Minimalisms Now: Race, Affect, Aesthetics

What is the minimum volume (and quality) of material or statistical quantity of words necessary to induce a rehearsal of the generic exercise we might term "reading" or an aesthetic encounter we might term "interesting," or at least interesting enough to continue?1 In a 2010 interview, Tan Lin describes his work as a "minimal enclosure for capturing a reader's attention."2 By minimal, he means boring; by boring, he means experienced ambiently and durationally, like the hum of passing cars as one dozes in the backseat. All forms of cultural production, according to Lin, should aspire not to the book, "but to the condition of variable moods, like relaxation and yoga and disco."3

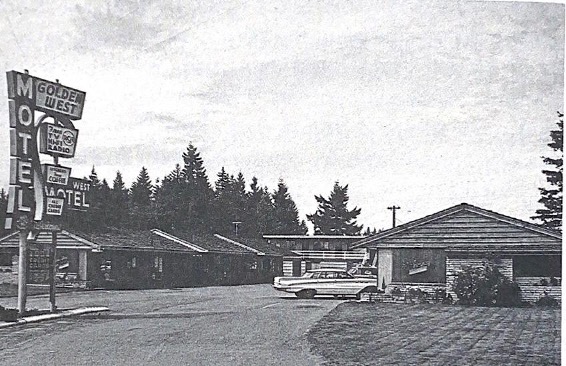

Lin's 2011 "ambient novel" Insomnia and the Aunt — best described as a conceptual elegy for a fictional relative — aspires, if only very loosely, to minimalism's formal qualities of implication, compression, depthlessness, and brevity. In a tone of seemingly flat, understated reportage across a lean 56 pages, the text consists of an almost paratactic accumulation of descriptive moments about a motel on the western edge of North Cascades National Park in rural Washington, run by a half-Chinese, half-English woman who happens to be the narrator's now deceased aunt. Footnotes index cached Google search results with no clear relation to their referents, the images that punctuate the text (among others: postcards, a photograph of Ronald Reagan feeding the titular chimpanzee in Bedtime for Bozo, a scan of Hollis Summers's 1972 poetry collection Start from Home) have little to no bearing on the narrative, and the narrator frequently lies, or misremembers. Dreamlike, elegiac, circuitous, and repetitive (though his preferred formulation might be "mild"), Lin's climate-controlled fiction pursues more the affects of lo-fi music or a muffled television broadcast from another room than the modulated intensity and intentionality associated with conventional literary practice.

Lin's practice evokes but diverges from the traditional genealogies of literary minimalism in the United States because it is linked to Asian American racialization, the supposed "weakness" of which as an ethnic category and typification as insufficiently animated offers us a way to rethink minimalism's central tenets of concision, allusiveness, and impersonality alongside race's discursive and aesthetic character. Rachel C. Lee, drawing from Frederick Buell and William Boelhower, defines Asian American "weak ethnicity" as "a self-consciousness of both the fractious plurality troubling this pan-ethnic identity, and the imitative stylings of other, stronger racial and ethnic formations."4 Sianne Ngai observes that Asian American subjects are often racialized as mute, inexpressive, and affectively inscrutable, standing "in noticeable contrast to what we might call the exaggeratedly emotional, hyperexpressive, and even 'overscrutable' image of most racially or ethnically marked subjects in American culture."5 Lin's own interest in the construction of an "ambient literature," which involves the relaxation of generic categories to recruit "bottom-up, non-directed, allotropic modes of general receptiveness rather than top-down, attention-based focus on specific objects or things," brings together the discursive and affective minimalisms of the Asian American subject to model a particular kind of reading practice.6

Insomnia and the Aunt alludes to Asian American racial form in a variety of ways: it cites the typification of minimal Asiatic affect in its muted, impersonal narratorial voice, satirizes the trope of the model minority in the figure of the insomniac aunt (because she does not sleep, she is always working), and expresses a sustained interest in opacity, falsification, and performance. The sleepless, televisual stupor of the narrator and his aunt might be said to resemble what Tung-Hui Hu has recently described as "lethargy" — a latency that emerges from "moments of ordinariness, such as waiting, killing time, impasse, and deferring a decision."7 Hu argues that the lethargic subject sounds the limits of liberal personhood and its cherished fictions of sovereignty, immediacy, and spontaneity, especially in conversations about what constitutes meaningful political action. Insomnia and the Aunt is similarly interested in how we might rethink the politics of racial representation by understanding what appears aimless or passive (like television-watching) as significant to the story of becoming Chinese American as the violences that aimless diffusion supposedly mediates. Alongside the text's wistful ruminations on Desperate Housewives and Tide detergent are passing allusions to 1960s Civil Rights, the Vietnam War, and the redlining the narrator's parents experience during their first year in Seattle.

In Lin's estimation, Insomnia and the Aunt "is not a 'normal' immigration narrative, mainly because it's not really a narrative. In this work, narration is replaced by description and static absorption in front of a TV."8 By foregrounding distraction, latency, and duration as foundational narratological principles, Insomnia and the Aunt's lethargydeforms and reorganizes what live(li)ness (affective, biological, and televisual) might come to mean for the racialized subject. Shortly after the text begins, the narrator recounts the televisual display that appears upon every one of his returns to Bear Park over the decades:

My aunt is crying in front of the lobby window, which is back lit like a movie set. She runs out, yanks the duffel from my hands and bump drags it two or three steps in front of me to room seventeen, which is the room my aunt always takes me to whenever I visit, just as Salvador Dali when he came to New York always stayed at the St. Regis and always in room 1628. Whenever I visit during the next decade, my aunt will perform the same actions, with the same deliberate energy I associate with following a recipe one knows very well or watching re-runs on TV. She will cry in exactly the same manner, in front of the neon NO VACANCY sign in the window, with the same uncontrollable wailing and tears and half-Chinese words I do not understand. None of this I can hear very well through the glass. When I think of these actions, they give off, like the paradox surrounding a guess, the appearance of slightness inside moments that have already happened, as if my aunt's life were endlessly re-passing a single point in time, like an actor in a sitcom or a car going past the same highway exit night after night on its way home.9

The narrator watches his aunt through the glass of a lobby window like a rerun or looped GIF. Much of Lin's interest in repetition is as much about the technological affordances of media (temporally asynchronous and ambiguously spatialized, as in canned laughter) as the pathos of the belatedness it formalizes: "Most of the talk my aunt and I do is posthumous by the time we're done talking. What my aunt didn't understand so well was that most relatives that we love are dead long before we get to them."10 The channel-flipping of tenses (between present and future) and moods (between indicative and subjunctive) in the passage above, as well as the searching and deferred figuration — each description insistently qualified by "like" or "as" — that nonetheless gets corralled into a ritual televisual cyclicality formally enacts what might be said to be a characteristically minimalist investment in management, constraint, and control. And yet, even as her actions appear "canned" — pre-recorded, rehearsed — they also serve as evidence of rigorously sustained care; the best re-runs, the narrator later informs us, would not recognize themselves as such while they are being watched. Live(li)ness here functions across different axes. The narrator's aunt is not yet dead; she is, in her wailing, animate; and her performance manages to retain its feeling of temporal immediacy, despite the lingering suspicion that this moment has already happened.

If "the beautiful thing about a death is that it keeps multiplying," Insomnia and the Aunt paradoxically constructs its minimalism through elliptical, self-contained, and often tautological elaborations of multiplicity.11 Details in the text accrete like boredom: as a "very loose medium in which the heterogeneity of the world can be gathered without coalescing into something meaningful."12 In other words, the "loose medium" of Lin's ambient text operates as an aesthetic strategy through which a novel might register without resolving what remains unassimilable into the fictions of the immigration and development of a Chinese family in America. The appearance of "Part II" — the text neglects to ever introduce a "Part I" — roughly two-thirds of the way through the text slyly comments on this. Not unlike the old episodes of Conan O'Brien and Star Trek that the narrator and his aunt watch late into the night, the "static absorption" that Lin associates with television-watching performs an anti-Bildungsroman function, through which ephemeral moments and feelings might accumulate and be experienced diffusely without hardening into the "biography of the lives one family tried to have in America."13

The central minimalist figure in the text is the vending machine — a racialized form that (given its associations with postwar Japan) often operates as techno-Orientalist shorthand for the kinds of inhuman, machine-like efficiency and automation associated with the Asian body.14 The dearth of convenience stores in rural 1970s Washington requires guests at the motel to rely on vending machines (curated by the Aunt) to supply the things they had neglected to pack. Among them:

toothbrushes, combs, condoms, cheap underwear, Elmer's glue, Coppertone suntan lotion, band-aids, Bayer aspirin, Duco plastic cement, Dramamine, hair bands, bobby pins, Cracker Jacks, fishing tackle and hooks, Kleenex, Prell shampoo, Dial soap, Bic pens, a packet of used postage stamps, Ho Hos, a tiny squirt gun (for the kids), a Duncan yo-yo (also for the kids), Drum chewing tobacco, a twenty-four shot roll of Kodachrome, a thirty-six shot roll of Ektachrome, legal size envelopes, a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer (for some reason, my aunt thought it was illegal to serve cold beer from the soda machine but warm beer was OK), a mini Swingline Stapler, rolls of coil tamps that she had gotten from the post office, and a few paperback novels left behind by guests, which [she] stuck into any unfilled slot.15

Here, the vending machine literalizes minimalism's formal economy — concision and containment — without its subtractive impulse. Can it (like a novel) nevertheless confess a depth and continuity, even as its contents refuse to cohere? Given Lin's longstanding interest in genre, it is interesting to observe what remains branded and "off-brand" in this assembly of commodities. This inventory is neither purely decorative nor merely utilitarian; rather, it is "an apparatus for the production of a soul, or at least a universal machine of observations in the world two people knew, each shaped like a flower or possibly the calculus of a brand name that perpetually adds and subtracts things from the world."16 By such logic, under the names of necessity and convenience, a vending machine might contain the world. Or, at the very least, the objects metonymically conjure a deceased aunt, who may or may not be an aunt at all (perhaps "just a Chinese auntie"), and who may or may not have ever existed in the first place.17 At stake in Lin's ambient, mediated minimalisms are questions of intelligibility and relation: an aunt of ambiguous relatedness; a versatile contraption that furnishes film, sunscreen, and souls; and the correspondence of depth to the flatness of a racialized surface.

The most significant question of relation in Insomnia and the Aunt, however, concerns the relationship between the events of the text and the empirical "facts" of Lin's life — the book is marketed as a "memoir" as well as "fiction," "biographical fiction," and "literary nonfiction." But can we have sincerity without honesty? Lin's wager is yes:

For the last few years and under some unknown compulsion I associate with rock music on MTV, perhaps it is the compulsion to lie or not lie, I have removed most of the photographs of my aunt from the album, one or two at a time, as if some sort of 'tell-tale compression' — not of the pages of a life, as in Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey — but of the images of a life taking place. I think my aunt would have wanted to be removed from a family or a chronology in this way, for as with the numerous and unpredictable additions to a life, so too with its subtractions.18

The affective arithmetic of such "additions" and "subtractions" subtends both the aesthetic project of minimalism (whose "subtractive" compression produces its economy of expression) and the literary genres of biography and autobiography (whose "additive" qualities congeal with varying success into "the images of a life taking place"). But if the genre of autobiography usually solicits "numerous and unpredictable" details that might be said to add up to a narrative, Insomnia and the Aunt offers us a narrative full of detail that remains unrealized in (or unassimilable to) that narrative and is instead dispersed as "mere" mood, as literary ambience.19 The typical immigration narrative of a particular (yet diffusely generic) Chinese American family is only background noise to the centrality of a television in a certain motel that is — and remains — always on.

And so what is at stake in repetition without meaningful accretion, like reruns and the restocking of a vending machine? In an aunt who, upon every one of your arrivals to her motel doorstep, weeps, takes your bags to room seventeen, and invites you to watch television with her? In the above passage, Austen's readers sense in her narrator's characterization of the "tell-tale compression of the pages before them, that [they] are all hastening together to perfect felicity," wherein the materiality of the print book — how many pages remaining? — might serve as an index of narrative momentum and closure.20 The repetitiveness and modularity of Lin's text obviates this expectation. Insomnia and the Aunt does not narratively taper to "perfect felicity"; it ends, fittingly, with an ambivalent observation about how a vending machine "mostly just looks like one of the versions of happiness [he] thought a family would have."21 But unlike the narrative density that clamors toward something like resolution, we, like the Aunt, are "endlessly re-passing a single point in time," which becomes diffuse enough to feel televisual. In Insomnia and the Aunt, "the end comes before and then it comes after," like an endless re-run of an aunt's happiness at your arrival.22

Irene Kim is a PhD candidate in English at Northwestern researching the ambient aesthetics of Asian American art and literature after 1960. She tweets sporadically @spatialconcept.

References:

- Many thanks to the editors at Post45 Contemporaries, and to cluster editors Michael Dango and Connor Bennett for their generous, incisive insights and their invitation to be a part of this cluster.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, "Ambiently Breaking Reading Conventions: Colin Marshall Talks To Experimental Poet Tan Lin," interview by Colin Marshall, 3 Quarks Daily, Jul 5, 2010.[⤒]

- See Tan Lin, "Interview for an Ambient Stylistics," Conjunctions 35, American Poetry: States of the Art (Fall 2000) and "Disco as Operating System, Part One," Criticism 50, no. 1 (2008): 97.[⤒]

- Rachel C. Lee, The Exquisite Corpse of Asian America: Biopolitics, Biosociality, and Posthuman Ecologies (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 9.[⤒]

- Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 93.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, "A Book is a Technology: An Interview with Tan Lin," interview by Angela Genusa, Rhizome, October 24, 2012.[⤒]

- Tung Hui-Hu, Digital Lethargy: Dispatches from an Age of Disconnection (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2022), xxi.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, "Your Closest Relative is a TV Set," interview by David Foote. Asian American Writers' Workshop, July 8, 2015. [⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 10. [⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 36.[⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 38.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, "Tan Lin by Katherine Elaine Sanders," interview by Katherine Elaine Sanders. BOMB Magazine, March 29, 2010. [⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 51.[⤒]

- See Erica Kanesaka's discussion of vending machines in the Japanese game Animal Crossing: New Horizons in "The Healing Power of Virtual Cuteness," Public Books, July 17, 2022; Kerry Segrave's discussion of Japan in Vending Machines An American Social History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015); and Micky Lee and Peichi Chung's co-edited Media Technologies for Work and Play in East Asia: Critical Perspectives on Japan and the Two Koreas (United Kingdom: Bristol University Press, 2021).[⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 49-50. [⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 50. [⤒]

- In the interview with the Asian American Writers' Workshop, when asked by David Foote if he did in fact have such an aunt in Washington, Lin answers: "No. But I did watch huge amounts of TV while growing up."[⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 38.[⤒]

- My profuse thanks to editors Michael Dango and Connor Bennett for this incisive formulation of biography's usual propensity for details that add up to a narrative vs. Lin's inclination towards "mood."[⤒]

- Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 233. [⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 51.[⤒]

- Lin, Insomnia, 49.[⤒]