The After Archive

"The Foundation of This is laid in Truth of Fact; and so the Work is not a Story, but a History," wrote Daniel Defoe at the beginning of The Fortunate Mistress — published anonymously in 1724, now called a novel, now known as Roxana. In a pandemic, in the midst of vast illness and grief, the facts are important, the facts are elusive, time is muddled. I know what I know in pieces. In 1990, in my late twenties, I was part of the way into a graduate program in literature and at its edges; was trying to live with my failed attempts to care for friends who were HIV positive, and not only them, but hundreds of thousands of people I never met but felt connected to; was watching the apparatus of medical science flailing, ineffective, sometimes compassionate, often vicious, after its little mid-twentieth-century run of omnipotence and violence. I had spent some years tending others' lives and work, trying to keep those jobs; was now reading all day long. I had a ruptured connection to my own history and found a thin comfort in Defoe's insistence that his books were made of historical facts, confusion at his pleasure in the work of accounting for oneself, wonder at the prevarications of "the novel."

For a long time, I believed that I had no right to write about anyone, even myself. No right and no ability: calling up the simplest phrase to account for my life was a struggle; asserting something about another human: freighted with difficulty, risk. A formative period of being told that what I knew and felt was not the case helped shape that impasse, made me skeptical at the core about many forms of knowing. As have the formative and ongoing practices in this country, beginning with extractive settlement and enslavement, in which counting and accounting for oneself were inextricable from treating others' lives as countable, as property, as instrumental, as insignificant, or else to be removed.

It was 1990, possibly early 1991, which is to say, still the long 1980s, deep in the free fall of AIDS, which is to say, a time we still inhabit. I know that sometimes I was observant; often so scared that I could hardly see. I know the dead are gone and here, insistently. I know I cannot smell or touch them anymore. In any case: "Thus fluctuating, and unconcluding, were my Thoughts," says Defoe's Roxana. "In short...all confus'd, and in the utmost Disorder." Not many pages later, deserted by a husband, she narrates a tableau of distress — "sitting on the Ground, with a great Heap of old Rags, Linnen, and other things about me...crying ready to burst myself" — that is also an occasion to account for the stuff once hers: "Pictures and Ornaments, Cabinets, Peir-Glasses, and every thing suitable." I was as rapt and vexed by Defoe's long pauses to enumerate conjoined things and feelings as I was by his characters' vexed spying on and attempts to fathom one another, their constant lying while professing the truth, all of the acting out and narrating of scenes that never happened, as if of fact, by them and by the book itself: the thing called fiction.

I sit here now surrounded by paper, books, images, and clothes belonging to friends who are gone, particularly by a box and bag of stuff that belonged to Jim Lyons, the film editor, actor, writer, and AIDS activist, whom I miss every day. Sit surrounded by all I saw and don't recall, by what I did not see but can't forget, by the fleeting-lasting rhythms of friendship, by my own silences, through the confus'd, fluctuating, unconcluding time of ongoing pandemic and grief, ongoing inequitable health care, at the outset of a new pandemic — "novel," and with more of the same inequities. It is happening still, happening again, not coming to an end, will not be over even if it does. And as with every event, catastrophic or banal, there are those who are able to live as if it never happened, is not happening.

All of these are facts. But I'm trying to bridge some gap, not write a treatise. Or trying to right an un-treatise. To write a bridge. And to hold onto my friend.

Jim Lyons was a filmmaker. Yet he was never a director of his own work. Best known as the editor of the first five movies of the director Todd Haynes, he also edited feature films for Sofia Coppola and Tom Gilroy, among others, acted in several key films of 1990s US independent queer cinema, consulted on countless other films, curated events for film festivals, was known as a brilliant practitioner in his medium and milieu. On his death in 2007 at age 46 from HIV/AIDS and illnesses associated with it, he left many deeply researched and imagined but unproduced works for film, as well as unpublished poems, autobiographical writing, correspondence, and more — in notebooks, his computer, and printed pages. A film project that is not filmed is — A kind of hypothetical statement? A non-event? An immateriality? A question? A failure? To its non-maker, in any case, can attach an aura of missed possibility, or sad deficiency. I say "not filmed"; I should add: not edited, the sound not mixed, not distributed, not all of the other processes and forms of work that bring a movie to an audience.

But Jim's unrealized work makes powerful reading. His papers are the materials of a filmmaker who was perpetually thinking about his medium, a writer trying to keep writing, a person with HIV trying to stay alive. His journals are not medical records — those no longer exist, or at least I can't get them — but they contain intensive evidence of his experience of and questions about his illness and of the new, uncertain information he sought out constantly, as he and others became experts in their own treatment, most of it experimental. Over twenty-five years, he was sick and well and sick again, trying always to think and feel his way through it, working and not, and when not, always worrying about getting back to work. He wrote in his notebooks when and as he could, given the normal chaos of life and the extraordinary stress of living with this diagnosis before the advent of therapies that have made a different kind of life with HIV possible for some today. Often he reflects on being confronted anew with that pandemic and his own diagnosis. He also used these journals as address books and as places to take notes on the films he was cutting. Sometimes he is in the hospital; sometimes he is in the editing room; sometimes at home; sometimes he does not note where he is. Systematic, objective marking of space and time was not his point.

*

"My goal has long been to create my own emotional, thoughtful, culturally critical films," Jim Lyons wrote in a grant application in 2004. "I have not found a way to do this along with supporting myself." In the late 1970s and early 1980s, in his late teens and early twenties, he had "resolved to wait to make my own work" and focus on film editing "as a way to get a practical grounding in my craft," as he wrote in 2004. By then he had long confronted the "AIDS phobia" of the industry, in the words of his friend the filmmaker Stephen Winter: "It wasn't that he didn't have the ego of a director, or didn't come from money. There are people who don't come from money and still make movies. It was because he had AIDS."

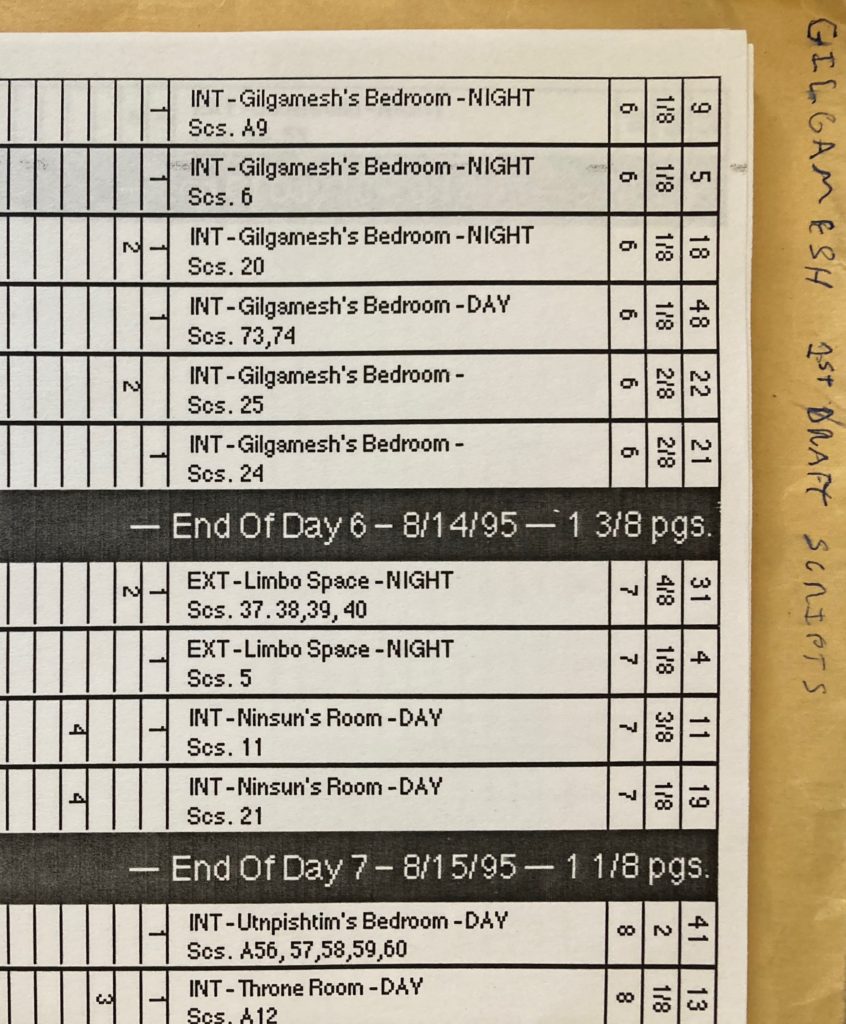

Most of Jim's film treatments and scripts drew on documentary and narrative film practices; several mingled historical and fictional figures. Often in these works he was thinking, directly and metaphorically, about the history of stigma and of experimentation — medical, emotional, aesthetic — that he was living through and making, and about its connection to longer histories of repression and radical politics. For the last couple of years of his life, in and out of the hospital repeatedly, often living there for weeks at a time, sometimes editing a friend's film on a laptop computer in his hospital bed, he worked on pre-production for his script titled "A Short Film About Andy Warhol," for which he had received a major grant. At the same time, he was writing a feature-length script for a film that mixed the life of Michel Foucault, bold visualizations of Foucault's writing, and a fictional narrative about a young African American philosophy student and punk rocker; this script was titled "The World and All the Dreamers in It." And, for almost twenty years, he tried to make a film of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

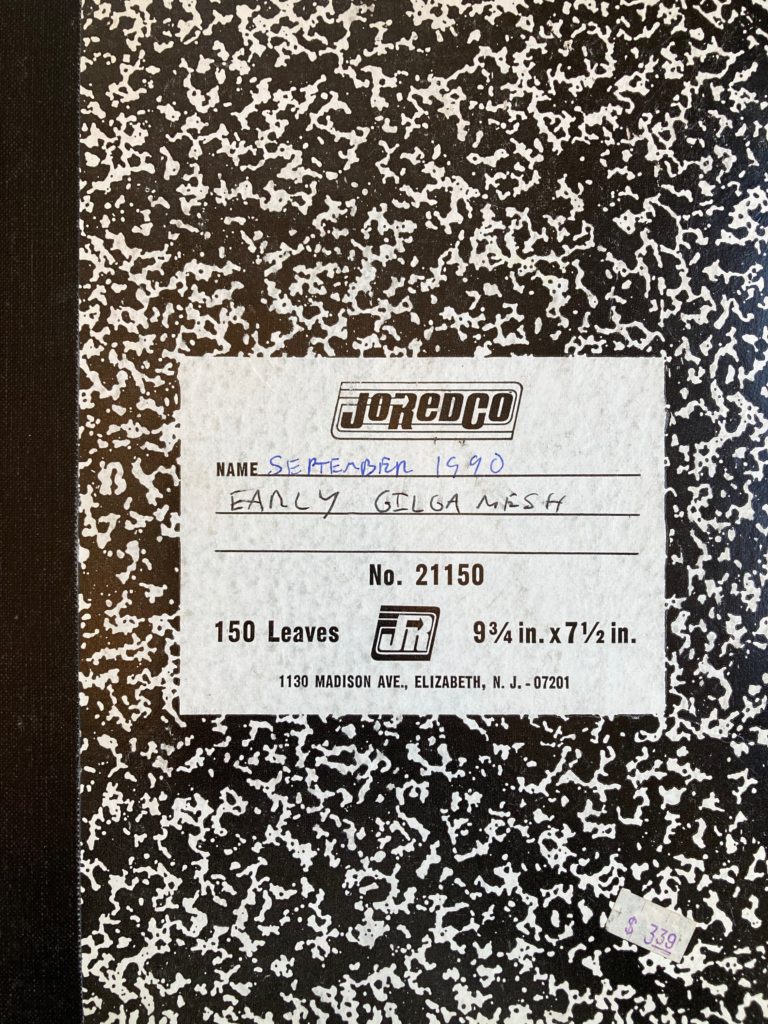

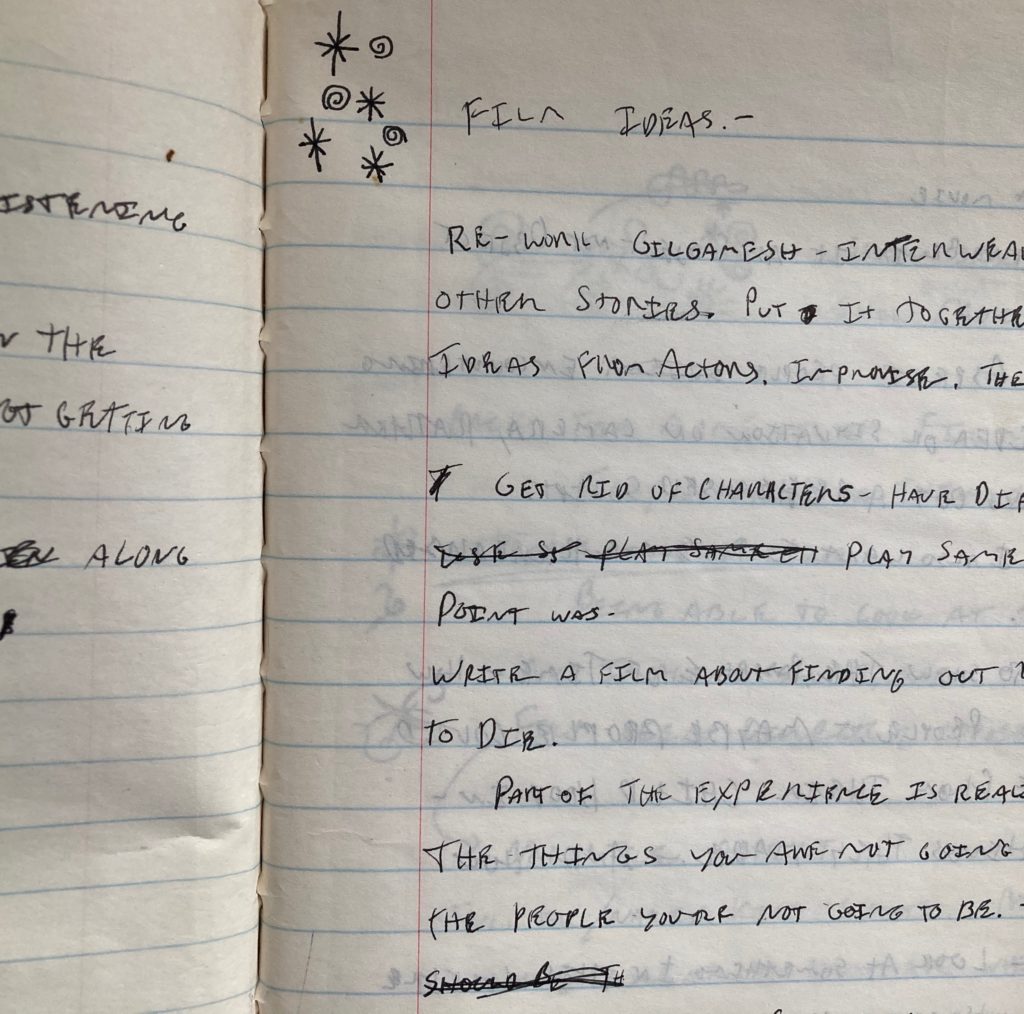

Jim understood Gilgamesh to be about the meaning and power of dreaming; he was moved by it as a love story between two men; he saw it as a critique of martial masculinity and he used it as an occasion to think about US violence in the Middle East; he knew it as a long cry against death and loss; he took it as a chance to reframe representations of illness, noting that while he had first loved this text as a teenager, it was when he realized he was HIV positive in his late twenties that "its themes of compassion, mourning, and the fragility of the body" came to the fore for him. The oldest epic poem in world literature, and the oldest written literary work, Gilgamesh was composed in a cuneiform alphabet on clay tablets. It survives only in fragments and has been translated and reassembled multiple times (to speak only of its versions in English). Jim worked on at least three iterations of his own project of translating the epic to contemporary moving images. One he described as "an experimental documentary in which people with chronic illness both talked about their life experiences and played the parts of the narrative." He wanted to mix the ancient story with current facts, mix others' persistence and pain with his own, mix film forms. "Combining strategies taken from documentary, narrative, and avant-garde genres," he wrote in a notebook he labeled "September 1990 Early Gilgamesh," it would be "an attempt not to choose. Bound to fail but that doesn't take away its power." In another notebook from around the same time — writing in the hospital about two years after having tested positive for HIV, writing under the heading "Film ideas" — he exhorted himself:

Re-work Gilgamesh. Interweave it with other stories. Put it together with other ideas from actors. Improvise.

Get rid of characters. Have different actors play same parts

Write a film about finding out you're going to die.

Part of the experience is realizing all of the things you are not going to do, all of the people you're not going to be.

. . .

Breakfast is here.

He would "take different parts of the subjects' lives and collage them together.... The effect will be somewhat like the 'cut up' novels of William Burroughs or the automatic writing experiments of the surrealists but with a much clearer unifying structure." He would make a film about the solitariness of mortal illness, and the power and limits of love, representing the points of view both of the one who dies and of the one who is left. Channeling the cadences of the epic, or quoting one of the translations he owned — I'm not sure which — he wrote:

It is an old story

But one that can still be told

about a man who loved

and lost a friend to death

and learned he lacked the power

to bring him back to life.

His film would be composed significantly of its participants' voices — their responses to a series of questions about their lives that he would ask them, as well as performed scenes from Gilgamesh — and would be "constantly dissolving from documentary to fiction and back." "The filmmaker," he wrote, will be "in the position of Gilgamesh — trying to keep people alive. Learning he can't."

Returning to this project a couple of years later, he wrote that the work was about dynamics of "arrogance" vs. "acceptance," about how two intimates who are different negotiate the world together — a fundamental question, also not a trivial matter for someone who was usually in sero-discordant relationships. He wrote that Gilgamesh was about "the longing to preserve that which will be taken. To document to have to fix with us forever the experiences, the beauty, of the world each person constructs for themselves to live in."

"Death as the fixing of identity," he wrote.

"Vanished lost gone," he wrote.

In the winter of 1993, diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis, still sick from this fungal infection, but at home starting to recover, he wrote, in a green softcover Clairefontaine notebook:

Thursday — Karl [Hoffman, his doctor] called. Blood test is good but not as good as I thought. I still have a way to go.

. . .

(Lisa came + brought soup)

. . .

I feel like writing. I can't do much else but sit at home.... I'm not sure I want to work on any of my old ideas — Glitter script, Gilgamesh, military script/Church script, SM/AIDS, etc. I found an envelope filled with Gilgamesh prep the other day, started to cry. Don't look back.

The first several times I read these lines I didn't understand the person bringing the soup as me. I wondered who that Lisa was. Was I so absorbed, reading his accounts of his life, that I forgot my own? So consumed by his writing, and by the minutiae of transcribing and editing it, that I forgot our friendship, though it was what propelled me through his pages? So habituated to self-erasure? Eventually I did a kind of double take and remembered the long freezing walk downtown I had taken that February day from my apartment to his, remembered the place where I'd bought him lunch, remembered sitting together as he suffered from the cold, from crushing headache and ringing in his ears, from frustration, uncertainty, and despair about his work. I remember trying to comfort him. I remember all of the comfort he brought me over the years, this friend who knew difficulty speaking as inextricable from love of language, who had also grown with the fact and fear that, as he put it, "anything could happen."

A couple of years later, he completed a feature-length script of Gilgamesh that he titled "The Serpent." He applied to the Independent Television Service (the funding and distribution body founded in 1991 to support innovative public television) and wrote in his proposal that Gilgamesh, "the main extant literary work of the Sumerians, oldest culture of the Western tradition (and the culture that seems to have invented the earliest Western writing system) is clearly a homosexual love story of the greatest beauty and tragic dimension." The word "friend" occurs throughout the text, and translating Gilgamesh to the screen Jim was also writing self-consciously about how friends support one another and fail to, about the intimacies and distances that develop when one of them begins to die. He wrote: "The film explores mourning and the possibility of immortality." In his script, Gilgamesh says to Utnapishtim, survivor of the great flood:

My friend, whom I love, Enkidu,

...

My friend has died so many times

within me

and yet he still seems so alive.

Is there something more than death?

Some other end to friendship?

He planned a cast and production team that would center "people of color, especially of Middle-Eastern descent." He had commitments from several noted performers and other film artists. Again, he would cast people who were HIV positive. "People with chronic illness," he wrote in the grant proposal,

are constantly figured as either noble, or bitter victims. They are seen as mostly responsible for their health status except in certain cases, in which they are judged innocent or undeserving. Either judgement comes predominantly from outside the community of patients, care givers, lovers, friends and family directly connected. Patients themselves have views different from even the people they love, and certainly from that dominant culture. This film explores these experiences on a philosophical level and will be made by members of that community, who see assignment of guilt both as a sad joke and the least of their worries.

He wrote to this audience of potential funders that much of his own time was "spent seeking out treatments, supporting friends and attending memorial services — trying to handle the unhandleable. I am politically active whenever the opportunity presents itself and I try to make my artistic production a cogent political act." He noted that several of the films he had worked on, including "Poison" (1991), as editor and actor, and "Postcards From America," as an actor, "directly address the AIDS crisis, as do some of my own projects, none of them yet realized."

He described his film-to-be as having several aesthetic sources. The first was the epic itself: its "simple strength and unhurried dignity," which the linguistic and visual texture of his teleplay would "preserve." He would convey the sense of "obsession with language" and "the physical manifestations of text" in Babylonian and Sumerian art, the ways that textual material was "fully integrated with and often printed on image[s]." He would emphasize the epic's reliance on "standard tropes of storytelling which the [ancient] author assumes the audience will already know." Other aspects of Gilgamesh that he valued:

A concentration on the beauty of individual passages. A quality of frozen movement — still but about to change. The use of many voices. A reluctance to fragment the human figure. Pictorial composition that contrasts planes of intense patterning with bare space. A discursive, rather than linear narrative, which all of these conventions tend to break down.

His inspirations also included filmmaking traditions: "the poetic, studio-produced fables of narrative film making" (Charles Laughton's Night of the Hunter, Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast, F. W. Murnau's Sunrise, the art direction of William Cameron Menzies and Harry Hausen) and the work of experimental makers Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, Jack Smith, Jean-Luc Godard, Bill Viola, and Jean Genet, which he planned to mine "for ideas of very simple visual story telling along with experiments with time and duration." He would shoot in black and white, but hand-color portions of the film and use some stock footage. He wanted to "try to maintain an air of [the work] coming from an ancient culture not like our own." In addition to dialogue spoken by "many different...voices," and title cards that harkened back to silent film, he would use "group chanting to tell the story."

He saved several identical printed copies of the script, including one on which a trusted reader observed that the explicit sex scenes — there were at least two — would not help him to get funding. But these scenes were key to his concept of the film and were a kind of gauntlet Jim threw down, given ongoing moves to suppress public funding for "explicit" art. One scene is between Enkidu and the Priestess; the other, between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, was his response to historic erasures of same-sex love. He wrote in blank verse. He relied on two translations, by Herbert Mason and John Gardner, but also "tried to teach myself a Sumerian style." "Many of the scenes," he noted, "are my own."

At one point, about halfway through the script, "we begin to make out Gilgamesh's shadow" as he walks slowly, on his failed quest for immortality. An intertitle follows:

46. TITLE ON BLACK:

. . .

He could see neither before him nor behind.

Days he traveled in blindness,

. . .

To quiet his fear

he said his friend's name.

He felt there was no end

to loneliness.

Eventually Gilgamesh meets the winged warrior and ferryman Urshanabi, who first refuses to take him to the underworld and tells him: "Forget your grief, live."

50. Exterior

. . .

GILGAMESH

"How can I keep still, how can I be silent?

The friend I love has turned to clay."

*

The writer is in the position of Gilgamesh — trying to keep him alive. Knowing she can't. But sitting with Jim's drafts, re-presenting his unfilmed writing on, of, toward, and in conversation with Gilgamesh, writing a book about him and with his writing: these are some of my ways to insist there is no end to friendship, continue our conversation about reading, love, and politics, keep living with his belief in all of our collective and singular vulnerabilities to one another.

I should say that I was by no means his only close friend. I should say that I never read any of this work — his notebooks or Gilgamesh scripts — until eight years after his death, almost as many years after having brought his papers to my home. I should say that in 1990 I started writing about my friends who were sick and dying, but for two decades resolutely did not write about Jim. It was only after his death that I thought to. Until then, he was his own vital work in progress.

I read two editions of Gilgamesh while Jim was alive — the prose translation by N. K. Sandars, which she published in 1960, and a version by the poet David Ferry, published in 1992 — because of what the epic meant to him. Ferry writes:

Gilgamesh, weeping, mourned for Enkidu:

It is Enkidu, the companion, whom I weep for,

weeping for him as if I were a woman.

He was the festal garment of the feast.

On the dangerous errand, in the confusions of noises,

he was the shield that went before in the battle;

he was the weapon at hand to attack and defend.

A demon has come and taken away the companion.

...

A demon has come and taken him away.

Eight years after Jim's death, working with his writing, I also read Andrew George's version of Gilgamesh (published in 1999). Unlike Sandars's prose or Ferry's verse, this text does not try to make the epic whole again; it is full of ellipses, bracketed words, and editorial notations. "A lacuna intervenes, then the narrative continues:" George asserts, repeatedly.

"A lacuna intervenes, then:"

"A lacuna follows the opening line of Tablet II, and when the text resumes the lines are still not fully recovered"

"Here another lacuna intervenes"

"After a lacuna intervenes, the text continues, though it is not completely recovered."

Death has taken him away. I am and am not a woman: it is as if I were. The friend for whom I weep was a shield. Not someone to hide behind, but who created an open space that made it possible to exist. On the dangerous errand, in the confusions of noises, I stalk a place replete with elision, aware of some of his dreams. There is no hero. Gilgamesh, weeping, in Ferry's edition, explains his loss to the elders of the city, tries to say what it means for Enkidu to be gone — and keeps talking to his dead companion, reciting their joint deeds and his grief. Gilgamesh, weeping, wants everyone and everything to mourn as he does: "the wild ass" and "the furtive panthers," the gazelles, the land itself — the way through the mountains, the path to the forest, the river — and the people who sent them on their journey, warning or blessing them. When you grow up hiding and shamed, few elders send you on your journey, or send you with imprecation. You grow yourselves up, hide the travel, find precious companions to accompany you.

The title of this essay is "A Lacuna Follows"

And the title of this essay is "The Friend I Love Has Turned to Clay"

The title is "Group Chanting to Tell the Story"

The title of this essay is: "Get Rid of Characters"

The title of this essay is: "How Can I Be Silent"

The title is: "My Own Projects, None of Them Yet Realized"

Lisa Cohen is the author of All We Know: Three Lives; is completing a book on queer friendship and the long history of HIV/AIDS; also has work in the London Review of Books, The Paris Review, The New York Times, The Vassar Review, and Adult Contemporary; teaches at Wesleyan University.