Stuckness

When I started writing this, in mid-June of 2022, it was 100 degrees in central Illinois. A "heat dome" had settled over much of the United States — it was stuck there, heating up the country. Similar waves were driving record temperatures across Europe and the Middle East, and earlier in the spring India and Pakistan had suffered temperatures well over one-hundred degrees for weeks on end, prompting fears that the opening scenario of Kim Stanley Robinson's cli-fi novel The Ministry for the Future — in which a heat wave in India kills twenty million people — was becoming a reality.1 Meanwhile, birds were literally falling from the sky in Spain, cows were dropping dead of the heat in Kansas, wildfires and floods were raging, and — in a distinct yet related apocalyptic register — Vladimir Putin was threatening to kill us all with nuclear weapons.2

This confluence of horrors — the novel weather conditions of a warming world, the resurgent threat of nuclear annihilation — only intensified in the ensuing months. To register this worsening situation, in January 2023 the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists pushed their iconic "Doomsday Clock" ten seconds forward to ninety seconds to midnight. The Bulletin, a media outlet founded by Manhattan Project scientists in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, began with the primary objective of alerting readers to the dangers of nuclear war, but over the years it has expanded its scope to include other threats like "disruptive technologies" and, of course, climate change. The image of the clock — which first appeared in 1947, on the first cover of the Bulletin when it became a magazine — is meant to convey the severity of these threats, marking in terms of minutes and seconds our proximity to destruction. Initially set at seven minutes to midnight, the clock's hands have been reset 25 times as of this writing, from seventeen minutes to midnight at the end of the Cold War to ninety seconds today, "the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been."3

![[Alt-Text: Black and white illustration of the last quarter-hour of a clock, with the hands set at 90 seconds to midnight.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/barn-1.png)

The graphic designer Michael Bierut has called the Doomsday Clock "the most powerful piece of information design of the twentieth century," and its power lies not only in its emphasis on the scale and imminence of these planetary threats, but also in how it reveals our stuckness.4 Though it has moved many times the clock has not moved very much. Seventeen minutes to the apocalypse is not much more reassuring than five minutes, and it's worth noting that perhaps the closest we've ever come to nuclear annihilation was in 1995 — four years after the Cold War supposedly ended, with the clock at a seemingly comfortable fourteen minutes to midnight — when Russian air defenses mistook a Norwegian scientific rocket for a submarine-launched ballistic missile, setting in motion what was nearly a retaliatory response against NATO. A similar thing had happened in 1983, when a Soviet satellite erroneously reported inbound U.S. ICBMs, creating a scenario not unlike the one depicted in the movie War Games, which had (a little uncannily) been released three months before the Soviet false alarm.5 In both of these cases, decisions in which, quite literally, the lives of billions and the future prospects of life on earth hung in the balance, had to be made in less than twenty minutes, within the timeframe of the hands of the Doomsday Clock. Putin's recent nuclear brinksmanship has amounted merely to reminding us that the threat is still here, that even as the Cold War fades to a distant memory we remain stuck in the time of that clock, waking up every day in a world not just figuratively, but literally twenty minutes from total destruction.

Our acclimation to this threat would be pretty well captured by this dog meme:6

So would our acclimation to climate change. In both cases the meme could be read more or less literally: the immediate and fiery threat of nuclear annihilation; the slow burning of a planet increasingly literally on fire. These conditions are not fine, but what the meme captures so well is something like what ecologists and earth scientists call "shifting baseline syndrome," which is a fancy way of saying we get used to it.7 Readers of the future will hardly blink at the meteorological facts and figures I laid out in the opening paragraph of this essay, but the meme will still be applicable — it will just refer to a far worse set of facts.

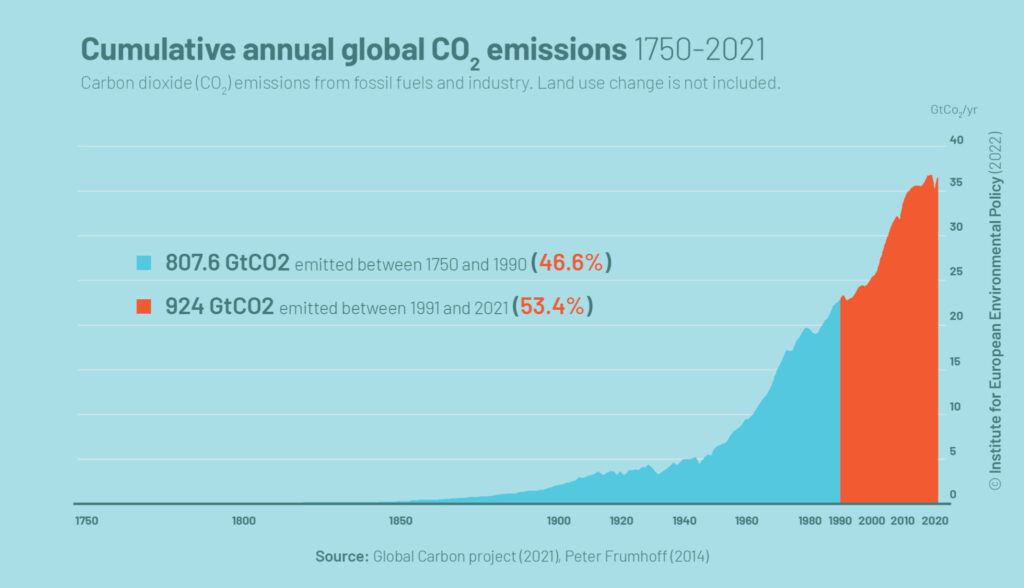

That opening paragraph, by the way, is a pretty good example of what Heather Houser calls the "Catalog of Despair," one of three pervasive "tics" she identifies in contemporary American climate writing.8 Houser identifies these tics not to criticize climate writers for a lack of originality, but to emphasize their stuckness. These writers find themselves stuck saying the same thing over and over, as the US and the world's other major emitters fail to respond adequately to an obvious, well-understood, and existential threat that is only getting worse. The worsening trajectory is readily apparent to anyone who can read a graph, and its implications for the planet have been clear for over a century.9 The basic science of global warming has been understood at least since 1896 — when Svante Arrhenius published his paper "On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground" — and it has been a feature of mainstream political discourse since at least 1988, when the climate scientist James Hansen testified in a US Senate hearing that the "greenhouse effect has been detected and is changing our climate now."10 Since that announcement, popular books by writers like Bill McKibben, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Hansen himself have proliferated, along with no fewer than six reports from the International Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), each more alarming than the last. Everyone understands both the problem and the solution, so there's little new to be said, leaving climate writers stuck in a rut, producing only an ever-intensifying catalog of despair and disaster.

Despite this proliferation of disturbing information, since Hansen's declaration the world's major economies have emitted more CO2 than they did in all of history prior to 1988.11 An alien from another planet might ask how, exactly, it could be possible that the supposed standard-bearers for enlightenment rationality would respond to the unambiguous announcement of the threat of CO2 emissions by literally doubling those emissions — and it would be a good question! Kolbert, who is from this planet, did in fact raise this point in her 2006 book Field Notes from a Catastrophe. "It may seem impossible to imagine," she wrote by way of conclusion, "that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself, but that is what we are now in the process of doing."12 But it may be less impossible to imagine if we keep in mind that this advanced society had already acclimated itself to the ongoing daily threat of nuclear annihilation. And the persistence of these unimaginable realities ultimately reveals precisely the opposite: that it is apparently impossible to imagine not living under these conditions, impossible to imagine a future beyond carbon emissions and the nuclear threat.

It is typical in academic discourse to describe this as a failure of imagination. But this imaginative problem is also an infrastructural one. As Akhil Gupta has put it, "infrastructures are concrete instantiations of visions of the future," but those material infrastructures long outlast whatever rationale or mandate they may have had at the moment of their conception.13 Writing for Time Magazine two weeks after the US Army Air Force destroyed Hiroshima with an atomic bomb, James Agee announced that "in an instant, without warning, the present had become the unthinkable future."14 That future, as we know, would be the future of nuclear terror, materially instantiated in what Jessica Hurley has called the "infrastructures of apocalypse," from toxic sites of uranium extraction and nuclear waste to the global network of silos and airbases and submarines that would eventually maintain a force, at the height of the Cold War, of 20 to 30 thousand weapons in the US alone.15

Since that height, the American arsenal has been cut rather dramatically, such that the US currently maintains a force of "only" around 3700 warheads, 1700 of which are deployed at any given time.16 This might be taken as a kind of progress, a threat environment substantively different from that of the 1980s. But to claim a substantive difference here is to replicate the absurd logic of General Buck Turgidson, the Air Force commander (played by George C. Scott) in Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, who encourages the president and the others assembled in the "war room" to appreciate the distinction between "two admittedly regrettable, but nevertheless distinguishable postwar environments: one where you've got 20 million people killed, and the other where you've got 150 million people killed!"17

![[Alt-Text: The actor George C. Scott as General Buck Turgidson, looking serious with one finger raised as he makes his point.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/barn-4-1024x621.jpg)

![[Alt-Text: Cover of Time Magazine, featuring Curtis LeMay in his Air Force hat and uniform, smoking a cigar, while B29 bombers fly overhead.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/barn-5.jpg)

General Turgidson was modeled on real-life Air Force General Curtis LeMay, who pioneered and perfected the technique of destroying entire cities through aerial bombardment, and later served as chief of staff of the Air Force under President Kennedy. LeMay was on the cover of Time the week after two of his B-29s destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a week before Agee announced the arrival of the future. But if that future would be the future of the atomic bomb, it would also be the future of the automobile. And if the world of the bomb would be marked by the infrastructures of apocalypse, the world of the automobile would be marked by petroleum infrastructure and interstate highways.

These two infrastructures converged in one of the signature achievements of the Eisenhower administration, the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956. When that bill passed, the Doomsday Clock was at two minutes to midnight, where it had been set following the Soviet Union's testing of a hydrogen bomb in 1953. In his message to congress arguing for its passage, President Eisenhower suggested that one of the advantages of better highways would be that they would "permit quick evacuation of target areas."18 This idea of escaping nuclear annihilation in the family car is almost quaint, but it also prefigures another kind of flight from American cities. If the Highways Act would do little to facilitate escape from nuclear attack, it would facilitate the more quotidian movement of white Americans into the suburbs, and "fundamentally" alter "the pattern of community development in America," which from then on would be "based on the automobile."19 And like all infrastructures, the highways had both material and ideological effects, facilitating the movement of people and things, while also promoting dreams of American freedom and prosperity. These dreams were already on offer in the advertisements peppered throughout the issue of Time in which Agee announced the arrival of the atomic age: ads for tires, for motor oil, for Chevrolets. If Agee was identifying the dawn of a dystopian future marked by nuclear terror, the ads revealed a utopian vision of a future fueled and lubricated by endless flows of petroleum. These futures would grow up together as two sides of the same coin, the latter — the good life in America — defended by the former: the threat of total annihilation of life itself.

![[Alt-Text: 1945 Advertisement shows new cars driving down a country road through a rural landscape.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/barn-6.jpg)

Though Eisenhower and Chevrolet proposed a future in which American cars and highways would enable freedom and escape, the infrastructures of automobility have ultimately left us all, as Jeffrey Insko notes elsewhere in this cluster, stuck in traffic. But even that is just one way of making the larger point that we're stuck in oil (and the climate change that comes with it). As Stephanie LeMenager has written, "We experience ourselves, as moderns and most especially as modern Americans, every day in oil, living within oil, breathing it and registering it with our senses."20 As oil fuels commuting and commerce, it also shapes our culture, from NASCAR racing and The Fast and the Furious to people's obvious investment, most anywhere in the United States, in cars and trucks and motorcycles as signs of personal and political identity. This "petroleum culture," as LeMenager calls it, has contributed substantially to a rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration of over 100 parts-per-million since the signing of the Highways Act, from around 315ppm to over 420 in 2023. The last time C02 was this high was in the Pliocene Epoch, some 3-5 million years ago — when sea levels were fifty feet higher than they are now — and it continues to rise.21 Citing this unabated rise in greenhouse gas, along with the nuclear rhetoric and policy of Donald Trump — which was even more unhinged than normal American nuclear rhetoric and policy — in 2018 the Bulletin set the Doomsday Clock once again at two minutes to midnight, right where it was when the Highways Act was passed.

From 1953 to 2018: sixty-five years of stuckness. And as of this writing, in the middle of 2023, we're still stuck — now at 90 seconds to midnight — stuck in the future as imagined in 1945, with its infrastructures of apocalypse and automobility driving us to the brink of imminent catastrophe, whether by the fast violence of nuclear destruction or the slow violence of climate change. This is, to borrow a phrase from Min Hyoung Song's brilliant new book, Climate Lyricism, pretty "fucked up." And I cite Song's explicit phrasing here because I think one thing writers and teachers and other humanists can do to confront the current global predicament is simply to speak plainly, to identify the catastrophe of the present for what it is, and thus to begin to insist on something different.22 Song addresses readers directly, inviting us — through the consideration of literature — to "feel how fucked up the everyday has become."23 This direct address is important, not only because it highlights the truly astonishing nature of the situation in which we find ourselves, but also because it rejects the isolating tendency of despair. Song asks his readers to sit together with the literature this fucked up situation has produced, to sit with "how bad this makes you feel," but not just for the sake of feeling bad. As Marx said, the point is not just to observe that the world is fucked up, but to try to un-fuck it. For Song, this begins with a simple recognition — "that my well-being, and maybe even my very survival, is bound up with yours" — that leads to a simple question: "What kinds of shared futures can you and I imagine and bring into the realm of the possible, despite a highly organized investment in business as usual?"24

It is likely that any kind of livable future will require new and improved forms of physical infrastructure, but there is a reciprocal relationship between infrastructure and imagination. On the one hand infrastructures are the products of imagination: "concrete instantiations of visions of the future," as Gupta says. On the other hand, once those infrastructures take root in material reality they shape and foreclose the range of what we can imagine. Left-leaning academics are fond of repeating what has become something of a mantra: that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. But this imaginative blockage, I think, is more often experienced in terms of infrastructure and the forms of life and patterns of consumption it enables than by the abstract idea of capitalism itself: it is easier to imagine the end of the world than a world in which I don't drive to the store whenever I feel like it; or a world in which that store is not supplied, by way of petroleum-powered just-in-time supply chains, with everything I want or could possibly imagine; or a world in which that economy is not always shadowed by the specter of nuclear annihilation. Put another way, it's easier to imagine the end of the world than a world not entirely grooved — in terms of both material life and imaginative possibilities — by the infrastructures of capital and apocalypse.

This kind of failure of imagination has contributed to failure to act on both disarmament and decarbonization. But insofar as these challenges are imaginative, I want to suggest that there is a role for literary and cultural studies in confronting them. In her book Dub: Finding Ceremony, the theorist Alexis Pauline Gumbs writes that "scholars in the humanities, and cultural workers more generally, have a responsibility for what is and is not imaginable in their lifetimes."25 If there was ever any doubt about the power of literature to open up previously unimaginable possibilities, we might recall that the atomic bomb was first imagined by the speculative fiction writer H.G. Wells in his novel The World Set Free. Writing in 1913, Wells placed the discovery of atomic energy in 1933, which would turn out to be the year in which the nuclear physicist Leo Szilard actually discovered it. Szilard had read The World Set Free the year before, and he would credit the novel with inspiring his discovery. As Richard Rhodes would later describe it in The Making of the Atomic Bomb, at that moment, on September 12, 1933, "time cracked open before [Szilard] and he saw a way to the future"; but that rupture in time was to some extent enabled by Wells's fiction.26 If we're still stuck in that future — menaced by the nuclear technology Wells made imaginable and Szilard made real — might literature offer us another crack in time, one that, unlike the Interstate highways, might actually offer a pathway to escape?

Consider Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, which is relevant here not only in a general sense — for what Kevin Powers calls its "unmatched moral clarity" for an age of mechanized violence and nuclear terror — but more specifically for its particular approach to the sensation of being stuck in that age, stuck in the time of the petroleum-nuclear complex that is killing us all.27 And that approach is simply to get unstuck in time. Billy Pilgrim, the "hero" of Vonnegut's novel, becomes unstuck in time as a result of his experience in World War Two, most notably his survival of the firebombing of Dresden. Billy becomes a time traveler, moving at random between moments of his life. At one point, Billy becomes only "slightly unstuck in time" and watches "the late movie backwards." It was a war movie about the sort of aerial bombardment he had lived through. Here's what it looked like running in reverse:

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into the cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes.28

As the planes fly backward, German fighters and anti-aircraft guns "suck . . . fragments from the crewmen and planes," repairing the damage and healing the wounded, making "everything and everybody as good as new." When the planes return (backwards) to their base, the process of reparation continues:

. . . the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling [them], separating the dangerous contents into minerals . . . The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.29

There's some fatalism in this scene — after watching it backwards, Billy watches the movie forwards again, so all the carnage plays out after all — and there's a lot of fatalism in the novel as a whole. Billy's time travels (and his space travels — he is kidnapped by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore) teach him that all events have always already happened, that there's nothing to be done about anything and therefore nothing to worry about. The Tralfamadorians even know how the universe ends — "A Tralfamadorian test pilot presses a starter button, and the whole Universe disappears."30 When Billy asks why, if they know this will happen, they don't try to prevent it, the aliens tell him that they can't, that the pilot "has always pressed" that button, "and he always will . . . The moment is structured that way."31 And ultimately the movie does replay in the normal direction, with the bombers laying waste again to the cities, suggesting that history really was just structured that way. But I think there's a reason Vonnegut lingers on this movie, sitting with it — in a novel that really flits from one thing to the next — for two whole pages. For us, sitting with Billy (as Song suggests we do) watching the movie in reverse, we apprehend not only the fucked up reality of total war, but also what Ben Lerner calls the "utopian glimmer of fiction," which opens for a moment a window onto an alternate timeline where cities are repaired and weapons of war abolished.32

While the movie scene is especially stirring in its imagination of deliberate disarmament, the novel is also bookended by explicit affirmations of this kind of agency. The penultimate chapter closes with the words engraved on the locket Montana Wildhack — another Earthling kidnapped by aliens, who becomes Billy Pilgrim's wife in captivity on Tralfamadore — wears around her neck: "God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom always to tell the difference."33 This is commonly called the serenity prayer, but it equally calls for courage and wisdom, and thus explicitly rejects fatalism, urging us not to accept but to change what we can. The prayer thus has two equally important components: acceptance of the past and the present; courage to imagine and actualize a better future.

We see both sides of the prayer at work in the other bookend, in the opening chapter, where the narrator apologizes for the mess of what we're about to read. The book, he says, which "will be my famous book about Dresden," "is so short and jumbled and jangled . . . because" it is about a massacre, and "there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre":

Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again. Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre, and it always is, except for the birds.

And what do the birds say? All there is to say about a massacre, things like "Poo-tee-weet."

"Poo-tee-weet" is the bird version of "so it goes," the book's famous recurring mantra, which the narrator repeats whenever something especially fucked-up transpires. But what the narrator says next is not fatalistic at all. Instead, it cuts through the cant of all bellicose patriotism to make a straightforward endorsement of moral agency. "I have told my sons," he says, "that they are not under any circumstances to take part in massacres . . . I have also told them not to work for companies which make massacre machinery, and to express contempt for people who think we need machinery like that."34

There is no greater massacre machinery than nuclear weapons, but the machinery of fossil-fueled capitalism — however slow its violence may seem — is not far behind. The heatwave in The Ministry for the Future — now a very imaginable event — "killed twenty million. As many people, in other words, as soldiers had died in World War One, a death toll which had taken four years of intensely purposeful killing." But this climate-induced massacre was "not genocide, not a war; simply human action and inaction, their own action and inaction, killing the most vulnerable."35 If Robinson's heatwave — which occurs in 2025 — is a thing of the past in the novel's imagined future, and thus, like the genocidal wars of the twentieth century, a thing the people of that future "cannot change," what Robinson imagines unfolding over the ensuing decades is a combination of slow, grinding policy work and technological development (urged on, it must be said, by various acts of eco-terrorism) that results in what may right now seem like an unimaginable change — an actual reduction in CO2 concentrations: "CO2 was going down at last; not just growing more slowly, or leveling off . . . but actually dropping"; and the drop was the result of human efforts: "It could only be anthropogenic. Meaning they had done it, and on purpose."36 And what Robinson's novel does for decarbonization, the movie Billy Pilgrim watches in reverse does for disarmament — which is to say it makes it imaginable.

That being said, I will nonetheless try to resist one of the other "tics" of stuck climate writing, by not concluding with an (overly) "hopeful ending." Both decarbonization and disarmament are obviously easier to imagine than to achieve, especially since (at least in the United States) we're stuck not only with 1945 ideas and infrastructures, but with a 1789 political infrastructure that actively works to undermine the will of the people, making real transformative legislation — and thus transformative infrastructures for the future — all but impossible to realize. It is perhaps a sign of the entrenchment of car culture in America that the preferred terminology for this is political "gridlock," but our stuckness with regard to planetary threats is less about car culture than it is about our deeper stuckness in the fucked-up infrastructure of American democracy. But if Vonnegut's novel reminds us that we can have a future without massacre machinery if we want one, Robinson's encourages us to keep it imaginable that the pathway to that future still might be, despite the grim prospects of the present — an age he calls the "zombie years," in which we seem to be "staggering toward some fate even worse than death" — the slow, uncertain grind of collective action. As another key text of the nuclear age — Terminator 2 — reminds us: "the future is not set; there's no fate but what we make for ourselves."37

![[Alt-Text: The gloved hand of the Terminator robot giving a thumbs up as it descends into a fiery cauldron of molten metal.]](https://wpstorage2e4b71070f.blob.core.windows.net/wpblob2e4b71070f/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/barn-7.jpg)

John Levi Barnard (@jlevibarnard) is an Associate Professor of English and Comparative & World Literature at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His recent work in literary, cultural, and environmental studies has appeared in American Literature, American Quarterly, Resilience, American Literature in Transition (Cambridge), and the Oxford Handbook of Twentieth-Century American Literature.

References

- Mohini Chandola, "Climate Scientists Compare India's Rising Heatwave to a Popular Sci-Fi Book," The Quint, April 26, 2022. On the heat waves more generally, see Benji Jones, "This Could Be the Coolest Summer of the Rest of Your Life," Vox, June 22, 2022.[⤒]

- Michael Francis Gore and Silvio Castellanos, "Spain's Heatwave Taking a Toll on Young Birds," Reuters, June 15, 2022; Amy Cheng, "Extreme Heat and Humidity Kill Thousands of Cattle in Kansas," Washington Post, June 16, 2022; Eric Schlosser, "What if Russia Uses Nuclear Weapons in Ukraine?," The Atlantic, June 20, 2022. [⤒]

- "A Time of Unprecedented Danger: It Is 90 Seconds to Midnight," Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, January 24, 2023.[⤒]

- Michael Bierut, "Designing the Doomsday Clock," The Atlantic, 5 November 2015.[⤒]

- On these nuclear false alarms, see the Union of Concerned Scientists "Fact Sheet" on "Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons."[⤒]

- This meme is everywhere, but the original comic is here: https://gunshowcomic.com/648. [⤒]

- Reagan Pearce, "Are You Suffering from Shifting Baseline Syndrome?", Earth.org, 19 June 2020.[⤒]

- Heather Houser, "Is Climate Writing Stuck?", LitHub, 3 January 2022.[⤒]

- For just such a graph, click here.[⤒]

- Svante Arrhenius, "On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground," The London, Edinburg, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 5.41 (April 1896): 237-276; on Hansen's testimony, see Elizabeth Kolbert, "Listening to James Hansen on Climate Change, Thirty Years Ago and Now," New Yorker, 20 June 2018. [⤒]

- Thorfinn Stainforth and Bartosz Brzezinski, "More than Half of All CO2 Emissions since 1751 Emitted in the Last 30 Years," Institute for European Environmental Policy, 29 April 2020. [⤒]

- Elizabeth Kolbert, Field Notes from a Catastrophe (New York: Bloomsbury, 2006), 189.[⤒]

- Akhil Gupta, "The Future in Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure," in Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, eds., The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham: Duke UP, 2018), 63.[⤒]

- James Agee, "The Bomb," Time Magazine, 20 August 1945. [⤒]

- Jessica Hurley, Infrastructures of Apocalypse: American Literature and the Nuclear Complex (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020); Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, "Global Nuclear Weapons Inventories, 1945-2010," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 66.4 (2015): 77-83.[⤒]

- Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, "Nuclear Notebook: How Many Nuclear Weapons Does the United States Have in 2022?", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 10 May 2022. [⤒]

- Watch it here![⤒]

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, "Message to Congress," 22 February 1955, Eisenhower Library.[⤒]

- "National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (1956)," National Archives.[⤒]

- Stephanie LeMenager, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 6.[⤒]

- "CO2 Concentrations Hit Highest Levels in 3 Million Years," E360 Digest, 14 May 2019. [⤒]

- I can't help noting that I am currently, in central Illinois, breathing officially "unhealthy" levels of smoke from wildfires in Canada. This is now normal and it is totally fucked up.[⤒]

- Min Hyoung Song, Climate Lyricism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), 14.[⤒]

- Song, 15.[⤒]

- Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Dub: Finding Ceremony (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), x. I am indebted to Erin Grogan for drawing my attention to this passage.[⤒]

- Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), 13, 24. See also, Hannu Rajaniemi, "Time Cracks Open for Leó Szilárd in Richard Rhodes's The Making of the Atomic Bomb," Tor, 26 June 2018. [⤒]

- Kevin Powers, "The Moral Clarity of 'Slaughterhouse-Five' at 50," The New York Times, 6 March 2019.[⤒]

- Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969; Rpt. New York: Dell, 1991), 74.[⤒]

- Vonnegut, 74-5.[⤒]

- Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, 117.[⤒]

- Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, 117.[⤒]

- Ben Lerner, 10:04 (New York: Picador, 2014), 54.[⤒]

- Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, 209.[⤒]

- Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, 19.[⤒]

- Kim Stanley Robinson, The Ministry for the Future (New York: Orbit, 2020), 227.[⤒]

- Robinson, The Ministry, 445.[⤒]

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iSmxFLqCps.[⤒]