The After Archive

And from Cain there sprang misbegotten spirits, among them Grendel.

— Seamus Heaney, transl. Beowulf (2000)

This is an excerpt from a longer essay, framed from just before the 2016 election through the present. It follows the three monsters of Beowulf, a poem written in Old English around the eighth century. In this, I draw on the 1999 translation by the poet Seamus Heaney, tracing his engagement with the ruins of the English language. The piece begins with Grendel, first of the poem's three monsters, who lives with his mother on the wasteland outside the hall of Heorot. Grendel and his mother are descendants of Cain, heirs to God's curse as their birthright. Each night, Grendel is drawn to Heorot to hear the harpists as they sing of God's creation, entering afterwards to kill the warriors in the hall. As the story begins, Beowulf, a visitor, has arrived at Heorot and heard the story of the years of slaughter.

*

In off the moors, down through the mist bands

God-cursed Grendel came greedily loping.

— Seamus Heaney, Beowulf (2000)

The Jack Russell is a happy, bold, energetic dog; they are extremely loyal, intelligent and assertive.

October 7, 2016

That morning we had breakfast in the Holiday Inn Express. I assembled Styrofoam cups of coffee and hot chocolate while Rosie poured every kind of cereal into a single bowl and we gathered at a table in the corner. On the television, the news anchors were discussing Donald Trump, whose so-called "Tic Tac Tape" had just been revealed, with his comments on grabbing women "by the pussy" and forcing himself upon them. The gist of the morning news seemed to be the question of whether the Republican presidential candidate should be understood to be a sexual predator. Rosie was the only child in the breakfast room, a tiled and otherwise anemic space; her primary focus of interest was the indoor pool on the other side of the picture window. She would be competing in the child handler class the next day, and we rehearsed the characteristics of the Jack Russell Terrier, its habits, its natural prey (groundhogs, lemurs, raccoons, and foxes). The room was filled with middle-aged men and retired couples, fixed on the scene of the morning news anchors discussing the presidential candidate's habit of sexual assault. We got up, collected cinnamon rolls to bring with us, and went to find Sharpsburg, Maryland, site of the Confederate defeat at the battle of Antietam and of the Jack Russell Terrier Club of America's 2016 national trials.

The battle of Antietam is remembered as the bloodiest single day of combat in the Civil War. Over twenty-two thousand soldiers died in an inconclusive battle around Antietam Creek, where Robert E. Lee had retreated with the Confederate forces on a mid-September day in 1862. It was fought around a cornfield, Miller's Field, as one general waited for relief troops to arrive while the other, filled with uncertainty, refused to press his advantage. You have seen the battle of Antietam: you have seen the bodies on the field, photographed by Alexander Gardner two days later and before the dead were buried, the bodies limp in death, identified and labelled by Gardner with titles like "The Confederate." The living were there as well, in Gardner's battlefield: standing uneasily, rake thin, angled against the light, waiting to bury the dead. Gardner's "The Battle of Antietam" was exhibited a few weeks later in New York City at Matthew Brady's gallery to public sensation; the images were copied as woodcuts in Harper's and elsewhere.1 All of this is related to me by the website of the National Park Service Antietam Battlefield Center, where a virtual tour leads through the fields and cornfields, what survives of a battle that would allow Abraham Lincoln to declare a victory and, on New Year's Day, to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.2 Although no one could know it, Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation were barely the mid-point of a war that would claim some 620,000 lives before its end.

Rosie and I followed my printed Google Maps directions, through the highway junctions, past the gas stations, the Waffle House, through the condo developments and the farm fields, to what seemed to be the entrance to the Washington County Agricultural Center. We stopped the car, rolled down the windows. The sound of a thousand excited Jack Russell Terriers echoed from the sky, like a battlefield, like Valhalla: we had arrived.

*

In his translation of Beowulf, the poet Seamus Heaney writes of Grendel as a puppy, a licking, lonely predator. "He will carry me away as he goes to ground," says Beowulf to Hrothgar, "gorged and bloodied; he will run gloating with my raw corpse and feed on it alone, in a cruel frenzy, fouling his moor-nest." Ac hē mē habban wile / drēore fāhne, gif mec dēað nimeð.3 Heaney gives us the warriors, gathered around Beowulf to listen, trustfully sleeping in the hall that night as Beowulf keeps watch for his prey. Uncomprehending, solitary, forsaken, it appears: "In off the moors, down through the mist bands, God-cursed Grendel came greedily loping." Ðā cōm of mōre under mist-hleoþum / Grendel gongan, Godes yrre bær.4

Heaney was forthright in his ambivalence to the poem. He had "no special fondness" for it, he wrote, unlike other Old English poems in which he could hear the language, the "voices shaken by the North Sea Wind . . . voices crying under the ness." He writes that he worked at it in spates, no more than twenty lines a day, for a few days at a time. "I did it in sheer concentrated bursts like that," he writes, "in longhand, on big lined notebooks, looking up the meanings of the words, co-ordinating with the cribs, prospecting for alliteration and so on." He describes himself as "like a man sentenced to hard labor, rolling up his sleeves, spitting on his hands and taking hold of the shaft of a sledgehammer." In the course of things, every so often, he says, he "would indeed warm, as they say, to the task."5

Heaney came back to Beowulf. He started in 1984 or 1985, he says, after the publishing house Norton suggested the idea. It was at this point that he completed the draft translation of the opening and first hundred lines. A manuscript draft of Heaney's opening is held in the collections of the British Library. "So. The Spear Danes held sway once," he begins. And, in succession:

So: the Spear Danes held sway once.

So, The Spear Danes in Days gone by

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by6

When he came back to it in 1995, he came back to this. "First time round I'd got my 'So' for a starter," he says, "and my 'thole' for a seconder; by line 13, I'd turned young Prince Beow into a 'cub', which is what he'd have been called in south Derry in the 1940s."7

Heaney followed the language back from the North Sea to the north Atlantic, and the linguistic refuge of county Derry in Northern Ireland where he had been a child. He describes this in his lecture to the Friends of the Bodleian Library on translating Beowulf. "My soul frets in the shadow of his language," he quotes from James Joyce's Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, explaining that his lecture's first point was that Joyce had "cleared 'fret' of that negative charge and allowed Irish writers to say what I make Joyce's shade say in 'Station Island', 'The English language belongs to us'."8

*

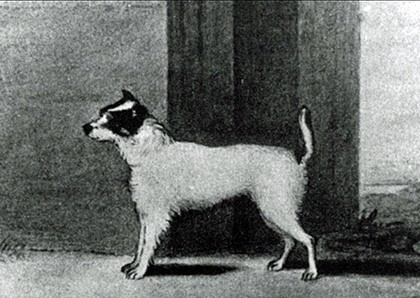

Trump was the name of the first Jack Russell Terrier. Technically, she was the ur-Jack, the progenitor of a line of terriers bred by the Reverend John Russell over the nineteenth century in the south-west of England. Her portrait, commissioned by Edward VII, is said to hang in the harness room in Sandringham House. Taken some five decades after her death, it shows a bristly white dog, dark spots on her ears and eyes. She waits in characteristically alert stance: ears pricked, tail upright, head tilted to observe. Even in the grainy, black and white copy that I find online, her legs and body are tensed for action.

Trump is a shadowy figure, almost a cipher; she could easily and perhaps more persuasively be fictional. She is given to us as a character, written decades after her life in her owner's biography: A memoir of the Rev. John Russell and his out-of-door life, originally published in 1878. In this history, she emerges on a May morning in the last years of George III's reign, trotting next to her owner, a milkman, in the suburbs of Oxford. That day, the young John Russell set off from Exeter College while studying for his exams, crossing the Cherwell in a punt and tramping out of the city toward the farm fields and hunting grounds in the hills beyond. Here he saw Trump, beside her owner. "Such an animal," as his biographer described, some five decades later, "as Russell had as yet only seen in his dreams; he halted, as Actæon might have done when he caught sight of Diana disporting in her bath."10

The Reverend Russell bred his terriers to hunt. They were, and are, intended to be small enough to follow a fox down into a hole. In the show ring, the judge will lift the terrier up to feel the size of its chest, the term for which is "spanning." Too large, and the terrier can't fit in or, more critically, out of the hole. Once there, the terrier's job is not to attack the fox or kill it, but to persuade it forcibly to leave. The dog does this by growling, nipping, and crying at it, an anxious grating sound, habitual to the breed, called "worrying." A Jack Russell Terrier will worry its object, whether this is a fox or a rawhide chew or an owner. They are intent, focused, monomaniacal; they have few barriers between observation and action; they are foolishly reckless; they will dive down into a hole without inhibition and stay there, fighting, until they die or are taken out. They have no incapacity for courage; they are born and doomed to it; it is their very nature. "Tartars they were, and ever have been, beyond all doubt," writes the Reverend Russell's biographer.11

*

"From Cain there sprang misbegotten spirits," Heaney writes, "among them Grendel."

The story of Beowulf is a family history, the long afterlife of God, the father, and his grandsons, Abel and Cain. Grendel, "banished and accursed," was Cain's heir; his inheritance, the wilderness in which Cain wandered. His life is an exile, the "Lord's outcast," punished endlessly for his birthright. "Spurned and joyless," Grendel arrives, maddening for blood at the sight of Hrothgar's clan, sleeping together in the hall of Heorot, the "ranked company of kinsmen and warriors," all quartered together in their home. And when Beowulf fought him, calling on God to help, Grendel's thoughts went to his own legacy, longing to "flee to his den and hide with the devil's litter." After Beowulf's attack, Grendel crept back to his inheritance: "broken and bowed, outcast from all sweetness, the enemy of mankind made for his death-den."

That night, after the celebratory feast, the songs and speeches, the gifts, the praise for Beowulf, the warriors go to sleep again in the hall. Grendel's mother — "monstrous hell-bride," Heaney calls her — comes from the mere in which she is exiled, emerging from the cold depths of water on the moors beyond Heorot, "grief-racked and ravenous, desperate for revenge."

*

"Bitches over 12 ½ inches" was our racing category. I tucked Pips under my arm and waited in line with the other owners before the heat. She had been assigned pink as her racing color, and the official slipped a pink cloth ruff around her neck. I flipped a domino to see where she would start; we drew box one, on the end, not her best position. The six of us lined up with our dogs in front of the racing chute while the lure, an artificial fox tail on a retracting cable, was pulled down the length of the track. Pips watched, shaking in my arms, waiting to start.

"You bound the hell's dogs and deprived them of their preys," reads Richard Morris's 1868 translation of an Old English homily. Þu band ta helle dogges, and reftes ham hare praie.12) The Oxford English Dictionary offers this as the earliest English usage of "prey," definition I: "A person who or thing which is hunted, pursued, or plundered." The text is taken from Wohunge of oure Lauerd, or The Wooing of our Lord, an Old English text held in Cotton Titus D. xviii.13 Praie or preie, prey, might look the same as preie, pray, but this is a coincidence; then, as now, the two derive from a different origin.

*

A dog was the first living creature to orbit the Earth. In the early days of their space program, the Soviets practiced with dogs. Thirty-six were launched in satellites into orbit or sub-orbit; fifteen survived. The dogs were strays, lured from the streets with sausage, kept if they were below a certain height (34 cm), weight (6 kg), and length (43 cm) from nose to tail. In a BBC documentary, Lyudmila Radkevich describes driving with a military escort around Moscow with a tape measure and food, trying to find dogs that were small enough.

Laika, the first to be sent into orbit in the Sputnik 2 program, died of overheating and stress some four hours into her flight on November 3, 1957. Her stone effigy is part of the façade to the Monument to the Conquerors of Space in Moscow, built one hundred and seven meters high in titanium to celebrate the achievements of the Soviet people in the space age. Another monument was erected in 2008, showing a bronze dog standing on a rocket; in the photograph, red carnations are at her feet. Years earlier, Dezik and Gypsy had made a sub-orbital flight, returning safely; Dezik was sent up again on July 29, 1951, and died when the parachute failed to open on return.

Belka and Strelka, who survived eighteen orbits of the Earth on the Soviet Kornble-Sputnik 2 on August 19, 1960, are shown in effigy in the Cosmonautics Memorial Museum, on either side of their space capsule. Chaike and Lisichka, their predecessors, had died the month previous when their rocket exploded at launch. Damka and Krasavka crashed after a failed orbital flight on December 22, 1960, landing in the wilderness, where the dogs survived another day in the spacecraft in the snow before rescue. One of Strelka's puppies was named Pushinka, and given to John F. Kennedy's daughter, Caroline. "We were interested in breeding because we wanted to know whether animals could reproduce after space travel," Radkevich states, "Would it have any effect on them and what would the offspring be like?"14

Belka and Strelka had already become celebrities. Archival footage shows them at a press conference, post-flight, one held in each arm by Radkevich, both wearing their individually tailored cosmonaut costumes. Posters and lunchboxes showing the two dogs in their rocket survive. An animated film, "Star Dogs," was released in Russia in 2010, a child's tale of their capture from the streets, their flight into orbit. In the film, the dogs search for Sirius, the father, brightest star in the night sky. The archival footage, the cartoons, the interviews, the BBC documentary: these can all be found on YouTube. You can watch the footage: in the space capsule, the dogs don't seem small. There is always a moment when they look back out at their viewers.

*

He set the sun and the moon

To be earth's lamplight, lanterns for men,

And filled the broad lap of the world

With branches and leaves; and quickened life

In every other thing that moved.15

*

God's outcasts are also his survivors. "Grendel was the name of this grim demon," Heaney writes, "haunting the marches, marauding the heath and the desolate fen. He had dwelt for a time in misery among the banished monsters, Cain's clan, whom the Creator had outlawed and condemned as outcasts."16 Each night, Grendel returns to Heorot, a "prowler through the dark," "harrowed" by the "din of the loud banquet," the harp being struck, the poet singing of God's creation of the Earth and man, the story of his own disinheriting.

Sunnan ond mōnan

Lëoman tō lëohte land-būendum,

Ond gefrætwade foldan scëatas

lëomum ond lëafum

And what of Beowulf? What of his inheritance? He was Ecgtheow's son, he tells us. "All over the world," he says, "men wise in counsel remember him." He is unnamed in the poem until he stands before Beow's heir, Hrothgar, and calls himself Beowulf. He is unknown, unrecognized. No one at home seems to have tried to stop him from leaving. "What kind of men are you who arrive," the coast-sentry asks, "rigged out for combat in coats of mail."

What about the other ending, the one where Beowulf arrives at Hrothgar's court with his military escort, the one where he is Ecgtheow's son, the one where sons do not need to know, where they are freed from the knowledge of their fathers. Here the son of Ecghteow goes out at nightfall from the hall, the harps, the clan of the Danes with their old stories, their retributions. Here the son of Ecgtheow finds Grendel, sees him, offers him a bit of sausage and a story, hand-stitches him a costume, selects and prepares him for purposeful training in the service of the State, studies the effects on sexual reproduction, afterwards builds the well-furbished ship with its ring-whorled prow, ice-clad, outbound, a craft for a prince. And they set a gold standard up high above his head and let him drift to wind and tide, bewailing him and mourning their loss.17 What would the son of Ecgtheow be named? What would the poet sing, when he left to return across the sea-lanes in his steep-hulled boat?

*

"Under my window, a clean rasping sound," Heaney writes in "Digging," first poem in his first poetry collection, Death of a Naturalist (1966), "When the spade sinks into gravelly ground: / My father, digging."18 Heaney looks down through the window over decades and generations, seeing his father, his grandfather, and himself, as a child, bringing milk "corked sloppily with paper," to his grandfather digging turf:

He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf.

It is in the turf that Heaney finds his father's language, in the "cold smell of potato mould, / the squelch and slap of soggy peat / the curt cuts of an edge through living roots awaken in my head." For Heaney, language is rooted in the earth, something to be dug, with work and precision. "Between my fingers and my thumb / the squat pen rests," he writes in "Digging." In "Station Island," he writes Joyce's voice as "definite / as a steel nib's downstroke, quick and clean"; his character meets Joyce last, twelfth in the progression, through the Dante-esque pilgrimage through his past.19 By God, the old man could handle a spade.20

*

Rosie lines up in the ring with the judge. She stands alongside the others with her dog, offering a scrap of cheese to the disinterested Pips, who is more concerned with whether there will be rats to chase. I cannot look at anyone but Rosie. There she stands in her pigtails: scruffy, upright, radiantly intent. Can I be the only one to see? She is the edge of a steel sword; she cannot help but cut and be cut by it, cannot help but observe.

We place fifth, a pink ribbon. Rosie holds this before her. She is shimmering with joy. Months later, there is a photograph in the Christmas issue of True Grit, the magazine of the Jack Russell Terrier Club of America. It shows the child handlers circled together by a hay bale, Rosie holding her ribbon up before her. The dogs, breakers of mead-benches, are not included. There in the ring, we collect a bag of Jack Russell Terrier child handler prizes — beef jerky, dog cookies baked in the shape of bones, a stuffed and immediately beloved terrier — and walk through the rain with Pips back to the car. We are soaked, shivering, joyous; we start the car, turn the radio on, reverse out and begin the drive back home.

Kathryn James is the Curator for Early Modern Books and Manuscripts at Yale's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and a co-organizer of the Yale Program in the History of the Book. She is the author of English Paleography and Manuscript Culture, 1500-1800 (2020).

References

- Merrell Noden, "A War Brought Home," Princeton Alumni Weekly, March 19, 2014.[⤒]

- National Park Service Antietam Battle Visitor Center, Accessed January 7, 2021. [⤒]

- Heaney (below), p. 31, lines 446-450.[⤒]

- Seamus Heaney, transl. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation (bilingual edition) (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2000), p. 49, lines 710-711. This essay began when my husband gave me a copy of the Heaney translation, on which this essay is based. Maria Dahvana Headley's translation (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020) has since added immeasurably to the translation history of this work.[⤒]

- Dennis O'Driscoll, Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney (London: Faber and Faber, 2008), 440. [⤒]

- Seamus Heaney. "Beowulf," typewritten drafts with MS annotations; 1995. British Library Additional MS 78917. [⤒]

- Ibid, 439.[⤒]

- Ibid, 435.[⤒]

- "An oil-painting of Trump is still in existence, and is, I believe, possessed by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales; but as a copy, executed by a fair and talented artist, is now in my possession, and was acknowledged by Russell to be not only an admirable likeness of the original, but equally good as a type of the race in general, I will try, however imperfectly, to describe the portrait as it now lies before me," from Edward W.L. Davies, The out-of-door life of the Rev. John Russell, a memoir, new ed. (London: Richard Bentley, 1883), 62.[⤒]

- Davies, The out-of-door life, 61-62.[⤒]

- Davies, The out-of-door life, 65.[⤒]

- Richard Morris, Old English Homilies and Homiletic Treaties of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries (New York: Greenwood Press, 1969 ed[⤒]

- Art, 4[⤒]

- BBC Four, "Space Dogs" (2009); See also Olyesa Turkina, Soviet Space Dogs (London: Fuel Design & Publishing, 2014).[⤒]

- Heaney, "Beowulf," lines 94-98.[⤒]

- Ibid., lines 102-06.[⤒]

- Ibid., lines 47-50[⤒]

- Seamus Heaney, "Digging," Death of a Naturalist (1966; repr. 2006, Faber & Faber), 1.[⤒]

- Heaney, "Station Island."[⤒]

- Heaney, "Digging." [⤒]