Stuckness

Last January, in yet another sign, perhaps, of the shifting weather patterns and intensified storm systems caused by global warming, a fierce snowstorm stranded hundreds of motorists along a 50-mile stretch of Interstate 95 in Virginia. Rain, followed by iced-over roads, high winds, and blowing snow caused a series of collisions, rendering the highway impassable. People found themselves stuck in traffic for more than 24 hours. As temperatures fell to below freezing overnight, those stranded in their cars kept their motors running to keep warm; but as the ordeal wore on, many ran out of gas and were left without food or water.

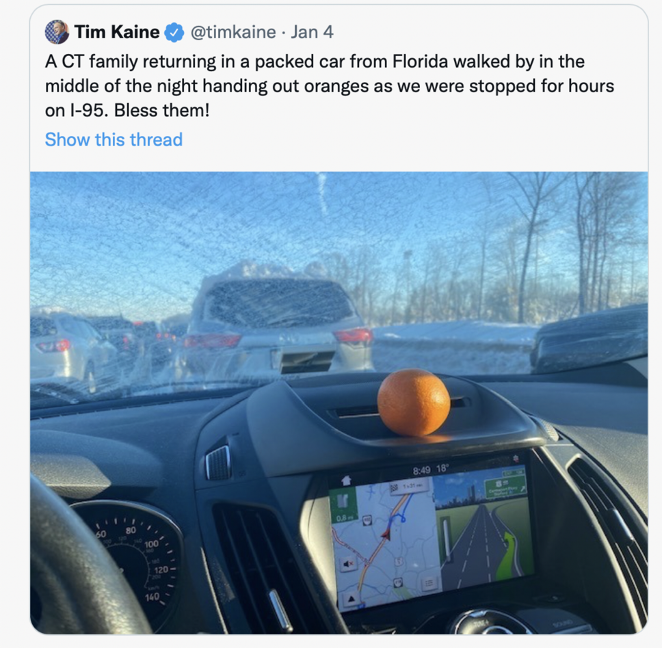

During and after the ordeal, news outlets ran profiles of some of the commuters: truckers, families, and individuals forced to endure the snarl as well as the cold and the hunger.1 Reporters were especially quick to identify and interview Virginia Senator Tim Kaine, whose ordinary commute to his office in Washington D.C. placed him among those stuck in the bottleneck. "This has been a miserable experience," Kaine said afterward, "but at some point I kind of made the switch from a miserable travel experience into kind of a survival project."2 The morning of the second day of the Virginia traffic jam, Kaine tweeted about an act of kindness that took place overnight: a family traveling home to Connecticut from Florida walked through the rows of vehicles and passed out oranges to the hungry (fig. 1).3

When I saw Kaine's photo of an orange carefully placed on his car's dashboard with rows of taillights receding into the distance, I couldn't help but think of another traffic jam: the one at the center of Karen Tei Yamashita's inventive 1997 novel Tropic of Orange. The vehicular clog in Tropic of Orange is caused when two men peeling oranges in a Porsche on a Los Angeles freeway collide with a semi-truck, leaving hundreds of cars stacked up and jumbled together on the interchange. The orange in Kaine's photo, both out of place and out of season in a Virginia winter snowstorm, echoes the titular orange of Yamashita's novel. It is the product of a tree planted in Mazlatan, Mexico precisely on the Tropic of Cancer — the imaginary line that marks the northernmost point at which the sun is directly overhead and hence the northern boundary of the tropics — that blooms too early and too little, bearing a single orange.4 Remarkably, when transported north, the orange brings the Tropic of Cancer with it. The orange thus attests to the ways a changing climate shifts and remakes our borders, weather patterns, and human populations alike.

But if Tim Kaine's orange might likewise betoken the climate crisis, his survival on that Virginia interstate hardly depended upon that piece of fruit. Kaine's rendition of his experience as not just a miserable experience but a "survival project" casts his 24-hour travail as something out of a post-apocalyptic zombie film, when in fact the US senator was in constant cell phone contact with state officials. Intensifying the drama of his experience, Kaine's account obscures the fact that the ordinary smooth operation of infrastructural systems has long been experienced very differently by people across populations. Which is only to say that, while restoring the flow of traffic on I-95 was surely a relief to Kaine and the hundreds of other motorists stranded overnight, one might question the degree to which removing impediments to the free flow of gasoline-fueled vehicles was good for everyone and everything. Or to put this somewhat differently, like Senator Kaine, sooner or later we will all (if we have not already) find ourselves stuck in traffic. But — and this is the point I mean to pursue here — we won't all be stuck in the same way.

In this short essay, I want to develop this point by turning to another novel, both contemporary with and complementary to, Yamashita's: Helena Maria Viramontes's rich, beautiful novel Under the Feet of Jesus. Like Tropic of Orange, Under the Feet of Jesus features characters who find themselves stuck in traffic, albeit differently so. Focusing on this feature of the novel, I treat it as a work of petrofiction, one that has much to say about racialized extractive capitalism and about how oil and its appurtenances — especially automobility and infrastructure — shape and sustain inequalities and disparate experiences, the unevenness and injustice produced by petromodernity.5

Let me begin by clarifying my two key terms. By "traffic" I don't just mean the flow of vehicles over roads and freeways. I take traffic also as a synecdoche for modern petroculture and especially for the infrastructures that serve, sustain, and help organize it. To say that we are stuck in traffic is to say that we are stuck in petroculture, in the world made by hydrocarbons, which has in turn made us who we are. By stuck, then, I mean to identify the condition that Imre Szeman and Mark Simpson in a recent essay term "energy impasse," which they argue constitutes "the defining condition of our time."6 By "impasse," Szeman and Simpson mean something other than just the kind of blockage we see when a jack-knifed semi-trailer arrests the flow of traffic. Instead, they describe impasse as "stuckness," which they define as "the texture or atmosphere setting the conditions of possibility for a given situation that, irrespective of any overcoming of actually existing blockages, manages nevertheless to perpetuate the situation as it is."7 In other words, while tow trucks and snow plows from the Virginia Department of Transportation eventually managed to clear I-95 of obstructions, we're really no less stuck in traffic than before, and not just because there is always another interstate snarl. We can always figure out ways to get cars moving on the freeway again, but we seem unable to imagine a world in which getting cars moving on the freeway again is not an imperative.

Consider, for instance, the public discussion in the aftermath of the Virginia traffic jam. Politicians and other observers viewed the incident as, in Kaine's words, "a good infrastructure story," the moral of which is that "we're just not as big investors in infrastructure as we should be."8 Here, Kaine, like others, understands infrastructure mainly as a problem of statecraft — or a problem, we might say, of what Keller Easterling calls "extrastatecraft." Whereas statecraft identifies the management of inert objects or systems by governments, extrastatecraft captures the ways that certain structures, designed to facilitate and advance the aims and objectives of fossil capitalism, function and are managed by extra-governmental authorities.9 Viewed in this way, "investment" in infrastructure means little more than providing the material conditions that make possible the unobstructed movement of people and goods. Thus the response to the Virginia bottleneck revolved around measures to deal with ever-increasing traffic congestion: more lanes on the freeway, better maintenance and upkeep, upgrades to road-clearing response processes, and perhaps even new investment in other forms of transit.

In other words, for Kaine, what constitutes "a good infrastructure story" ultimately seems to have less to do with miserable experiences (the making or unmaking of subjects) and more to do with administration (the management of systems and processes). This vision of infrastructure as statecraft is rendered vividly in the photographs of Edward Burtynsky. In his well-known series Oil, Burtynsky set out to represent what he describes as "the main basis for our modern industrial world": the automobile.10 To do so, he turned to sites of extraction and production, like oil fields and refineries, as well as the appurtenances and byproducts of automobility, such as bridges, highways, parking lots, dumps, and scrapyards, all of which help capture the scope, the scale, and the enormous waste of our auto-saturated world. Burtynsky's breathtaking, large-format images — taken aerially, typically, from hundreds of feet in the air — have at times been accused of lacking political force because they can seem to aestheticize ecological devastation. But as Michael Truscello has argued recently, the "distant view" of Burtynsky's photographs is best understood as the "cadastral perspective of the state."11 That is, like cadastral maps produced to survey and show the value of land, typically for purposes of taxation, the cadastral perspective of Burtynsky's images help reveal "the administrative logic of the state."12

Highway #1 (fig. 2), for example, shows the stack interchange (now called the Harry Pregerson interchange) in Los Angeles where highways 105 and 110 cross. The site was recently featured in the opening scene of the film La La Land, where its stalled rows of brightly colored vehicles become the site of an exuberant musical dance number: celebrated rather than bemoaned, the traffic jam provides the occasion for the making of theatrical art. In Burtynsky's image, the scene is less colorful, but no less stirring. The two major arteries bisect the frame horizontally and vertically, while numerous other ribbons of concrete curve and sweep and loop above and around them. Concrete overwhelms the grid of the city in the background of the top left and right of the frame, and overpowers the landscape in the foreground, where a smattering of remaining trees poke up in the spaces between the on- and off-ramps, like weeds. Burtynsky's image renders a different sort of choreography, no less elegant, elaborate, or remarkable than La La Land's: a dazzling performance of modern techno-engineering. Traffic, in Burtynsky's image, is almost beside the point. Strikingly few cars (especially for Los Angeles) dot the photograph's lattice and swirl of roads and freeways. Free of congestion, Highway #1 thus stages for the viewer the technocratic state's version of what infrastructures promise to make possible, just as La La Land transforms the traffic jam from aggravation to joy. We hate it. But we love it.

The trouble of course, is that the enabling conditions of the flows of traffic and capital are often obstructions for others. Which is just another way of saying that as much as infrastructures make some things possible, they make other things, as we'll see in a moment, impossible.13 Moreover, infrastructural systems are more than just physical modes of conveyance.

They produce other effects, and affects, as Burtynsky suggests with his presentation of the stack interchange. The infrastructural theorist Brian Larkin makes this suggestion, too, when he observes that infrastructures are not just "built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas;" they are also forms that "encode the dreams of individuals" and help shape our desires and fantasies.14 What makes a traffic jam an enervating, sometimes harrowing, experience, in other words, is not just the prospect of arriving at one's destination late, or something worse, like running out of gas or food or succumbing to freezing temperatures in a freak winter snowstorm. It's also a matter of thwarting our desires, habituated and reinforced by our expectations, if not our actual experiences, of those same infrastructural systems (like roads and freeways), of speed, freedom, and unconstrained mobility. Hence it is also a matter of puncturing our fantasies of free and unencumbered selfhood, our understanding of ourselves as actors who move upon roadways, rather than subjects who are moved, both physically and affectively, by them. Thoreau made this point pithily in Walden almost two centuries ago: "We do not ride on the railroad," he famously wrote, "it rides upon us."15 Or as Larkin puts it, infrastructures form us "as subjects not just on a technopolitical level but also through this mobilization of affect and the senses of desire, pride, and frustration, feelings which can be deeply political."16

In Under the Feet of Jesus, Viramontes illustrates Larkin's "mobilization of affect" through what amounts to an inversion of Burtynsky's Highway #1. Rather than the distant cadastral view of the state, Viramontes provides a series of vivid depictions of what I'll call infrastructural intimacy — novel affective experiences of infrastructure generated by proximity. It's something of a rule of thumb, after all, that one can measure the differential distribution of the harms and benefits of infrastructures simply by way of closeness; it's not the affluent who are surrounded by petrochemical refineries or have interstate highways running through their front yards.

Much of Under the Feet of Jesus, about a family of migrant farm workers, takes place in California's vineyards and orchards (the young protagonist Estrella's most powerful childhood memory is of her father peeling an orange illicitly plucked from a tree — a reminder of the racialized capitalist exploitation that Tim Kaine's feel-good story obscures. But the narrative also flashes back occasionally to the family's life in Los Angeles, where the freeway system forms an important backdrop, invoking the mid-twentieth-century history of California freeway expansion that disrupted and displaced Chicana/o communities, especially in East Los Angeles.17 Those scenes vividly reveal the uneven experiences across populations that infrastructure affords.

One of these scenes, for instance, forms a striking contrast with Burtynsky's Highway #1. Where that photograph positions the viewer high above the interchange, safely distanced from the noise and smoke and velocity of a busy freeway system, Estrella's family experiences the interchange (most likely the East LA Interchange in Boyle Heights, rather than the Pregerson) from below — literally. The experience is frightening, "a car wreck waiting to happen," as Estrella's mother Petra says:

Estrella's real father looked up at her as he pulled out the old shoelaces. The freeway interchange right above their apartment looped like knots of asphalt and cement and the cars swerved into unexpected steep turns with squeals of braking tires. Sunlight glistened off the bending steel guardrails of the ramps. Just you wait and see, Petra said in a puff of breath on the window glass, a car will flip over the edge.18

In contrast to the loops and knots of Burtynsky's image, which produce awe and wonder, Viramontes renders an experience of the interchange that is as intimate, as tactile and proximate, as tying one's shoes. Yet the experience is also terrifying, the vehicles so near that their movement feels threateningly precarious, a danger only intensified by the sounds (squealing tires) and sights (the sunlight on the steel guardrails) of the scene overhead.

Nor is this the only instance in the novel of the freeway as a kind of peril. Later in the novel, Petra, Estrella, and her brothers attempt to leave the orchard where they are working to visit a convenience store across the highway. The scene explicitly contrasts the cadastral perspective with what we might call the menacing infrastructural intimacy Petra and her family experience. "Petra knew," Viramontes writes, that "the capricious black lines on a map did little to reveal the hump and tear of the stitched pavement which ascended to the morning sun."19 As the family approaches the main highway, they "could feel the heat pulsating from the asphalt" and they see "the oil of the pavement mirrored like puddles of fresh rainwater though it hadn't rained in months."20 Among the more powerful insights of infrastructure studies is the way that infrastructures shape embodied experiences and "produce," as Larkin puts it, "the ambient conditions of everyday life."21 But what makes the scene in Under the Feet of Jesus so wrenching is its rendering of a set of ambient experiences not ordinarily associated with petroculture and automobility and their promise of acceleration, speed, power, and free movement. When we think of roads and highways, in other words, we tend to think of what happens on them, not below, beside, or in them. Automobility largely distances us, abstracts us, from the material substances out of which infrastructures are made.

So Viramontes offers a very different experience of being stuck in traffic, one predicated not on infrastructural failure — the ostensibly anomalous situation where traffic has been temporarily arrested — but on infrastructure's ordinary smooth operation — the free flow of traffic. Viramontes takes us out of those vehicles and positions us with Estrella and her family, stuck by the side of the road, threatened by an "Allied Moving truck which whisked by with such incredible speed, it forced the hems of dresses up and shirts to fly open" or by "a convoy of vehicles appear[ing] from nowhere, whipping their faces with grainy wind," while "far across the highway, the rickety store stood as desirous as a drink of water."22 From this perspective, one feels not the sensation of rubber gliding on asphalt (petroleum on petroleum), but instead a striking instance of touch. Waiting in the heat for the chance to cross, Estrella "sunk her white thumbnail into the pavement and slowly sliced a sliver on the melted tar."23 How many of us have had such an intimate sensory experience with an asphalt freeway?

Viramontes provides another example of this intimacy in a different scene. This one, too, features an unconventional experience of automobility. On an unusually hot day in the orchards, the workers take a break from work, seeking shade under tarps and the canopies of trees. But Estrella finds relief from the heat underneath a truck, where her friend Alejo finds and joins her, both of them positioning themselves to avoid oil dripping from the radiator above. The leaking oil leads Alejo, who dreams of becoming a geologist, to ask Estrella if she knows here oil comes from. Estrella wonders why he asks, so Alejo explains, "If we don't have oil, we don't have gasoline." "Good," Estrella replies, "We'd stay put then." Having lived most of her life on the move, for Estrella staying put means stability; she associates automobility not with freedom, but with migrancy. But Alejo has more worldly ambitions and so attempts to correct her. "Stuck, more like it," he says. "Stuck." To which Estrella responds pointedly, "Aren't we now?"24

Estrella's rejoinder suggests that — occasional traffic jams aside — many of us don't really know what it's like to be stuck; or, at least, that we misapprehend our stuckness. Oil and gasoline have got us all, but they've got us all differently. "Petroleum infrastructure," Stephanie LeMenager asserts in her now classic Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century, "has become embodied memory and habitus for modern humans"—which is to say that in a very real way, we are stuck in ourselves, the selves made by petro-modernity and its material instantiations.25 Thus for LeMenager, "decoupling human corporeal memory from the infrastructures that have sustained it may be the primary challenge for ecological narrative in the service of human species survival beyond the twenty-first century."26 A novel like Under the Feet of Jesus can help us meet this challenge by reminding us that our embodied experiences, our "incorporating practices" are far from uniform and, hence, far from inevitable and far from immutable.27 And in that way, it reminds us that we should probably worry less about what those of us who yet remain relatively safe (though not for long!) from the worst effects of our overheating planet might stand to lose by becoming unstuck and think more about what those who have been excluded from petroculture's blessings and harmed by its excesses might stand to gain.

Jeffrey Insko (@jeffreyinsko) is Professor of English at Oakland University in Michigan, where he teaches courses in 19th-century US literaure and culture and the Environmental and Energy Humanities. He is he author of History, Abolition and the Ever-Present Now in Antebellum American Writing (Oxford 2018) and the editor of the Norton Library edition of Moby-Dick (2023). He is currently writing about oil, extraction, infrastructure, and the environment.

References

- See, for example, Christina Cauterucci, "'Everything Was Cool Until We Got Into Virginia'," Slate, June 4, 2022: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/01/trucker-stuck-on-i95-virginia-highway-snow.html; and "Family Stranded in Virginia: 'It's Not Getting Any Better'," US News and World Report, June 4, 2022: https://www.usnews.com/news/us/articles/2022-01-04/stranded-on-virginias-roads-its-not-getting-any-better.[⤒]

- Kevin Breuninger, "Senator Tim Kaine arrives in D.C. after being stuck in a winter storm traffic jam for 27 hours," CNBC, January 5, 2022: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/04/sen-tim-kaine-among-hundreds-trapped-in-virginia-snowstorm-traffic-jam.html.[⤒]

- Breuninger, "Senator Tim Kaine."[⤒]

- Karen Tei Yamashita, Tropic of Cancer (Coffee House Press, 1997), 11.[⤒]

- For a related reading of the novel, to which I am partially indebted, see Shouhei Tanaka, "Fossil Fuel Fiction and the Geologies of Race," PMLA (January 2022): 36-51.[⤒]

- Mark Simpson and Imre Szeman, "Impasse Time," South Atlantic Quarterly (January 2021): 79.[⤒]

- Simpson and Szeman, 80.[⤒]

- Breuninger, "Senator Tim Kaine."[⤒]

- Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure (Verso, 2014). [⤒]

- See https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/photographs/oil.[⤒]

- Michael Truscello, Infrastructural Brutalism: Art and the Necropolitics of Infrastructure (MIT Press, 2020): 179.[⤒]

- Truscello, Infrastructural Brutalism, 160.[⤒]

- Here, I am paraphrasing Easterling who observes that "the medium of infrastructure space makes some things possible and other things impossible."[⤒]

- Larkin, "The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure," Annual Review of Anthropology (2013): 328, 333.[⤒]

- Thoreau, Walden.[⤒]

- Larkin, "Infrastructure," 333.[⤒]

- Viramontes's later novel Their Dogs Came with Them is even more explicitly about LA freeway expansion in the 1960s and 1970s. For a generative reading of that feature of the novel, see Jina B. Kim, "Cripping East Los Angeles: Enabling Environmental Justice in Helena Maria Viramontes's Their Dogs Came with Them," Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities, edited by J.C. Sibara and Sarah Jacquette Ray (University of Nebraska Press, 2017): 502-530.[⤒]

- Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus (Dutton Books, 1995): 16.[⤒]

- Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus, 103.[⤒]

- Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus, 103[⤒]

- Larkin, "Infrastructure," 336[⤒]

- Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus, 104.[⤒]

- Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus, 103.[⤒]

- Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus, 86.[⤒]

- Stephanie LeMenager, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (Oxford, 2016): 104.[⤒]

- LeMenager, Living Oil, 104. [⤒]

- LeMenager, Living Oil, 104.[⤒]