phrases it, "deemed deficient."20

As opposed to allowing capitalism to define and oppress them through their waged work, the women of OFWHC/Women's Choice tried to define their work for themselves. At the clinic, both women of color and white women resisted the racist economic imperative for women of color to leave their children behind while they worked outside of the home. As Alicia, Linci, and the other clinic workers I interviewed explained to me, all the women brought children to work and supported each other as parents both at and outside of the clinic.

Alicia had a son, whom she'd brought with her when she moved from Chicago to California. She recalled how her friends supported her as a single parent and how her son connected with Pat. "She was an auntie to him," Alicia said. If she had to work a Friday night clinic, she knew she could ask Pat to take her son to his baseball game. "She was there for him," Alicia said. "And he appreciated that."

In a poem titled "maybe i should have been a teacher," Pat writes about the seemingly impossible task of negotiating a writing career with a job, housework, and caregiving responsibilities. The poem begins, "The next person who asks / 'Have you written anything new?' / just might get hit." She also wrote of finally getting a vacation from the health center only to have to deal with a sick dog and a sick kid.

call Alicia

'What do you do

for fever?'

aspirins, liquids,

no drafts.21

When I asked her about the poem, Alicia told me the story behind it:

[Pat's daughter] had a fever. She had given her baby aspirin and didn't know what else to do. So I said, "Warm up the bathroom. Fill the tub with tepid water. Warm enough that when you put your wrist in, it's not cold but not hot. Get some alcohol. Sit her in that tub, and make sure the bathroom is warm, because you're going to open up all of her pores. Soak the towel over her with the alcohol and hold her up. Don't let her lay back or go to sleep. Rub her body down with the alcohol cloth and water. Put a towel in the dryer and have it nice and warm. When you take her out, get her all dry in the bathroom where it's still warm, and get her bed ready, and then put her in her pajamas and tuck her in real good. And that fever's going to break. Make sure you have extra pajamas for her because with the heat flashes the bed will be totally wet."

I called her first thing the next morning, and Pat goes, "Girl, you were right. That fever broke. She was wet like she was in the tub."

In February 1986, Pat gave a reading with Audre Lorde at the Women's Building in San Francisco. The first poem she read was "maybe i should have been a teacher." She prefaced it by saying that there were a couple references that she should "clear up": "There's an area of the poem where I talk about a woman being pregnant in her stomach. And after reading this poem several times, I found out that many of us still believe that women get pregnant in their stomachs, from the days when our mothers said, 'There's a baby in my tummy.' We don't get pregnant in our stomachs if we can help it." The audience laughed, and then Pat added, in all seriousness, "That's why we have uteri."22 In the poem, she refers to a case that she saw at the health center of an extrauterine pregnancy, when the embryo or fetus grows outside of the uterus and attaches to a fallopian tube or, in some rare cases, bowel or other organ.

At work

start on

the new protocols

go to director's meeting

write a speech for a rally

on the weekend

lab work returns

no products of conception

call the woman

get a sonogram

she's pregnant—but

in her stomach.23

Pat gets at the way clinic work was always more than just a job — it was activist work. It meant being available to respond to emergency situations like an ectopic pregnancy, even on the weekend. It also meant showing up as a feminist health educator in many different contexts, including at a poetry reading. You could say, to use Collins's formulation, that Pat was "constrained but empowered" by her job.24

Pat's poem registers a contradiction of "feminist health work": While all work under racial capitalism is exploitative, of racialized workers especially, making it the antithesis of "health," feminist health work was also figured by feminists as critical to women's survival and liberation. The self-help clinic was a place where people literally seized the mode or means of reproduction.25

In another poem titled "love isn't," first drafted in 1982, Pat writes,26

I wish I could be

the lover you want

come joyful

bear brightness

like summer sun

Instead

I come cloudy

bring pregnant women

with no money

bring angry comrades

with no shelter

Pat contrasts the unattainable ideal of a bright and sunny, highly available lover with what she can offer as someone always busy with her activist work. Then, at the end of the poem, she writes,

All I can give

is my love.

I care for you

I care for our world

if I stop

caring about one

it would be only

a matter of time

before I stop

loving

the other.27

Here again, Pat writes of being "constrained but empowered" by her work. For her, the caring labor of intimate relationships — with lovers, friends, children — is inseparable from community care labor and liberation struggles.

Just as OFWHC/Women's Choice health workers brought family into work and activist spaces, they treated community spaces as family spaces. As Pat said: "The nuclear family is the basic unit of capitalism and in order for us to move to revolution it has to be destroyed." The practice of intimacy is never not political. And political work is never not personal.

Angela Hume is a feminist historian, literary critic, and poet. She does research at the intersections of working-class and multiethnic American literatures, feminist and queer theory, and the history of medicine. Her forthcoming historical book is titled Deep Care: The Radical Activists Who Provided Abortions, Defied the Law, and Fought to Keep Clinics Open (AK Press, 2023), and she is co-editor of the book Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field (U of Iowa P, 2018). Her poetry books include Interventions for Women (Omnidawn, 2021) and Middle Time (Omnidawn, 2016). Angela earned a PhD in English from University of California, Davis, and in 2022, she joined the faculty of College Writing Programs at University of California, Berkeley. More at linktr.ee/angelahume.

References

- See Jennifer Nelson, More Than Medicine: A History of the Women's Health Movement (New York: New York University Press, 2015); and Shulamith Firestone, quoted in Michelle Murphy, Seizing the Means of Reproduction: Entanglements of Feminism, Health, and Technoscience (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 5.[⤒]

- Murphy, Seizing the Means, 5.[⤒]

- Pamela Allen, "The Small Group Process," in Free Space: A Perspective on the Small Group in Women's Liberation (New York: Times Change Press, 1970), 23-31.[⤒]

- Judy Grahn, A Simple Revolution (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 251-52.[⤒]

- Grahn, Simple Revolution, 185; Pat Parker, "For Donna," in The Complete Works of Pat Parker, ed. Julie Enszer (Dover: Sinister Wisdom, 2016), 40-41.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, journal entry, MC 861, box 8, folder 11, Papers of Pat Parker (hereafter PPP), Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute, Cambridge, MA (hereafter Schlesinger).[⤒]

- For more on Black women's critiques of Black Power, see Benita Roth, Separate Roads to Feminism: Black, Chicana, and White Feminist Movements in America's Second Wave (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 82-85.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "Author's Questionnaire [Pit Stop]," MC 861, box 11, folder 16, PPP, Schlesinger.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "Have you ever tried to hide," in Complete Works, 55.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "Revolution: It's Not Neat or Pretty or Quick," in This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, Fourth Edition, ed. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (Albany: SUNY Press, [1981] 2015), 241.[⤒]

- Combahee River Collective, "A Black Feminist Statement," in This Bridge Called My Back, 210-18. Also see Barbara Smith, Introduction to Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, ed. Barbara Smith (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, [1983] 2000), xl; Bernice Johnson Reagon, "Coalition Politics: Turning the Century," in Home Girls, 343-55; Collins, Black Feminist Thought, 42; and also Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor's interview with Barbara Smith in How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, ed. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 29-69.[⤒]

- Health center memo, 1985, audiocassette, T-523, PPP, Schlesinger.[⤒]

- Parker, "Revolution," 242.[⤒]

- This was the argument of the Combahee River Collective, too: "If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression." See "A Black Feminist Statement," 215.[⤒]

- Laura Fraser, "Abortion Rights: A Time for Fear," San Francisco Bay Guardian, March 29, 1989, Newspaper Archive, Oakland Public Library.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "Movement in Black," in Complete Works, 99.[⤒]

- Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, Second Edition (New York: Routledge, [1990] 2000), 47.[⤒]

- See Angela Davis, "The Approaching Obsolescence of Housework: A Working-Class Perspective," in Women, Race & Class (New York: Vintage Books, [1981] 1983), 222-244.[⤒]

- Davis, Women, Race & Class, 231.[⤒]

- Collins, Black Feminist Thought, 47.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "maybe i should have been a teacher," in Complete Works, 211-212.[⤒]

- "Audre Lorde, Pat Parker 2/7/86 Reading," recorded 1986, San Francisco Poetry Center and American Poetry Archives, San Francisco Public Library, video cassette; and also Poetry Center Digital Archive, https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/poetrycenter/bundles/238556.[⤒]

- Parker, "maybe i should have been a teacher," 213.[⤒]

- Collins, Black Feminist Thought, 46.[⤒]

- "Mode of reproduction" is Martha Gimenez's phrase. See Martha Gimenez, Marx, Women, and Capitalist Social Reproduction (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2019). "Means of reproduction" is Shulamith Firestone's, quoted in Murphy, Seizing the Means, 5.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "'Poem: I wish I could be the lover you want,' 1982," MC 861, box 9, folder 44, PPP, Schlesinger.[⤒]

- Pat Parker, "love isn't," in Complete Works, 190-91.[⤒]