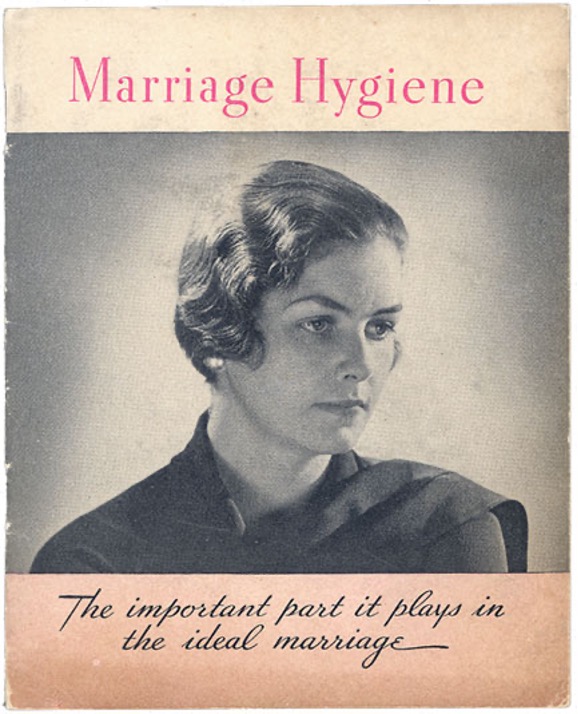

Keywords for Postcolonial Thought

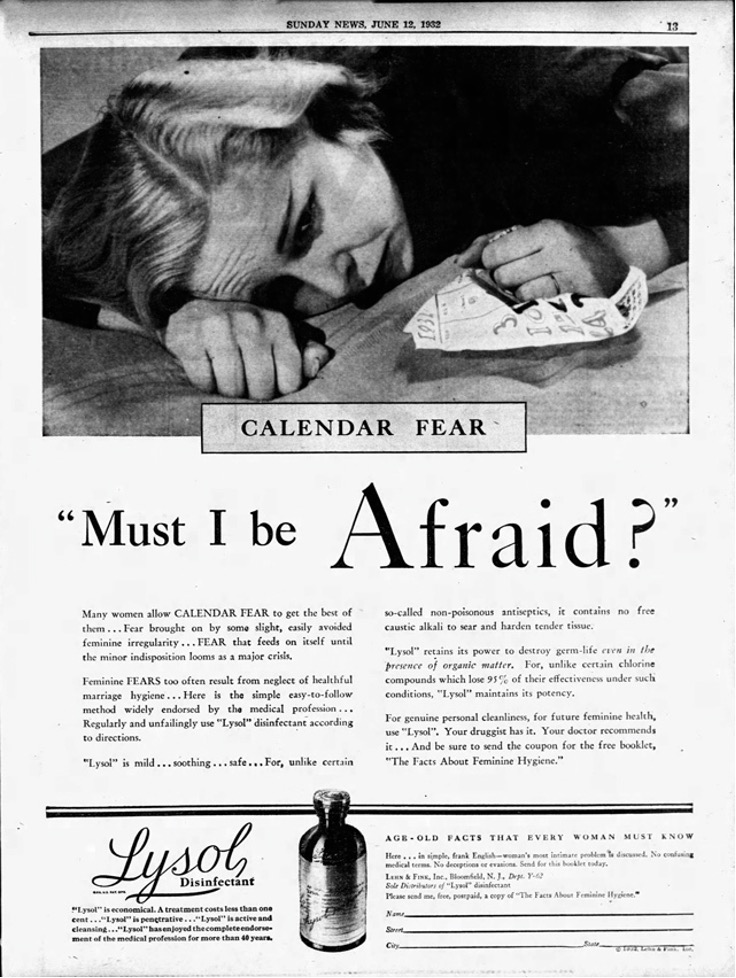

"Marriage hygiene" may not be a keyword now, but it was in the 1930s, when it was used chiefly as a euphemism for birth control. It appeared prominently in Lysol ads, for example, to help promote it as a vaginal cleanser and, tacitly, as a means of preventing pregnancy. Despite being rife with harmful misinformation, Lysol's ad campaign was extraordinarily successful — Lysol in douche form became the best-selling female contraceptive in the country by the late 1930s, and remained the leading feminine hygiene product until the 1960s.1 Part of the reason the disinfectant brand was able to get away with its outrageous advertising claims was the 1873 Comstock Act — a vice law which made it illegal to circulate information about birth control, as well as other materials deemed "obscene" — leaving women ill-informed about their options and susceptible to the vague promises of ads like the Lysol ones.

Figure 2, Ad for Lysol, 1932

During the same decade, the phrase was used in a different euphemistic mode in India, where it was the title of a sexology journal published out of Bombay (its editors having deemed the word "sexology" too controversial). Marriage Hygiene is all but forgotten today, but it played a central role in shaping a global conversation about eugenics that involved virtually every influential thinker on the topic.First drawn to the journal by its perplexing name and then riveted by its alternately enlightened and repugnant content, I came to see it as emblematic of a key moment in the history of eugenics in India and beyond: one that sheds light on the transition from empire to postcolony, from British to American influence in South Asia, and from hard to soft forms of imperial power, such as the marketing of birth control to Indian women and the promotion of population control at the state level. While Marriage Hygiene opened up an avenue for American influence in India, it affected the US in turn, when its circulation here led to a legal challenge to censorship law. This history, close to a century old, has become newly relevant in the US as eugenics and birth control medicines have resurfaced as vectors in the fight against reproductive rights. "Marriage hygiene" is no longer used as a euphemism but the things it named — eugenics, birth control, and their interrelation — are still the site of a struggle for control over women's bodies. A closer look at the journal allows us to see how eugenics discourse and birth control first circulated together and how the instrumentalization of women of color has been one of the most persistent and pernicious features of their interconnection.

Marriage Hygiene was published from 1934 to 1937 and then again from 1947 to 1955. Its compound title accentuated its eugenicist aims, with hygiene signifying a rational approach to sex, and marriage suggesting the way sex should be contained; as many articles in the journal argued, the institution was vital to raising healthy and happy children. If by decoupling sex from reproduction and investigating its histories, meanings, and possibilities, sexology destabilized traditional thinking about sex and marriage in ways that were potentially threatening to the normative family unit, eugenics was the solution — the means by which sex and reproduction were sutured back together. Marriage needed good sex in order to last and thrive, eugenicists argued, while sex needed to be channeled into marriage so that reproduction might be contained and made intentional.

The journal's founder and editor was an Indian doctor, A.J. Pillay, who played a leading role in a number of local eugenics initiatives, but who also forged ties with eugenicists abroad. He connected with American birth control advocate Margaret Sanger and made her Vice President of his Family Hygiene Society, and worked tirelessly to win his journal a global audience. Because he offered contributors an international platform at a time when both sexology and eugenics were controversial subjects in their own countries, he was able to secure articles from high-profile Western thinkers such as Havelock Ellis and American sociologist Norman Himes, who then championed Marriage Hygiene among audiences in Britain and the US.

Despite its prominent international contributors, Marriage Hygiene eventually ran into trouble in the US when customs authorities clamped down on its circulation because its articles and advertising about birth control violated the Comstock Act. In 1937, however, with the support of ACLU lawyer Morris Ernst, the journal took the government to court for censorship and won. In a case entitled United States vs. Certain Magazines, the court decided that contraceptive literature could enter the U.S. without customs interference, so long as the consignee was a person "qualified" to receive it. Himes, who played a central role in the lawsuit as the qualified person in question, wrote a victorious letter to the Editor of the Eugenics Review stating that "the Comstock Act has been notably amended, if not all but wiped out."2

As we now know, however, the Comstock Act was not wiped out; instead, it has been dusted off and is now a centerpiece in the right wing attack on abortion. Because the Act prohibited not only the circulation of birth control information but of birth control itself, conservative judges have argued that it could be used to block the mailing of abortion medication. Another crucial element related to the history of Marriage Hygiene has been enlisted in the right's attack on abortion as well: in 2019 Clarence Thomas wrote an opinion in favor of a Supreme Court ruling on Indiana abortion law in which he argued that birth control and abortion are suspect because they were once used in the service of eugenics. Calling out the eugenical beliefs of Margaret Sanger in particular, so as to discredit Planned Parenthood (with which she is enduringly associated), Thomas argued that abortion can be used to prevent certain citizens who have been deemed less desirable — such as people of color and those with disabilities — from reproducing or being born in the first place.

As many historians immediately pointed out, Thomas' opinion was deeply flawed.3 For one thing, abortion was never a major tool in the arsenal of eugenicists and, as he himself acknowledges in the opinion, Sanger sought to publicize birth control partly to obviate the need for abortion. For another, the chief problem with eugenics is that it redistributes reproductive agency from the individual to the state, thereby threatening bodily autonomy, which is precisely what Dobbs has done. Because abortion affects Black populations disproportionately, Thomas argued that making it widely accessible is a threat to the future of the Black community. What he didn't say is that when it is outlawed, Black women are forced to do the work of reproducing the race even when they would elect not to: a violation of their autonomy that recalls the dehumanizing conditions of slavery that Thomas uses to justify his anti-abortion stance.

But Thomas was not wrong about the way the circulation of birth control information and ideas about eugenics were linked in Sanger's time. As Dorothy Roberts has argued in relation to the American context, "Birth control became a means of controlling a population rather than a means of increasing women's reproductive autonomy . . . [it] was defined from the movement's inception in terms of race."4 As Marriage Hygiene demonstrates, the racialized treatment of populations played out on the global scale as well, and partly because of Western eugenicists like Sanger. Marriage Hygiene's editorial advisory board initially consisted entirely of Indian male medical practitioners, and early issues featured Indian issues prominently. But from its first issue, Marriage Hygiene also showcased key Western figures (along with Ellis and Sanger, these included Marie Stopes, Julian Huxley, and C.P. Blacker, prominent members of the British Eugenics Society). The relationship between the influential British and American eugenicists who wrote for Marriage Hygiene and its Indian editor was mutually beneficial but to opposing ends. Anglo-American writers gained wider circulation for their controversial work through the journal and, perhaps more importantly given the racist political aims of their advocacy, an inroad into India which, along with China, increasingly epitomized to many Western eugenicists the problem of overpopulation, particularly in the wake of large waves of Asian immigration to the West in post-war period. Significantly, it was Norman Himes's idea and not Pillay's to "expand the journal into an international publication with a Board of Editors [that included] representatives from the major countries" even as Pillay initially expresses skepticism about the "difficulty of working this up from a city like Bombay."5 Meanwhile, European pharmaceutical companies gained inroads for their birth control products to a potentially enormous market via the journal's ads, at a time when countries like the US were still outlawing the circulation of such information.

From the Indian perspective, the eugenics conversation was part of the global Anglosphere that Indian writers might enter as equals, leap-frogging from the waiting room of not-yet-ready-for-modern-nationhood to the vanguard of scientific discourse. As I have argued elsewhere, colonial censorship law, by criminalizing "disaffection," racialized the public sphere by associating Indian critical thought with excessive, destructive, and atavistic affect.6 With its goal of dispassionately observing affection and channeling it to the ends of human progress through international scientific cooperation, Marriage Hygiene emblematized the opposite, and thus offered an escape from the bind of second-class citizenship in the public sphere that censorship had created. While non-Western countries were positioned as belated in their engagement with modernity, the distinctive temporality of eugenics, in its focus on the future perfectibility of national populations, implied a shared imperfect present: all people engaged in its project were poised together at the threshold of history, collaborating to bend it to their will. Eugenicists would have to collaborate internationally to realize their vision, not only because of the need to sway global public opinion in their favor but because of their desire to contain population within borders, as well as numerically.

While the eugenics conversation seemed to pave the way to an equalizing internationalism for its Indian contributors, it also helped to shape and stoke Indian nationalism. An important context for eugenics in India, as critics such as Mrinalini Sinha, Asha Nadkarni, and Rovel Sequeira have argued, was Katherine Mayo's 1927 book Mother India, a virulently racist ethnography associating India with sexual depravity and disease that she had been encouraged to write by the British government to shore up support for empire.7 In the huge international controversy that followed its publication, Indian nationalists turned the narrative around, blaming the colonial government for failing to reform hygiene, sex, and reproduction. In this context, eugenical sexology became one of the grounds from which to assert both India's modernity and its distinction from the West.8 A 1934 essay in Marriage Hygiene titled "The Indian Outlook on Sex Relations," for example, implicitly counters Mayo's indictment of Hinduism as the source of India's backwardness by arguing that ancient Hindu philosophy celebrates "the enjoyment of the pleasures of the flesh for the full and complete development of all [human] functions . . . "[L]ong before the advent of the Christian era, our ancestors could recognize the fact that the exercise of the normal sex impulses was a paramount necessity and imperative for the preservation of health."9 Arguments such as these made the "science of sex . . . both authentically Hindu/Vedic in a way that served the new science in its global career (by giving it a claim to antiquity), and aided high-caste Hindu claims on the national platform (by justifying its gender, caste and communal hierarchies as timeless, authentic, and premised on a secular science)."10 Debates about sterilization and birth control in the journal also reinforced caste hierarchies. B.N. Adarkar, writing on "The Problem of Sterilisation in India" to promote its legalization, argued that it was "of special importance for women belonging to the lower classes," thus paving the way for the sterilization policies directed at lower caste populations later in the century.11

Yet despite its focus on their bodies and the fact they were agitating for reproductive rights in forums such as the All-India Women's Conference (whose first meeting in 1927 pre-dated Marriage Hygiene), women's voices were missing from the journal.12 Nadkarni's Eugenic Feminism demonstrates that a number of Indian feminists advocated for the importance of women's reproductive agency, and thus female agency more broadly, to the success of a future India.13 This agency was notably caste-bound; after independence, eugenic feminists such as Rama Rao joined Western ones like Sanger in focusing on the regulation of reproduction in lower-caste populations.14 Yet even this compromised feminism was missing from the journal. If marriage, as Gayle Rubin famously argued, was historically structured as a homosocial exchange between men, Marriage Hygiene enacted this exchange with women's bodies as discursive rather than material currency.15

The journal even set itself up as a form of male bonding — or made male bonding part of its form — by recurrently stating in its front matter that it sought "to bind its readers together in a brotherhood of clean thinkers and bold fighters against prejudice, evasion, and meaningless taboos."16 But to forge their brotherhood of "clean thinkers and bold fighters" and create an international conversation in which they functioned as equals, the editors of Marriage Hygiene erased the actually-existing agency of Indian women and made them the particular concern of Indian men and of Western women, such as Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger, whose work in the journal focused on birth control in India. If all women had currency in the journal as objects of eugenical concern in their respective nations, Indian women, longtime targets of imperial scrutiny, were particularly valuable. Their silence in their journal helped to valorize Western intervention in the form of white women saving brown women from brown men, or at least from the perils of brown sex, which many of the journal's articles associated with excessive reproduction and corollary health issues. Thus even as Indian sexologists sought to counter Western views of India circulated by imperialists like Mayo, they played into them by erasing the work of Indian feminists.

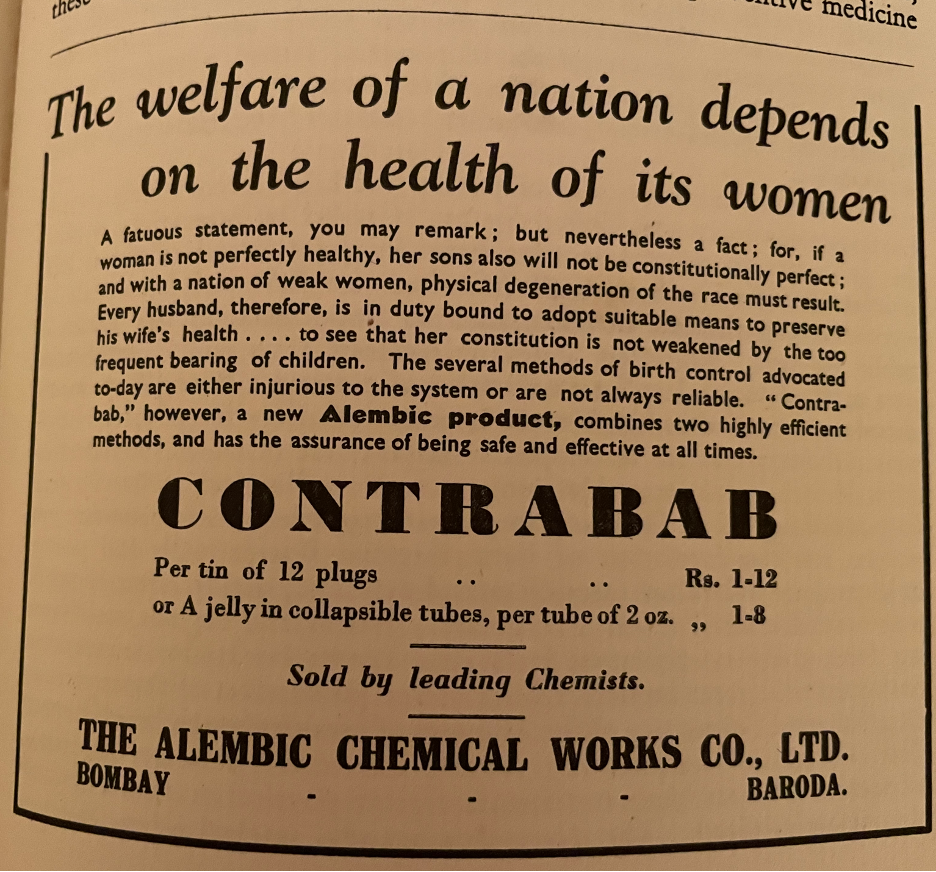

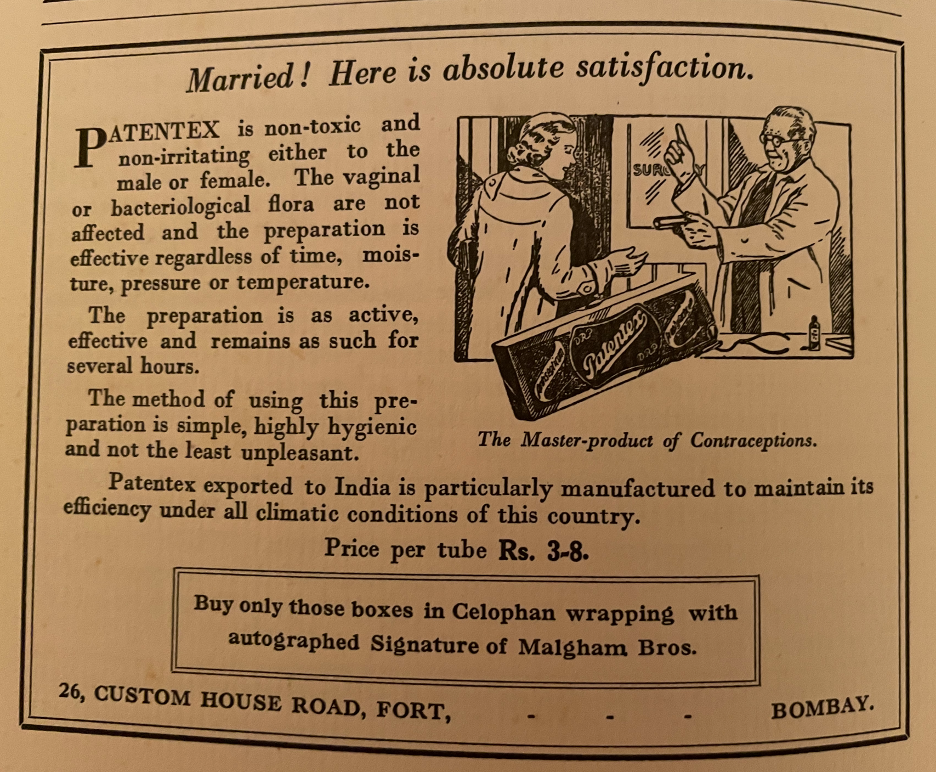

To the extent that Indian women's agency was visible in the journal, it was as consumers, for Marriage Hygiene's copious ads for contraceptives and various elixirs promising "healthy womanhood" were aimed at them. But this agency, too, was circumscribed: an ad with the headline "The welfare of a nation depends on the health of its women," for example, stated that "every husband is duty bound to adopt suitable means to preserve his wife's health . . . to see that her constitution isn't weakened by the too-frequent bearing of children."17 All ads, meanwhile, targeted an English-speaking upper-caste readership. In one of the early issues of the journal, Marie Stopes, after describing in excruciating detail the way "the poor women of India" might use cotton waste and oil as a DIY contraceptive sponge, hoped weakly that this information would somehow be communicated to them, while noting, in a nod to the journal's ads, that "For the well-to-do Indian women, educated, and with sufficient money to spend on hygienic requirements, some scientific and precise method may be better suited."18 While Indian women were implicitly divided by the journal into rich and poor, they were all spoken for by others.

In this way Marriage Hygiene presented a distorted view not only of India but of Indian sexology. As Charu Gupta has shown, women and Shudra writers like Yashoda Devi and Santram B.A. were prolific and popular authors of sexology texts that challenged the caste and gender hierarchies shored up by Marriage Hygiene even as their writing was sidelined in mainstream sexology discourse.19 As the journal became increasingly successful and international in scope, male Indian voices were sidelined as well. By the time the journal morphed into the International Journal of Sexology in 1948, Indian articles appeared much more infrequently. Whether Pillay deliberately yielded space he could have held for India in the journal in favor of international expansion or was edged out by his non-Indian collaborators, the ceding of ground reflected the way debates about birth control in India, internationalized by Marriage Hygiene, had paved the way for US intervention in the form of development aid contingent on population control.20

If an emphasis on individual birth control and positive eugenics had morphed into population control and negative eugenics by the 1950s, eugenicists had retreated back to sexology. At the beginning of Marriage Hygiene's run, it was sexology that dare not speak its name; in the wake of the Holocaust, "hygiene," now ineluctably redolent of Nazism, was even more undesirable: the journal's change of title to the International Journal of Sexology in 1948 reflected this discursive shift. In its last run (1947-1955), then, the journal devoted as much space to the mysteries of the female orgasm as it once had to sterilization and birth control, demonstrating that the problem of women's bodies, ever the enigmatic, generative subject at the heart of sexology, continued to serve as the journal's international currency of scholarly exchange.

This snapshot of eugenics through the lens of a now-obscure Indian journal shows how the relation between empire and intimacy pivoted over time. After the period of Marriage Hygiene, debates over birth control in India shifted to national policies of population control motivated by international aid and agencies and the attempts to control and contain sex morphed from the cultural and relational to the medical: the discipling of the body from the outside in, from pills and gels to tubal ligation and vasectomies. The aggressive sterilization programs of post-independence India, which continued even after the notorious forced sterilizations of the Emergency, targeted "the illiterate, economically disadvantaged, Dalits . . . members of other disadvantaged castes, and Muslims."21 As we have seen, the discourse of eugenical sexology in Marriage Hygiene aligned with feminism, but far from perfectly. Birth control promised women more autonomy in theory but in the context of eugenics could be used oppressively, and all too often was. One legacy of the Marriage Hygiene era is that sterilization is the most frequently-used method of birth control in both India and the US.22 This wouldn't be disturbing if the practice was always initiated by women themselves, but in both countries there have been rampant cases of sterilization abuse from the heyday of eugenics up until the present, and the victims are almost always minoritized women.23

If eugenics and contraception intersected in the 1930s in ways that obscured and circumscribed the agency of women in India, they have re-emerged in the contemporary US in an entirely different and confounding way — instead of being used to promote birth control, eugenics is being used as an argument against it. But once again women of color, spoken for by Clarence Thomas, are being conscripted into nationalist narratives about the future of the race that, like the Lysol ads, conveniently leave out key details in order to bypass informed consent and sell dangerous intrusions on women's health as liberation.

Tanya Agathocleous is Professor of English at Hunter College, CUNY. She is the author of Disaffected: Emotion, Sedition and Colonial Law in the Anglosphere (Cornell University Press, 2021) and Urban Realism and the Cosmopolitan Imagination (Cambridge University Press, 2011). She is currently working on two books, one that uses the concept of marriage hygiene to explore sex and soft power and a project on race, caste, and empire co-written with Janet Neary.

References

- Andrea Tone, Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 160.[⤒]

- Norman Himes, "Birth Control Laws in the U.S.," Eugenics Review 30, no. 3 (Oct. 1938), 227.[⤒]

- Eli Rosenberg, "Clarence Thomas Tried to Link Abortion to Eugenics. Seven Historians Told the Post He's Wrong," Washington Post (May 30, 2019), np., https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/05/31/clarence-thomas-tried-link-abortion-eugenics-seven-historians-told-post-hes-wrong/.[⤒]

- Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (Vintage, 2014), 80.[⤒]

- Editor, "Editorial Notes," Marriage Hygiene 1, no. 1 (August 1934), 2.[⤒]

- See Tanya Agathocleous, Disaffection: Emotion, Sedition, and Colonial Law in the Anglosphere (Cornell University Press, 2021).[⤒]

- See Asha Nadkarni, Eugenic Feminism: Reproductive Nationalism in the United States and India (University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Rovel Sequeira, "The Sciences of Love: Intimate 'Democracy' and the Eugenic Development of the Marathi Couple in Colonial India," History of the Human Sciences 36, no. 5 (2023): 68-93; and Mrinalini Sinha, Specters of Mother India: The Global Restructuring of an Empire (Duke University Press, 2006).[⤒]

- On this subject, see Sequeira on the effect of the 1929 Child Marriage Restraint Act and the way sexologist and novelist Narayan Phadke "domesticated eugenic sexology for its 'vernacular' audiences by advocating caste-bound romantic love as the blueprint for Indian marital coupling" (68).[⤒]

- Romeschandra Rakshit, "Indian Outlook on Sex Relations," Marriage Hygiene 1, no. 2 (November 1934): 146-52, 147.[⤒]

- Pande, "Introduction,'" South Asia 43, no. 6 (2020), 1099.[⤒]

- B.N. Adarkar, "The Problem of Sterilisation in India," Marriage Hygiene 1, no. 2 (November 1934): 180-4, 183.[⤒]

- Barbara N. Ramusack, "Embattled Advocates: The Debate Over Birth Control in India, 1920-40" Journal of Women's History 1:2 (1989), 34-64, 41.[⤒]

- Nadkarni, Eugenic Feminism.[⤒]

- Nadkarni, 3-4.[⤒]

- Gayle S. Rubin, "The Traffic in Women: Notes on the "Political Economy" of Sex" in Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (Duke UP 2020), 33-66.[⤒]

- Marriage Hygiene, inside front cover.[⤒]

- Ad in Marriage Hygiene 1, no. 2 (November 1934), 179.[⤒]

- Marie Stopes, "Contraception for Indian Women" Marriage Hygiene Nov 1.2 (1934):143-5, 144.[⤒]

- Charu Gupta, "Vernacular Sexology from the Margins: A Woman and a Shudra," South Asia 43, no. 6 (2022): 1105-1127.[⤒]

- For more on the U.S. involvement in Indian population control efforts, see Nadkarni, Eugenic Feminism and Birth Controlled: Selective Reproduction and Neoliberal Eugenics in South Africa and India ed. Amrita Pande (Manchester UP, 2022).[⤒]

- Amrita Pande, "Birth Projects, Selective Reproduction and Neoliberal Eugenics," in Birth Controlled: Selective Reproduction and Neoliberal Eugenics in South Africa and India ed. Amrita Pande (Manchester UP, 2022), 17.[⤒]

- On the Indian context, see Anjali Bansal, Laksmi Kant Dwivedi, Balhasan Ali, "The Trends of Female Sterilization in India: An Age Period Cohort Analysis Approach" BMC Women's Health 5, no. 22 (July 2022), 272. For the US, see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db327.htm.[⤒]

- On sterilization abuse in the US, see Roberts, 89-98. Newer cases than those covered in her book include the sterilization of immigrant women in ICE detention centers as recently as 2020.[⤒]