Abortion Now, Abortion Forever

In her 1991 film S'Aline's Solution, the American artist Aline Mare narrates her personal abortion story.1 Integrated into video that captures Mare's abortion process is a repeated voice-over conjugation of the verb "to choose":2

I choose, I chose, I have chosen.

In the context of abortion rhetoric in the United States, "choice" plays as a kind of soundtrack — the background vocals, a voice over on loop. Yet as Mary Poovey argued in 1992 about the language of rights, the rhetoric of choice "enacts its price."3 As a number of thinkers have noted, the fantasy of choice runs up against many limitations: it is a "politically conservative concept" that deemphasizes collective women's rights and "primarily resonates with those who feel they can make choices in other areas of their lives";4 it "invert[s] effortlessly into [its] opposite" through its binary logic and relationship to the argument of fetal personhood;5 it centers individualism and slides easily into the frameworks of racial capitalism and neoliberalism; it focuses on the individual instead of the structural; it "reproduces a heteronormative universe"6 that expects everyone to adhere to its dictates. To make a choice. To choose.7

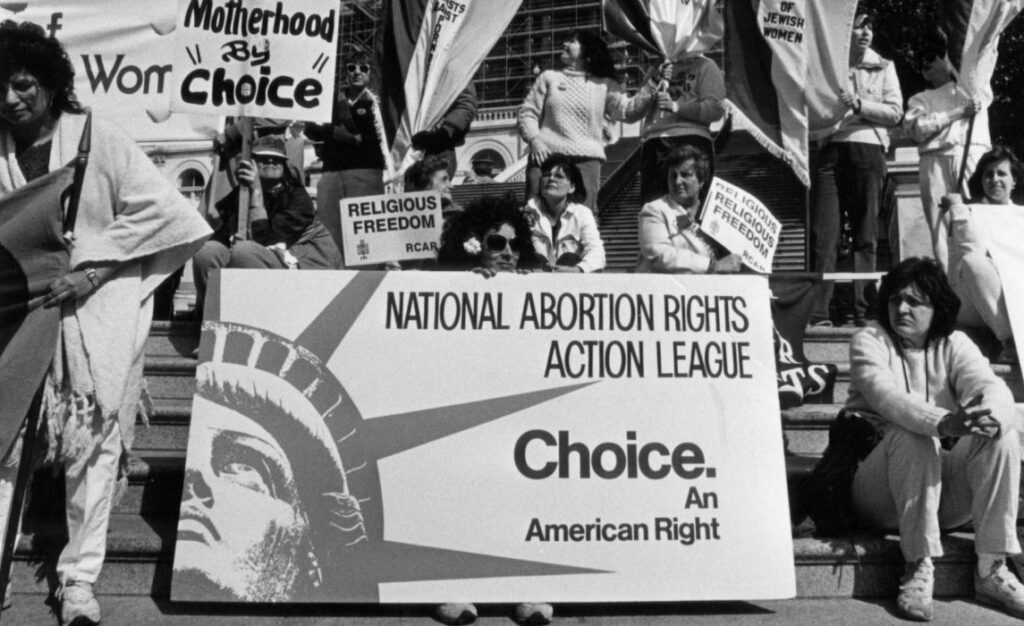

In the twentieth century, the framework of "choice" was foundational to the struggle to procure and protect access to abortion in the United States. Hedging the fight against pro-life advocates — "pro-choice" perhaps a less bitter pill than "pro-abortion" — early campaigns in the 1970s connected abortion choice to Americanness itself. For example, during the mid-1970s, the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL) commissioned posters featuring the face of the Statue of Liberty, shot from below as if to emphasize its power, anchored by slogans like "Choice. An American Right" and "I'm Pro-Choice . . . and I Vote."8

The photograph of the NARAL rally that centers the abortion choice poster is of particular interest in its conflation of religious choice and reproductive freedom, staged through the photograph's central image of the Statue of Liberty, which funnels out into different concepts and categories — motherhood by choice, religious freedom, advocates for Jewish women — all held underneath the larger umbrella of an "American right."

The legacy of this abortion rhetoric has shaped public policy and epistemology around reproduction in the United States and participated in the work of nationalism. By linking abortion access to foundational aspects of American identity and civic life, such rhetoric conflates metonymic associations — liberty, power, autonomy, individualism, decision-making, political action, and even patriotism — with the ability to decide whether to carry a pregnancy to term. In effect, these conflations intermix operations by which a body relates to the community, the state, and the larger world with those by which a body relates to what is inside it and what it is able to do.

Recasting the private spaces of the body as politicized public space, these associations reframe the body as a productive site for nationalism. By separating the legal question of abortion from the broader matrix of reproductive health, they also position abortion as a (distinct) question of bodily privacy and autonomy, effacing the longstanding relationship between abortion, contraception, and reproduction.9

Yet paradoxically, increasingly stringent regulations on abortion create the conditions for broader restrictions of the larger matrix of reproductive and gender-affirming care precisely because abortion's material remedies, including herbal abortifacients, traverse such artificial boundaries. Recognizing abortion's entanglement with this care — an entanglement that has been understood in deep history but effaced by recent U.S. legal policy and politics despite many connections at the level of medications, procedures, and access — is crucial for both practice and activism.

In contemporary activist discourse, new frameworks have emerged that question the capitalist and individualist underpinnings of choice by emphasizing relationality instead. For example, a 2021 blog post from Planned Parenthood argues that "we need to go beyond choice language to affirm our support for abortion," suggesting that activists focus their efforts on structures rather than individuals.10

We find this moving beyond — this telling of a different story — in the work of contemporary artist Lena Chen. In a participatory performance piece, We Lived in the Gaps Between the Stories,11 Chen brings into public view the relationship between people who hold deep knowledge of herbal abortifacients and the material reality of the plants themselves. We Lived combines spoken abortion stories with knowledge-sharing workshops, music, and visual installations that draw on the feminized practices of writing thank-you notes and making wreaths.

Displayed on museum walls and gathered into centerpieces of her ritualistic procession, Chen's plants suggest the importance of community-based knowledge channels. Combining the textual and the visual, the linguistic and the performative, We Lived thus constructs a counternarrative to the dominant rhetoric of choice. Resisting ongoing efforts to institutionalize and medicalize the practice of abortion, Chen's work visualizes the way abortion can exist — and has always existed — in extra-institutionalized, relational contexts.

As Chen's work suggests, herbal remedies have been used for reproductive management for millennia, although fully tracing such contexts is necessarily complex. Ancient authors writing in Greek and Latin mention abortion and abortifacient plants, including yarrow, safflower, mint, broom, pennyroyal and silphium, that might be used as contraceptives and abortifacients.12 While the circulation of this plant knowledge beyond civic oversight has been a defining aspect of human experience, its exploration as a form of resistance in the context of chattel slavery has been especially critical.

Examining the early modern period, scholars have theorized that enslaved people shared abortifacient knowledge as a form of resistance to colonialism, slavery, and forced reproduction.13 For example, Jennifer L. Morgan traces the path that abortifacient knowledge traveled from Africa to the Americas,14 and Londa Schiebinger finds a similar history of knowledge shared between the Tainos and Arawaks and enslaved people from Africa arriving in the Americas.15While Chen's work does not directly engage with these specific histories, their implicit presence haunts multiple dimensions of her piece.16

Charting continuities between the past and the present, Chen's work with abortifacients and emmenagogues17 (re)imagines reproductive management through an alignment with plant life and offers an alternative view of ancient and modern abortion care as communal knowledge-sharing and collective practice. Laced through various parts of the artwork are visually striking plants, including yarrow, safflower, mountain and lemon mint, and scotch broom — plants used for reproductive management. These plants engage a history of remedies that work along a spectrum from contraception to abortifacient determined by varied combinations and dosages. Such calibrations, like the community workshops that accompany Chen's performance, might be shared person to person to operate outside the reach of the growing state-sanctioned incursions on reproductive rights that first targeted abortion.

We Lived's performance history responds directly to one incursion, the leaked Dobbs decision of 2022. After initially producing the work in 2021 for the artist-run Wave Pool Gallery in Cincinnati, Ohio, Chen reworked it following the leak.18 In its original context, the piece already engaged the fraught history of precarious access to abortion, but its later iteration in Manhattan's Tompkins Square Park responded directly to the specific impact of the decision. The second version also brought Chen and her collaborators into community with other writers and artists making work in protest — in a spirit similar even to this cluster of work on Post45 that marks the one-year anniversary of Dobbs.

In each iteration, Chen's work highlights the plants themselves. In the gallery in Cincinnati, vases installed on the wall hold flowering contraceptives and abortifacients as well as two plants without such properties, gomphrena and hydrangea. This combination suggests ways in which plant-based abortifacients and contraceptives might move through the world as garlands and wreaths, "mingled with all kinds of colors,"19 woven together with other plants and passed easily and without oversight. Chen's performance work — both in Cincinnati and Manhattan — features such wreaths, ranging from those comfortably held in the hand to a much larger, central wreath, the performance's focal point that requires at least two people to bear.

During the procession in Cincinnati — captured on video and shared on Chen's website for the work — participants walk through public streets accompanied by a violinist and an amplifying sound system towed in a wagon. As they walk, their wreaths encircle small glimpses of the cityscape: a stretch of asphalt road, a painted green municipal trash can, the grate of a closed storefront, a beige wall of a high-rise, a brightly colored geometric mural, lines of a crosswalk, bricks of a wall, trees in the park, and fragments of the participants' own smiles, gazes, and bodies. All of these glimpses, these framed yet fleeting moments, become the backdrop for Chen's ritual. The film highlights parts of the procession and focuses on different flowers, invoking temporal continuity even as the event itself remains bounded by time and resistant to complete documentation.

The film layers Chen's even voice reading a continuous narrative that begins not in Mare's first-person but instead in second:

you wrote a high school paper against abortion and got an A on it / . . . you grew up Catholic in a town where an abortion provider was murdered / . . . You were the homecoming queen / you were a middle school teacher / you studied psychology / . . . you got pregnant while married and on birth control / you got an abortion you didn't regret . . . when you were 14 your best friend found out she was pregnant during gym class

Chen's complex use of second person enfolds the possibilities of either a singular or plural — and beyond, as "you" can represent a transposition of the I/author, a choose-your-own-adventure version of the reader, a completely hypothetical person outside of any known actor, and most especially the slippage between all listed options and more yet unknown. By foregrounding this slippage while also retaining experiences of individuality, Chen models a relational balance of individual, communal, and even herbal actants. Her piece thus reaches beyond the small cohort of its visible participants to enfold its wider audience.

After this series of vignettes, the point of view shifts from those receiving abortion care to those offering it. No change in tone marks the seamless transition:

You book appointments / you explain state laws / . . . you perform ultrasounds / . . . you make sure that people are safe at home / . . . you raise money so people can afford to have a choice / . . . you hold hair / . . . you bear witness

Here again, Chen mobilizes the second person to similar effect. Her sentences and their measured, connected intonation highlight the range of experiences of providers from administrative to technical to emotional. The weaving of these vignettes that reiterate single sentences in the second person emphasizes the intersections among pregnancy, intimate partner violence, state and religious-incited violence, and abortion care. Such intersections become legible only within a larger network made possible by human interconnection as well as human connection to plant life.

Embracing a relational futurity, Chen moves toward resolution by thinking through time, welcoming humanity and all of its entanglements, and liberating abortion subjects and verbs from potential stasis:

your love of humanity will continue to carry us forward / you are our past, present, and future

Thus in Chen's vision, the "I" — that centerpiece of choice rhetoric, that sovereign/subject-oriented framework: I choose, I chose, I have chosen — has been situated within a network of relationality. This network preserves difference and the many distinct stories of individuals while it also demonstrates both interdependence (the "you" whose love will carry the "us") and promise for a future towards which we can continue to move.

In light of the current deepening assault on abortion in the U.S. and many other countries at the time of this writing, we believe it is imperative to consider the limitations of the framework of choice. Artists and thinkers like Chen help us trace what has been misnamed as choice, refusing its limitations in favor of multiple continuities — among the past and the present, among plants and humans, and among human communities and their networks — forged within and beyond institutions and shaped by strategies of sharing.

Acknowledgments: For help with the ideas in this piece and its longer version — including sharing pre-published work and offering comments, assistance, and inspiration — we extend our heartfelt thanks to Paul Delnero, Jena DiMaggio, Lael Ensor-Bennett, Gloria Fisk, Mary Fissell, Hilary Gallito, Hsuan Hsu, Tobias Menely, Andres Reyes, Margaret Ronda, Jeannette Schollaert, Caroline Schopp, Tyler A. Tennant, Mack Zalin, Michael Ziser, and our panel presenters at the April 2023 Association for Art History conference (for which we convened a double session on Art and Abortion): Johanna Gosse, Abigail Haak, Hana Janeckova, Elizabeth Legge, Allison Morehead, Márcia Oliveira, Caitlin Powell, and Maryanne Saunders.

Leila Easa is an instructor of English at San Diego City College; a PhD student in English at the University of California, Davis; and a 2022-23 Mellon/ACLS Faculty Fellow.

Jennifer Stager is an assistant professor in the Department of History of Art at Johns Hopkins. She is the author of Seeing Color in Classical Art (2022).

Together they are the authors of Public Feminism in Times of Crisis: From Sappho's Fragments to Viral Hashtags (2022) and "Overwriting the Monument Tradition" (RES 2021). Their thinking in this Post45 essay was inspired in part by the double session on Art & Abortion they convened at the Association for Art History conference in April 2023.

References

- We first learned about Mare's work in Jennifer Doyle's essay "Blind Spots and Failed Performance," in which Doyle reads Mare through Valerie Hartouni's engagement with Mare's video. See Jennifer Doyle, "Blind Spots and Failed Performance: Abortion, Feminism, and Queer Theory," Qui Parle 18(2009): 25-52.[⤒]

- Aline Mare, "Early Works," AlineMare.com. Accessed 2 May 2, 2023. https://www.alinemare.com/early-works/project-two-kyd6d.[⤒]

- Mary Poovey, "The Abortion Question and the Death of Man." Feminists Theorize the Political, edited by Judith Butler and Joan Wallach Scott (Routledge, 1992), 252-261; 241.[⤒]

- Marlene Fried, quoted in Loretta Ross, "Understanding Reproductive Justice." Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, edited by Carole R. McCann (Routledge, 2021), 77-82; 81. This work builds from the earlier Reproductive Justice by Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger (University of California Press, 2017).[⤒]

- Poovey, "The Abortion Question," 249; 250.[⤒]

- Doyle here is reading Lee Edelman's No Future. See Doyle, "Blind Spots," 30.[⤒]

- Despite the skepticism with which we approach choice, we affirm our commitment to this essential premise: unquestioning support for universal access to abortion and all other forms of reproductive and family care.[⤒]

- "1969-2019: The Fight for Our Lives." National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws/NARAL Pro-Choice America. Accessed 2 May 2023. https://www.prochoiceamerica.org/timeline.[⤒]

- This making public of private space of the body is particularly ironic in light of Roe's emphasis on privacy. In the majority opinion authored by Justice Blackmun in Roe vs. Wade, "the court declared the abortion statutes void as vague and overbroadly infringing those plaintiffs' Ninth and Fourteenth Amendment rights." Specifically, "State criminal abortion laws . . . violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects against state action the right to privacy, including a woman's qualified right to terminate her pregnancy." Roe v. Wade. 410 US 113. Supreme Court of the US, 1973, Library of Congress, 113-114. [⤒]

- "What's Wrong with Choice?: Why We Need to Go beyond Choice Language When We're Talking about Abortion." Planned Parenthood Advocacy Fund of Massachusetts, Inc., February 10, 2021, https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/planned-parenthood-advocacy-fund-massachusetts-inc/blog/whats-wrong-with-choice-why-we-need-to-go-beyond-choice-language-when-were-talking-about-abortion. [⤒]

- An allusion to Margaret Atwood's 1985 The Handmaid's Tale, Chen's title, We Lived in the Gaps Between the Stories, invokes the larger complex of nationalist patriarchal control over reproduction. Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale (Ballantine Books, 1985.[⤒]

- On ancient writers and abortion, see Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants; Hippocratic Corpus, Disease and Diseases of Women; Pliny the Elder, Natural History; Vergil, Georgics; Galen, Hygiene and On Natural Faculties. [⤒]

- These claims draw heavily from Barbara Bush-Slimani's 1993 argument "Hard Labour: Women, Childbirth and Resistance in British Caribbean Slave Societies," History Workshop Journal 36 (1993): 83-99; this set the groundwork for theories of resistance among enslaved populations that have been developed more recently in work including Jennifer L. Morgan's 2021 Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic (Duke University Press, 2021), which demonstrates racial capitalism's foundational reliance on forced kinship relationships produced by chattel slavery; Mary Fissell's Long Before Roe (forthcoming; Seal Books 2025), which highlights the "unequal relations of power" that often structured "knowledge exchange about New World abortifacient plants"; and Tracey Rose Peyton's 2023 novel, Night Wherever We Go (Harper Collins, 2023), which dramatizes such reproductive resistance through the lives of her main characters, six enslaved women.[⤒]

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 113.[⤒]

- Londa Schiebinger, "Agnotology and Exotic Abortifacients: The Cultural Production of Ignorance in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 149, no. 3 (2005): 342. See also Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Harvard University Press, 2004).[⤒]

- The relationship between abortifacients, emmenagogues, and contraceptives that Chen's work traces has important implications for reading abortion back into the archive despite its sometimes vexed omissions. For example, in the ancient Mediterranean, Theophrastus describes hellebore, dittany, and silphium without explicitly naming their abortifacient capacities, instead sharing their possible roles in managing miscarriage or difficult labor and purging the body more generally (Enquiry into Plants IX.ix.2, IX.xvi.1, VI.iii.1-2). Such textual references may obscure the possibilities of a plant's use as an abortifacient — or at least remain silent on the topic. As analyzed above, scholars working on later histories of abortifacients invite us to read into such silences — and in them, to locate possibility.[⤒]

- Emmenagogues, from the ancient Greek emmēna (menses) and agōgos (drawing forth), are herbs that stimulate menstruation. "emmenagogue, adj. and n.". OED Online. March 2023. Oxford University Press.[⤒]

- Chen's residency and performance included workshops led by herbalist Ellie Mae Mitchell, florist Patricia Campos, growers Village General and Camp Washington Urban Farm, and chef Madeline Ndambakuwa. For the initial performance, see Wave Pool Gallery (https://www.wavepoolgallery.org/we-lived-in-the-gaps-1) and Lena Chen (https://www.lenachen.com/we-lived-in-the-gaps-between-the-stories/). On the post-Dobbs performance, see Shanti Escalante-De Mattei, "Artists and Activists Banded Together to Tell Abortion Stories at an Impassioned New York Event," ArtNews, May 9, 2022, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/abortion-stories-cassandra-neyenesch-lena-chen-1234628089.[⤒]

- Sappho, Fragment 152 (Sappho and Anne Carson, If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, translated by Anne Carson, Alfred A. Knopf, 2002). [⤒]