Heteropessimism

Last summer people on Twitter were angrily discussing an Instagram account that was new to me, run by an artist, Mary Catherine Starr, who posts as @momlife_comics. Presented as sincerely autobiographical, the content is white middle-class characters and attendant text, rendered in soothing pastel colors and rounded shapes. They are arranged in vignettes that illustrate the unequal distribution of work within a conventional family home, where the mother figure does the lion's share of everything while also managing her feckless spouse. They document the emotional impact of "how women and men are seen differently," as one piece describes, impugning the patriarchal binaries that cast women in some roles and men in others. A familiar example would be how, when the mother looks after their children, it is perceived as simply natural and normal; yet when her husband is seen alone with the kids, he is hailed as a uniquely great dad and self-sacrificing hero.

At times Starr's work also laments the way the husband figure will "weaponize incompetence" — a phrase that has caught on across feminist social media lately, basically describing how doing things badly ends up, wittingly or not, being a way of getting out of being asked to do anything to begin with. This very structure of relation — women are the ones who ask men to do things — also comes into focus in this work, as Starr registers the common feeling that she is responsible for much of the burden of organizing the household, with the rest of the family just along for the ride. Starr uses the language of "unpaid work," too, to grasp some of this inequity, to fault the way that the activities she does to take care of the family are considered natural to her as a mother — and in this way, not work at all.

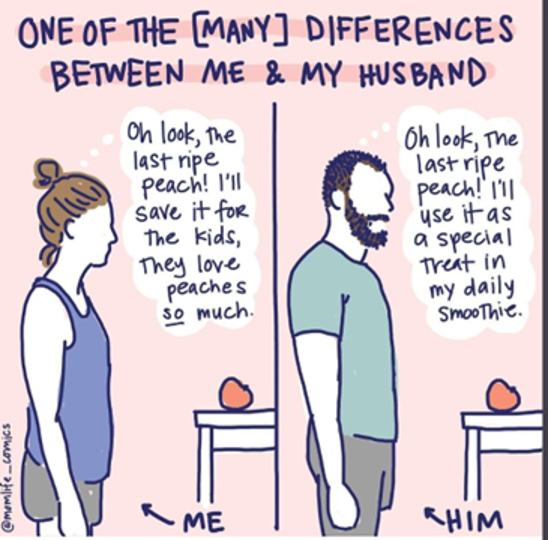

One image seemed to provoke commentators particularly, prompting the sudden online storm I had been noticing, and then eventually the artist's defensive response. Here (fig. 1), Starr compares the mother's thoughts on a single remaining peach with the husband's rather different perspective. Cherishing their pleasure above her own, the mother thinks she will save it for the kids. Caring more about his own desires, the father prefers to use it himself. Observers lamented that the artist was building a social media following by mocking a man who just wanted some simple pleasure after working hard for his family; or they stated that she should probably get a divorce if her partner is so noxious to her; or they said she was a "wine mom" who ultimately can't stand her family, or even an ungrateful, "unemployed" stay-at-home wife parasitically dependent on the same spouse she was dragging online.

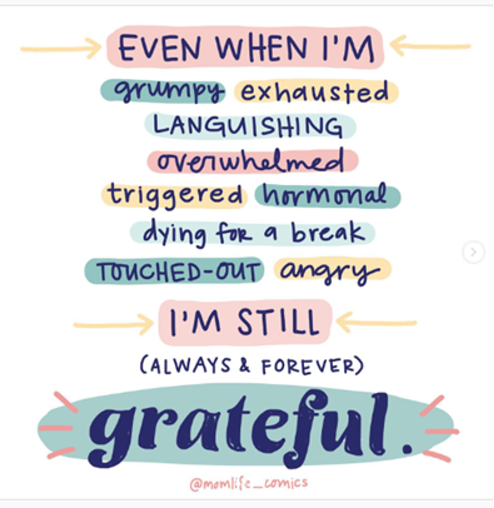

In the face of so much hostility, Starr felt compelled to reassure everyone that, despite seeing room for growth, she does love the man depicted in the comics. In a later post (fig. 2), she used the words "always & forever grateful" to describe her disposition toward her family life.

She defended the activity of complaint as well: it helps to build a sustaining community in which people can bond over common experiences, and ultimately helps to strengthen the couple, by offering the husband counsel in the realities of patriarchy and in how to look inward and be better. And after all, she indicated in her response to the backlash, isn't questioning a woman's right to express herself in this way itself patriarchal?

***

There is much here that is exemplary of that "mode of feeling" and "performative disaffiliation" from heterosexuality that Asa Seresin has described as characteristic of popular forms of heteropessimism.1 I want to draw upon Seresin's critique of these forms to point to something a bit outside of his foundational treatment — a specifically "domestic heteropessimism" illustrated in Starr's work, fixated on the family home and the unequal distribution of housework and childcare that takes place there. Even if, as we know, the comics are designed ultimately to elicit online engagement, grow a monetizable following, and sell products with pictures of peaches on them, they are only effective grounds for this kind of use because they tap importantly into something that is common to the gendered experience of contemporary family life.

Specifically, they highlight the unequal distribution of tasks within the heterosexual couple-based household, while largely leaving to one side the question of how individual attachments within families, along with gender itself, are historically conditioned by shifting domestic arrangements that mediate regimes of work and consumption as they emerge. As Seresin argues, the dominant affective dispositions and cultural forms of heteropessimism "always seems to operate on the level of the individual," thus "metabolizing the problem of heterosexuality as a personal issue" to be solved within the couple itself.

In Starr's domestic heteropessimism, this individualization follows a particular pattern. In defense of her comics, she explains that, despite the patriarchal organization of work within the home, she is grateful to her family and loves her husband. The inverse might be just as true: as many feminist histories of family life have indicated, the idealization of familial love has accompanied women's sequestration within the family home and ongoing overburdening with housework even in dual-income households. (They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.)In Starr's comics, gratitude and attachment are presented as the ultimate antidotes to her bad feelings about what work within the home requires of her, rather than as themselves produced at a deeper level by the compulsion to form into couple-based households to begin with. Familial love, in other words, is figured as the answer to domestic heteropessimism, and not as a feeling attending the very perpetuation of isolating, dependent, harrying conditions in which heterosexual misery is so common.

The closest thing to a structural critique in this work, reaching beyond treatment of unhappiness as a personal issue, is in Starr's approach to "The Patriarchy." Here, the individual "men in our lives aren't necessarily the issue." Instead, there is a "bigger force" that "has been teaching ALL of us" (fig. 3). We notice though that this critique is still ultimately pitched at the level of individual consciousness, to be resolved in the personal realm. In Starr's treatment, patriarchy arises from bad discourse ("lies"), and conscious awareness of the problem will instigate the only real correction that is needed. This correction will then produce what is ultimately desired here, which will itself help women reconcile with their wanting to be with men to begin with: equal partnerships.

Starr's comics represent just one popular form of domestic heteropessimism, and it would be foolish to generalize too strenuously on the basis of a single popular social media account. What I think can be observed with some confidence, however, is this: some number of the performative disaffiliations that characterize domestic heteropessimism, which critique patriarchal norms shaping the household, fail to look beyond the couple-based household of "equal partners" toward any fuller social reorganization, just as they ignore the material determinants of patriarchy and couple-based romantic and domestic forms. In this light, domestic heteropessimism is perhaps one of the contemporary cultural forms that, in trying conditions, help reconcile people to the idea that the relationships and family situations that they are in simply cannot be reordered in any deeper way. This is the heterofatalism, as Seresin calls it, underlying everything else, combined often enough with what Hannah Wang elsewhere in this cluster terms "anesthetic feminism," a shielding of oneself from seemingly inescapable "quotidian indignities of misogyny."2 Heterofatalism would have us accept that teaching men how to live up to your heterosexual desire for them is enough, the only real goal, itself sufficiently utopian, because scarcely imaginable. Meanwhile, the destructive force of the industrious, resource intensive, isolating, often lonely, exhausting, harrying, single-family household — the very institution through which heterosexual misery is perpetuated — remains obscured.

Of course, the couple-based heterosexual household, built upon a gendered division of tasks, not least via the naturalization of particularly intensive mothering, may very well be improved by teaching men to be more attentive partners and more active participants in the organization of the home. But equality in orchestrating what is an increasingly untenable way of living hardly seems sufficient, as it will leave in place a serious constraint on any kind of contended coupledom, heterosexual or otherwise: the simple reality of being overburdened with work and worry about financial security and children's unfolding lives in isolated homes that are incompatible with planetary futurity.

Sarah Jaffe recently reminded us of how "the material relations that upheld and coerced binary gender" are collapsing, along with some of the strictures of monogamy and the traditional nuclear family.3 People are compelled nevertheless into cohabitation, by the cost of living, stagnant wages, and the difficulties of organizing and affording childcare, all especially hard for the "job-hopping" worker with no access to a predictable income. Is it any surprise that couples struggle in these increasingly prevalent conditions? Heteropessimism is a morbid symptom of a dying social order — "the end of straight history," Sean Lambert calls it elsewhere in this cluster, opening onto what is, for some, a terrifyingly vistaless future.

***

My understanding of domestic heteropessimism in Starr's work was shaped by the book I was reading around the time of the furore over the peach comic: M.E. O'Brien and Eman Abdelhadi's Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune 2052-2072. They made a fascinating pairing, as I wondered if this book's image of possible futures, of ways of organizing our relations against the model of the private household, promised real rupture. Would it remedy what beset and stifled those expressing their heteropessimism, against "that blackmail that forces people into these choked pockets," to adapt something Sophie Lewis had recently said?

Lewis was speaking to a seminar on "the family problem" hosted by the Psychosocial Foundation, a group devoted to putting the study of psychology to revolutionary transformative use. We were discussing To Abolish the Family, Lewis's latest book, which, title aside, is not about getting rid of every kind of family life, leaving people isolated monads. Lewis draws instead from past and present alternatives to the private family household, to promote a future of collectivizing care and proliferating connections toward an abundance replacing scarcity. "It's existentially petrifying to imagine relinquishing the organized poverty we have in favor of an abundance we have never known and have yet to organize," Lewis concedes.4 We wondered, as a seminar, to what extent such social transformation is ever separable from the wholesale foundation of a post-capitalist world. As Lewis's work itself often asks, in the absence of more fundamental social upheaval and remaking, wouldn't any new family form, any "experiments in living," as Kathi Weeks wrote, simply continue to mediate the requirements of the capitalist organization of work and life?5

Everything for Everyone imagines such a shift as part-and-parcel of a wholesale communization. The book describes its new world in the form of a speculative ethnography: O'Brien and Abdelhadi fictionalize their own future interviews with a range of people involved in making and sustaining the new social fabric, thus linking personal experience to transformative revolutionary activity. The communes reorder primary production of what people need to survive, from food and housing to companionship and healthcare. From there, everything else follows. With the severing of the link between human subjectivity and the capitalist labor process, non-normative variations that were already unfolding are concentrated and intensified, given space to bloom, resulting in an abundant plasticity and unlimited experimentalism in bodies, genders, families, communities.

It all emerges from a confluence of events entirely familiar from our present vantage: government capacity to manage unfolding catastrophes is dwindling; the labor market has decreasing need for full-time workers, spreading un- and underemployment and disaffected surplus humanity with little reason not to fight. Add massively expensive cleanups following dramatic climate events like forest fires and floods, threats to food chains, refugee crises, health pandemics, and a fascist resurgence that responds to the tumult by attacking any state forces that are not reasserting the power of the nation and the traditional nuclear family. In Everything for Everyone, these myriad dynamics of our present simply heighten to the point of conflagration and collapse, and, with many fronts still active sites of struggle, keeping beleaguered state forces busy, people take it upon themselves to do the now necessary work of building the new world that will sustain them.

There remain counterrevolutionary groups involved in the production of their own fascist enclaves, but the communizing communities present a real alternative. It is hard for anyone to resist the safety of having their basic material needs met, relieved of the burden of fear of hunger and of being alone and unhoused. People are compelled in this way to join in the abundant work of production and distribution of what must exist to serve those who show up. As Miss Kelly, one of the original insurrectionists, puts it: "we communized the shit out of this place." "It means we took something that was property and made it life," she continues, and she is proud that they remained open to anyone who "came to us without property or power."6 More and more people arrive in this way, as they come to see that it benefits everyone to decide together what is feasible to make and do. They are also able to devote their time to what is necessary and what appeals to their abilities, and they have opportunities to vary their work. In turn they feel like a part of something, like their lives weren't wasted in work they never really wanted to do, for ends they didn't support. They are sustained by activity that is effortful, but also deeply rewarding and defined by an exalted alterability.

There are still families! But people have much more opportunity to share the work of caring for children, so children are not weighed down by the feeling of being burdensome. Being a parent is an opening; the child is less their own and more a being in relation to many others. Children can proliferate connections and discover what they find sustaining. We are all familiar with that blessed mantra of teenage disaffection, "I didn't ask to be born!" Here, with many variations in how care work is organized, no one is asked to be the reason why their parents need to work so hard, or stay in their unhappy marriage, or never develop any other sustaining passions because they thought that their children were supposed to be enough. Children can leave the care of their immediate family and try out entering other arrangements when they wish, and never have to feel as though their material needs won't be met if they exit a household. People can always eat in common (they can also eat in private when they want to), and there are choices of places to sleep.

The private couple-based household is now, to be sure, a queer phenomenon as much as a heterosexual one: as a critique of it, Everything for Everyone offers a far more unsettling challenge to the form of the couple, straight or otherwise, than we find in the characteristic cultural forms of domestic heteropessimism. Far from imagining the possibilities for human connection and intimacy that might unfold in totally new conditions, domestic heteropessimism seems designed to help people want what there is, it would seem, no choice but to have: a heterosexual partner and children in a family home. It evinces a form of longing for equitable couple-based interpersonal relationships that eschews the promise and necessity of communizing care via overcoming capitalist social relations. In Everything for Everyone, by marked contrast, overcoming capitalism is the only unsettling that would truly transform every kind of coupling, by shifting its orienting settings and priorities away from closed domestic units that intensively consume products while generating and organizing private wealth.

One effect of the future setting of Everything for Everyone is that all of the stuff of our present has come to seem precisely absurd: "family used to be blood, and that's who you lived with," says Latif Timbers, a gestation care coordinator: "people were really trying to get rid of that system with the communes." Timbers wonders: "Why would it matter so fucking much who gave birth to you? Or who you fell in love with or who happened to have the same parent. Like, what if those people were straight up assholes? Or just didn't know how to take care of you?"7 In the communes envisioned here, precisely because the primary compulsions of daily life are not economic ones, the possibilities for human relationships are expanded. Couples are not only oriented toward their households, and in turn, for children, regardless of whether relationships with first parents are central to you, or safe for you, your needs will not go unmet.

***

Something else, finally, shaped my thinking too, as I was reading Everything for Everyone, and attending "the family problem" seminar, and following the debate about Starr's comics. I was mourning the loss of my own mother, who had died after struggling with alcoholism for a long time.

Visiting my dad in BC soon after, I found a grocery store cake in the fridge, untouched and covered in a hard plastic dome. A novelty ring decorating the top read "Best Mom Ever." She had bought this cake herself, preparing to mark Mother's Day with my brothers perhaps, or maybe it was one of her countless covers: she would drink alone, hiding, and was ashamed to go out just for alcohol. She needed to act as though she had an errand to run, coming home with items she didn't need and never used, hoarding clothing, jewelry, and make up.

I have since spent a lot of time sorting through these items. They have all been lovingly curated, washed and pressed, folded, stored. In a recent reflection on his father's hoarded collections, Jon Day describes the psychology of hoarding as "fecund and generative." Organizing a hoard requires a great deal of labor. "It demands to be handled, shuffled, arranged, rejigged."8 It gave my mother something to do. Was it a way, also, of preparing for a life she didn't have — ready at any moment to fit an image of what she thought a woman's life should be? Having it all, perhaps. "Best Mom Ever." She felt guilty about not being that person, and responsible. In one common treatment for addiction, you apologize to people you feel you have wronged. My mother told me that she regretted not having more time for me, and not being "fully herself" even when we were together. Only half lying, I told her I was fine. I told her it wasn't her fault.

I blame capitalism, no surprise — but specifically here, its private family household and gendered organization of work. My mother moved with my dad from Ontario to BC in the 1970s, and they soon had me and my two brothers to look after. She trained as a nurse and worked very hard jobs for very little pay. Among these, she did a stint in a hospital for people with severe mental illness; she was a homemaker, caring for disabled and elderly people, helping with housework, shopping, and personal hygiene; and before retirement she was a classroom assistant for children with special needs. She saw a lot of people suffer; she watched some become ill and even die. My dad, meanwhile, earned considerably more money working in an increasingly automated environment at the Pacific Press, printing and distributing Vancouver's daily newspapers.

My mom never spoke to me about the impact that the nature of her work had on her, or the disparities in their incomes, or anything else of that nature. Lost in my own world, I don't recall ever really asking. I think we all felt — my brothers and I, and our friends — like it was normal to be a burden to our parents. They were trapped inside, while we roamed the streets around our townhouse complex, busy with each other. We lived in a large neighborhood with hundreds of families, but the adults, all to our knowledge organized into married heterosexual couples, rarely socialized. Parents all seemed exactly like mine: house after house, after work there were chores to do and then time for a few drinks watching television. We dreaded becoming them, burdened by responsibility and family life. "All the same, but all in isolation," as Michèle Barrett and Mary McIntosh described in The Anti-Social Family, in which they lament naturalization of the idea that biological parents are alone responsible for their children's wellbeing.9

Most years at Christmas I travel to BC, with very little joy, propelled by some idea that this is what families are supposed to do. My mother always prepared a massive turkey dinner. She would struggle, sometimes cutting herself or falling over, sneaking away to drink, eating very little of anything she made. She would be bereft if we didn't follow through with the ritual, though: perhaps, understandably, "grasping at a chance of guaranteed belonging, trust, recognition, and fulfillment," as Sophie Lewis writes in her description of the "family dream."10 We grow dependent on the routines and structures of the organization of time within capitalist life. A person can't help but be emotionally devoted to it, in the absence of any apparent alternative, and in the face of tempting cultural messaging about the importance of motherhood and family life: the "'family' of ideologies," Kathi Weeks calls them, constructing subjectivities that will submit to exploitation.11

As we see so starkly in Starr's response to the critics of her comics, you are not allowed to be "ungrateful." You must always swear to privilege and protect the family home. These culturally dominant idealizations and pressures profoundly mediate — morph and contort, shape and dilate — how we experience love, connection, intimacy, proximity, care. In their tendency to evade totalizing social critique, and to romanticize equalitarian households or non-heterosexual couplings as the liberatory alternative, the cultural forms of heteropessimism less remedy this dominant sensibility than they register — however dissenting and annoyed — the feeling of being stuck within it.

When my mother retired and we all moved out, she didn't quite know what to do with herself. She described it once as feeling like she was adjusting to losing a limb. As I recall it, it was then she started drinking. I saw some of her addiction recovery scripts, or heard her attending online meetings and therapy sessions, addressing a feeling of worthlessness. They referred to her life's inherent value, which she seemed to struggle to believe in or feel. Through drinking she wanted to be numb I suppose, self-obliterating. I watched all this from the protection of distance, wanting to leave from the moment I was thrust into this atmosphere. I was angry, of course. I was also mournful — that she was given these two small spheres to act within, badly paid care work and our family household, and even though they were not enough, and hurt her even, they seemed to be all she had. It was designed that way.

You can be bereft when you lose something that wasn't that great to begin with — a truth that speaks to the family's "paradoxical existence," as Weeks describes, its contradictory depths "as a narrow prescription and variable instantiation, a social expectation and a personal choice, a vicious trap and welcome sanctuary."12 Looking back from the future imagined in Everything for Everyone, Abdelhadi explains how, once, "you were supposed to still do all the things everyone else was going while also raising the kid or kids, and everyone kind of questioned your work if that wasn't 100-percent true. If you couldn't do it all or have it all — which no one could."13 Perhaps my mother felt that, after her nursing jobs and housework and parenting, and now caring for my ailing dad, the disparate bits of our lives were never going to reconcile into that predominant image-ideal of the happy family. There was no way to go back and "do it all or have it all."

I can't imagine ever not lamenting the life my mother didn't get to have, and how that restriction affected all of us, including me. I will continue also to think of her as one among so many people propelled into this kind of tragedy. The tropes of heteropessimism certainly touch upon something of her experience: she was unfulfilled in her relationship; she faced all the disparities in expectation and household organization that heteropessimism identifies. But they are not sufficiently explanatory, if one's goal is to understand the forces that shaped the life with which she was presented, within whose limited scope she had to try to find the family love that is so often idealized in popular cultural images. It is even idealized in forms like Starr's comics, which, despite complaining about how exhausting it all is, cannot resist calling it all ultimately worthwhile, even indispensable.

My simple point again, then, is that heteropessimism is limited to the extent that it stops at "reinforcing the privatizing function" of the couple, to return to Seresin's language, by treating the puzzle of women's desire for men as the main issue, by failing to identify the role that the couple-based family household itself plays in personal and planetary misery, and then by fathoming transformation within the tiny unit of the couple as the only grounds for any progressive activity. One can identify with aspects of heteropessimism and still be engaged in looking toward the revolutionary horizon, of course. Yet so many of its expressions do the opposite, rooting people even more in the social worlds that they already inhabit, offering the consolation of complaint about what is hardly, actually, unmovable.

Sarah Brouillette (@brouillettese) is a Professor in the Department of English at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada.

References

- Asa Seresin, "On Heteropessimism," The New Inquiry, October 9, 2019.[⤒]

- Asa Seresin, "Heterofatalism on TV," Vimeo, April 16, 2021.[⤒]

- I wish to thank Sarah Jaffe for a conversation that clarified my thinking on this topic. Sarah Jaffe, "This Valentine's Day, Let's Look to the Marxists to Reimagine Love, Romance and Sex," In These Times, February 14, 2023.[⤒]

- "Parapraxis Seminar One: The Problem of the Family; Meeting Nine: Sophie Lewis," YouTube, August 28, 2022.[⤒]

- Kathi Weeks, "Abolition of the family: the most infamous feminist proposal," Feminist Theory (2021): 1-21.[⤒]

- M.E. O'Brien and Eman Abdelhadi, Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune 2052-2072 (Common Notions, 2022), 32.[⤒]

- O'Brien and Abdelhadi, Everything for Everyone, 180.[⤒]

- Jon Day, "Hoardiculture," London Review of Books, September 8, 2022.[⤒]

- Michèle Barrett and Mary McIntosh, The Anti-Social Family (Verso, 1982), 58.[⤒]

- Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation (Verso, 2022), epub.[⤒]

- Weeks, "Abolition of the family," 2.[⤒]

- Weeks, "Abolition of the family," 5.[⤒]

- O'Brien and Abdelhadi, Everything for Everyone, 199.[⤒]