New Literary Television

In January 2020, shortly after the official announcement that Lodge 49 (2018-2019) had been cancelled, I published a short piece on Medium, "Crying Over Lodge 49." I shared it on Twitter and was pleased to receive enthusiastic responses from fans of the show and some of the actors, too. It even elicited a response from the show's creator, Jim Gavin, author of the excellent Middle Men (2013). Gavin retweeted it with the caption: "the high art of low puns." My title was mainly intended to lament the loss of a show I felt was moving and important. I still feel this: over two, ten-episode seasons, Lodge 49 is joyful, poignant, and its ranging critique of capitalism is affecting. However, my Pynchon pun also reinforced the show's titular allusion to The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), a reference Gavin has cautiously embellished, and which, at the least, signals the show's "literariness."

But while there are clear connections between Lodge 49's vision of Long Beach, CA, and Pynchon's California trilogy — Lot 49, Vineland (1990), and Inherent Vice (2009) — Lodge 49 is Pynchonian mostly in that its literary milieu is just as capacious as Pynchon's wildly intertextual worlds. There are other Pynchonian elements to Lodge 49, too. For example, the show's fictional secret society, the Ancient and Benevolent Order of the Lynx might be compared to Pynchon's depictions of subcultural formations like the Trystero or the W.A.S.T.E. system in Lot 49. Equally, aspects of protagonist, Sean "Dud" Dudley (Wyatt Russell), on the surface a sun-soaked surfer drifting into his mid-thirties, are Pynchonian. These elements aside, the literary world of Lodge 49 is distinctive in the diffuse yet deeply embedded, affective, and material roles reading and writing play in its characters' lives. This is a world of local libraries, books on tape, prolific and eccentric genre writers, online poetry workshops, beat reporters who care about story, and celebrity CEO biographies — as well as mystical and alchemical texts. There are allusions to Joyce, Keats and Thoreau, but these appear amidst everyday acts of reading, writing, researching and storytelling that structure and connect characters' lives. These acts offer a refuge from unfulfilling and exploitative labor, the neoliberal culture of competition, and the near-constant threats of redundancy, job loss, and precarity the show's characters face.

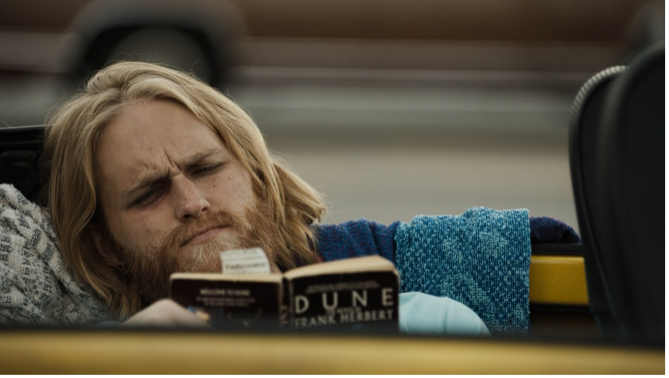

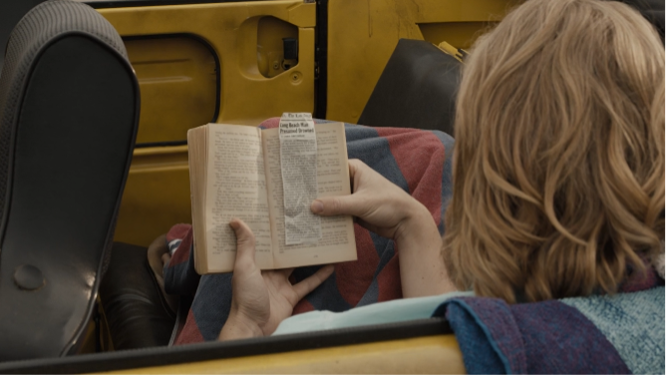

Dud and Ernie Fontaine (Brent Jennings), whose friendship is central to the show (Ernie, a "Luminous Knight," takes Dud on as a "Squire" when he joins the Lynx), are immediately connected to books. In episode one, Ernie reads about Egypt, fantasizing about his "grand tour" — a privilege of becoming "Sovereign Protector" of the lodge. Meanwhile, Dud, homeless and lost, reads Native American Tribes of Southern California, which stokes his disdain for the pressures of modernity. But another scene in the first episode crystalizes Dud's situation. After a night sleeping in his car, he is absorbed in a copy of Frank Herbert's Dune (1964), bookmarked by a newspaper clipping about his father's mysterious drowning. Here, the story of the loss of the father he idolized sits literally between the pages of Herbert's labyrinthine sci-fi saga. This immediately signals the difficulties he is having navigating this catastrophe. Unmoored by loss, homeless because his father's death resulted in the loss of the family pool supply business (and revealed $80,000 of debt), Dud here and throughout the show turns to books for knowledge, healing, and out of boredom.

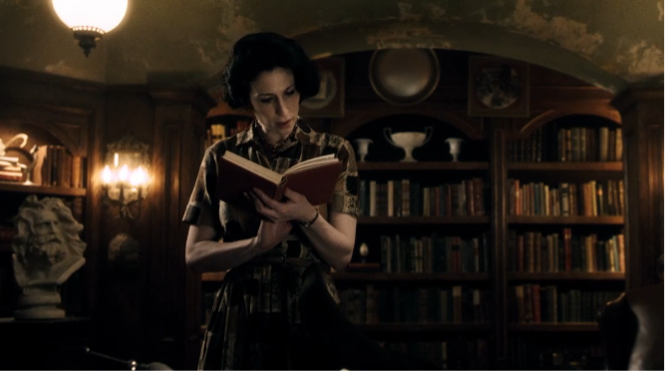

I don't wish to dismiss the alchemical elements of the Lynx, or to ignore the magical realist flourishes of Lodge 49. However, at its heart, the order is about uncomplicated notions of community, connection, and refuge. What Dud intuitively recognizes about the lodge in the first episode, and what Ernie closes the series by emphasizing, is that while life is cold and lonely, "it is different in here" (season one, episode one; season two, episode ten). As Elizabeth Alsop notes in "All Together Now," the lodge becomes a place that engenders "solidarity as a survival strategy," where a group of disparate people are "defined as much by their downward mobility as their devotion to one other."1 I agree with Alsop but wish to also attend to the significance of "the literary" in this vision of solidarity. Even the mystical backstory of Lynx founder, Harwood Fritz Merrill, whose legendary scrolls may contain alchemical secrets (and the bitcoin algorithm) is rooted in the literary. A flashback sequence shows how the bookish passions of Jackie Loomis (Cara Mantella), mother of Sovereign Protector Larry Loomis (Kenneth Welsh), were central to the lodge's evolution and through Jackie, the order's history and the lodge's entanglements with the Orbis aerospace factory come into view. The flashback begins in the lodge's library and suggests a connection between Merrill's and Dud's experiences of crisis. Jackie's interest in lodge lore began as a passion for "getting lost in old books," her favourite a "short biography" of Merrill who founded the order after enduring war and trauma: "a man recovering from a catastrophe who searches and finds a home — I could hold that in my arms" (season two, episode six). In Lodge 49, literary practices help characters navigate crises, but also help them survive the daily grind of contemporary capitalism.

The Workplaces of Lodge 49

Michael Szalay argues that the prestige TV boom beginning in the late '90s responds to deindustrialisation, reproducing a kind of "petrifaction" where "personal and historical events appear simultaneously dynamic and stalled."2 Locating quality TV within the soap opera tradition, Szalay argues that key shows depict the convergence of once separated spheres, the workplace and home: "the world of work and even the historical itself, once juxtaposed to the domestic, disappears into the domestic, such that linear, progressive narratives seem no longer possible."3 In Lodge 49 deindustrialisation is also prominent, particularly via the closure of the Orbis factory. However, it also includes nuanced depictions of the contemporary gig economy, the debt crisis, and the decline in opportunities for fulfilling labor. It even depicts academic precarity when Daphne (Elizabeth Ellis) painfully recalls 12 years of adjuncting: "I've been sleeping on a futon my entire adult life, I've eaten so much ramen my bones are hollow, I once had to do my office hours in a stairwell, and I am $250,000 in debt" (season two, episode four). Though there is some convergence between the workplace and home in Lodge 49 — mostly when characters are sleeping or living at work — the lodge represents a third place: a social space where, as I will show, literary practices engender solidarity. Formally, this difference is registered by the show's slowness, gentleness, and the soft-focussed, sunny haze in which much action occurs. But this is ambiguous, suggesting both warmth and emptiness; Dud memorably describes the "way the light hits you" on a weekday afternoon when unemployed (season one, episode two).

The lives of precarious laborers have long been an interest of Gavin's. In "The Healing Power of Lodge 49," Janelle Okwodu's interview reveals his approach to creating working class characters whose lives are not defined by "weepy struggle." Instead, Gavin (using a central Lodge 49 visual metaphor) emphasizes the lived reality of poverty: "It's just [ . . . ] the water you swim in. You get used to being in debt and getting the short end of things."4 In this way, Lodge 49 draws on some of the ideas, characters and milieu of Middle Men, in which plumbers, sales reps, electricians, drivers and unemployed people live close to the edge. Its laborscape includes three key workplaces: West Coast Super Sales, the plumbing supply company where Ernie (and, eventually Dud) work, the Orbis factory, a cornerstone of the local industrial past, and Omni Capital Food Partners West, owner of the Hooters-style chain restaurant, Shamroxx, where Dud's twin sister Liz (Sonya Cassidy) works; eventually rebranded as "Higher Steaks."

Orbis, a once-thriving aerospace corporation in its final phase of layoffs, is a place "everyone in Long Beach" has connections to (season two, episode one). Dud works there first on a temp assignment putting together redundancy packs and then as a night security guard. In the first role he watches fellow Lynx, Gil (Jimmie Gonzales) receive his severance pack. When Dud tells him he is temping, Gil replies: "smart, temps are the only ones with job security" (season one, episode three). Later in the show, doing his late-night security rounds, Dud discovers a group of ex-Orbis workers meeting in the factory basement socially — first to "break things" and then to "build things." Gil describes the activity to Connie (Linda Eamond) a Lynx and local reporter (fired in episode three) who wants to write about the lives of Orbis workers: "it's just fun building things...if you're not working on a project your thoughts will eat you up" (season one, episode eight).

The importance of meaningful labor that is not alienating — alongside the struggle for survival — also characterizes the portrayal of Liz. Just as important as Dud or Ernie to the larger narrative, Liz's experience of dealing with loss, plus the crushing debt and role of "responsible sibling" she is saddled with, is powerful; and Cassidy's performance as a smart, cynical, and also sentimental character, is extraordinary. Liz's story begins at Shamroxxx, where she works for tips because the bank is garnishing her wages. Eventually, she enrols on a corporate recruitment program and at an executive training event she monologues on Shamroxxx: "yeah we have the 'three Cs', plus all the TVs and the fried food. The main thing of course [ . . . ] is the tits. But if we're going to ask ourselves what's underneath the tits and everything else, I'd have to say: loneliness and despair" (season one, episode eight).

Similarly, Ernie, a Navy veteran approaching 60, lives paycheck to paycheck and gambles to supplement his dwindling commissions at West Coast Super Sales, where he is outdone by younger reps like Beautiful Jeff (Michael Lee Kimel). For Ernie and almost every character, work is never fulfilling; and everyone is struggling to pay the bills except the executives operating in a "moral grey area" (season one, episode nine). The 2008-2011 financial crash looms large over these stories of struggle. For example, we learn that before the crash Ernie could "write business all day," but that now it is "all just a hustle" (season one, episode two). Yet despite this bleak landscape, there is always a sympathetic ear and a beer waiting at the lodge.

Because of the show's hazy, sun-drenched aesthetic — which often evokes a lack of clarity or vision — it is tempting to read Lodge 49 as a dramatization of Lauren Berlant's logic in Cruel Optimism (2011). Indeed, Berlant's diagnosis of a persistent belief in notions of "the good life" which "for so many is a bad life that wears out the subjects who nonetheless, and at the same time find their conditions of possibility within it," undoubtedly provides insight here.5 In one episode, Ernie, a pragmatist is encouraged by his boss, Bob (Brian Doyle-Murray) to be positive when things aren't going well. Bob tells Ernie to repeat the mantra, "life is good" which he briefly embraces. Later in the episode, Blaise (David Paquesi), the lodge member most invested in its alchemical tenets, declares that "anything is possible" and Dud combines these sentiments, enthusing that: "anything is possible and life is good!" (season two, episode two). But Ernie and Blaise are confronted with devastating truths and Dud's rarely-shaken optimism flies in the face of reality.

Dud's disposition is inherited from his father and in an argument with Liz, who is concerned about this optimism, he claims their father was happy, and "knew how to enjoy life" (season one, episode three). Liz counters with the stinging riposte that "he was faking it," that his "debt was crushing him," and that his drowning was actually suicide. Such moments of reckoning cut through fantasies of the good life. Dud, Liz, and Ernie all break down and rely on each other to keep going; eventually they confront hard realities and find solace through solidarity. Before the joyful final two episodes, Ernie has a revelation which comes to him via the Tom Stone novels he and Dud have bonded over, written by the enigmatic, Lamar Marvin Metz (Paul Giamatti). Ernie realises life is a "zugzwang," a chess scenario where one is forced into a perilous move: "You know what, it's beautiful. Guys like us, it doesn't matter if we make the smart choice or the stupid choice. We'll wind up worse off anyway. we might as well embrace the zugzwang" (season two, episode seven). Here, a realistic (and fatalistic) optimism is retained — one that feels grounded, sincere and aware — and it appears through this odd literary allusion.6

Literary Connections

Much prestige TV has utilized literary allusion during what Philip Maciak has described as "the era of television's grasping for legitimacy."7 These allusions have sometimes had narrative functions or thematic resonance, but usually have been deployed to imbue shows with cultural capital, presuming deferentially that the novel is "an eternal ark of prestige and cultural value that elevates anything it touches and television is a medium sorely in need of the novel's authorizing aura."8 I am not seeking to locate Lodge 49 in relation to debates about televisual novels and novels for television. I am simply showing how, in Lodge 49, eclectic patterns of allusion and acts of reading and writing are at the heart of how characters relate to each other and make sense of the world.

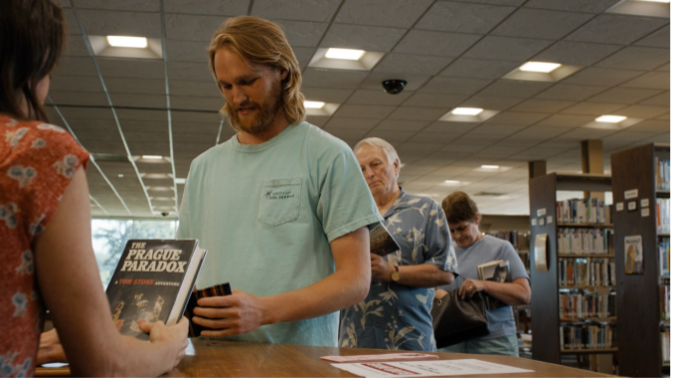

Dud and Ernie bond over Metz's Tom Stone novels and in a late plot development, they meet Metz who, it transpires, is a Lynx; he even reveals that his books are "sprinkled with Lynxian references" (season two, episode seven). As intriguing as this three-episode cameo is, and as much as the images of Metz hauling around his typewriter add to the show's literary milieu, what is important is the way Dud and Ernie share their experience of reading Metz. They go to a book signing event and his storytelling is part of the fabric of their days, driving around Long Beach. They read or listen to his books in nearly every episode and at certain points his writing, cartoonish as it is, informs their actions. As season one culminates, and Ernie's personal life becomes increasingly overwhelming, he listens to the following lines from The Prague Paradox: "Everything he'd been through in the last eight weeks, the microfiche, the sixteen kills, the virus that was now living inside his body, was hurtling with him as he double-clutched around a corner and the Vltava River swung into view. There, glittering on the far shore like fool's gold was Zbraslav, the place where this would all end" (season one, episode nine). Ernie has actually just pulled up outside the lodge, but he is in a predicament and in a strange way Metz's prose gives him ballast. Later, as Dud and Ernie begin to feel they are being tricked by the elusive Captain (Bruce Campbell), Ernie recalls: "it feels like what happened to Stone in Luxembourg: he got set up, fell into a trap" (season one, episode nine). And, of course, Ernie's "zugzwang" epiphany, central to the larger ideas behind the series, is straight from Metz.

When Connie meets Metz at the lodge, she dismisses him as "the author of those horrible thrillers" but ultimately breaks her writer's block via Metz's advice to use a pen name (Metz had said that women are sometimes alienated by his "muscular style" so he writes erotic romance novels under a pen name.) Connie's story is critical to my argument. Fired from her job as a local reporter, entangled in a difficult love triangle and facing a life-threatening condition, she finds a way to survive by writing about the lodge and about Long Beach. Her story is a quest for meaning and purpose and she finds this through writing. One of the show's most satisfying character conclusions is Connie "clacking away" on an old typewriter in a secret annex of the lodge library.

That this happens in the lodge library and, indeed, that the lodge has a library, is obviously important. It is a secret library discovered by Dud, an occurrence that coincides with the notion espoused by Blaise that, through Dud, the lodge is "waking up" (season one, episode three). Moreover, it is repeatedly identified as a place of imagination and thought that resists the trappings of capitalist modernity. When Jocelyn (Adam Godley), a Lynx emissary from London, describes it as "an asset," that might mitigate the lodge's debts, Blaise is horrified: "it's not an asset, it's a citadel to knowledge" (season one, episode eight). It is certainly a place of connection where characters repeatedly share moments of intimacy and friendship in front of a backdrop of books. In one such scene, Dud invites Emily (Haily Wist), the local public librarian to look around out of professional interest and they have a charged and poetic conversation which reinforces - if nothing else - the importance of libraries.

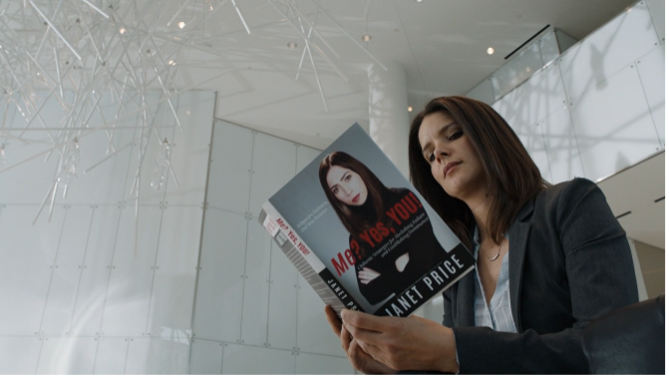

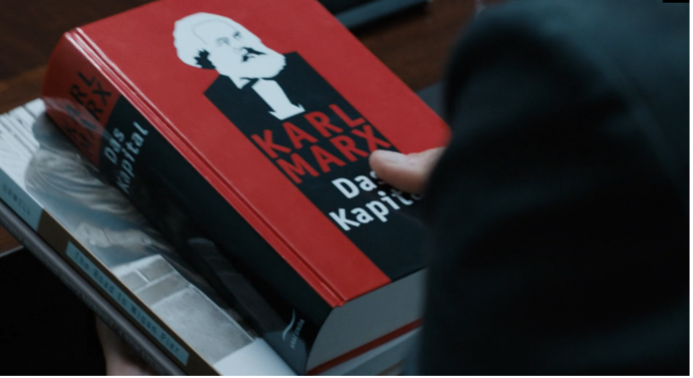

Dud's bookishness is a defining if initially surprising trait. He is a comically easy-going surfer, but not a stoner or slacker and is always seen with a book in hand: from Dune (1964) to Francis Yates' Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964). Other characters are surprisingly literary, too. Ernie's elderly boss, Bob, enrolls in an online poetry workshop and writes poems for co-workers which are comically bad but affecting as Patterson-esque pretence-less, acts of everyday creativity. On hiring a new employee for the order desk, he notes: "like Emerson wrote to Whitman — I greet you at the beginning of a great career" (season two, episode four). Multiple literary encounters are woven into Liz's story too and her first experiences at the Omni offices are oddly defined by books. Waiting for her interview she curiously thumbs through a copy of CEO Janet Price's (Olivia Sandoval), Me? Yes You: Strategies for Abolishing Failure and Establishing Dominance and then looks through a stack of books in Eugene Mar's (Hayden Szeto) office, which include Marx's Capital (1867) and George Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier (1938) (season one, episode seven). These anti-capitalist books are conspicuous in their incongruity at Omni and another way in which Lodge 49 pits books against (but also as proponents of) capital.

The literary conceits of Lodge 49 do not mean it isn't a televisual wonder. Its central visual metaphors of swimming pools (staying afloat or floating by) and doors (transition) are potent and often beautifully rendered. My emphasis on its ordinary literary world is also not intended as a rejoinder to Jason Mittell's argument that "cross-media comparisons obscure rather than reveal the specificities of television's storytelling form."9 I simply want to celebrate the possibilities of a world where books, storytelling, and writing are generative and restorative for all kinds of people: a world that incites Jocelyn, leaving the lodge forever, to quote Ford Madox Ford to the surf-guitarist Lynx, Don Fab (Dick Dale): "isn't there any heaven where old beautiful dances, old beautiful intimacies, prolong themselves?"

A final note. Lodge 49 has taken on an intriguing literary afterlife with the establishment of Gavin's new press, Tiger Van Books — a reference to a van driven by Lodge 49's El Confidente (Cheech Marin). The Tiger Van website describes its belief in books and asserts that its "business model is failure".10 The press's first novel, just released, is Shaky Town by Lou Matthews, whom Gavin describes as a major inspiration for the show.

Arin Keeble (@KeebleArin) is Lecturer in Contemporary Literature and Culture at Edinburgh Napier University. His research interests include the literary and cultural representation of terrorism and crisis, neoliberalism and systemic violence, and punk culture. He is the author of Narratives of Hurricane Katrina in Context (2019) and various journal articles and book chapters.

References

- Elizabeth Alsop, "All Together Now," Film Quarterly: Quorum, August 20, 2020. [⤒]

- Michael Szalay, "Melodrama and Narrative Stagnation in Quality TV," Theory and Event 22, no. 2 (2019): 469. [⤒]

- Szalay, "Melodrama," 470. [⤒]

- Michelle Okwodu, "The Healing Powers of Lodge 49," Vogue, May 28, 2021.[⤒]

- Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Chapel Hill, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 27. [⤒]

- The "zugzwang" is also a key metaphor and plot device in Michael Chabon's The Yiddish Policeman's Union (2007).[⤒]

- Philip Maciak, "The Televisual Novel," in American Literature in Transition: 2000-2010, edited by Rachel Greenwald Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 88. [⤒]

- Maciak, "Televisual," 88. [⤒]

- Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Televisual Storytelling (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 18. [⤒]

- "Manifesto," Tiger Van Books, accessed October 19, 2021.[⤒]