Stuckness

An icebound ship is a stuck ship — or so Heroic Age polar exploration accounts would have it. The best-known facts about the best-known historical polar expeditions (the Northwest Passage voyage launched by John Franklin in 1845 and the Antarctic venture undertaken by Ernest Shackleton in 1914) are that crew members were compelled to abandon their ships after they were immobilized or crushed by ice. Even when historical Arctic expeditions led by British sailors or other Qallunaat (Inuktitut for white or other non-Inuit people) intended to overwinter in the ice, ideally in a protected harbor, conditions remained unpredictable, and a stuck ship was under threat of being staved.

Yet sea ice is always in motion. Ice conditions that are experienced as static or threatening for Qallunaat are mobile and generative for Inuit and other circumpolar natives: whether the cryosphere is understood to be forbidding or hospitable to human thriving is largely a matter of latitudinal perspective. The life-sustaining imperative of ice for Inuit and other Indigenous Northerners, as well as the profound cultural, social, and subsistence challenges to their communities that arise from the loss of ice, have begun to be recognized by those Qallunaat raising the alarm in the industrialized world over accelerated melting and its effects on planetary albedo and sea levels. But these, of course, are not just contemporary concerns, as the history of Qallunaat maladaptation to Arctic conditions demonstrates.

This essay dilates on stuckness in ice, both in the nineteenth century and today, through a meditation on the speculative Arctic exploration horror of the 2018 AMC miniseries The Terror (showrunners David Kajganich and Soo Hugh), which concludes with a remarkable and revisionary shot of Arctic stasis. The miniseries' final shot reframes existing Qallunaat perspectives on stuckness in circumpolar practice, and in doing so, illustrates one form of white adaptation to Indigenous Ecological Knowledge. I have experienced my own version of circumpolar stuckness, both as a transit problem and an intellectual one. (I am a white American whose time in Inuit Nunangat includes sailing through the Northwest Passage and making a brief stop in Gjoa Haven [Uqsuqtuuq], "Land of the Franklin Expedition.") My Arctic travels to Nunavut have underscored the structural impossibility for Qallunaat — whether in the fictional Terror or my own personhood — to have a non-extractive relationship to Inuit knowledge.

The Terror is a ten-part AMC miniseries adapted, with a few key changes, from the 2007 historical fantasy novel of the same name by Dan Simmons (my subsequent references to The Terror are to the miniseries, not the novel, unless otherwise indicated). The Terror speculates on the fate of the real-life ship Terror, which along with flagship Erebus was one of two vessels lost in the Arctic in the midnineteenth century by the men of the British Northwest Passage expedition.

Both the known and the unknown stories of the historical expedition, including the loss of both ships and the deaths of all 129 of its members, have been of titanic interest since the midnineteenth century. Launched by Sir John Franklin in 1845, Erebus and Terror were caught in heavy ice off King William Island (Qikiqtaq) for two years without a summer thaw. In 1848, the 105 men who were still alive abandoned the icebound ships and tried to walk out of the Arctic archipelago; no crew members are known to have survived the final desperate march in search of rescue. Diminished by exposure, starvation, and lead poisoning from poorly-soldered food tins, the men ate some of their companions and scattered the terrain with their imperial detritus, items later recovered by Inuit. The only written records left by the British men of the fate of the expedition at the time of the abandonment of the ships were found in two brief notices left in cairns; they indicate that commander Franklin died of unknown causes a year before his second in command, Francis Crozier, made the decision to forsake the stuck ships.

I should note here that when the novel was published in 2007, searches for the Erebus and Terror had been steadily, futilely ongoing for 159 years. Just a decade later, when the miniseries was in production, the long decades of Qallunaat search failure had resolved in the dramatic announcements of the identification of the seafloor locations of the Erebus (in 2014, by Parks Canada) and the Terror (in 2016, by the private Arctic Research Foundation). The miniseries' popularity was likely driven in part by the media sensation generated by the archaeological announcements. But the location of the ships was only news to Qallunaat, whose long mystification was the result of not heeding Inuit knowledge that had relayed eyewitness accounts of the expedition's location since 1850. In fact, the Inuktitut name for an island near the Erebus's location is Umiaqtalik, which means "there is a boat there."1

The miniseries imagines the fate of the Franklin expedition after the ships are icebound, and the locus of perspectival orientation and narrative sympathy in The Terror is Francis Crozier (played by Jared Harris), an Irish captain who had previous Arctic experience and modest fluency in the Inuit language Inuktitut. The fictional Terror further supplements the scant historical record with a speculative account of what might have propelled (and doomed) the expedition's final, fatal march. In this version, the historical extreme weather, tainted meat, and British maladaptation to the Arctic are not the only antagonists: the men are additionally hunted by a monstrous Inuit spirit called Tuunbaq, which takes the form of an immense hybrid sort of polar bear and may or may not be controlled by Silna, a Nattilik Inuk woman whom the British men call Lady Silence. (There is no such spiritual creature as Tuunbaq in actual Inuit tradition.) But that is not all — the crew also unnecessarily suffers from the sociopathic machinations of a gay caulker's mate on the ship, Cornelius Hickey, who is a mutinous, eager cannibal.

It is a bummer in The Terror to encounter Tuunbaq (hostile, made-up Indigenous spirit) and Hickey (murderous queer cannibal). Both are a form of genre panic, as the true events of the Franklin expedition already amply bear the very horror encoded in the names of the ships Terror and Erebus (the latter ship was named for personification of darkness in Greek myth). These are unnecessary plot elements in an already sensational story, stereotypes that show how dramatic devices can get stuck on settler colonial and homophobic tropes. Both figures are involuted ways to represent the failure of Qallunaat men to survive in the Arctic not as a consequence of the choices and actions of blundering, temperate-zone colonizers, but as an effect of supernatural or "unnatural" forces. The effects of imperial encounter on Inuit have been poisonous enough historically.

Tuunbaq and other predators aside, the series is generally superb and worth your time. I am more interested, though, in how The Terror represents the variable understandings of stuckness at play in the mass casualty event that was the Franklin expedition. The British men were committed to forward motion, to passage, as the expedition had aspired to be the first to traverse the Northwest Passage — the sea route from the Atlantic to the Pacific via the Arctic Ocean, a fabled route not fully charted by Qallunaat and usually impassable because of ice. When the ships are first icebound in the miniseries, we see Franklin's acknowledgement that it will be difficult for the men to handle having their progress arrested by ice. He instructs his officers, "your demeanor should be all cheer, gentlemen, you understand. It's going to be tight but that's what we signed up for: an adventure for queen and country, an adventure of a lifetime. That's what you tell the men."2 Franklin (portrayed by Ciarán Hinds) explicitly links the ship's forward motion to their imperial imperative.

The imperial drive for passage animates one of the dramatic tensions in the early episodes of the series, when the devout Franklin's faith that the ships would be released from the grip of the ice runs up against Crozier's practical proposal to send a party to seek rescue rather than wait in place. Tactical differences notwithstanding, both men fear being stuck and wish to keep moving forward, although Crozier's willingness to violate orders and lead an escape pod party himself is disrupted in The Terror when Franklin is killed by Tuunbaq (the historical record confirms that Franklin died before the ships were abandoned, but gives no cause of death, whether at the hands of an amplified apex predator or otherwise).

The British men associate Tuunbaq's supernatural powers with Silna, an Inuk woman whom they encounter on the ice. Crozier's sympathetic role in the miniseries is indicated in part by his relative respect for the Inuit and his ability to communicate with Silna. But she has contempt for the British men's maladaptation to Arctic conditions, despite the shelter and affordances of their wooden ships; as she tells Crozier: "You use the wind to carry you here. You use the forest to hide inside. You use all this and don't even want to be here. You don't want to live."3Their loss of will to "live" is more than a consequence of harsh environmental conditions; it also reflects their refusal to learn how to "be here," to think of the Arctic as a place to live — as anything other than a transit for global commerce.

The death march of the sailors of Erebus and Terror, who man-haul heavily laden boats over the featureless scree of King William Island, underscores Silna's point. Why would the expedition members drag with them heavy, non-essential stores such as bone china, curtain rods, and a copy of The Vicar of Wakefield (fig. 2) (all items recovered by later search parties, historically speaking) if they understood their mission as an experiment in Arctic survival? That list of cargo makes sense only if they understood their mission as a form of cultural portage, a refusal to "live" as Inuit do, culturally and existentially. Even the death of the expedition's ice master, Blankey, who lures Tuunbaq to a shoreline away from the men late in their journey, is not sufficiently triumphal in his heroic sacrifice alone: Blankey is shown writing "NOR'WEST PASSAGE" on a map in gleeful hydrographic pride before the monster consumes him. The mythical completion of the Passage — the vision of Blankey filling in the blank spots on white maps — is held up as consolation for his gruesome end. The British men's grinding drive for passage was not all for naught, Blankey's map documents pointlessly; pyrrhic discovery is the Franklin expedition's only heroic sacrificial reward.

![A flattened, spine-up, leatherbound, nineteenth-century edition of Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield, with visible warping and water damage. The leather is blackened and the spine still shows gold embossing; some of the fascicle stitching of the pages is visible.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/blum-2.jpg)

But as imagined in The Terror, Crozier is the lone survivor of both Tuunbaq and the Arctic environment, and he survives because of his eventual rejection of Qallunaat practices and his embrace of Inuit knowledge. When the men were in the process of abandoning ship, Crozier still clung with them to the dross of their colonial lives, even as he recognized that the coffee cup saucers and tools would fall by the wayside: "Things will drop away. To ask these men to see these bits of who they are as one more threat to them . . . no," he muses.4

In the final few minutes of the miniseries, in an episode entitled "We Are Gone," Crozier himself is shown to have dropped away from Qallunaat things. It is two years later; Crozier (known to the Inuit both in the miniseries and in real life as Aglooka [Aglukaq] or Long Strider) is now living with a small community of Inuit with whom he communicates fluently and shares the responsibilities of hunting and other labor. He and the others easily pull lightly-laden sleds of provisions, in contrast to earlier scenes where he engages in the Qallunaat practice of wildly overburdened hauling. When a Franklin search party comes across their encampment, Crozier conceals himself from the British men and asks his Inuk companion to say that he, Crozier, had died in Inuit company and had wished to pass along a message to any who came looking for him: "tell those who come after us not to stay. The ships are gone. There is no way through, no passage. Tell them we are gone."5. Crozier has undergone a perspectival reorientation from an explorer in need of rescue to an Arctic resident refusing further Qallunaat incursion. He rejects, too, the British notion of passage: there is "no passage," only Arctic stasis — which for Crozier has new meaning.

Crozier's perspectival reorientation is in turn passed along to the viewer in the series' stunning final shot, a long, slow zoom outward from a nearly-still image (figs 3-4). We see a bearded Crozier wearing an Inuit-style sealskin anorak while crouched over a seal hole in the ice, a harpoon balanced in his hands. A child of around five or six years (too old to be his own child) naps comfortably at his side, an indication of the white man's integration into the community. Crozier sits motionless for the static final minute or two of the episode — no longer stuck, but in patient equilibrium with Arctic ice and its life-giving affordances. This is not an easy life, as Crozier's vigil at the ice hole makes clear. But it is a life that understands the human relation to Arctic conditions as mutually sustaining rather than antagonistic.6

In explaining the series' final scene, showrunner David Kajganich emphasizes that "this was not an exotic choice, this was not a mythical choice, this wasn't a heroic choice — [Crozier's] life was going to be very very hard."7 Even so, he clarifies in another interview, "at least it's a life with people who are more honest about their motivations and have more of a sense of community than he'd go back to if he went back to London."8 What redeems this choice — what elevates it beyond cliches of gone-Native purity versus colonizer decadence — is its insight into the chasm between Inuit and Qallunaat understanding of ice. "There is no way through, no passage," Crozier had communicated to the search parties in The Terror. For British navigators this untruth might be a deterrent to future travel to the North, as Crozier intends it. But for those who for thousands of years have known the Arctic as home — not as a throughway or passage for global transit — "no passage" might resonate differently.

![a television still of Jared Harris as Francis Crozier, wearing a hooded sealskin anorak and heavy gloves, holding a harpoon, sitting on his heels over a seal hole in the ice, while an Inuk child of about five or six naps at his feet in furs. This is a zoomed-out perspective of fig. 3, and the sea ice is here more visible around the figures.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/blum-4.png)

In this sense, stuckness in The Terror is not just a function of immobility versus motion, but a function of duration. As scholars of temporality have shown, the progressive linear time of nations is out of joint with other conceptions and experiences of duration, including the duration of Inuit survival.9 The challenges of thinking about presence, futurity, and Indigeneity are expressed succinctly by Mark Rifkin: either Indigenous people "are consigned to the past, or they are inserted into a present defined on non-native terms."10 The Franklin expeditions and the scores of search parties that followed it over many decades may have bridged a specific, significant timeline in Qallunaat history and knowledge of the North, yet Inuit survivance in the North is keyed to a different timescale: the timescale of the practice and production of Indigenous or Traditional Ecological Knowledge, in which experiential information accrued year after year holds far more significance than the exceptionalism of any exploring expeditions.

The continuities and placedness of the practice of Inuit knowledge are the very key to its power. The history of the Franklin expedition reflects a settler colonial partiality for the progressive and original over the supposedly rote, repetitive, or traditional. Similarly, in dismissing the importance of Arctic situated knowledge, histories of the Franklin expedition replicate a longstanding tendency for settler colonial writers to consign Indigenous people to antiquity, obsolescence, or other forms of the past, making neither rhetorical nor socio-political space for Indigeneity in the present or future. Indigenous Ecological Knowledge is recursive but not static; its cycles ebb and flow and adapt over time.

***

All towns in Nunavut, the territory that encompasses much of the Arctic archipelago claimed by Canada, are fly-in hamlets, accessible only by plane or by boat in summer. I wrote some of these words in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut. In the parlance of contemporary air travelers, I was stuck there an extra two days beyond my original booking. The flight I had planned from Iqaluit to Kinngait (the former Cape Dorset, known for Inuit printmaking) was canceled, and the route is not flown every day; when I did make it to Kinngait several days later, the Kenojuak Cultural Centre and Print Shop was closed for the weekend and I never managed to gain access.

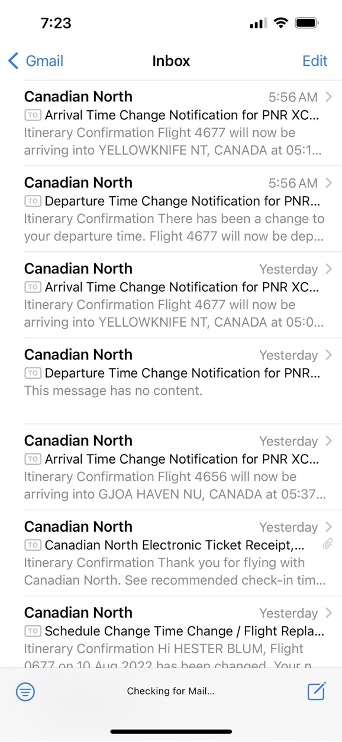

In planning a two-week research trip to six hamlets across Nunavut and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories, I had been cautioned to expect delays and cancellations to my various Canadian North flights as a matter of course for Arctic travel (fig. 5). I have encountered travel complications repeatedly in previous polar trips: my Northwest Passage expedition was postponed several years in a row and included the near-catastrophic grounding of one ship in the high Arctic; a venture to Svalbard that I made in 2022 had been postponed three times because of Covid. I thought I had adjusted my American impatience in advance of this trip, ready to roll with contingencies, yet the first thought I had after the cancellation was that I was stuck here. Stuck, here, where I had been passionate to travel for years, eager to snuff Arctic air and tread Arctic tundra and listen to Arctic knowledge. Stuck was my first thought, not gifted with more time in Iqaluit.

My subsequent travel to Gjoa Haven, "Land of the Franklin Expedition" according to the sweatshirts for sale at the Qikiqtaq Co-Op, was no less a reminder about the contingencies of Arctic time and passage for a Qallunaaq traveler. The hamlet's only hotel did not have a working vehicle, for instance, and I thought I'd get stuck there, too, after trying and failing to pay teens on quads to run me to the airport before my departing leg; I made it to the flight only after the manager of Canadian North's western division noticed that I — a conspicuously tall fellow white woman — was not yet at the airport and sent the lone ticket counter worker over in a pickup to look for me. In the bay in Gjoa Haven I saw a barge loaded with several green containers, likewise conspicuously tall compared to the residents' fishing boats (fig. 6). It was the Qiniqtiryuaq, I was startled to realize, the research barge from which Parks Canada has launched its underwater archeological exploration of the wrecks of the Erebus and Terror in the past few years. The ice had recently melted and the dive season was soon to begin. Nunavut Inuit have rights of access for harvesting or hunting in the area of the wrecks, per the Nunavut Agreement. But the location of the two ships on the seafloor off King William Island is otherwise shielded by Inuit guardians, who watch to ensure that outsiders not authorized by Nunavut or Parks Canada do not access the heritage sites and extract artifacts or other resources.

![A photo of a bay shoreline, with a sandy beach crossed with ATV tracks in the foreground, and a research barge moored to the shore in the center of the image. The barge is labeled Qiniqtiryuaq and three green shipping containers are visible on its deck. Modular buildings are visible in the background on the ridges of Gjoa Haven.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/blum-6.jpg)

I end this piece on stuckness with an artifact of my time in Gjoa Haven that illustrates the impossibility of my having an epistemological relation to Inuit knowledge that is not just another extension of extractive Qallunaat settler logics. I had visited the Ullaluq Inuit Arts shop and the superb Nattilik Heritage Centre, which tells the history of the Nattilik Inuit through stories, art, tools, and other crafts. It also displays a series of text-based installations on the Franklin ships and the search history. Textile art is a specialty of the hamlet's artists, and in the art shop I was struck stock-still by the tapestry work of Helen Kaloon, particularly a large textile she made of the Erebus after it had been forsaken by the Franklin expedition members (fig. 7).

![a photo of a large felted and embroidered wall tapestry hanging from a wooden rod. The background is cream-colored canvas, and on a field of black, with brown, white, and tan accents, the artist Helen Kaloon has represented the icebound wooden ship Erebus, its masts slightly askew and a tarp still raised over its deck for overwintering; the shrouds are rendered three dimensionally. A party of five Inuit are depicted taking usable items from the ship and carrying them away on a sled that had been loaded heavily enough that one Inuk is shown half-bent from the weight.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/blum-7.jpg)

The tapestry shows the icebound wooden ship, its masts slightly askew and a tarp still raised over its deck for overwintering; the shrouds are rendered three dimensionally. A party of five Inuit are depicted taking usable items from the ship and carrying them away on a sled that had been loaded heavily enough that one Inuk is shown half-bent from the weight. It is an astonishing illustration of Inuit accounts of the aftermath of the ships' abandonment: an oral history rendered in fiber art, a visual representation of the knowledge of the ships' fate held by Inuit (and dismissed or misread by Qallunaat) for nearly 175 years. I purchased it. In buying Kaloon's art, I wondered if the Inuk woman who facilitated the transaction saw me as just another extractive Qallunaaq visitor to the North, one whose acquisitive artistic interest was not in the other Kaloon tapestries for sale that showed ongoing Inuit cultural practices, but in the Franklin story, always the Franklin story.

She would have been right to see me thus, for the research and reading methodologies I have been taught and have continued to practice as a white American Qallunaaq are fundamentally extractive. When I had traveled through the Northwest Passage in 2019, I was the only humanities scholar on the scientific research expedition. One of the American student scientists had described my humanities methodology by saying "you spend your life collecting stories." He intended this as a compliment, and at the moment I took it as such. But as my conversations with the Inuit researchers on that expedition (and subsequent study) has come to make me realize, "collecting stories" can be its own form of resource extraction — intellectual resource extraction rather than fossil fuel. As Max Liboiron has suggested, "reading ethically can mean refusing to read as a form of extraction."11 Humanists might "collect stories," but in order not to replicate histories of settler resource appropriation or extraction through the accumulating value, sometimes those stories should stick in place.

Hester Blum (@HesterBlum) is Professor of English at Penn State University. She is the author of The News at the Ends of the Earth: The Print Culture of Polar Exploration (Duke 2019) and The View from the Masthead: Maritime Imagination and Antebellum American Sea Narratives (UNC 2008), and the editor of a new Oxford edition of Moby-Dick (2022), among other volumes. She has participated in several research trips to the Arctic and Antarctica, and her awards include fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. She is currently writing a book about the temporalities of polar humanities scholarship entitled Polar Erratics: In and Out of Place in the Polar Zones.

References

- The success of the twenty-first century searches was made possible only by belated Qallunaat partnership with Louie Kamookak and other Inuit oral historians; even so, Parks Canada and other search teams ignored local Inuit stories not just in the nineteenth century searches but throughout the contemporary search period. The advent of ROV submersibles aided these searches, but their success still relied on Inuit consultation.[⤒]

- The Terror, 2018-2019, Season 1, Episode 1, "Go For Broke," directed by Edward Berger, aired March 25, 2018 on AMC[⤒]

- The Terror, 2018-2019, Season 1, Episode 5, "First Shot a Winner, Lads," directed by Sergio Mimica-Gezzan, aired April 16, 2018 on AMC[⤒]

- The Terror, 2018-2019, Season 1, Episode 7, "Horrible from Supper," directed by Tim Mielants, aired April 30, 2018 on AMC[⤒]

- The Terror, 2018-2019, Season 1, Episode 10, "We Are Gone," directed by Tim Mielants, aired May 21, 2018 on AMC[⤒]

- The ending to the miniseries is a welcome departure from the novel, which concludes with Crozier as a telepathic, shamanistic, gone-Native lover of Silna.[⤒]

- Haleigh Foutch, "'The Terror' Showrunners Break Down Key Moments from That Stunning Season Finale," Collider, May 22, 2018: https://collider.com/the-terror-ending-explained/.[⤒]

- Tim Surette, "How The Terror Became One of TV's Best Horror Series," TV Guide, May 21, 2018: https://www.tvguide.com/news/the-old-man-season-2-premiere-date-cast-and-more/.[⤒]

- The temporal regimes against or outside of which Indigenous time functions can been variously described as nation time (see the work of Lloyd Pratt); settler time (Kyle Powys Whyte, Mark Rifkin); professional time (Caroline Dinshaw); homogenous, empty time of capitalism and nations (Walter Benjamin, Benedict Anderson); secular time (Dipesh Chakrabarty); and chrononormativity (Elizabeth Freeman, Dana Luciano).[⤒]

- Rifkin argues that asserting Native presence within the contemporary is a concession to settler time, rather than Indigenous forms of temporal understanding. Mark Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), vii.[⤒]

- Max Liboiron, Pollution is Colonialism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).[⤒]