Twin Peaks: The Return – Allegory and Dislocation

This summer, in an abbreviated but still smoldering Slow Burn, Len Gutkin, Benjamin Parker, and Michaela Bronstein discuss David Lynch's Twin Peaks: The Return.

Allegory is Twin Peaks's most flagrant risk and its most resonant pleasure. If we find the show stupid or ridiculous, a bathetic imbalance in allegorical structure is likely to blame: the cosmically ordained connection between the atom bomb and small-town domestic abuse offered in episode eight, for instance, can't exactly be taken with a straight face. If we worry that its most disturbing elements—incest, rape, and a great deal of murder—are (merely) exploitative or are dealt with in a morally unserious manner, we might fault the allegorical reduction of psychology to demonic possession, with its attendant constriction of moral agency.1 But allegory is also the basis of Twin Peaks's concentrated poetry, its singular capacity to evoke (rather than merely propose, like the rest of television) a world of infinite, magical dread just beyond or beneath this one. The show can induce a kind of lingering low-grade psychosis, a sensation of de-realization that brings it closer to magical rite than to art or entertainment. As Sarah Nicole Prickett says, "I resent it. It takes over my mind."2

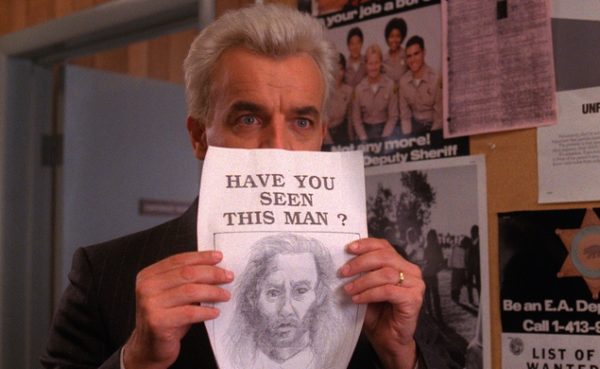

That one's mind can be taken over is, as it happens, one of allegory's signal presuppositions. As Angus Fletcher puts it in his landmark 1964 Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode, in allegory "a man is possessed by his daemon...[t]he increase of daemonic control over the character amounts to an intensification of the allegory."3 In the second season of the original Twin Peaks, demonic control is introduced as, specifically and explicitly, a problem for realism. Agent Cooper explains that the letters found under Laura's fingernails show Leland spelling "BOB"—"a signature on a demon self-portrait." Sheriff Truman: "Now this BOB can't really exist; I mean, Leland's just crazy, right?" Ambiguity is maintained throughout the rest of the episode. Dying of a self-imposed head-wound, Leland offers an account of what might be schizoid delusion, self-exculpatory fantasy: "I killed my daughter. I didn't know....I was just a boy. I saw [BOB] in my dreams. He opened me, and I invited him in."

Back then, we were still welcome to read the allegorical correspondence between BOB and Leland as the symbolic expression of a mental fact otherwise explicable in purely psychological terms. By the end of Season 2, though, with BOB inhabiting Cooper, such a reading is no longer sustainable. Cooper's infection converts Twin Peaks into allegory tout court. As Fletcher puts it, "a very large number of allegories are...based on the idea that the hero must be kept away from any contact with evil, otherwise he will pick up the evil illness."4 The Return depicts a world in which such contagion is absolutely real. "Don't touch him! Stay away from that body," as Good Cooper says to Sheriff Truman after Bad Cooper gets shot.

Fletcher's theory of allegory shows why the slippage between psychology and daemonism is available in the first place. In short, by the nineteenth century the allegorical self-splitting earlier expressed in Christian psychomachia (in which a host of personified vices and virtues vie for ascendency) had been transformed into doppelgänger narratives invested with what cannot but, to us, look like proto-psychoanalytic insight. As Fletcher says,

When the allegorical author divides his major character into two antithetical aspects, he is bound to create doubled stories, one for each half. The fact is, however, that the antitheses on which the...double is based are always antitheses of good and evil. They do not escape from their dualistic moral heritage. They allow for the simultaneous unfolding of more than one plot of similar form, and this has an inevitable allegorical effect. Psychological overtones plausibly overlay this iconographic intention.5

The condensation of a Manichean moral cosmos into involuted psychological fable is one of the achievements of Gothic fiction from James Hogg's The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824) to R.L. Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) and beyond. Gothic doubling would persist in the most overtly allegorical of the high modernists, Franz Kafka; as one critic puts it, we might think of "the rude awakenings, invasions, and transformations of Kafka's fictions as so many dissembled variations on the classic Doppelgänger tale."6

Twin Peaks's idiosyncrasy is to release the expansive dramatis personae of older forms of allegory from their containment in modernist psychological fable. As if offering an equation for this process, an early episode of The Return shows FBI Director Gordon Cole's (David Lynch) office decorated with a poster of Kafka adjacent to a photograph of a mushroom cloud—perhaps the very cloud from which, in episode eight, BOB first emerges. The successive phases of the history of allegory outlined by Fletcher co-exist in Twin Peaks with a level of explicitness that seems almost like its own account of the mode. "Doppelgänger!" the Man from Another Place (Michael J. Anderson) says to Cooper in the Black Lodge. The Black and White Lodges, obvious signals of Twin Peaks's "dualistic moral heritage," are switching-stations in which aspects of allegory (good and bad daemons; doubled selves; Freudian fables) co-exist or are transmuted one into the other.

As everywhere in Lynch—think of Diane Selwyn's fly-blown corpse in Mulholland Drive, or Renée's dismembered limbs, glimpsed only on video and in traumatized flashback, in Lost Highway—The Return's fantasias of psychic dispersal and depersonalization are occasioned by a dead body. Two, in fact; in the first episode, police officers discover librarian Ruth Davenport's head has been jammed onto the body of an anonymous man who, we later learn, is somehow the long-dead Major Briggs. School principal Bill Hastings, whose prints are all over Ruth's apartment, says he killed Ruth in a dream but not, he swears, in real life. There's every reason to think, towards the beginning of the show, that the Davenport murder will provide the central mystery to be uncovered. In this scenario, Hastings's "dream," some version of which we are watching, would be a defensive mechanism spinning off surreal distortions disguising and transmuting a murderous act. This, after all, is how both Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway often get read—they offer us oneiric transformations of some originary, brutal event presumed to have "really" happened. This structure, Fletcher tells us, is in fact primordial for allegory. He traces it to the story of Leontinus in Plato's Republic:

The story is, that Leontinus, the son of Aglaion, coming up one day from Piraeus, under the north wall on the outside, observed some dead bodies lying on the ground at the place of execution. He felt a desire to see them, and also a dread and abhorrence of them; for a time he struggled and covered his eyes, but at length the desire got the better of him; and forcing them open, he ran up to the dead bodies, saying, "Look, ye wretches, take your fill of this fair sight."7

As Fletcher says, "At the moment when the paralytic state breaks, a splitting of consciousness occurs, and Leontinus as it were separates the actions of his eyes from those of his true self; he displaces the guilt of the act onto them, and to do so he employs a central figure of allegory, personification."8 Lynch's obsession with fugue states, with doubles and alter-egos, and with the real of the corpse makes Plato's anecdote a kind of pre-Freudian interpretive key to his work.

But when, halfway through the season, Hastings suffers a head explosion (there's no other word for it) at the hands of a spectral hobo, the defensive dreamwork interpretation, already rather tenuous, becomes totally untenable. Who, after all, dreamed the hobo? When Gordon Cole describes his "Monica Belluci" dream to Tammy and Albert—"We are like the dreamer who dreams, and then lives inside the dream...But who is the dreamer?"—it's hard not to suspect that we are being offered something like the solution to a riddle, particularly when the phrase is re-played, at slow speed, during the penultimate episode (accompanied by Cooper's face eerily super-imposed on the action). Laura Miller proposes a version of the dreamwork theory to account for the final episode, in which Cooper becomes "Richard" of Odessa, TX: "What we've seen so far, over 48 episodes and more than 25 years, has been the dream of a man named Richard, a man who lives a long way from the misty, haunted forests of northeastern Washington state."9 This interpretation can be made internally plausible, but the problem is that it doesn't really explain anything. The Return updates the conventional dream vision—a time-honored way of framing allegory, as Fletcher points out10—with various metafictional convolutions, but unlike in a tradition of literary metafiction practiced by figures like Muriel Spark, Italo Calvino, and John Barth, this isn't really the point. Lynch's concern is not, as the metafictionalists' arguably is, the metaphysics of fictionality. The Wizard of Oz isn't "solved" when it's revealed that it's just a dream. "Who is the dreamer?" is a red herring. What matters is what's in the dream.

What the defensive dreamwork interpretation gets right is the emotional situation. Lynchian surreality is a tactic for managing affects that would otherwise be too much to bear.11 Fletcher speaks of the "withdrawal of affect" which "sets the systematic, unfeeling tone of allegories."12 The stunned coldness of much of The Return can be accounted for in part by its amplification and elaboration of the allegorical material that, in the original Twin Peaks, competed for space with mimetic realism in the key of soap opera. But in some of its strangest and most powerful passages, The Return summons dimly remembered soap-operatic forces to disrupt its own allegorical machinery. In a romantic denouement whose belatedness is its whole point, Norma and Ed finally get back together. Ed: "Will you marry me?" Norma: "Of course." We get a shot of the diner against the mountains, then a lingering shot of clouds moving against the sky; all the while Otis Redding is singing "I've been loving you for too long," which erupts into the show like a message from another world, where humans live.

If Ed and Norma's reconciliation offers, sort of, the consolations of comedic resolution, the long-awaited return of Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn) reminds us that this show used to be about things like jealousy and betrayal. In a long, brilliant, Brechtian scene distributed over several episodes, Audrey and her husband Charlie (Clarke Middleton) argue over an intricate romantic entanglement. Who knows what they're talking about? But the mutual emotional cruelty, the histrionic exaggeration, and the weirdly static physical postures all suggest outtakes from some parallel version of Twin Peaks in which the rules of melodrama still mean something. Fenn's self-alienated performance, like an imitation of daytime TV acting, is one of The Return's most wrenching dislocations. "I feel like I'm somewhere else," Audrey says, through tears. "Have you ever had that feeling, Charlie?...Like I'm somewhere else and I'm somebody else." Audrey is bringing the soap-opera, but she doesn't know where to put it.

Indeed, whenever expressions of emotional intensity are called for, depersonalization ensues. "I'm not me. I'm not—I'm not me," Diane says to Gordon, Tammy, and Albert, right after she tells them that Cooper raped her and right before she tries to assassinate them. Rosenfield and Preston shoot first; Diane grimaces, flickers, and disappears. "Wow," Tammy says. "They're real. That was a real tulpa." Tammy's question reprises Sheriff Truman's about BOB, in 1991 ("Now this BOB can't really exist?"), but with a difference: of course they (spirits, doubles, demons) are real. That one's self can coincide with, or become infected by, one's double or tulpa or whatever isn't a metaphor for depersonalization—it is the cause of it. "Who am I supposed to trust but myself? And I don't even know who I am. So what the fuck am I supposed to do?" as Audrey puts it, not unreasonably. Having resuscitated an extremely active, super-populated allegorical system while nevertheless remaining a work of modernist psychologism, The Return reaches an impasse. The pregnant undecidability between, for instance, BOB as supernatural villain and BOB as expression of all-too-human forms of evil cannot survive the endless multiplication of (and ever-increasing agency attributed to) the allegorical dramatis personae. The show risks becoming an extremely chilly, abstract superhero movie.13

So that's what it does. The introduction of green-gloved Freddie, a 23-year-old Londoner sent to Twin Peaks because of a White Lodge dream-vision and equipped with a super-power—"Your right hand will then possess the power of an enormous pile-driver"—is a farcical deus ex machina introduced to dissolve an allegorical system become over-grown. Miller rightly calls this development "sarcastic."14 How will Dark Cooper/BOB be defeated? The kid with the glove will punch him real hard. (Cooper: "You did it, Freddie!") As Fletcher says, "The 'god from the machine' enters upon action blocked by an impasse and breaks this impasse in a manner beyond human strength."15 In The Return, the impasse is at once plot-based (how can you kill Satan?) and modal; allegory of this sort eventually becomes an obstacle to psychological interest. Dispatching it with Green Glove is a clever move, but also risky, since it seems to take seriously the charge that the full-throated revival of allegory is fundamentally unserious.

Freddie, having cleared the ground, isn't heard from again. The final episode opens with nine minutes of efficient Red Room exposition—Dark Cooper fades into flames; Dougie is grown from a golden seed ("Where am I?") and thence returned to his family; Cooper and Diane wander out of the red curtains and into the world—but the remainder of the episode feels like it takes place in a universe that, while still free from the normal constraints of space and time, is totally cut off from the Lodges and their magical personnel. By minimizing, in its final movement, its allegorical apparatus, The Return also forfeits some of the affective protections afforded by the dreamwork. The final episode of The Return is the bleakest thing in Lynch's corpus, and one of the best. It taps a vein of primordial sorrow running though all of Lynch's work. The suffering Sarah Palmer of The Return is this sorrow's rawest emblem. "Sorrow," actually, is probably too soft a word for the affect undergirding this episode; ditto "melancholy." What's the right word for this devastation? "Misery" is too busy, too suggestive of activity: The Return's long takes and silences all tend towards stasis. "Garmonbozia," perhaps. In the forlorn sex between Cooper and Diane, in which Diane seems to erase Cooper's face with her palms; in the long black drive from Odessa, TX to Twin Peaks, WA, in which "Richard" (Cooper, Good and Bad in one) takes Carrie Page (AKA Laura) to the Palmer residence; in the disoriented lurch with which Cooper/Richard (the grain of Dougie coming through the wood) asks, "What year is it?"; in the cry from the house ("Lauuura") alerting Carrie/Laura to her own death; in Carrie's scream, which is Laura's scream, which is Lynch's scream, The Return ends on a note of mourning indistinguishable from the most absolute horror. I can't resolve the twisted ribbons of plot, but the wreckage of this final hour depends above all else on the cumulative dislocations that have preceded it. "I don't even know who I am. So what the fuck am I supposed to do?"

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

Len Gutkin, "Genre Mistuned" (8.10.17)

Ben Parker, "Around the dinner table, the conversation is lively" (8.17.17)

Michaela Bronstein, "Allegory as Alibi?" (8.25.17)

Ben Parker, "Going off the Grid" (10.4.17)

Michaela Bronstein, "The Anxiety of Spectatorship (10.6.17)

Len Gutkin is a Junior Fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows and a scholar of twentieth-century literature and film. His articles and review-essays have appeared or are forthcoming in ELH, Contemporary Literature, Literature Compass, Amerikastudien, The Times Literary Supplement, Boston Review, and elsewhere.

- In different ways, Ben and Michaela each identifies the show's allegoricality as vulnerable to aesthetic failure. As Ben says, "The stupidest part of the new season, then, is the implication that the nuclear bomb somehow preordained the rape of Laura Palmer." Michaela: "There's something a little bit ugly in seeing Laura Palmer's high-school face emanating, like BOB's, from the aftermath of that catastrophe—as though she is now an allegorical incarnation of good to counterbalance evil rather than a complex individual....The series has always walked the line between resonant exploration of the non-realist borders of subjective experience and tired imposition of static allegory."[⤒]

- Sarah Nicole Prickett, "Theme and Variation" (Artforum) [⤒]

- Angus Fletcher, Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2012), 47, 48, emphasis deleted. [⤒]

- 210.[⤒]

- 185.[⤒]

- Andrew Weber, The Doppelgänger: Double Visions in German Literature (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996), 326.[⤒]

- Qtd. Fletcher, 227.[⤒]

- Fletcher, 227-28.[⤒]

- Laura Miller, "In Twin Peaks' Finale, Dreams Have A Cost" (Slate) [⤒]

- A "stock beginning of a late medieval allegory is likely to be the hero's awakening into a dream vision" (350).[⤒]

- In this respect, I agree entirely with Ben: "Lynch is not exposing the real but our tortured accommodation to it."[⤒]

- Fletcher 290.[⤒]

- For Fletcher, Christian allegorical psychomachia is a refinement and psychologization of mythic gigantomachia (151). In contemporary popular culture, the most overtly allegorical works are precisely battles of giants: superhero franchises, but also, for instance, Buffy the Vampire Slayer.[⤒]

- Laura Miller, "In Twin Peaks' Finale, Dreams Have A Cost."[⤒]

- Fletcher, 55.[⤒]