Issue 10: The Inaugural Prize Issue

One puzzle for future historians of the sensorium, if there are any left, will be the simultaneous sharpening and dulling of the human senses under the pressure of advanced climate change. Those who try to unravel this enigma could do worse than turn to the novel. Alexandra Kleeman's 2021 novel Something New Under the Sun starts off with the story of a mid-career novelist who sets off for Los Angeles to participate, somehow, in the production of a film based on his latest book. He sets off expecting Hollywood glamor, only to find that, for one thing, he has been assigned the lowly role of production assistant, and for another, LA is barely fit for human habitation. From the moment he touches down, "small plumes of smoke in the distance" start to edge their way into otherwise unrelated chunks of dialogue.1 The heat is deathly, choking. As if under its pressure, description itself seems to denature into a lazy haze:

The sky is blue but diluted by a grayish, brownish undertone that can be found everywhere and nowhere at once — like the halfhearted presence of his wife and daughter over text or phone, like the internet, like DDT, banned in the United States but increasingly prevalent in South America, Africa, Asia. Like the omnipresent Cassidy Carter: an ambient mechanical whine coming from somewhere deep within the house that, once heard, can never again be unheard .... He is light and heavy, sunburny and chilled, dizzy and pulsing and empty like a balloon. High overhead, a hawk hangs in the air, frozen in place, as though the fact of atmosphere were only a theory, a lie. 2

An attempt at describing the sky becomes an attempt to register the difficulty of describing the sky. In its search for an appropriate analogy, the narrative voice stutters through a catalog of phenomena ranging from the domestic ("his wife and daughter"), to the mediatic ("the internet"), to the biotechnical ("DDT," with its uneven distribution of harm between the Global North and South), to adumbrations of the book's other protagonist, Cassidy Carter, a former child star and current mid-list actress. What unites these phenomena is not any direct causal relation, but a general sense that they all project a "halfhearted presence," a lingering background hum or "whine" that threatens to creep slowly into the foreground rather than crash into it dramatically. Which is to say, in the passage's own words, these are all "ambient" phenomena. Among other things, this is a vision of climate catastrophe itself as background noise: a series of low-bar sensations that "once heard, can never again be unheard" but whose affective intensity is nonetheless blunted, muted.

This scene is also a phenomenological account of a certain kind of subject — a white, downwardly mobile bourgeois, someone previously shielded from the worst of the disaster — becoming attuned to this noise. This process of attunement to climate's "oscillation between ... phenomenality and ... materiality,"3 to borrow a phrase from Mark Hansen, is notably low-key and non-redemptive. Patrick, Kleeman's hapless protagonist, is not ultimately compelled to give up his relatively comfortable (if also precarious) existence and, say, live among near-extinct animals, as the protagonist of a Lydia Millet novel might, and he is not tormented by visions of his own complicity in the crisis, as is the narrator of a novel like Christine Smallwood's The Life of The Mind. Kleeman's novel fits uneasily into the overlapping canons of climate fiction and apocalyptic fiction.4 If it is a work of climate fiction, it is so only obliquely, through the series of micro-sensations and cognitive dodges that constitute its characters' attempts both to apprehend and to ignore climate catastrophe. And if it is a work of apocalyptic fiction, it is so only in a lite sense, less a tale of a cataclysmic end — Day of the Locust — or of scorched aftermath — Parable of the Sower — than an account of a slow, attritional unraveling. Nor is it exactly what Rithika Ramamurthy terms a "climate anxiety novel," where largely white, professional-class characters worry about climate crisis and "retreat to the cloistered space of the first person."5 Indeed, as the motion of the passage above suggests, crisis in Something New exerts the opposite effect, wrenching narrative perspective away from the locus of the individual subject and toward farther-flung, if hazy, phenomena.

Ecologically oriented literary criticism tends to have an affinity for more spectacular versions of climate's phenomenality, its tendency to crash violently into the foreground of our awareness from the unremarkable background. Amitav Ghosh's much-cited The Great Derangement begins with a catalog of dramatic figure-ground reversals: a pattern on a rug is revealed to be a dog's tail, an ordinary vine becomes a snake, an asteroid an alien monster. What was once inert and invisible "turns out to be vitally, even dangerously alive."6 For Ghosh, the eruption of climate catastrophe is the ultimate reversal of this sort. An aberrant event like a city-devastating tornado reveals "the environment" to be not a static and ignorable abstraction, but an agent endowed with a power equal parts world-making and world-destroying. Much recent ecologically motivated theory has tried to play the role of the catastrophe and effect this clarifying reversal itself, through the dazzling rhetoric of prosopopoeia and litany.7

Ghosh is of course talking about novels. The realist novel, his argument goes, depends on what Franco Moretti calls "the relocation of the unheard-of toward the background ... while the everyday moves into the foreground."8 For Ghosh, this means that the realist novel struggles on a formal level to narrate the "improbable" catastrophic events that climate change precipitates.9 On a warming planet where "hundred-year storms" now happen nearly every year, it is perhaps increasingly hard to see such catastrophes as a forgettable background that evanesces out of sight so that the unaffected may continue their everyday lives. To have any hope of registering such a situation, the realist novel would need to drastically rework the relation it sets up between figure and ground. The background would need to erupt spectacularly into the foreground, finally revealing the violence that both threatens and makes possible the dull thrum of the ordinary. In Hansen's terms, the novel would need to flip the phenomenological switch on ecological crisis from obdurate, ignorable "materiality" to engrossing, spectacular "phenomenality."

And yet over the past two decades or so there has been something of a shift in the way theorists, ecological and otherwise, conceptualize crisis: not just as a sudden and unignorable flashing forth of danger, but also as a kind of attritional "slow violence," to use Rob Nixon's term, or even the crushing dullness of what Lauren Berlant memorably calls our "crisis ordinary."10 These are conceptions of crisis not as spectacular foreground, but as noxious background, weakly tugging at the edges of our attention without ever quite taking center stage in consciousness. Janet Roitman wonders how "crisis, once a signifier for a critical, decisive moment, [came] to be construed as a protracted historical and experiential condition" — a fair assessment of this shift, but with the caveat that the experience "crisis" indexes is often qualitatively vague, low-level, atmospheric.11

Ghosh's fantasied figure-ground reversal — a "Big Reveal," as a band of conspiracy theorists in Something New calls it — does not seem especially well suited to capturing such a texture of experience.12 This is not so much because the big reveal as a device is somehow epistemologically lacking, incapable of disclosing some special facts about the experience of living on a dying planet. It is more that the ways in which these facts come to be lived as matters of concern as a rule do not seem to follow the big reveal's arc of violent revelation and epiphany. Writing about what he saw as an "atmospheric turn" in both aesthetic theory and art, Gernot Böhme argues that thinking about atmosphere as an aesthetic concept ought to "shift[] our attention away from the 'what' something represents, to the 'how' something is present."13 Taking a cue from Böhme, we might say that the big reveal belongs not so much to a genre (the mystery) or even a form (the novel) so much as a particular aesthetic mode, a manner in which things become present: one where phenomena are made present by crashing dramatically into our conscious, thematized awareness. That is, the big reveal belongs to an aesthetic mode where a strict and relatively static figure/ground distinction — as opposed to the continual "oscillation" Hansen attributes to the two terms — is enforced. Call this, to adapt Jennifer Roberts's term, a "punctual" mode, one where significance is concentrated in a few bold figures set against a background of set-dressing.14

This essay reads Something New as both an enactment and a theory of another sensory mode. Following Kleeman's narrator, we can call this an ambient mode: a mode in which significance is dispersed evenly, "everywhere and nowhere at once," and at a low affective intensity, with a feeling of "halfhearted presence." Where ground does not suddenly and dramatically reverse into figure but leaks or shades into it, like fog or like a gathering plume of toxic smoke. Kleeman's novel, this essay contends, is less interested in climate as a thematic problem than it is in representing, investigating, and ultimately historicizing a particular mode of sensing climate crisis. This mode of sensing seems especially well calibrated to intuit the present as an ongoing crisis, a site of slow violence, "a violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales."15 But while Nixon identifies slow violence with the "environmentalism of the poor" and mass movements in the Global South, Something New is resolutely focused on minor disruptions to the smooth functioning of bourgeois life, as well as the vast tissue of gigwork that sustains it, in LA.16 Ambience, Kleeman's novel suggests, is one structure of the feeling of climate crisis breaching this lifeworld — even as this feeling, as we will see, often produces not a form of ecological consciousness but rather a suspended state of vaguely-sensing-but-not-knowing; what Anahid Nersessian calls "nescience."17 To better ground these claims, before returning to Something New and some of its most prominent intertexts, I first sketch a brief genealogy of the concept of ambience as it has been deployed in literary studies and media theory. Positioned in the hazy conceptual territory between media theory and ecocriticism, ambience provides an occasion for a rapprochement between the fields.

Ambience: A genealogy

At the most basic level, ambience names a background, a surround or penumbra that, as Dora Zhang has argued about the related concept atmosphere, is "difficult to pinpoint or localize" but nonetheless palpably present.18 The colloquial usage of ambience as the felt character of a space — often a built or what Böhme calls a "tuned space" — underscores this slippery quality.19 It names an elusive, not-totally-objective but also not-totally-subjective something in the air. Literary studies has periodically reached for ambience and its cognate concepts in its attempts to theorize texts' encompassing emotional textures. Sianne Ngai conceives of "tone" as "a literary text's affective bearing, orientation, or 'set toward' its audience and world."20 To posit and interpret a text's tone, Ngai argues, the critic must "generalize, totalize, and abstract the 'world' of the literary object."21 In general, though, the dominant accent in the field has been on ambience's resistance to interpretation. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht recovers the Heideggerian concept of Stimmung (variously translated as mood, attunement, or even atmosphere) as a cipher for all the somatic immediacy of aesthetic experience that "meaning cannot convey."22 William Empson gets at the specifically sensory dimension of this supposed ineffability with his notion of "Atmosphere," which he defines as "a direct 'physical' quality, something mysteriously intimate... something like a sensation which is not attached to any one of the senses."23

These versions of ambience and its conceptual analogs are ways to think about what phenomenological media theory calls the "hyletic" dimension of aesthetics — that is, the element of aesthetics that concerns the raw impact of the world's materiality on the senses, apparently "prior to any division between mind and matter."24 For media theorists working in the phenomenological tradition, human perception has a "pre-personal" moment; its initial impulse unfolds before any distinction is made between background and foreground, self and world.25 This, as Mark Hansen writes, is "what we might call our originary 'environmental condition': our direct contact with the world that 'precedes' any division of mind and matter and that continues surreptitiously, imperceptibly, to inform 'our' sensory experience, as it were, 'before' it becomes ours."26 Some media "materialize" or confront us with this condition — that is, with the "atmospheric" character of perception — with particular insistence, while others hide it.27

One name for media that try to activate or confront us with this "environmental condition" is ambient media, a big stylistic tent that encompasses background music, audiovisual relaxation aids, and multimedia installation art. These media share a desire to occupy the dim edges of perception, not seizing the beholder's attention so much as softly enveloping it. Designed to be felt while being more or less ignored, ambient media work to set a general, free-floating mood in a space. While such media no doubt have a long history, the first explicitly, self-consciously ambient media object is Brian Eno's 1979 record Ambient 1: Music for Airports, whose liner notes have come to serve as a sort of manifesto for ambient music.28 There, Eno theorizes ambient music as an ambivalent answer to Muzak, the brand name that still stands metonymically for the instrumental "canned music" piped into shopping malls and other semi-public spaces in wealthy consumer nations like the U.S. and Japan. Eno imagines ambient music as an alternative to Muzak's pushy approach to what Paul Roquet calls "atmospheric mood regulation."29 While Muzak moves to flatten out the affective texture of an environment, ambient music is "suited to a wide variety of moods and atmospheres" — that is, it is meant to produce a sense of attunement to the environment as it is, preserving its emotional ground tone rather than altering it.30 And yet even here there is a hint of the regulatory. Regardless of the features of the environment into which it intervenes, ambient music works to "induce calm and a space to think," opening up a hollow or oasis or pod in the middle of an environment.

These, then, are ambience's core contradictions. On the one hand, ambience names a mode of radically extended perception, even a merging of body and environment; on the other, it names a mode of anesthetic, hermetic insulation from one's environment. On the one hand, it promises to disclose a kind of sensory commons, to catch the raw flow of matter before it is reified in consciousness; on the other, it works to carve out a zone of privatized space amid the threatening impersonal swirl of an environment in profound crisis. At this level of abstraction, we can start to see another side of ambience — one so obvious it has perhaps gone without saying in the majority of media-theoretical work, forming the unremarkable background against which all this theorizing is set. In large part because the majority of theorizing about ambience has taken place in media studies, the conclusions theorists have drawn from it tend to be technical in flavor, about the control society, the human-technical interface, and so on. And yet if ambience is at bottom a mode of perception derived from our originary integration with our environment, is it not a crucial mode through which we perceive the degradation of that environment; through which we are made to feel the denaturing force of crises slow and fast on the very air we breathe? And is is not also a mode through which certain of us may seek reprieve from the feelings of panic, grief, and loss that such awareness engenders? Tim Morton proposes that we understand ambience as "a poetic enactment of a state of nondual awareness that collapses the subject-object division, upon which depends the aggressive territorialization that precipitates ecological destruction."31 To use Morton's word, this is an explicitly "warm" and fuzzy vision of ambience, where certain media objects are endowed with the magical power to collapse the "subject-object distinction" and feel themselves as part of "a world without center or edge that includes everything."32 Morton disparages objects like New Age relaxation music as "corrupted materialist forms" of ambience.33 Such a claim conveniently discounts the possibility of a synoptic view of ambience as both aesthetic and anesthetic, both a mode of feeling ecological crisis and of avoiding it. It is this view that the novel bears out, and which will serve as the theoretical orientation for the remainder of this essay.

But what can a novel capture of ambience's pre-personal experiential swirl? After all, as one familiar account goes — one that is hard to dispute — the novel is the paradigmatic literary expression of a certain bourgeois individualism: a vision of a self-contained subject endowed with an infinitely deep, psychologized "interior" neatly sealed off from the outside world. "The epic individual, the hero of the novel," György Lukács famously wrote, "is the product of estrangement from the outside world."34 If ambience is a sensory mode that depends on at least a temporary hiccup in this reifying process of estrangement — a moment of virtual indistinction between subject and world — it would seem that a text seeking to inhabit this mode would need to exit the universe of the novel and become something else entirely. Perhaps, as Morton's account of "ambient poetics" implies but never fully explains, it would become a form of poetry.

Indeed, the most notable recent experiments in something like ambient writing have tended to be poetic, in the loosest sense of the term. Tan Lin, the contemporary writer perhaps most closely associated with the category of ambience, describes his work as an effort to thematize the usually unacknowledged background against which the act of reading takes place — its "overall atmosphere or medium," as he puts it in one interview.35 An ambient aesthetic mode, as he explains, aims to produce a "non-directed" state of consciousness, one not focused on any discrete object but rather on this total atmosphere. Accordingly, Lin's own ambient writing aspires to the status not of singular text but that of microcosm, of a miniature media ecosystem. In texts like HEATH (sometimes styled to include the telling subtitle "plagiarism/outsource") and Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004. The Joy of Cooking, Lin pulls in plagiarized text, PowerPoint slides, Kanban boards, and other extraliterary material into an undifferentiated mediatic soup. Lin's most novelistic text, Insomnia and the Aunt — whose jacket copy announces it as an "ambient novel" — interposes photographs with passages of flat description, mostly of television broadcasts that the main character watches with his aunt in the motel she owns.36 If this is fiction, it is, in Irene Kim's fine phrase, "climate-controlled fiction."37

And yet the question of medium remains. In what meaningful sense can a novel, a form still inextricable from the absorptive technology of the book — whose choreography of attention even Lin's most experimental work still depends on — be a background phenomenon? The simple answer is: it can't be. But I want to suggest that this fundamental formal incompatibility is paradoxically what allows Kleeman to stage such a productive encounter between the ambient mode and the punctual strictures of novelistic form. Arguments like Ghosh's belong to an ecocritical tradition that searches for the literary forms best suited to depicting anthropogenic climate change and its ravages. And yet if climate change is an almost comically large and diffuse object, does it not make more sense to attend to the ways in which texts inevitably fail to depict it in its poisonous totality, to bring their subject into focus as a stable figure?38 In a discussion of certain patterns of academic stumbling, Berlant coined the phrase "genre flailing," which they define as "a mode of crisis management" that involves "throwing language and gesture and policy and interpretations at a thing to make it slow or make it stop."39 Surely the confusion of speculative elements and straining scale shifts that novels often employ in an effort to come to grips with climate catastrophe constitutes one of the most significant types of literary genre flail today. And so, to take one more step: if genre flail is a symptom in the proper Freudian sense of an attempted cure, wouldn't it be more fruitful not to look for and police the accuracy of positive literary representations of climate change, but to attend to the ways in which climate change as an object necessarily scrambles or denatures any literary attempt to represent or avoid representing it? Reading this way, we would look not for how climate appears in literature's space of representation, but for how an encounter with climate formats and constrains that very space. We would pay attention to how climate makes itself felt indexically in fiction, in certain disturbances of form, rather than how it appears as the content of a work of fiction. This is to take the titular "great derangement" not as a state of novelistic climate denial wherein authors disappear climate catastrophe from their books, as Ghosh suggests, but as the derangement of form that climate change necessarily effects.

Something New registers these ambient phenomena primarily in disruptions to their normative functioning: their distribution of significance, their setting of foreground characters against an indiscriminate background, the machinery of their plotting. Something New deploys these failures deliberately, transfiguring them into a central structuring principle. If Lin's work is ambient in form, Kleeman's novel turns out to be ambient through a strategically deployed process of deformation under the pressure of representing constant, low-grade climate emergency.

Loop

What happens to novelistic plot when the future appears less as a repository of infinite possibility and more as a hazy zone of dread? Once it was relatively fashionable for literary critics to celebrate postmodern fiction's dedication to a certain vision of open-endedness. Authors like Morrison, Pynchon, and DeLillo made efforts to trouble teleological understandings of history as an inexorable march toward a set endpoint.40 Or at least as a one-way street. Pynchon's California freeways, studded with ominous industrial skylines and cut-and-paste suburbs, transmuted symbols of postwar U.S. progress into a chronotope of entropy. Following these freeways yields nothing but a lesson in matter's cosmic tendency to drift away from coherence. The elastic LA freeways in Karen Tei Yamashita's Tropic of Orange — which shrink as the world literally gets smaller — materialize the violent forms of space-time contraction unleashed under neoliberal globalization while also manifesting what some might call the upsides of that era's deregulatory, market-expansionist fervor, in the form of a superstructural froth of small-world multiculturalism.41 Call these the emblematic figures of the high-postmodern and late-postmodern modes, respectively, of anti-teleological plotting. The open road is an appropriate chronotope for both: in Pynchon's and Yamashita's hands, it could signal the narrative possibilities available to a novel freed of the burdens of the supposedly end-directed realist plot, in whose ideal type characters are sorted and dealt a fate.

Something New ends, or nearly ends, with two minor characters, Horsehoe and the Arm, driving in a loop around LA's freeways. Afflicted with an acute memory-loss condition ("Random-Onset Acute Dementia," ROAD for short), they decide that making this circuit is the way they want to slip out of conscious life.42 "But why drive in a loop?" asks the Arm. "Because that's our plan," Horshoe replies:

You lose your memory, I lose my memory — the freeway remembers for you, it gives direction. You can look around at everyone else and accelerate to their speed, you don't have to know what you're doing, where you're going ... nobody's ever really been lost on the highway: even if it's not where you want, you're going exactly where the highway intends."43

The road contains no promise of future fullness, even in negative form as total indeterminacy, total freedom in the void. The open road becomes a closed loop, a device for easing the two drivers into the perpetual present they will soon inhabit.

As the two companions drive, sensations begin to lose their outlines and melt into an indiscriminate wash:

As the ocean comes into view once more, the Arm has a sudden revelation: "Are we going in a loop?" he exclaims, sitting forward, intent on the road.

Horseshoe is silent, contemplative. He realizes now that it is the clouds that make it so dark: they cover the sky like a rash, like a burning. He can't tell anymore where the smoke ends and the sky begins, can't see the difference between earth and firmament. If he waits too long, he'll forget the question.

Finally, he admits it: "I don't remember anymore." The turn signal clicks frantically. The horizon line has disappeared. The vanishing point is everywhere. And as night completes its fall, even these distinctions will dissolve into air.44

This passage starts out as a phenomenology of forgetting, but it ends up somewhere darker. As the question of whether they are looping itself loops, "smoke" collapses into "sky," "earth" into "firmament." This collapse may be a product of dementia-related psychosis — a sense of indistinction, all the way down to a fundamental indistinction between the body and its surround, being a signature schizophrenic symptom — but it is also an objective phenomenon happening in the novel's material world. Throughout the novel, LA has been on fire. This fact mostly registers to the characters as a minor inconvenience ("it's not really an emergency," Patrick reassures himself at one point, "if you can drive around it") or a source of creeping low-level dread.45 The more the forgetting disease spreads throughout the population, the worse the fires seem to get. The "horizon line" that has "disappeared" is not just the phenomenological horizon, the orienting anticipation of the future that animates consciousness, but the material horizon, a sky engulfed in suffocating smoke. "The vanishing point is everywhere": the distinction between foreground and background goes up in smoke, both in consciousness and in the world, or what's left of it. At the same time, there is something banal about this process of disappearance. The vanishing point is everywhere, and so it is thoroughly unremarkable.

A loop that disintegrates in the end — recalling William Basinski's influential ambient musical composition The Disintegration Loops — both registers the low-grade, ambient horror of a slowly burning world and offers a weak antidote to that horror, a warm bath of forgetting. This is a decidedly different chronotope from the postmodern open road. The indeterminacy that was so subversive in Pynchon and so generative in Yamashita has frayed into a dull, dual sense of, on the one hand, a looping endlessness, and on the other, the creeping certainty that something significant is coming to an end. This temporal stuckness forms the mostly unacknowledged emotional ground tone of the most recent wave of critical commentary on the apparent vanishing of plot from literary fiction. No doubt such a vanishing has a long and, well, storied literary history. As Clare Sestanovich, Megan Marz, and others have noted, literary-world alarm bells have sounded over the supposed "death of plot" at least since the heady early days of modernism.46 Writing in a moment between that originary one and our own, Leo Bersani describes the apparent plotlessness in authors like Robbe-Grillet and Pynchon as a function of a relentlessly flat distribution of "significance."47 Whereas in the paradigmatic realist novel, "at certain moments in the story, the narrative engine puffs a little more strenuously than at other moments, and the rest of the time we can, as it were, glide along on the extra steam," in these experimental works, there is no "governing pattern of significance" but an even, general "diffusion of meaning" where every moment is just as meaningful — or meaningless — as the next.48 Which is to say that at the level of narrative, too, the distinction between foreground and background collapses, swallowed by a "diffusion" of "steam" that prefigures Kleeman's all-engulfing smoke cloud.

The most recent wave of apparent plot-erosion is not just a literary affair. In a series of essays for The New Yorker, Kyle Chayka makes the case that in a meaningful sense, the contemporary media environment, from the endless scroll of the TikTok feed to the aimless drift of much made-for-streaming television, has come to privilege atmosphere over plot — "vibes" over story, the benign wash of "ambient television" over the novelistic vision of prestige TV. 49 Others have gone so far as to identify the disappearance of plot as something like an emergent structure of feeling, as much a feature of the political landscape (in the U.S. in particular) as a quality of our expressive media. In a recent forum on the state of contemporary fiction, Clare Sestanovich identifies a looping open-ended dread as a general hovering mood:

On the one hand, we circulate in a so-called public square where conspiracy theories flourish and bad actors reign — that is, we seem to live amid a glut of plots, with an insatiable appetite for more. ... And yet we have also developed a remarkable tolerance for narratives with unpredictable, unsatisfying arcs, the sort that, at least in theory, encourage nuance. News stories are constantly breaking, rarely repairing. The reports reach no clear conclusions; your news feed seems, actually, more like a loop. ... The pandemic, meanwhile, is a story with no end in sight ... When we live in a perpetual suspension of disbelief, with such a meager promise of narrative closure, it seems reasonable to wonder if the goalposts of good storytelling have moved.50

Embedded in this brisk inventory is a compelling suggestion that the loop, an aesthetic form that is recursive and self-enclosed but that never quite offers "closure," may be especially suited to a historical moment characterized by permanent, background emergency. As the smoke closes in, maybe looping, low-intensity background sensations are both the chief way in which the danger manifests itself and a weak saving power to insulate against the danger.51

Kleeman's novel is legible as both an instance of and an allegory for this vaporization of plot. But even more crucially, it forges an imaginative link between the erosion of plot and a certain waning of the affective pull of the category of "the future" in the face of accelerating anthropogenic climate change. When "the vanishing point is everywhere," plot loses its foundational ability to distinguish between significant and insignificant events. It also loses its sense of an ending, an ultimate horizon in the distance toward which these events lurch. What Something New Under the Sun gives us is a novelistic mode in which the end is already here, everywhere, humming along in the background, diffusing across consciousness like smoke. Frank Kermode writes that although "the End has perhaps lost its naïve imminence, its shadow still lies on the crises of our fictions; we may speak of it as immanent."52 We might say that Something New collapses these two senses: in its world, the end is both imminent, in fact already here, and immanent, saturating every facet of earthly life.

In this way Something New takes DeLillo as its closest model. White Noise is a constant faint background presence, with its ominous "airborne toxic event" and its muted down-spiraling trajectory from aimless domesticity to noir intrigue.53 The airborne toxic event has a curious phenomenological structure: it toggles between an event — with all the spectacular punctuality the term implies — and something like a general condition, a denaturing background force that inflects or tints all other phenomena, down to the unsettlingly vivid sunset that closes the novel. And yet the simple act of naming affords the airborne toxic event a certain punctuality. Kleeman's lite apocalypse is nameless: it is no one thing, not even a thing at all. This is both a riff off DeLillo and an intensification — which is to say a weakening — of the ambient emergency at the heart of White Noise.

If plot distends and threatens to aerosolize in its effort to get a handle on ambient phenomena, registering a burning world where everything paradoxically appears "frozen in place," conditions do not seem especially fertile for plot. From the outset, Something New allegorizes a tension between plot's end-directed motion and ambience's looping stasis. Much of this allegory is placed in the mouths of Horseshoe and the Arm, the two young film P.A.s who eventually lose their memory on the freeway loop. In pseudo-MFA babble that, once again, recalls the speech of a certain DeLillo theorist-clown character archetype, the Arm makes an impassioned case for not skipping a few seconds ahead on an internet video:

But think about how much of the story we'll lose ... if we rush it. The ambient time, boredom, irritation, atmosphere. The texture. The suspense. A long stasis that, like winter blossoming into spring, reveals surprises within. What this sort of footage lacks in plot structure, it gains back in the quiet sorcery of something happening out of nothing .54

It is a funny joke — the video in question is a clip of movie star Cassidy Carter beating back a creepy paparazzo; there is no "story" to be found, or maybe the only story it contains is one of violence — that outlines a familiar vision of ambience as experiential "texture," the hyletic dimension of aesthetic experience that hits the body before being translated into discrete sensations and judgments. There are no doubt analogies to be drawn between this ambience/plot dialectic and the dialectic Fredric Jameson proposes between "story" and "affect" in his late masterwork The Antinomies of Realism. For Jameson, literary realism is caught between an orientation toward "destiny," whose chief manifestation is story, and one toward "the eternal present," whose chief manifestation is affect, or pure sensation.55 Much more could be said about this, but for now it is enough to point out that Arm gets at something similar with his accidentally insightful theory of "ambient time": an eternal present that, instead of perpetually, amnesically renewing itself, stretches on interminably and makes you wonder if skipping ahead to the end, the final and unambiguous end, might be a welcome change.56 Significantly, this theory of ambient time emerges from an engagement with streaming media — whose ability to deliver an apparently undifferentiated flow of soothing background sensation, as we've seen, has enabled the rise of new ambient video genres.

Pod

This hint at a vision of ambience as salutary, even therapeutic, forms a steady undercurrent throughout Something New. To grasp this dimension of the novel's engagement with ambience, it helps to take a detour through another of its multimedia intertexts. Todd Haynes's 1995 film Safe is also structured like a loop — or, as a minor character phrases it at one point, a "spiraling down."57 A familiar set of factors coalesces some twelve minutes in: Southern California, driving, dark smoke. Homemaker Carol White, played with wispy reticence by Julianne Moore, pulls off the road to escape a thick, choking cloud of exhaust. As she drives down the spiral ramp to an underground parking garage, her increasingly violent coughs swallow the sounds of the radio.58 Low, mechanical groans seem to spill from the film's sonic background into the foreground as a series of shot/reverse-shot pairs jerk between the careening road ahead and Moore's panic-stricken face, which throughout the film the camera largely takes great pains to keep in an abstracted middle distance, rarely getting too close. From this moment of spiraling catabasis onward, background bleeds into foreground, at the levels of plot and style. Background noise gnaws at the edges of foregrounded dialogue; shots melt into one another; sensations start to lose their borders. Meanwhile, what were once unremarkable, and therefore unnoticed, features of Carol's upper-class white American lifeworld — hair products, designer couches, processed foods — begin to trigger increasingly serious allergic reactions. If an environment is phenomenologically what we forget engulfs us, Carol's condition registers as a kind of environmental loss, a peeling away of her unacknowledged surround.

Heather Houser identifies Safe as a work of what she calls "ecosickness fiction," a narrative that labors to "join experiences of ecological and somatic damage through narrative affect" — in this case, the damage in question being that wrought by Carol's "chemical ambience."59 We could go further and say that Carol's condition is itself a mutated form of ambience in the sense this essay has been trying to develop, with the aid of Hansen and other phenomenological media theorists: a painful openness or attunement to the low-level but cumulatively violent pre-personal microsensations that the body's originary integration with its environment produces. Indeed, an Eno song serves as a soundtrack for Carol's restless nighttime wanderings through her house's nonspace, the moaning washes of synth giving some objective aesthetic form to the free-floating dread that now inheres there.

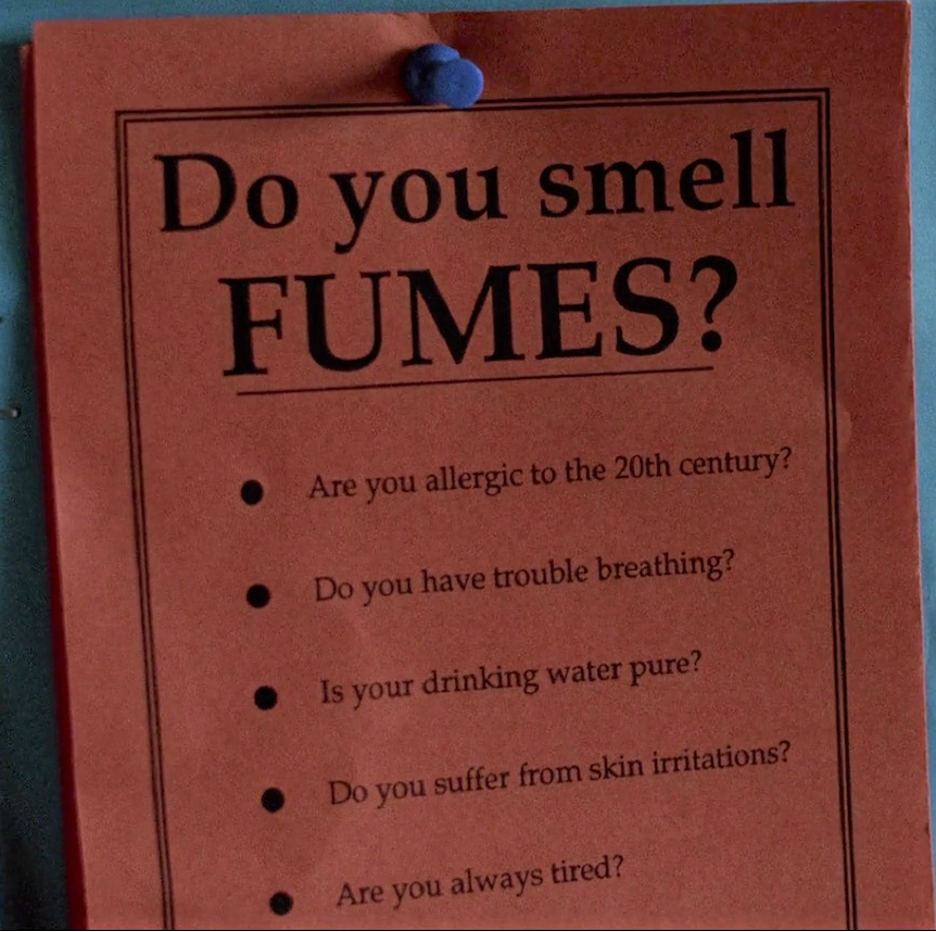

But could ambience also be the cure? Through a poster at her health club ("Are you allergic to the 20th century?"), Carol finds a support group for people with "environmental illness." The official language of the group draws heavily from the backwash of 1960s human-potential mysticism, which by the late 1980s, when the film is set, had largely curdled into the idiom of yuppie self-help. In an echo of Scientologist cosmology, the leader of the group emphasizes the importance of "clearing" one's illness. "The first thing you need to clear," she says, "is an oasis." By this, she means a sealed-off zone, far from all the offending sensations. Somewhere even more hermetic and podlike than the bourgeois home, which forms the setting for the first portion of the film, framed in an uncanny doll's-house perspective.60 Which is to say: a space of forgetting to counteract the painful hyperawareness that constitutes Carol's condition (likely MCS, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity). While Houser maintains that ecosickness narratives "bring readers [and viewers] to environmental consciousness," Safe is much more a story of environmental unconsciousness, or at least of one woman's quest for it.61 In interviews, Haynes has articulated the film's central concerns in similar terms: "What is immunity, really? In a weird way, it's something that we covet, but it's also something that's in some ways about an unconsciousness; it's about being away."62

This "away" is instantiated in Wrenwood, the New-Agey treatment center where Carol ends up staying. There, she is bombarded with individualist slogans. On non-directed or outward-directed feelings of rage and powerlessness, the prescription is to "focus these feelings inward," toward "self-realization." At Wrenwood, self-realization means accepting the frankly shocking maxim that "the only person that could make you sick is you."63 Despite its ramshackle appearance, Wrenwood aspires to be the ultimate climate-controlled "tuned space," a contained atmosphere calibrated to allow, or force, patients to take responsibility for their illness. Given not treatment so much as space to figure things out on their own, Wrenwood's patients are encouraged to turn to "ambience as a central technique of self-creation and self-maintenance," to use Paul Roquet's phrase.64 As Roquet argues, in "the neoliberal phase in a shifting relationship between the self and the surrounding air," the individual assumes all risk and all responsibility for damage that is fundamentally structural, impersonal, atmospheric.65 When the supports for life are stripped away or enclosed and sold off, "the self, now tasked more than ever with creating a life from scratch, need[s] an ambience appearing to hand the techniques of atmospheric mood regulation over to the individual, to use as they [see] fit."66

Safe closes with a sickly Carol moving into a podlike dwelling at the far edge of Wrenwood. The camera occupies the place of the mirror, the pod's only real amenity, and we see Moore's face close up for the first time since the parking garage spiral. "I love you," she says to herself, but also to us, in her nearly weightless voice: "I really love you." This is the ironic end point of ambience, which as we know names a mode of extended sensation to background phenomena often accompanied by a slackening of a sense of the self-world boundary, when it becomes a technique for individual management of the surrounding air and the affects it seems to carry: total isolation, total airlessness. And yet it is a soothing airlessness. There is also something protective, almost amniotic, about the looping stasis of "ambient time." Haynes calls the scene an "inverted birth, sort of like going back into a womb" — the ultimate closed loop.67

Something New has its own Wrenwood: a "nature retreat" that goes by the similarly spondaic compound name "Earthbridge." While author Patrick is out in Hollywood gofering and chauffeuring, his wife and daughter move to Earthbridge for what turns out to be an indefinite retreat. Alison sees the retreat as a way to work through her consuming climate grief. She tells Patrick:

"I look out the back window of our house and I don't see the park or the trees. I see all of it dying. Part of me knows it's not — 'dying' is the wrong word for it — but another part can look out and see a place that's already dead. You see? I look at Nora and I know there's no future for her, and it tears my heart in two."68

This is to say that Alison perceives a kind of "halfhearted presence" in the natural world around her. Hers is a special attunement to the "depresencing of the world," a low-grade, ambient sense of extinction unfolding around her. Like Carol's condition, this ambient awareness is the result of an accumulation of low-grade sensations: "As with most catastrophes, she knew it hadn't happened all at once.... You couldn't say when it began, only that at one point it was certain to unfold."69 And like "environmental illness," this environmental grief constitutes a gradual, nonspectacular shading of background into foreground, in this case explicitly inflected with a sense of futurelessness. In a meaningful sense, Alison simply is Carol.

With "no future" on the horizon, Alison retreats to Earthbridge to develop her attunement further and to learn how to grieve better. What she finds there is less a treatment center than a sort of eco-commune, with work rotations and daily grieving sessions for recently extinct species. And yet like Wrenwood, Earthbridge, filled mostly with professional-managerial liberals wracked with guilt over their wasteful lifestyle, turns out to offer only a form of containment of or isolation from the ongoing crisis it claims to oppose. Reflecting on the official Earthbridge mantra — "I want to live in the world, not upon it. I want to live in reciprocity, not exchange. I want to give without keeping a ledger. I want to love the earth like I love the person I love the most..." — Alison wonders whether the "real role" of rituals like these is "not to pay tribute to all this planetary loss, but to sort and codify it, keeping it contained within a series of habits, sayings, rituals. To keep the end within sight, but make it feel livable."70 Despite its intentions to sharpen and deepen its participants' consciousness of climate catastrophe, Earthbridge turns out to be a sort of unconsciousness-producing machine after all. The carefully cultivated "clear" atmosphere at Earthbridge, with its looping habits, turns out to be a "technique of self-creation and self-maintenance," a reparative fix to make life "livable" amid ambient crisis.

Slow dissolve

Safe ends inside this containment pod — and White Noise, for its part, leaves us with the sealed pod of the bourgeois family, however ironically. Something New tries to probe the crisis outside. In its quest to give a form to this crisis, the novel tries out a series of generic modes and attendant plot conventions. As Matthew Schneier describes it, Kleeman's novel is "an unlikely amalgam of climate horror story, movie-industry satire and made-for-TV mystery."71 This is to say that the novel is something of a genre flail, which in Berlant's formulation is a particular "mode of crisis management." The motivating question behind this flailing is the question of crisis itself — or, as Schneier phrases it, "what constitutes an emergency?"72 Each genre the novel turns to presents a different, largely unsatisfying answer. Starting off in the world of "movie-industry satire," filled with low-level gofers who vomit up high-theory word salad and rich execs on the hunt for "sequel potential," emergency is mostly a topic for abstract contemplation.73 Pondering the problems of self-driving cars, the Arm muses: "When change happens, we want it to happen all at once. In transit, there's catastrophe." Horseshoe's somehow more ponderous reply: "Catastrophe is incomplete change. ... Change is violent for those who arrive to it late. ... The safest thing would be to remain perfectly still... and let the future simply arrive."74 This masterclass in bong-rip theorizing produces something like a governing maxim for techno-futurism: it is not history, with its irreducible twinge of political side-taking but, change — a metaphysical, depoliticized category — that hurts. And in a homeopathic way, at that; the pain of change is always the birthing pain of something new and better. Catastrophe is ultimately salutary and unavoidable — a view that it is easy enough for one to maintain, and easy enough for the novel in its parodic mode to play off as a joke, as long as the "small plumes of smoke in the distance" stay in the distance, "on the occluded face of the yellowing foothills."75

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, Hollywood excess begins to shade into noir mystery. The emergency at the heart of the novel begins to take the shape of a conspiracy. Its outlines are hazy to say the least, but it seems to involve a couple of film producers, the manufacturer of a water substitute ("WAT-R") that has proliferated in the wake of devastating drought in California, and a chain of mysterious "memory clinics" for dementia patients. Patrick is seized with an urge to investigate, and he conscripts Cassie, who is now starring in the loose film adaptation of his novel, to help. As the unlikely pair cases the Pynchonian freewayscape for clues, they begin to suspect there is one detail, one connection, that will finally illuminate everything. Patrick has perhaps gotten this conviction from the internet. He stumbles on a message board dedicated to Kassi Keene: Kid Detective, the TV show Cassie starred in as a child. One faction on this message board calls themselves "Revelators." The Revelators are devoted to close-reading old episodes for adumbrations of an event they call "TBR — The Big Reveal, a plot twist they believe had been planned for the canceled sixth season, a narrative mega-event that would have cast all of Kassi's investigations in a newer, darker, more unified light and pointed the way to a mega-crime that exerts its lingering influence."76 A hardcore sub-faction of Revelators believe in "TBR IRL," the idea that the show is an elaborate allegory for a "major crime that the government was covering up."77 And yet predictably, despite all the investigating, no Big Reveal is forthcoming in the novel's diegetic IRL. The clues point not to a bottomless conspiracy like Pynchon's Trystero, but to banal grift: a pair of film producers have cornered the market on WAT-R, are raising funds, The Producers style, for a film they do not intend to make, and are planning on absconding to an "off-grid bunker" in New Zealand and sealing themselves off from a burning world.78 It turns out WAT-R likely causes ROAD, the acute dementia sweeping across California. The producers do not care. A confrontation with the conspirators dissipates into mumbling incoherence when Patrick suffers an especially severe attack of dementia.

This is a trajectory not toward resolution, but, as Schneier correctly identifies, toward "dissolution."79 And yet this dissolving plot is not, as he goes on to argue, a simple case of Kleeman "seem[ing] to lose interest in the mystery scheme by the end."80 Rather, the novel dramatizes the dissolution of its own plot, indeed of plot itself — even of the punctual aesthetic mode wholesale — as the infrastructures that support human life themselves dissolve. Its form is the unraveling or aerosolizing of its own form. Again, the novel's dorm-room Rosencrantz and Guildenstern lay out the allegorical template for this move:

"I wrote a script in college about an alien invasion," the Arm says. "Small crablike creatures attach to the neural centers of cheerleaders. It begins as a slasher flick — people die in creative and ironic ways — but when the takeover is complete, it becomes a quiet, peaceful sort of thing. Then it's a movie for the aliens, full of colors, lights, moving shapes, and warm, buzzing sounds. But as long as a single human being is alive, its genre is horror."81

This is to say: the Arm's film becomes ambient, diffuses into "warm," depersonalized sensation, after humanity has quit the scene. It is less genre flail than genre evaporation, horror's tight plotting giving way to ambience's directionless haze.

As with so many elements of Something New, this is both a joke and something like a key to understanding the novel's formal ambitions. The novel itself follows a strikingly similar arc to the Arm's admittedly "bad," never-made film.82 Pomo mass-media satire transforms into a detective plot, which in turn dissolves in a vapor of mass forgetting. This progressive dissolution is legible as a quest to find a suitable aesthetic mode for expressing the emergency at the heart of the novel. (Perhaps coincidentally, it is also a neat allegory for a certain literary-historical narrative about the supposed supersession of a hegemonic high postmodernism with the so-called "genre turn.")83 The novel's Hollywood-satire and mystery plots both render this emergency as a discrete, bounded phenomenon: respectively, as something to contemplate in the abstract distance, and as a grand conspiracy to be uncovered in a Big Reveal. Both of these plots depend on a neat division between foreground and background, even as the novel's would-be detectives struggle to bring the occluded conspiracy into the spectacular light of revelation. It is only when the detective plot exhausts itself that the novel finds a mode for capturing the "halfhearted presence" of its organizing crisis.

Like the Arm's film, Something New itself dissolves into an ambient swirl of sensations. Background diffuses into foreground rather than erupting spectacularly into it. As in Safe, the slow erosion of this distinction often registers less as a blissful immersion in warm environmental feelings and more as a sense of supreme alienation. On a last desperate trip out to the desert, motivated by a vague jumble of half-reasons, a seriously debilitated Patrick feels "in the world but separated from it," seized by a sense of "inverse déjà vu" where each moment feels as if it could be "the last in its series."84 Cassie, we learn, feels similarly, "almost as if the umbilical cord that bound her to her surroundings had been cut ... the world had ended, and still she hung around."85 The affective texture of these experiences of worldlessness is curiously smooth and low-intensity: there is "an empty space where hope should be. An empty space where fear should be. And so the feelings of hope and fear drift through that space like clouds in the sky, filling your with temporary hope, temporary fear. This moment is like that one. Her fate decided but unknown."86 In other words, these are ambient sensations, slices of low-bar, pre-personal experience. Ambience's ability to function as an aesthetic pod, sealing us off from the world outside by offering a phantasmatic substitute for it, meets its dark inverse here: ambient sensations as signs of the world's — in its phenomenological sense, which is inextricable from its material sense — slow vanishing.

As the characters begin to disappear, whether in the desert or on the smoke-choked freeway, chunks of speculative, eons-spanning narration intrude. By the end, they comprise the whole of the narrative. The novel's final passage loops back across geologic time:

In the long before, there were rivers that tumbled from the mountain chill into the sweet-smelling flatlands. The water ran cool in the heat of the summer and you could see stones at the river floor, gray-brown and russet, clear and close as if they were laid in the palm of your hand. Where night met morning, the mountain lion would slake its thirst as the deer bent to drink, the same river cupped in the bodies of predator and prey. You could wade shin-deep into the running and gaze down at your own two feet, pale as cave fishes in the morning bright. In the cold, every muscle of the foot felt as if it was outlined in pure, sweet light, the pain like the ache of too much running, too much life. With your eyes closed, you stood there growing colder, growing numb, until the cold was gone and your body was absent too, the feeling of nothing, the feeling of movement, the feeling of being river, of keeping the cycle, of rushing downstream to the open sea.87

A near-lyric "you" emerges in this narration of "the long before." On its face, this is a Romantic paean to despoiled Nature, especially to the water that has vanished from the novel's California — a sort of rewrite of the final paragraph of Cormac McCarthy's The Road, with its invocation of a lost place and time where "all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery."88 But as with the "vanishing point is everywhere" scene that precedes this passage, something more layered and sinister is at work here. Since the onset of his dementia, Patrick has been struck by underwater visions, presumably an effect of his body's need for real water. This final scene follows a similar choreography to these hallucinations: the sense of indistinction, of simultaneous expanded sensation ("the feeling of being river") and anesthetic unfeeling ("the feeling of nothing"), the looping time ("keeping the cycle"). There is a strong sense here that "you" in this speculative scene might not some prehistoric person or spirit-being, but rather a dementia patient. It seems this vision is not—or not just—a primordial memory of "the long before," a loop back to the beginning, but in fact a product of a progressive, chemically enforced forgetting.

In an influential short 1935 essay, French writer Roger Caillois coined the term "legendary psychasthenia" to describe such experiences of radical indistinction.89 Caillois proposes that under certain circumstances, schizophrenia chief among them, the human psyche can experience a slackening of its borders analogous to animals' camouflaging techniques. For those who experience this "depersonalization by assimilation to space":

Space pursues them, encircles them, digests them in a gigantic phagocytosis. It ends by replacing them. Then the body separates itself from thought, the individual breaks the boundary of his skin and occupies the other side of his senses. He tries to look at himself from any point whatever in space. He feels himself becoming space, dark space where things cannot be put. He is similar, not similar to something, but just similar. ... The emphasis is surely placed on the pantheistic and even overwhelming aspect of this descent into hell, but this in no way lessens its appearance here as a form of the process of the generalisation of space at the expense of the individual, unless one were to employ a psychoanalytic vocabulary and speak of reintegration with original insensibility and prenatal unconsciousness: a contradiction in terms.90

No doubt many of the ambient phenomena registered in Something New share this structure. (And Safe too, for that matter, with its catabastic descent into the spiraling hell of environmental indistinction.) The simultaneous becoming-river and becoming-nothing of the lyric "you" seem to constitute a textbook case of depersonalization by assimilation to space. But if we understand such depersonalization as a quality of ambient phenomena, we can see that what Caillois identifies as an unviable "contradiction in terms" — between the individual-eliminating impulse to dissolve into the environment and individual-preserving impulse to seal oneself in an oedipal pod — is exactly the dialectic of ambience. The second-person address in Something New's final passage is lyric, but it also contains more than a hint of that quintessential ambient media genre, the relaxation or meditation instructional. Is this the ultimate expression of the dissolution of the world as a viable material and phenomenological support, or a compensatory aesthetic fix, a surrogate sense of world to replace the primary, material one that's on fire? In other words: is this an apocalyptic vision, or a visioning exercise? Ambience's self-dissolving and self-preserving impulses, which is also to say its crisis-registering and crisis-compensating impulses, are inextricable.

This contradiction is exactly what ultimately makes ambience such an effective, perhaps even necessary aesthetic mode for both registering and forgetting the slow apocalypse coming for us all — though undoubtedly for the groups capital has deemed to be surplus populations first. In this way, the ambient mode is perhaps still a privileged mode of perception, one with a pronounced class character. The pod of the supposed self-contained bourgeois subject, or something like it, returns after all, suggesting a further suppressed structural sympathy between ambient media and the novel. Perhaps this pod is merely buffeted by the occasional plume of smoke. Perhaps the sense of encroaching background requires a sense of a stable, if threatened, foreground — property, wages, whiteness — to make phenomenological sense. For those within the pod, it is still possible to view climate catastrophe as something "as ignorable as it is interesting," in Eno's words.91 For many of those outside, there is only the fire.

Mitch Therieau is a writer and literature scholar living in California.

Banner image by Jesus Curiel on Unsplash

References

The writing of this article was supported in part by a Dissertation Prize Fellowship at the Stanford Humanities Center.

- Alexandra Kleeman, Something New Under the Sun (Hogarth Books, 2021), 16. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 19. [⤒]

- Mark B.N. Hansen, "Media Theory," Theory, Culture & Society 23, no. 2-3 (2006): 297. [⤒]

- Here I am thinking especially of Millet's How the Dead Dream and Smallwood's The Life of the Mind. I invoke these authors and texts to show, on the one hand, a tendency in recent fiction for climate crisis to figure as a nagging intrusion or disruption—but on the other, for this intrusion to become all-engrossing, calling forth one's full attention and posing ethical demands. The ambient mode I theorize here does not activate the ethical imagination, or at least not in the same way. As we will see, its demands are transposed more to the register of self-care: keeping out bad input, calibrating one's personal atmosphere. [⤒]

- Rithika Ramamurthy, "Personal Hell," The Drift, May 4, 2021. [⤒]

- Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, The Randy L. and Melvin R. Berlin Family Lectures (The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 3. [⤒]

- Think, to take just one example, of what Ian Bogost calls the "Latour Litany," the sprawling lists of playfully juxtaposed types of objects that feature prominently in Bruno Latour's writing, as well as that of many speculative realist and new materialist thinkers. See Ian Bogost, "Latour Litanizer," Bogost.Com, December 16, 2009. [⤒]

- Franco Moretti, The Novel, Volume 1 (Princeton University Press, 2007), 372, cited in Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 17. [⤒]

- Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 16. [⤒]

- Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2011); Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Duke University Press, 2011), 9. [⤒]

- Janet L. Roitman, Anti-Crisis (Duke University Press, 2014), 2. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 156. One might also wonder, along with Ursula K. Heise and others, about the privileged place of the realist novel in Ghosh's account and the way speculative fiction is unaccountably dismissed along the way. See Ursula K. Heise, "Climate Stories: Review of Amitav Ghosh's The Great Derangement," Boundary 2, February 19, 2018. [⤒]

- Gernot Böhme, The Aesthetics of Atmospheres, ed. Jean-Paul Thibaud (Routledge, 2016), 26. [⤒]

- See Jennifer L. Roberts, Mirror-Travels: Robert Smithson and History (Yale University Press, 2004). [⤒]

- Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2011), 2. [⤒]

- For more on ambient media's relation to economic precarity, see Mitch Therieau, "The Novel of Vibes," Post 45 Contemporaries, March 15, 2022; Mitch Therieau, "Pod-Products for Pod-People," The Baffler, April 2, 2020. [⤒]

- Anahid Nersessian, The Calamity Form: On Poetry and Social Life (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 3. [⤒]

- Dora Zhang, "Notes on Atmosphere," Qui Parle 27, no. 1 (2018): 122. [⤒]

- Böhme, The Aesthetics of Atmospheres, 2. [⤒]

- Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2005), 43. [⤒]

- Ngai, Ugly Feelings, 43. [⤒]

- See Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey (Stanford University Press, 2004). [⤒]

- William Empson, Seven Types of Ambiguity (Chatto and Windus, 1953), 16. [⤒]

- Mark B.N. Hansen, "Ubiquitous Sensation: Toward an Atmospheric, Collective, and Microtemporal Model of Media," in Throughout: Art and Culture Emerging with Ubiquitous Computing, ed. Ulrik Ekman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013): 83. Notably, affect theory independently developed its own notion of atmosphere. See Brian Massumi's conception of "ambient fear" in Politics of Everyday Fear (Minneapolis: Univ of Minnesota Press, 1993). [⤒]

- Shane Denson, Post-Cinematic Bodies (meson press, 2023), 111. [⤒]

- Denson, Post-Cinematic Bodies, 84. [⤒]

- Denson, Post-Cinematic Bodies, 73. [⤒]

- Paul Roquet, Ambient Media: Japanese Atmospheres of Self (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 4. [⤒]

- Roquet, Ambient Media, 4. [⤒]

- Brian Eno, Ambient 1: Music for Airports (PVC, 1978). [⤒]

- Timothy Morton, "Why Ambient Poetics?," The Wordsworth Circle 33, no. 1 (2002): 52. [⤒]

- Morton, "Why Ambient Poetics?," 52. [⤒]

- Morton, "Why Ambient Poetics?," 52. [⤒]

- György Lukács, The Theory of the Novel; a Historico-Philosophical Essay on the Forms of Great Epic Literature (M.I.T. Press, 1971), 66. [⤒]

- "A Book Is Technology: An Interview with Tan Lin," Rhizome, October 24, 2012. I was first introduced to Lin's work by Emily Wang's brilliant conference presentation, "'Minor Conveniences or Intractable Objects': Insomnia and the Aunts," at the 2019 Berkeley-Stanford English Graduate Student Conference. [⤒]

- Tan Lin, Insomnia and the Aunt. (Kenning Editions, 2011). [⤒]

- Irene Kim, "On Ambience, Tan Lin, and American Minimalism," Post45 (2023). [⤒]

- For two (very different) perspectives on climate and the comically large, see Mark McGurl, "The Posthuman Comedy," Critical Inquiry 38, no. 3 (2012): 533-53; and Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (University of Minnesota Press, 2013). [⤒]

- Lauren Berlant, "Genre Flailing," Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1, no. 2 ( 2018): 157. [⤒]

- See, for example, Samuel S. Cohen, After the End of History: American Fiction in the 1990s (University of Iowa Press, 2009); Phillip E. Wegner, Life between Two Deaths, 1989-2001: U.S. Culture in the Long Nineties (Duke University Press, 2009). [⤒]

- See Rachel Adams, "The Ends of America, the Ends of Postmodernism," Twentieth Century Literature 53, no. 3 (2007): 248-72. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New Under the Sun, 212. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 329. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 331-32. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 105. [⤒]

- See Clare Sestanovich, "'Nothing Happens,'" The Drift, June 14, 2022; Megan Marz, "Tale Spin," Real Life, March 14, 2022. [⤒]

- Leo Bersani, A Future for Astyanax: Character and Desire in Literature (Little, Brown, 1976), 52. [⤒]

- Bersani, A Future for Astyanax, 52. [⤒]

- See Kyle Chayka, "'Emily in Paris' and the Rise of Ambient TV," The New Yorker, November 16, 2020; Kyle Chayka, "TikTok and the Vibes Revival," The New Yorker, April 26, 2021. [⤒]

- Sestanovich, "'Nothing Happens.'" [⤒]

- For another account of the loop as a chronotope mediating feelings of futurelessness, see Olivia Stowell, "The Time Warp, Again?," Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022. [⤒]

- Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending-Studies in the Theory of Fiction (Oxford University Press, 1967), 6. Quoted in Dan Sinykin, American Literature and the Long Downturn: Neoliberal Apocalypse (Oxford University Press, 2020), 15. [⤒]

- Don DeLillo, White Noise (Penguin Books, 1986), 117. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 5. [⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, The Antinomies of Realism (Verso, 2013), 26. Jameson's theory of this perpetual present as a "reduction to the body," whereby "the isolated body begins to know more global waves of generalized sensations, and it is these which, for want of a better word, I will here call affect," helps us situate ambience in a thicker knot of theoretical concepts, though untangling this knot would take this essay too far afield. [⤒]

- Horseshoe's counterargument that "avoiding loss is impossible in a world that struggles to conjure even the basic sense of presence" is both inane and undoubtedly Hansenesque, with its framing of ambience as a mode of apprehending the "depresencing of the world." Either way, he wins the argument, and "the video is dragged ahead an inch or so". See Hansen, "Ubiquitious Sensation," 83. [⤒]

- Safe, directed by Todd Haynes (1995; Criterion Collection, 2014), DVD. [⤒]

- Safe, like White Noise, belongs to a late-twentieth-century media regime. Like DeLillo's novel, it is saturated with broadcast media, with radio and TV constantly buzzing in the background. Both Haynes and DeLillo thematize broadcast media's latent ambience; their ability to travel through and inhere in the air. [⤒]

- Heather Houser, Ecosickness in Contemporary U.S. Fiction: Environment and Affect (Columbia University Press, 2014), 2. [⤒]

- My thanks to Allison Saft for this observation. [⤒]

- Houser, Ecosickness in Contemporary U.S. Fiction, 3. [⤒]

- "Todd Haynes and Julianne Moore on Safe," December 12, 2014, by Criterion, YouTube. [⤒]

- Haynes, Safe. [⤒]

- Roquet, Ambient Media, 5. [⤒]

- Roquet, Ambient Media, 5. [⤒]

- Roquet, Ambient Media, 5. [⤒]

- "Todd Haynes and Julianne Moore on Safe" [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 26. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 147. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 292. Compare with the Wrenwood mantra: "We are one with the power that created us. We are safe, and all is well in our world." [⤒]

- Matthew Schneier, "'Something New Under the Sun': A Climate Nightmare in a Burning Los Angeles," The New York Times, August 3, 2021. [⤒]

- Schneier, "Something New." [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 34. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 17. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 17. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 156. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 228. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 337. [⤒]

- Schneier, "Something New." [⤒]

- Schneier, "Something New." [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 17. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 17. [⤒]

- For the argument that placed the "genre turn" at the center of contemporary literary studies' critical lexicon, see Andrew Hoberek, "Cormac McCarthy and the Aesthetics of Exhaustion," American Literary History 23, no. 3 (2011): 483-99. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 280, 296. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 345. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 345. [⤒]

- Kleeman, Something New, 350-51. [⤒]

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road (Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 241. [⤒]

- Roger Caillois, "Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia," trans. John Shepley, October 31 (1984): 30. [⤒]

- Caillois, "Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia," 31. [⤒]

- Eno, Ambient 1. [⤒]