New Literary Television

If I read one more declaration that the novel is dead and that it is identity politics that have killed it — as though Victorian literature was not at all about identity politics — I might scream. But that's no way to start an essay about literary television, is it? To the extent that clickbait headlines about the novel being dead and television dramas replacing novels have been around since the coexistence of both forms, a serious conversation about for whom is the novel dead and why might actually be a productive way to begin thinking about how the HBO Series I May Destroy You (2020) treats the literary among other kinds of cultural prestige.1 If there's one thing that Robert J. C. Young has taught this postcolonial critic, it is that the desire to pronounce the demise of something tends to suggest not so much its end but rather the lingering of its presence, which is disturbing to those who would prefer to see it gone.2 I begin with the enduring demise of the novel as a point of entry for discussing what I May Destroy You tells us about the contemporary intersections of race, gender, and the economy of cultural prestige.3 I argue that in its conflation of authorial agency with individual mastery and material success, I May Destroy You offers informing contexts not only for thinking about competing spheres of cultural capital, but also for illustrating how it is with commodified experiences of their own traumas that Black female and non-binary writers in particular successfully navigate these spaces.4 From these informing contexts, as they are explored in the HBO and BBC co-produced series, we can learn much about shifts in the prestige literary landscape as they are mediated by social media and identity politics that take us beyond xenophobic declarations of the novel's demise.

Before I get into a fuller discussion of the show though, allow me two digressions into present-day social media, one here and one later, as a way of setting up a necessary and intricately connected cultural backdrop. Recently, there was an unsettling — to me — series of mostly white celebrity confessions about their bathing practices. First Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher spoke publicly about how rarely they washed their bodies and only washed their children's bodies when they could "see the dirt on them."5 Then Kristen Bell and Dax Shepard also discussed their abstentions from bathing, adding that they too "wait for the stink" on their children before they bathe them.6 Sure, daily showers "could cause skin problems or other health issues" and so it is perhaps best for those of us who occupy human skin to not be too fastidious about washing ourselves.7 What's important here though isn't whether or not the questionable personal hygiene habits of celebrities and their families is better for the skin or more environmentally responsible, but rather the publicness of these prideful declarations.8 Against the backdrop of racist histories where the personal hygiene of people of color was and continues to be aggressively policed, "the stink" as it is worn or even spoken about publicly has different material implications for some than it does for others. The luxury not only to eschew washing yours and your children's bodies, but also to speak boastfully in public about it, without fear, is a privilege.

I've taken this tangent into the caucasity of cancelling bathing — in an essay that I promise is about I May Destroy You — to help illuminate how Michaela Coel's series also explores related instances of white arrogance and entitlement that disregard the racialized complexities underpinning seemingly banal things. In its portrayal of a struggling writer, the show helps us to understand some of the implications of cancelling the novel, particularly at a moment in the form's history when it is serving underrepresented writers in ways we have yet to fully apprehend. It also helps us to understand how such dismissals are connected to larger structures of cultural commodification and profit.9 A question we could ask ourselves, as I May Destroy You's Pastor Sampson does, is "why must the white man chop at the neck, when the Africans only now beginning to swallow, huh?"

I May Destroy You centers on Arabella Essiedu (played by the show's creator Coel) and her friends Terry and Kwame, all self-assured and carefree Black Londoners. After the success of her first book — Chronicles of a Fed-up Millennial, released as a PDF for free on Twitter — Arabella is recognizable by Black women on the street who want to take selfies with her, is represented by a literary agency called Future Voices, and has an advance contract for a second book with a prestigious publisher, Henny House. All seems to be going well for Arabella until one drunken night a man spikes her drink and rapes her. The show follows her attempts at putting her life back together, ostensibly so she can finish her draft for Future Voices and Henny House. We also learn that she's gone through her advance in the last year and, through an embarrassing payment declined incident in the show's seventh episode, "Happy Animals," that her credit cards are maxed out. More than the triumph of completing a novel, Arabella needs to finish this book to meet obligations to her agents and the press, and more pressingly to make ends meet.

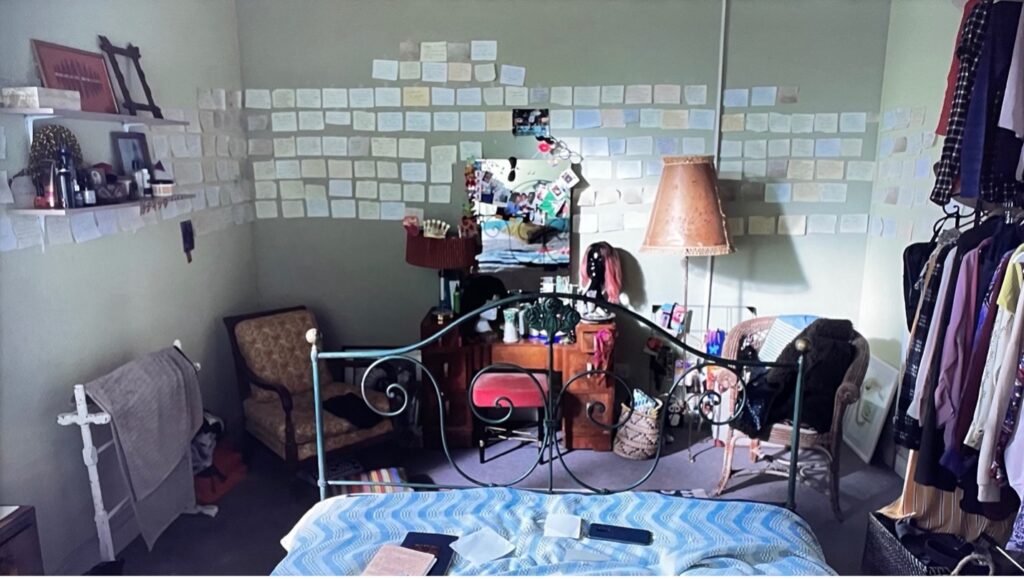

It's against this backdrop of financial need that the series' rape plot is joined by its literary one. The show's opening shot is of Arabella's bedroom; it is framed as a view from the foot of her bed, where a journal, a pen and bits of paper are scattered, and the wall opposite the bed is plastered with neat rows of sticky notes. The camera slowly pulls back from the wall and then the scene switches to one of Arabella and her Italian boyfriend, Biagio, waiting for the rideshare that will take her to the airport as she travels back from Italy to London. The opening scene is one that stages a version of writerly-ness — that is, in the midst of a drafting process. In the twelfth and final episode of the show, this scene returns as the site where Arabella is finally able to beat her writer's block, exorcize the demons of sexual trauma that haunt her bedroom, and finish her second book.

A lot happens in the intervening episodes, though, which blend Arabella's coming to terms with her trauma and the work of abandoning her novel to produce a creative non-fiction book. I know what you're thinking; Arabella's shift from the novel form to creative non-fiction — a craft move facilitated in the series' penultimate episode by Zain Sareen, a Cambridge graduate who had the contract for his first novel before the end of his final year — might suggest that, even for Black British women who grow up in immigrant households, the novel is indeed inadequate as a form of narrative that can convey the fullness of psychological complexity in innovative ways. But the circumstances under which the eventually disgraced Zain's own novel is pseudonymously published also serve to communicate how cancelling the novel ignores the different and complex social and political ways this embattled form functions for non-white people, much like bathing.

In her essay "Aspirational Labor in I May Destroy You," Sarah Brouillette observes that the Arabella's "working through" the trauma of sexual violence is "a working through [ . . . ] that becomes inseparable from the activity of writing itself."10 Arabella's full recovery of her memories from the night she was drugged and raped also neatly coincides with the breakthrough that finally allows her to finish the book she has been struggling to write throughout the series. By the show's end, Arabella has written and independently published a work of creative non-fiction that the audience is encouraged to assume is about the toxic culture of sexual violence that she fell victim to, that her friends Kwame and Terry also fall victim to. While this is all presented in the expected triumphant way, I agree with Brouillette when she describes the show's parting scenes at Arabella's reading for her newly published book as "idealized bookishness."11 Moreover, that "it is hard not to conclude that this portrayal of blissed-out bookishness ultimately props up the value of the kind of self-managed creative work that the show otherwise depicts as so difficult to do." What Brouillette refers to here is how the show makes Arabella's financial difficulties visible. There's the declined credit card, and the desperate partnership with a predatory vegan brand. It is ironic then, that even as Arabella overcomes the exploitation of the prestige publishing industry — one that seeks to capitalize on both the legion of fans she brings to the table as a popular social media influencer and her rape — the show reinscribes at its end a celebration of literary prestige.

Here, I am not so much interested in television that is about literary production, as I am in what representing literary production does for a television show. Coel's literary fantasy is also one of authorial agency of the kind that one might imagine people who write and publish books independently have. Moreover, it is a version of authorial agency that Coel is able to achieve herself with I May Destroy You by rejecting Netflix's distribution offer, which denied her any copyright ownership, in favor of a deal with the BBC in which she was able to retain her rights to and creative control over the show.12 Even as the show assembles a narrative of literary aspiration to demonstrate a fantasy of ownership over one's work, however, it also seems conscious of how the prestige of the literary can be overdetermined in situations where it is social media that generates the excitement the publishing industry seeks to capitalize on in its targeting of influencers like Coel's Arabella.

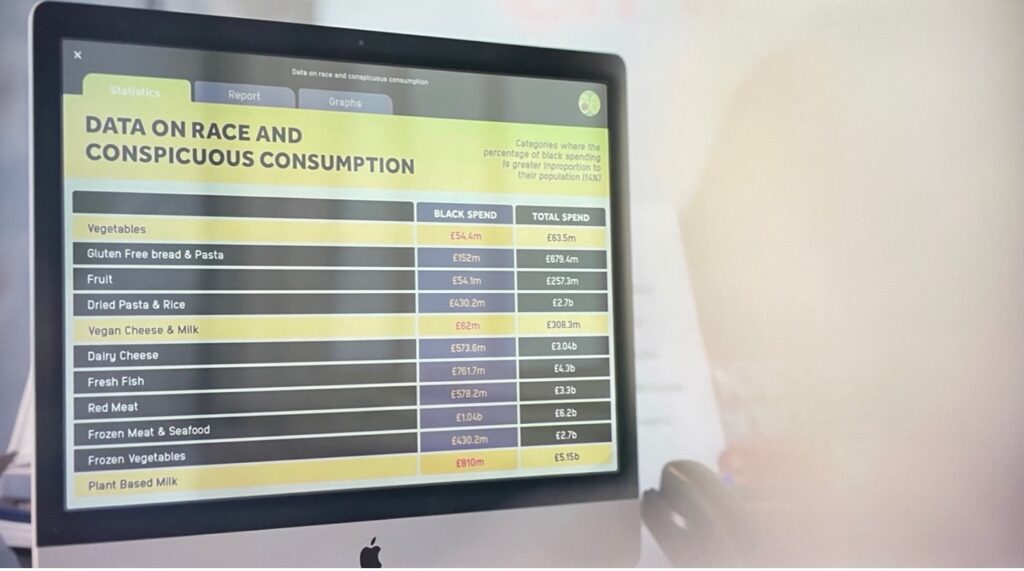

Among the things the show explores is the commodification of a specific kind of raced experience that is indexed not so subtly through both its portrayal of the prestige publishing industry and the diversity consumer industry. This is demonstrated by Terry's audition for the "feminist beauty campaign" early in the series, and the vegan delivery service, Happy Animals, for which Arabella becomes an influencer later. Both purport to be inclusive and actively recruit Black women, but neither is appropriately aware of what it means to meaningfully include Black women. The feminist beauty campaign thus humiliates Terry by asking in the audition to take her wig off so they can see her natural hair — a request they'd know would be out of pocket in that setting if they really intended to be an inclusive beauty campaign. This incident foreshadows when Arabella is recruited by her friend Theo — a white woman and leader of the sexual assault group she attends — for the vegan delivery brand. Theo gets a bonus for adding Black influencers to the team, to increase its visibility in Black communities. Arabella fittingly calls Happy Animals the "ethical Amazon" to the owner's discomfort. A view of a computer screen featuring data on race and conspicuous consumption, as the Happy Animals bosses give Arabella their spiel about veganism as a solution to ecological collapse, reveals that there's something more afoot than addressing climate change. Here again, the veracity of the righteous ecological claim isn't what's important. The data displayed on Theo's screen details categories where the percentage of Black spending is greater in proportion to their population, thus revealing a predatory racialized business model. Given earlier scenes of maxed out credit and Arabella's unsuccessful bid for more money from her publishers, one can't help but think how much economic precarity impacts meat-free choices in this context.

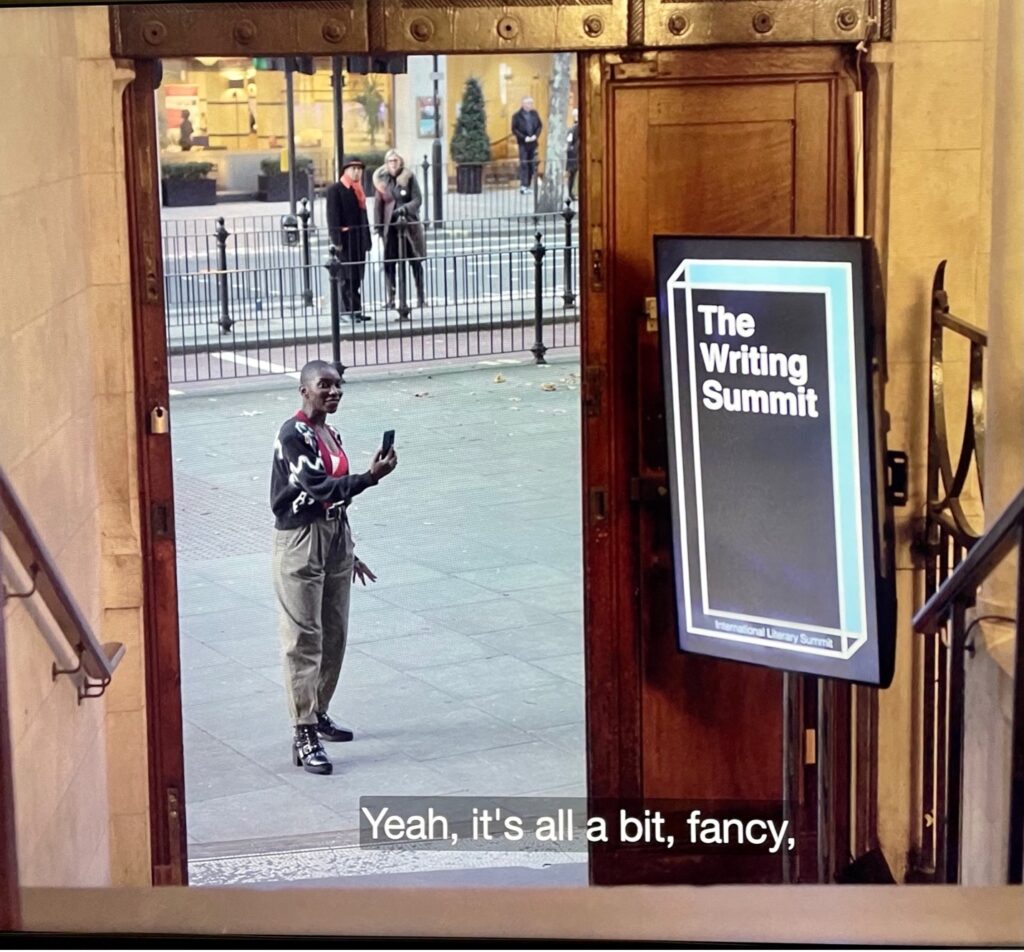

What I want to draw attention to here is how the value added by race and gender to both these brands is very similar to the workings of Future Voices and Henny House, with their courting of non-white writers like Arabella and Zain and their staging of events for emerging voices such as the International Literary Summit. In episode five, Suzy Henny, the Black head of Henny House, bestows Arabella with a coveted spot to read her work at the summit. That the summit's logo bears a striking resemblance to that of the Booker Prize indexes some of the show's more subtle concerns about the relationship between non-white writers — the formerly colonized — and the publishing industry. We know Henny House is prestigious first because it publishes work by another, more traditionally emergent writer, Zain, whom the press sends to help Arabella get her novel draft together. And then there's the iconicity of the summit's left-aligned blue and white logo.

In what might be dismissed as classist banter serving solely to establish the difference between Zain's literary pedigree and Arabella's (Cambridge graduate versus published via Twitter), both of their answers to the question "what's your background" reveal contemporary publishing's raced priorities. That is, though Arabella's cheeky "Ghana" is met with Zain's equally saucy "India," both responses demonstrate Commonwealth literary agendas that seek to capitalize on the postcolonial popularity of representations of racial difference — struggle in particular — within the contemporary literary marketplace. Here are a handful of other examples from the show to send this point home: when Arabella asks if Terry can read her work in her place at the summit, Suzy agrees only after she ascertains that Terry has "the same education, thick and thin" as Arabella, and obviously, that she isn't white. "Write about that," Suzy says to Arabella when she admits she was raped. "Rape! Wonderful," Suzy gleefully declares, when Arabella tells her the direction of her book has changed based on her personal experiences.

By associating Henny House through visual allusion to the Booker organization that underwrites the world's most prestigious literary awards, I May Destroy You makes obvious how central and lucrative immigrant and immigrant descended narratives and experiences are to the contemporary literary industry, while also making clear how this is callously exploitative and doesn't in fact materially impact its most precarious producers in sustainable ways. But, Sheri, you may be thinking, Suzy is Black too, isn't she? Yes. But when Arabella says, "she's not just Black, she's Obama Black" she means that like Obama, Suzy Henny represents an era of late-stage capitalism in which the commodification of racial experience is lucrative not only for lifestyle brands but also for the literary industry. We see this too in the recent establishment of publishing imprints helmed by popular writers such as Phoebe Robinson and Roxane Gay that aim to provide platforms for underrepresented voices.13 It is Suzy Henny who insists on moving ahead with publishing Zain's novel, even after Arabella outs him as a serial rapist at the literary summit. It is Suzy too who publishes his book, after the summit outing, under the benign pseudonym Della Croy-Dickie. What "Obama Black" signals here is an era in which this commodification of identity and often personal trauma is lucrative in multiple industries.

Here's the second digression I mentioned earlier: shortly after the 2020 Olympic Games drew to a close, Jamaican sprint legend Usain Bolt tweeted about how corporate entities that didn't materially support athletes as they trained for the Olympics were now rushing to capitalize on their victories in global competition. "Athletes know your Worth/Power," he warns, "now that they all want to jump onto your Brand/Image for free."14 If you follow Jamaican social media as I do, you know this shade is cast, at least in part, at Adam Stewart, scion of the Sandals Resorts chain among multiple other business, capital, and industrial ventures all over the Caribbean. Once Jamaican sprinters began medaling in Tokyo, Stewart took to Twittercelebrating the victories by announcing, "'The World's Best' deserves 'The World's Best', complimentary vacations when the Olympics is all over."15 This continued as the final races were run and by the end of the competition Stewart had extended the offer of free vacations for medaled athletes from Jamaica to any athlete who medaled at the Olympics from a Caribbean nation.16 Social media influencers quickly took up the excitement of free vacations with videos and posts that not only celebrated Stewart for a brilliant move in civic celebration but also hilariously vied for free vacations themselves. Bolt entered the fray, cooling the tone, with a reminder that this kind of generosity was not extended when athletes needed financial support preparing for the games. He implored onlookers to be skeptical about the ways support comes when athletes are spotlit in the local and international media. Coincidentally, this is also at a time when hoteliers in the Caribbean, because of Covid, are more reliant on local and regional business and goodwill than they have ever been before.17

The literariness of I May Destroy You tells us we have to think about all these things together, because the prestige literary industry is not set apart from other industries that exploitatively commodify the personal for profit. Ultimately, in its conflation of authorial agency with individual mastery and success, I May Destroy You doesn't engage with whether or not the novel as a cultural and aesthetic form is alive and well, but rather asserts that this isn't among the questions that are currently impactful in material and sustainable ways. The final action scene of the series is of Arabella's reading to celebrate the independent publication of her book.

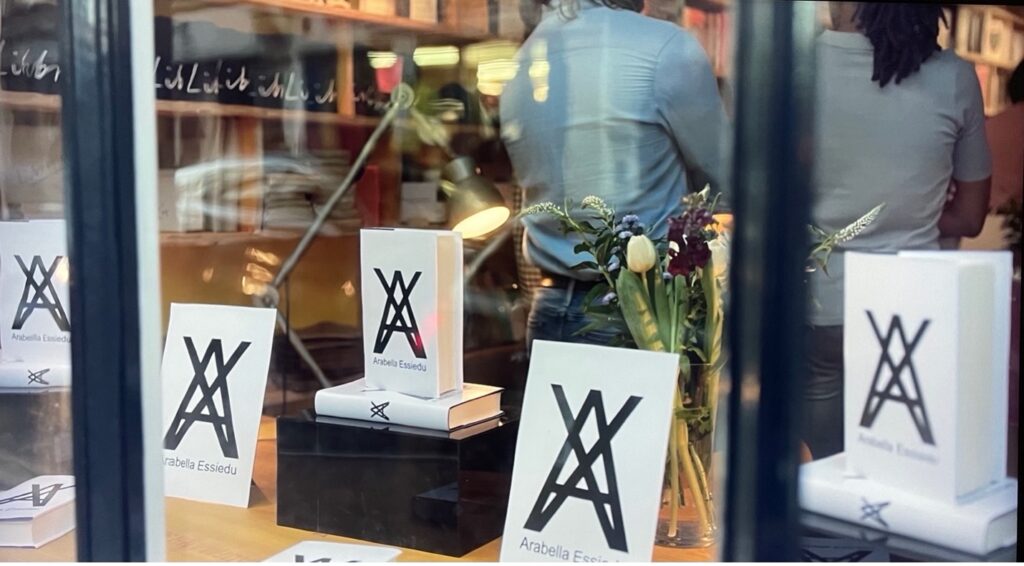

The book's cover is marked with the same diagram she draws in her therapist's office, the letter A with an X on top of it. This is meant to symbolize Arabella's (A) confrontation of the things she has repressed by physically hiding them under her bed (X). X includes the garbage bags that contain the clothes she wore on the night of the rape and a long-forgotten sonogram image from a terminated pregnancy. The convergence of the A and X on the cover of the book that is celebrated in the narrow space of an independent book shop amidst the beaming faces of her adoring fans is the picture of idealized bookishness. It isn't a stretch either to think about these specific letters in terms of the specific Black self-determination and civil rights history associated with the letter X and the gendered and sexual politics associated with the letter A in Hawthorne's The Scarlett Letter.18 And if we still haven't gotten that this show was about writing books, in the actual last scene the word "end" is spelled out in typescript. The show's celebration of idealized bookishness and its glorification of the arduous but eventually successful creation of work has to be understood alongside the fact that it explicitly depicts the literary as no different from other kinds of cultural commodification. The show's major point about literary labor is, thus, that it is no different — and in important ways no less racially stratified — than other kinds of work under capitalism.

Sheri-Marie Harrison is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Missouri, where she researches and teaches Contemporary global anglophone literature, and mass culture of the African Diaspora. She is the author of the book Negotiating Sovereignty in Postcolonial Jamaican Literature (Ohio State University Press, 2014) as well as essays in Modern Fiction Studies, Small Axe, The Journal of West Indian Literature, The Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Contemporaries and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

References

- See Adam Kirsch and Mohsin Hamid, "Are the New 'Golden Age' TV Shows the New Novels?" The New York Times, February 25, 2014; Kelsey McKinney, "Times the Novel Has Been Declared Dead since 1902," Vox, June 17, 2014.[⤒]

- Robert J.C. Young, "Postcolonial Remains," in New Literary History 43, no. 1 (2012): 19-42.[⤒]

- James F. English, The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value (Harvard University Press, 2005).[⤒]

- Akwaeke Emezi, Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir (Diversified Publishing, 2021).[⤒]

- "Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis Say They Don't Believe in Bathing Their Kids or Themselves Too Much - CNN," July 27, 2021. [⤒]

- "Kristen Bell and Dax Shepard Reveal Their Approach to Bathing Their Kids | Complex," August 4, 2021. [⤒]

- Robert H. Shmerling MD, "Showering Daily -- Is It Necessary?" Harvard Health, August 16, 2021.[⤒]

- Lydia Wang, "Is It Really Better For The Environment Not To Bathe?" Refinery29, August 12, 2021.[⤒]

- The Secret Author, "Decline of the English Novel," The Critic, July-August 2020. [⤒]

- Sarah Brouillette, "Aspirational Literary Labor in I May Destroy You," Blindfield: A Journal of Cultural Inquiry, November 11, 2020.[⤒]

- We might also take Brouillette's ideas about "bookishness" to Diletta De Cristofaro's essay in this cluster, which discusses Rory's idealized relationship to books in Gilmore Girls and Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life. Diletta De Cristofaro, "Literary Culture and Achievement Subjectivity from Gilmore Girls to A Year in the Life," Post45: Contemporaries, October 2021.[⤒]

- Zack Sharf, "Michaela Coel Turned Down Netflix's $1 Million Offer for 'I May Destroy You' Over Ownership," IndieWire, July 6, 2020.[⤒]

- "Phoebe Robinson Partners with Dutton/Plume on New Imprint, Tiny Reparations Books," Penguin Random House, July 9, 2020; Elizabeth A. Harris, "Roxane Gay Starts Publishing Imprint With Grove Atlantic," The New York Times, May 26, 2021.[⤒]

- Usain St. Leo Bolt, "A Lot Athletes Sought Support from Cooperate Jamaica in Their Preparation Leading up and Heading to Olympic Games and Got NO HELP. Athletes Know Your Worth/Power Now That They All Want to Jump onto Your Brand/Image for Free," Twitter, August 9, 2021. [⤒]

- Adam Stewart, "'The Worlds Best' Deserves 'The Worlds Best', Complimentary Vacations When the Olympics Is All over for Our Girls! #TeamSandals #TeamJamaica 🇯🇲🇯🇲🇯🇲 Https://T.Co/KEeix5JvAY," Twitter, July 31, 2021.[⤒]

- "Sandals Gifts All Caribbean Olympians Complimentary Vacations," Jamaica Observer, August 9, 2021.[⤒]

- Sandals, for example, is at the forefront of the Covid vaccination campaign in Jamaica, temporarily turning over to the government one property for free, for use as a quarantine site and later as a mass vaccination site. [⤒]

- With gratitude to Sam Thomas who made these additional literary connections. [⤒]