The After Archive

Siddhartha Lokanandi, who owns a bookstore and arts event space here in Kufürstenstrasse called Hopscotch, told me two things in our first meeting that he believes to be true about Berlin. First, he said, Berlin is a city of archives, then later, in another conversation, he said, It's a city of paper. I have also learned in my walks through the city and in first conversations with other new friends that it is a city of memorials and self-recrimination. The implications of these four aspects — archive, paper, memory, responsibility (apology?) — are vast, tangled, multilingual, happening at intersections of streets and times, happening between bodies present and absent.

I am not the archivist in this story. I have been invited to make work in conversation with the archive. But I am also not the researcher. I am invited in under a strange category that not everyone at the archive agrees upon. I am the experimenter. Do we let in an experimenter among our shelves upon shelves and rows along rows of paper and objects?

I think many of us in whichever country we're in are tuned in to the necessity but also problematics of the archive. In some ways, what draws me most to the archive (i.e., to the idea of the archive, of archiving) is the near impossibility of addressing the question upon which most seem to be founded: how do we build lines between places and events and persons — places that sometimes were temporary, events that were obscure, people that history often regards as minor characters. This opens into further quandaries: what do we put in which box, which box do we pull, and what word do we give this box, in this moment of our storing it, compiling it so that later we know where this life is, so later we have a context in which to place this life?

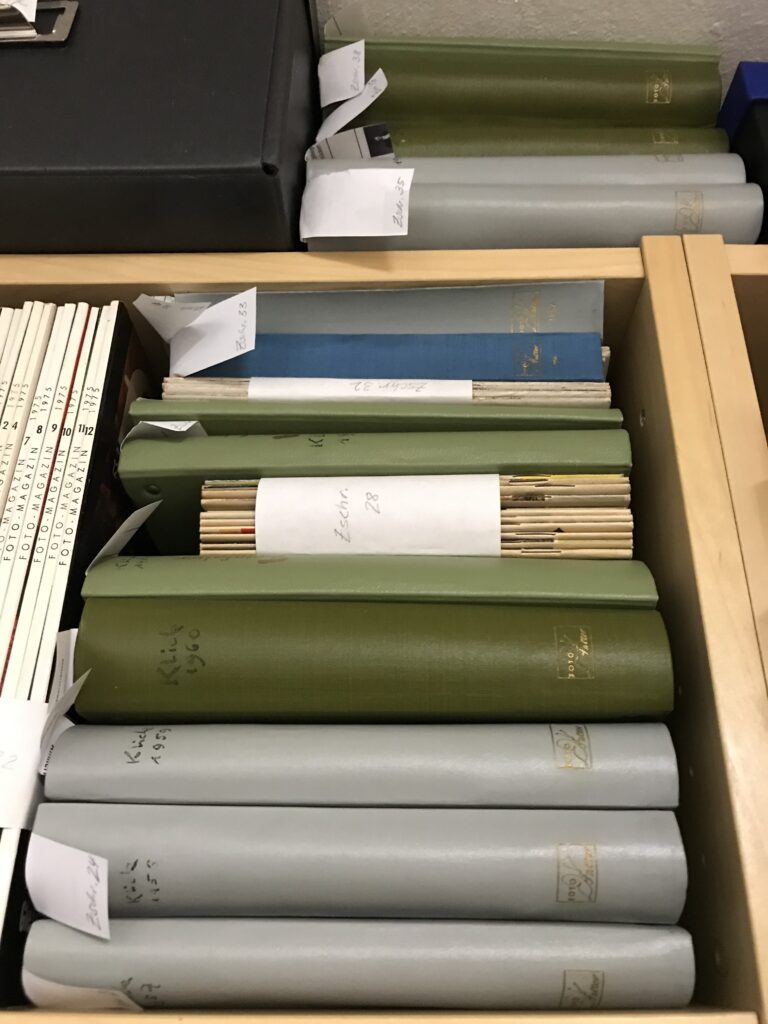

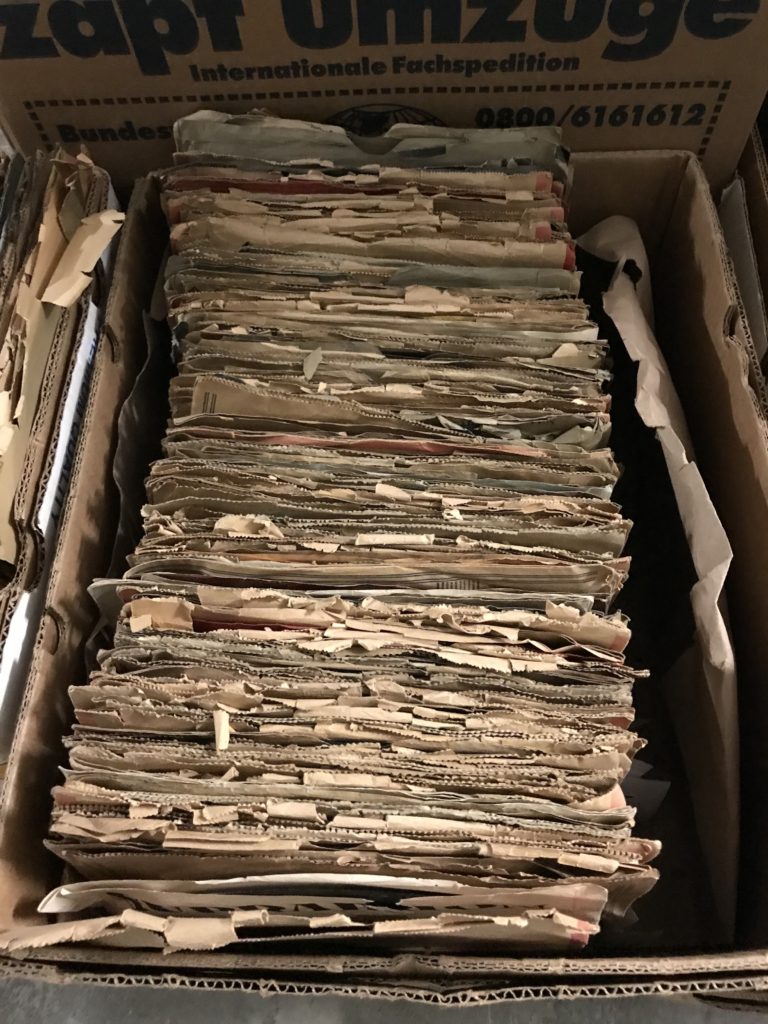

I am in my third week of a yearlong residency, where I live in one museum and work in the archives of another museum. I have a German tutor and we have had two lessons, so, at this moment, the extent of my German is being able to call out the names of the objects in my apartment. To say yes and thank you and please and receipt. Thus, I found the invitation to work in the archives of this German museum both daunting and thrilling. At the moment, I feel compelled to withhold the name of the museum, to give it time to make order out of a mass of donated materials from all over Europe, to find the keywords that link these pages and photographs and posters and graphic work and VHS tapes into some kind of electric and consolidating history, and to figure out how to trouble these holdings by looking at what's missing, who's been left out.

This archive is largely devoted to the living of a certain category of men: their activities, what they did with their bodies, how they organized and protected themselves. It's a vital gathering of material, but it's not exactly the material of my dreams or my demographic. I like women. I like maps. I like scores, formulas, equations, constellations. I like buildings and the stories of buildings. But I also like space and problems of space; I flourish in confusion, and I never had a moment where I would say anything but yes to this opportunity. I found the questions profound: how do I navigate columns of historical facts given in a language in which I am illiterate? How do I see the rooms containing these rows, make sense of the shape of this not-knowing? Was this another way to get at the connection between architecture and narrative, where my disposition (as when I'm drawing writing without actually writing) allows me to see the two categories as forms, as relation? In an archive where you are not beholden to content, you are . . . ? This was the open-ended question I would take with me as I entered the space for the first time.

It turns out it would depend on the architecture of the archive. That is to say, by not being beholden to the language of the archive I still hoped to meet it; yet, for me to meet it, the archive would have to come alive for me in other ways: something about its layout, something on the floor, something in the naming or organizing, how the labels of the files were typed out, which finding guides were employed, something striking or beautiful or labyrinthine in the objects or furniture collected. I needed to find a problem that would keep me.

The first problem I encountered was one I hadn't anticipated. After my initial tour of the archive, which was cursory at best — I managed only to capture a few images of the finding guides and notations for a few of the rows — I learned that I was expected to conduct the rest of my exploration of the archive from a reading room on the upper floors. That is, no one is really allowed in the archive other than the archivists themselves. I could see how that might be a rule, but it confused me with regard to my own residency, since it would be impossible for me to read the German-language card catalogue located in the library so as to request the German-language files in the archive, having myself no German. Had there not been agreement among the principal players as to the nature of my work there?

It was a moment, where one museum (the one that housed me) saw me as a kind of maker, an active wanderer, where the physical space of the archive was integral to whatever I produced, while the other museum (the one that promised to provide the house for my proposed thinking throughout the time of my residency) saw me as a researcher, a reader, who understood that the actual space of the archive was unbreachable, was not a traversable space, was not a space itself. The archive was in the paper, in the countable items, in the order and arrangement of things. I could only think that the reason one invited a monolingual black US southern-born lesbian writer-artist to engage a largely monocultural, German-language-based collection of ephemera dedicated to the ongoing of a certain category of men was with the intention of fissuring the confines of that particular archive. From my perspective, my entering the space of the archive would be, by necessity, discordant, and would disrupt not only the stories held within but also my own story. I would not expect anything different. I would never imagine entering a space that bore almost no trace of my origins without breaking it and myself. And, in this instance, that drew a very clear line between what it meant to be an artist and what it meant to be a researcher encountering this material. Without language comprehension, my only option was to go in with my body. So, what do I do if my body is not allowed in the space?

Once this first problem was resolved — while the museum that houses me and I were not entirely successful in demonstrating the benefit of my presence on the actual floor of the archive, a kind of bewildered permission was granted; the agreement: I'm allowed one or two visits down into the annals if there is someone from the museum's Board to chaperone me, and if I don't attempt to touch anything myself — once this first problem is resolved, I am poised and infinitely more excited to face the second problem. How do I find portals or resonances within the body of the archive that will allow me to see myself in the archive, to find the right question or the right confusion that would open into a field of study, a field for studying?

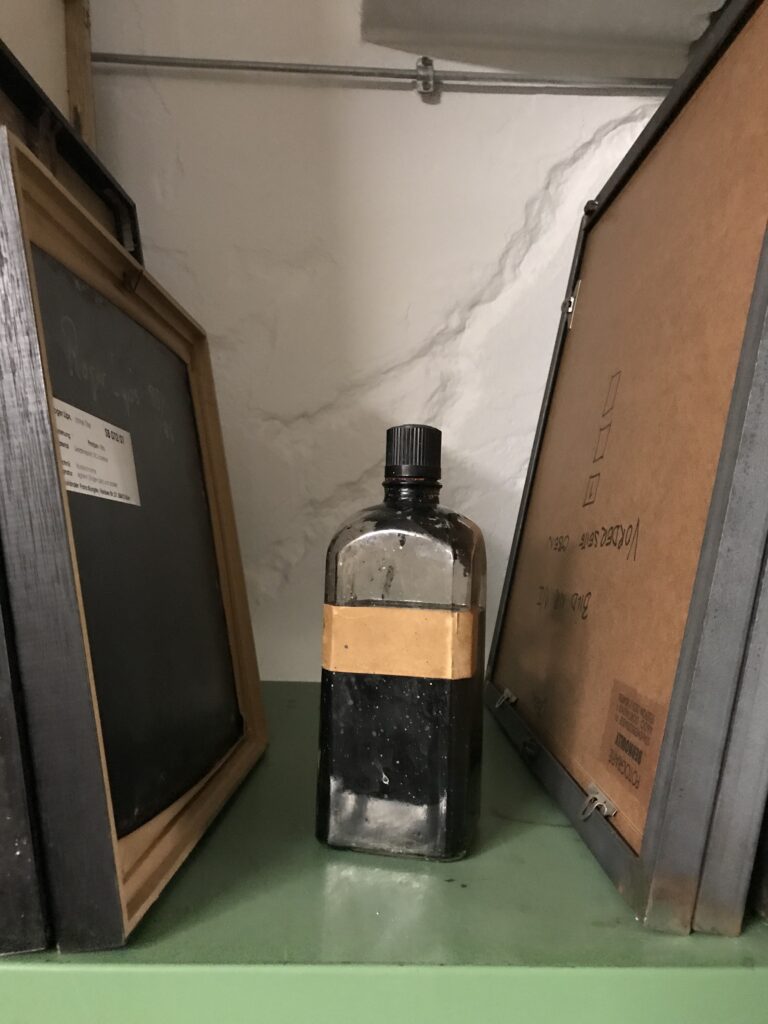

Upon my return to the annals, the first thing I did was gather objects:

I have always felt I shared a link with things in a room, with trees, and with rocks. I was confident that if I looked at these things long enough, if I listened to the machine sounds or stared at the floor, looked deeply or off-handedly into a corner or at some script written on the side of a box, something would open. I have always been able to get myself excited about nothing. I have always known that nothing was something.

But in this instance, I couldn't get any traction among these objects or their shadows. While I can imagine being admonished for misappropriating the archive — i.e., someone might argue, the archive floor is not a space of wonder, the wonder begins with your question, which the paper of the archive not its architecture or poetics could answer or at least attend to — and I do agree there is something irreverent or supercilious about the experimenter looking for inspiration in the architecture of the archive, which maybe belies the archive itself. Mine was a response to the condition of illiteracy with regard to the archive I've been invited to study. How could I think anything but "I've been brought here to mess things up," bolstered by a kind of optimism that whatever my intervention was it would be something the archive needed.

So, as I've been saying, though now I'm definitively saying it in the past tense, as I'm no longer in Berlin and haven't been there now for nine months — as I was saying, I stood for a long time in different areas of the main room of the archive, where most of the material that has been processed is stored. I looked at the floor, I looked at the walls, I looked at the paintings encased in bubble wrap. I noted the trinkets on the shelves, I saw the collection of t-shirts and pens and postcards that had been duly catalogued; I saw the divergent drawer dedicated to a few women whose papers and ephemera had managed to work themselves into this growing but still largely singular history belonging to this certain category of men. We (the objects and me) were at a kind of standoff. The question I couldn't shake, which was perhaps incorrect of me to ask to begin with, but which came unspoken, in my opinion, with the invitation to live and make work in Berlin and in this particular museum, was one of belonging. I was being asked to find myself within this archive, thus by accepting the invitation to do so I, on some level, was agreeing to the possibility that there was, could be, concordance between my living and the living captured therein.

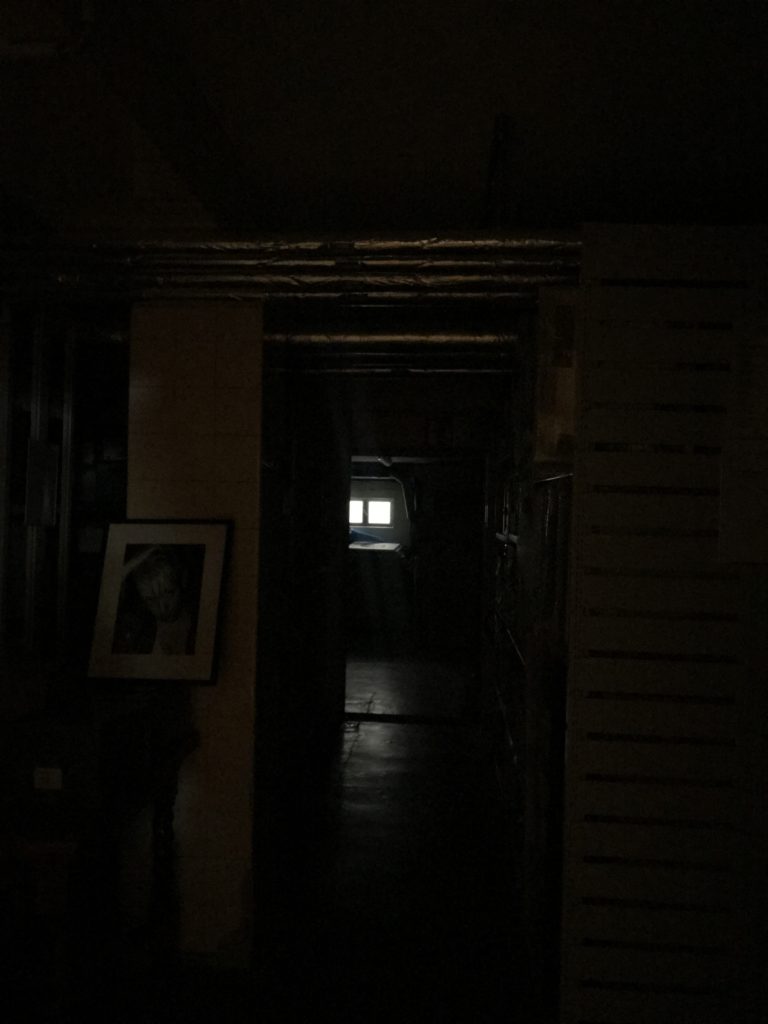

The moment the archive became tenable for me was when I turned to explore the back rooms of the storage area (rooms I'd toured briefly on my first visit) and found them shrouded in darkness. Simple solution: hit the lights, illuminate the back rooms. But I was stunned into inaction. I, for the first time, felt something. I felt what was wrong. It wasn't so much that I was bored by the materials of this particular archive as it was that I was hurt by my absence here, or rather hurt by the lack of threads or a logic that would lead me to finding a place for myself here, which in some ways told the story of my entire year in Berlin and, truthfully, my adult life in general.

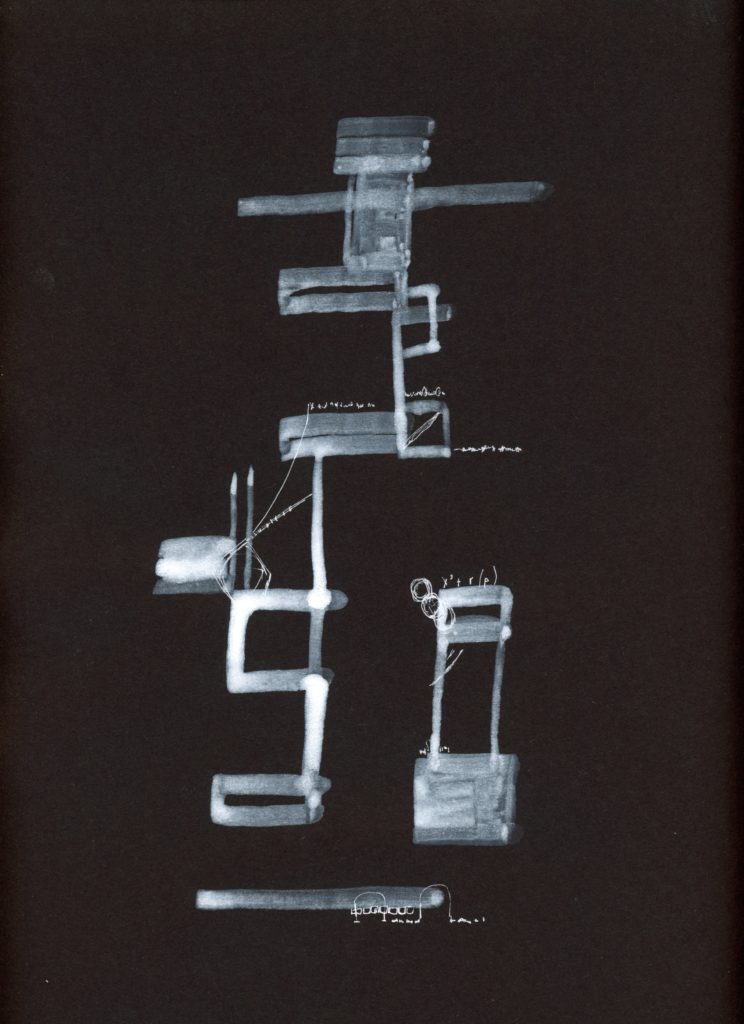

This is the origin story for a project entitled Math of the Invisible / The Non-visible file of the Gay Museum, which I may never finish. It begins with the dark and a need to distinguish between that which is invisible and that with is non: in other words, making weight of the difference between experiencing one's absence from the terms of perception (the parameters of the archive, the historical record) and the coming-to-know of that un-perceived space, a vibratory and populated field within darkness. There was an immediate math to this recognition that I could get to through drawing, that I could begin to navigate by first accepting the fullness of this vivid black space: listening to it, rather than seeking illumination.

***

(To Be Continued)

Renee Gladman (IG: prosearchitectures) is a writer and artist preoccupied with crossings, thresholds, and geographies as they play out at the intersections of poetry, prose, drawing and architecture. Her published works include of a cycle of novels about the city-state Ravicka and its inhabitants, the Ravickians, as well as two monographs of drawn writings.