Asian/American (Anti-)Bodies

Devouring Coolie Bodies: On Raj Kamal Jha’s She Will Build Him a City

" . . . the fleshing of a particular (textualized and centric) Babu worldview [is] a legitimate enough activity in itself, but for the fact that such fleshing is often a cannibalistic act, shall we say, of devouring Coolie bodies, of stripping non-Babu worlds to (at the most) a bare skeleton."

— Tabish Khair, Babu Fictions1

"He watches the birds begin to peel her skin, tear her earlobes away . . . He wants to put his mouth there, where she bleeds, drink it all in, feel the wind from the flutter of the birds' wings in his face."

— Raj Kamal Jha, She Will Build Him a City2

First, the disclaimer: Raj Kamal Jha's She Will Build Him a City (2015) is not in conventional terms an Asian American novel, nor is the India-based Jha an Asian American writer—at least not according to a "minimal definition" of such authorial identity.3 But in what follows, I want to suggest that She Will Build Him a City's graphic rendering of the "Coolie body" and its cannibalization offers a response to Tabish Khair's well-known critique of Indian Anglophone expatriate (including Indian American) writing as "Babu fiction," as well as to Rachel Lee's provocation that anxieties about biological assignment and "embeddedness to race" in Asian Americanist critique might equally reflect anxieties about "the shifting (posthuman) meanings of being biological."4

She Will Build Him a City, Jha's fourth novel, is set in Delhi and the "New City" that sits twelve stops away from Rajiv Chowk Station on the Delhi Metro. The renomination as "New City" of what readers might reasonably assume is meant to be Gurgaon—India's paradigmatic "nonplace," a "city of glass ... defined by its future"5—is an obvious gesture toward the global form of the nation known in popular parlance as "New India." It is also part of Jha's larger strategy of selectively evacuating many of the novel's people and places of characterological specificity, while allowing certain of their identifying traits to assume protonymic proportions. The novel unfolds as a series of short, rapidly-shifting chapters alternately focused on the stories of "Woman," "Man," and "Child," interrupted with brief "Meanwhiles" centering on other minor characters, whose stories contribute to the novel's panoramic portrait of metropolitan Indian life. "Balloon Girl"—she of the epigraph's bloody bird repast—is one such character, who assumes greater centrality as the novel unfolds.

We've seen this minimal and playful form of denotation used to address an allegory of Indian subcontinental globality before, most recently in Mohsin Hamid's How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (2013), in which "Asia" is the novel's only proper-named character or place. But whereas Hamid's aspiration is the elevation of entrepreneurial placelessness to universal relevance, Jha is aiming for something different: a placelessness and facelessness particular to New India and of a fragmented, specifically Indian body politic struggling to constitute itself as a society of shared interests. While the evocations of "Woman," "Man," and "Child" initially suggest the disassembled component parts of a nuclear family, which the narrative promises to recompose, the novel ultimately flouts the desire for familial wholeness, in ways that make salient each individual's thoroughgoing isolation in New India's New City.

Woman is a mother who has lost her husband (in a bus collision) and very nearly her daughter, too, a returned-runaway who spends much of the novel as a sleeping non-presence, and whose awakening the Woman eagerly awaits. Man, a wealthy, educated resident of Apartment Complex in New City, is given to lurid fantasies of violence, sex, and death. His is an aestheticized erotics of murder: "No knife, no thick rope, no iron rods" (5). He imagines his fellow Metro-riders "slit open" and is aroused in anticipation, just as long as there is no unsavory "wet ... spray or splatter" (5). Finally, Child is an orphaned infant abandoned on the steps of Little House and cared for there by a nurse, Kalyani Das, until a stray dog, Bhow, whisks him away to The Mall. There, amidst 208 stores featuring "one kilometre of shopping experience" (168), Orphan makes his home in the Europa theatre. He is looked after by the "cinema woman," Ms. Violets Rose (an anagram for Love Stories), who transports the child into the filmic worlds shown on screen (205).

She Will Build Him a City is a parable of the New India that flits between the stories of motley citizens, from news anchor, to child-laborer, to mysterious cinema sprite. But its most provocative depictions center on encounters between elite Indians and putative subalterns (Babus and Coolies, in Khair's terms), like Man and Balloon Girl, respectively. In an early scene, Man (probably?) rapes and murders Balloon Girl. That parenthetical question is the reader's, but it is also Man's; after their initial meeting, he cannot recall if he has indeed committed the crimes he later hears about on television. As he watches the grisly report, a self-doubting monologue merges with the news ticker, flying off the TV screen, into the air, and onto his skin:

CHILD RAPED, KILLED, MOTHER SEVERELY ASSAULTED . . . IF HE DOES RAPE HER, IF HE DOES KILL HER, HOW DOES HE RAPE HER? . . . HE DOES NOT USE A GUN BECAUSE HE DOES NOT HAVE ONE DOES HE STRANGLE HER? . . . SHE WILL BITE, SHE WILL SCRATCH, BUT THEN WHERE ARE THE MARKS, THE CUTS AND THE BRUISES? (186-188)

Aware that he desired—and desires still—to ingest her ("He wants to swallow her lips" [98]), but unsure if he has killed her, Man is haunted by visions of Balloon Girl, who, as the novel progresses, leads him through New City, India, and abroad while goading him into at least one other murder. Man's fantasies are ugly, pornographic (there is a scene of necrophilic lust at a morgue), but his savage impulses are, the novel provocatively suggests, really just the other side of the charitable coin. On the one hand, Man "wishes to hurt [Balloon Girl], drink her blood"; on the other hand, he desires "to take her off this city's streets ... share with her his own good fortune ... [his father] would be proud if he took in a child from the street, cleaned her up, gave her his love, made her his own" (324).

The humanitarian intervention (taking the child "off this city's streets") is belied by the possessive urge that precedes it, revealing the extent to which the philanthropic mission can—perhaps even often does—mask an underlying misanthropy. To borrow Fredric Jameson's estimation of George Gissing's attitude toward "the people," Man evinces a "combination of revulsion and fascination" toward subalterns like Balloon Girl.6 But rather than neutralize this affective disposition in a familiar slumming narrative, Jha develops it to the extreme, so that middle-class class anxieties cannot, finally, be "resolve[d], manage[d], or repress[ed]."7 Rather, in a form of reverse sublimation, such anxieties eschew taking sanctified moral form in favor of expression as cannibalistic desire: to consume the Other; to be one with Other; to make the Other disappear.

The consummation of such desire is, in the final instance, self-annihilating. Eventually, spectral visions of Balloon Girl, dancing and beckoning to him from over the ledge outside his apartment window, lead to Man's guilt-ridden suicide.

*

There is more than a little posthuman "magic" in this novel that simultaneously confounds linear plot-ordering, spatio-temporal location, everyday logics of animal behavior, and the laws of gravity. But She Will Build Him a City is less a return to that old magical realism of Salman Rushdie (to whom Jha nevertheless gives a nod via an epigraph from Oliver Twist: "Midnight had come upon the crowded city...") than a commentary on what Ulka Anjaria terms the "new social realisms" of contemporary Indian Anglophone novelists like Aravind Adiga, Chetan Bhagat, and Manu Joseph, among others.8

In a recent essay, Anjaria proposes that the contemporary Indian Anglophone novel is marked by a simultaneous return to realism and a reformist impulse to lay bare the structural inequalities in global India. This new social realism "maintains a commitment to representing social injustices through a materialist lens" while eschewing, or transcending, the familiar "politics of visibility."9 For Anjaria, the illegibility and fictionality of the "real" world of New India depicted—for example, in Adiga's already-classic The White Tiger (2008)—points to the "fundamental irreconcilability between the middle-class tourist gaze and the social inequality it seeks to represent."10 This realism is a "perplexing," not revealing, mode of literary capture, a mode "invested more in sounding out the dialectic between communication and obscurity than in conveying a transparent truth."11

She Will Build Him a City offers a similar "aesthetics of indeterminacy"12—Did Man rape and murder Balloon Girl? Is there in fact an Orphan living in The Mall?—while committing originally to a politics of corporeality that, depending on your reading, either reduces or elevates each subject to the determinate wonders and horrors of the physical body. "There are 20 million bodies in this city," the novel establishes in its first pages, "and then there is the heat" (6). What follows does not simply "[render] present" these 20 million, nor narrate "their gradual incorporation into an aspirationally expanded public sphere."13 Rather, the novel's macabre aesthetic renders presence itself a form of acute vulnerability to others and risk to oneself. Man, fastidious and compulsive, is the most sensitive to the presence of the bodies of others, especially his Drivers: "Human, male, unwashed after fourteen hours in the sun...shirt soaking rivulets of sweat ... The collar that smells of last night's drool ... Like Dog smell on that Diwali evening ... Maybe drops of urine spattered in the underwear ... sweat near the anus" (266-267). Before he takes Taxi Driver's life, before he put Balloon Girl and her Mother to sleep, Man forces them to bathe at length, with so much water and soap that, as Taxi Driver says, "I am cleaner than clean, this is like when I was born" (268).

If Man's preoccupation with the body were unique it might simply be a sociopathic aberration. Instead, the novel itself consistently figures its subjects as bodies first—elemental, primal, literal—and only then potential speakers and actors in a broader social sphere. Throughout the text, what draws or repels one individual to/from another is his or her blood, sweat, skeleton, from Woman's "first touch" of her infant daughter's "damp and soft" skin, to the straining "thin shoulders" of Baba, the cycle rickshaw-wallah, "the veins in his calves distended under the skin, sweat dripping down his back" (289).

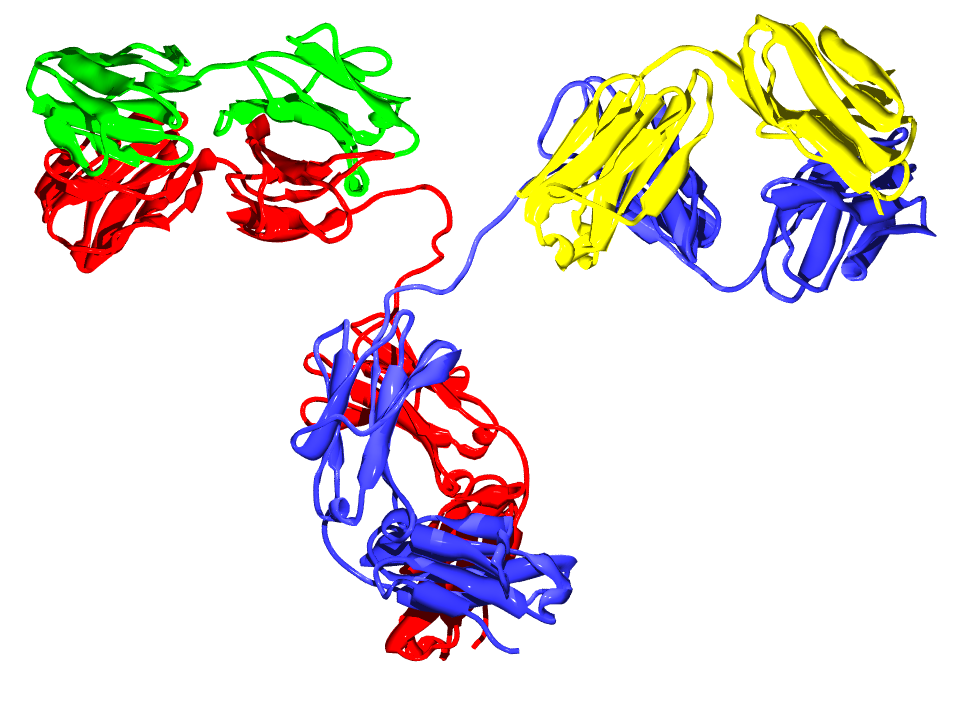

In one of the many "Meanwhile" chapters, a medical student daydreams about a fellow classmate's body—all of it:

He loves her capillaries, blood flowing, red blood cells, layers of tissue, blue, red, white, dermis, bones, heart ... the pineal gland that regulates her waking and her sleeping, her uterus where he hopes one day there will be someone, his or her little heart beating because of their love, even her large intestines holding her waste, honey brown, her kidneys that keep her clean. (290)

This is Jha's somatic spin on the return to realism. The social critique follows just two pages later, as the medical student, now called Quota Boy, finds out that the embodied subject he desires is protesting the policy of Reservation (a form of quota-based affirmative action) in the medical college. Quota Boy is the son of "backward-caste" parents (292), so, in effect, she is protesting him, his admission, the presence of his body. No heart will beat in her because of their love.

The body, then, is possibility, but it is also treachery—at once the primary organ of sensation, the locus of meaning, the enabling condition of social advancement, and the repository of social and biological disease. This multiplicity of meaning is most evident in the figure of Kalyani Das, a nursing student with ambitions of moving to America. The daughter of Baba the rickshaw-wallah, she lives with her parents and siblings in one room in a Delhi slum. "[N]urses will always be in demand," she tells her superior, Dr. Chatterjee, "[because w]ho is going to clean you up when you wet your bed? ... I am learning not to smell the smells ... it doesn't matter if I do this here or in America because shit, piss, blood, they all look and smell the same wherever you are, whoever you are" (21-22).

Kalyani's confident pronouncement comes early in the novel, and for good reason: This idea that bodies are all the same—that despite differences of geography, culture, location, and color, shit, piss, and blood all look and smell the same—will be tested, and found wanting, many times. For despite the commonsensicality of this seeming sameness, not all bodies are created equal. Not all bodies move and migrate with equivalent freedoms. Bodies carry the colors of caste, the sweat of sun exposure, the skeletons of labor, the blood of disease. To have an Asian American body—Kalyani's dream—one must bear a body that registers the discursive labor of Asian racialization, but it must also, and first, satisfy the minimal requirements of life and its reproduction. Despite her education and aspiration, Kalyani's body falls prey to that most banal and brutal of developing world diseases: tuberculosis.

*

Quota boys, trainee-nurses with TB, street urchins selling ten-rupee balloons: Along with the immigrant, the call center agent, the sex worker, and the Coolie, these are figures that, as Rachel Lee reminds us, belong to "the category of the not-quite-human."14 The question is, does She Will Build Him a City's focus on the ineluctable corporeality of these not-quite-humans' bodies in any way restore or revive their humanity? And is the elite, Anglophone author, Jha—Chief Editor of The Indian Express and himself a resident of utopic-dystopic Gurgaon—in a position to offer such a recuperative effort? Or is his social-critical impulse, like Man's ostensibly charitable one, simply the other side of a murderous coin?

Not since Rohinton Mistry's A Fine Balance (1995), in which tailors Ishvar and Om end up amputated and castrated, respectively, has the caste-marked body been subject to this kind of violence in the Indian English novel: from fantasies of Balloon Girl's dismemberment to a brutally visualized gang rape of a low-caste girl, Nidhi, by her lover's brother and friends, who leave her for dead before going to eat Chinese food at The Leela, one of Delhi's posh hotels. To return to the epigraph, this is "devouring Coolie bodies," all right, but in far more literal terms than Tabish Khair probably had in mind.

In Babu Fictions (2001), Khair proposes a heuristic distinction between India's Coolie and Babu classes, separated both socio-economically and linguistically. The former is a vernacular class of "economically deprived, culturally marginalized, and, often, rural or migrant-urban" subjects. The latter is an urban, cosmopolitan Anglophone class Khair describes as "Brahminized and/or westernized." Khair's primary argument is that Babu fictions, written by "diasporic [or] stay-at-home Indians" (like Jha) could not possibly translate or represent the realities of "Coolie" lives.15 Rather, Babu writers inevitably engage in an Orientalizing ventriloquism of subaltern Indians for imagined western addressees:

. . . the measure of the success of an Indian English novel is not . . . its reception and sale in India [but rather] the hard fact of its sale all around the (Eurocentric) world largely based on the so-called literary quality of the writing [ . . . ] and a belief in its ability to represent India and Indians.16

Khair has recently been at pains to clarify that his argument was not about the English language used by Babu writers, but rather about the social class to which they belong.17 Babu Fictions, however, belies this claim, in that its critique proceeds from the assumption that English is not a living, "spoken language"18 in India and thus cannot hope to have purchase on Indian truths.

In the decade-plus since Khair's polemic, the Indian Anglophone novel has become far more self-reflexive about its putative alienation from the overlapping social formations of vernacular subjects and Coolie classes. Adiga's The White Tiger—in which chauffeur-turned-entrepreneur Balram Halwai slyly opens his first letter to Wen Jiabao with the note, "Neither you nor I speak English, but there are some things that can be said only in English"19—is a good example of this progression, though one that, as Snehal Shingavi points out, still fails to produce a progressive critique of caste.20 Much contemporary criticism thus centers on the critical effects of the Indian Anglophone novel's heightened, ironic attentiveness to language and, relatedly, a "renewed relationship between English and the vernaculars" in the Indian literary sphere.21 The question, at last, is not whether or for whom the English novel can "represent India and Indians" but rather how that representation accounts for and metabolizes English's vexed historical legacy, its significance as a mechanism of social advancement, and its symbolic resonance in debates that politicize language in lieu of politicizing caste and class.

Khair's "Coolie" also returns us to the related discourse on the racialized "coolie" in Asian American criticism, a figure representing, in Colleen Lye's well-known argument, a "biological impossibility and a numerical abstraction, whose social domination means that the robust American body will have disappeared."22 Glossing Lye, Eric Hayot adds that debates on Chinese exclusion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries signaled fears that "we (Americans) would all become coolies."23 The (impossible) rice-eating coolie body signaled America's (unthinkable) Asian future. To what extent, then, does the backward-caste Coolie body in She Will Build Him a City signal the backwardness of New India's future? Do the novel and its Babu-writer devour Coolie bodies in ways that reduce Coolie lives, or do they make visible the at once impossible and urgent project of representing Coolie life-worlds?

In the context of these discussions, She Will Build Him a City emerges as a critique of the premise of linguistic veracity—whether in English or the vernacular languages—as a tool of literary capture in the realist mode. The novel matches its somatic focus with a kind of hallucinatory wordlessness. When Man brings Balloon Girl and her Mother to his Apartment Complex in New City and invites them to shower in his palatial bathroom, "Neither mother nor child says a word" (45). Later, he feeds them, allows them to sleep in his air conditioned guest room, and watches them as they do, silently examining the crevices in their heels. He tips the Taxi Driver who brought them to his apartment "for not speaking throughout the ride, for not asking any questions" (46). By novel's end, we learn that a woman named Kahini is at the nexus of the three stories: daughter to Woman, former lover to Man, and mother to aborted Orphan/Child. Her name signals the Hindi word kahaani, or story, and yet she, the enabler of the story, speaks not at all. Finally, the elite Babu body's failure to speak the violence it enacts is also subject to critique. Over and above having committed the unspeakable rape and murder of the Balloon Girl-child, Man's body confounds him with its seeming imperviousness: "IF THIS ACTUALLY HAPPENED ... HE SHOULD HAVE SIGNS, SYMPTOMS ON HIS BODY ... TRACES OF HER BLOOD ... TISSUE UNDER HIS NAILS ... " (187).

In the New India of 2015, in a country that seems to have descended, once more, into the ordinary brutality of caste, class, religious, and communal strife, in the wake of the Dadri mob lynching, and the Hindutva fetishization of cow-bodies over human ones, Jha's She Will Build Him a City re-asks questions that have been and must continue to be central to (South) Asian Americanist and Anglophone literary critique. Whose bodies travel through the world unmarked, without acquiring traces of blood, tissue under the nails? How does the elite body register the marks of its encounters with subaltern Others? Is the racialized, caste-marked body always already a non- or posthuman one? Against the now-familiar preoccupation with the question of the speaking subaltern, Jha gives us subaltern, Coolie bodies, whose violation, cannibalization, and devouring ultimately trumps the critical "anxiousness of biological embodiment,"24 by pointing instead to the fundamental inhumanity of the biological human.

Ragini Tharoor Srinivasan is a doctoral candidate in Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. Her current project, After New India: The Returnee, the Call Center, and the Anglophone Encounter, is a literary and cultural study of contemporary discourses on Indian globality. Ragini is also an award-winning, syndicated journalist with work published in venues across the United States, South Asia, and the U.K.

References

- Tabish Khair, Babu Fictions: Alienation in Contemporary Indian English Novels (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 117.[⤒]

- Raj Kamal Jha, She Will Build Him a City (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 152. Hereafter cited internally.[⤒]

- Many thanks to Christopher Fan for inviting me to be part of this conversation nonetheless. See Colleen Lye, "In Dialogue with Asian American Studies," Representations 99 (Summer 2007): 3-4.[⤒]

- Rachel Lee, The Exquisite Corpse of Asian America: Biopolitics, Biosociality, and Posthuman Ecologies (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 12.[⤒]

- A. Aneesh, Neutral Accent: How Language, Labor, and Life Bcome Global (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 14.[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (New York: Routledge, 1981/1983), 177.[⤒]

- Ibid., 173.[⤒]

- After drafting this essay, I read an instructive article by Mrinalini Chakravorty on postcolonial dystopian fictions, which provides another vocabulary with which to approach Jha's text. Postcolonial dystopias as she defines them "turn on a negative dialectics ... that shuttles between thick scenes of grotesque-yet-mundane material damage and their more stylized or aestheticized translations into delirium" (268). Such novels, including Indra Sinha's Animal's People (2007) and Jeet Thayil's Narcopolis (2012), derive their "dystopian force ... from a repudiation of humanity itself" (271). Where Jha's novel seems to diverge from the form of the postcolonial dystopia as Chakravorty defines it is in its retention of a certain escapism associated with the magical realist novel—for example, in the romantic and occasionally comedic story of Orphan's adoption by Ms. Violets Rose/Love Stories. See Mrinalini Chakravorty, "Of Dystopias and Deliriums: The Millennial Novel in India," A History of the Indian Novel in English, ed. Ulka Anjaria (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 267-281.[⤒]

- Ulka Anjaria, "Realist Hieroglyphics: Aravind Adiga and the New Social Novel," Modern Fiction Studies 61.1 (2015): 115.[⤒]

- Ibid., 121-122.[⤒]

- Ibid., 130.[⤒]

- Ibid., 123.[⤒]

- Ibid., 115.[⤒]

- Lee, 20.[⤒]

- Khair (2001), 5, 21.[⤒]

- Ibid., 59.[⤒]

- Tabish Khair, "In No Masters' Voice: Reading Recent Indian Novels in English," in The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium, ed. Prabhat K. Singh (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), 55-61.[⤒]

- Khair (2001), 122-123.[⤒]

- Aravind Adiga, The White Tiger (New York: Free Press, 2008), 1.[⤒]

- Snehal Shingavi, "Capitalism, Caste, and Con-Games in Aravind Adiga's The White Tiger," Postcolonial Text 9.3 (2014): 14.[⤒]

- Ulka Anjaria, "Introduction," A History of the Indian Novel in English, ed. Ulka Anjaria (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 12.[⤒]

- Colleen Lye, America's Asia: Racial Form and American Literature, 1893-1945 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 57.[⤒]

- Eric Hayot, "Chinese Bodies, Chinese Futures," Representations 99 (Summer 2007): 103-4.[⤒]

- Lee, 212.[⤒]