Twin Peaks: The Return – Going off the Grid

When I was a kid, I loved the maps of imaginary places that would fold out of books like The Hobbit, The Phantom Tollbooth, The Princess Bride, and Treasure Island. For books that didn't come with maps, I had to draw my own, although I outgrew this by the time when I read grownup books. But this summer, I was reading John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress and trying to map out on my bookmark, with childish diligence, where was the City of Destruction, where the Wicket Gate, where the Delectable Mountains. This was at the same time that the new season of Twin Peaks was coming out. Yet even though Twin Peaks—as all contributors to this forum have noticed—is itself a kind of allegory, no such mapping is possible. Even though the opening credits welcome us on our way into Twin Peaks (population 51, 201), we never find our way around the town. Of course it would be obtuse to ask where precisely the extradimensional Red Room is located. But the more mundane Great Northern Hotel is just as unmoored from any orienting position. One might even read the last scene in the series as Cooper and Laura Palmer arriving at the wrong address.

I wrote about Lynch's version of allegory last time as "not a rich superstructure of meaning but only the topography of a nihilistic self-reference," where characters were put through the paces of the bleak, hollowed-out demands of excessively signifying figures (e.g. imperious colossi like "the Arm" or Mulholland Drive's "The Cowboy"). The topography I had in mind was the feeling of being "in" narcissism, where surely nothing points outside of itself, but only collapses into the dense gravity of an acrid, private pathology. By contrast, in The Pilgrim's Progress, the prominent markers in the landscape, indicating Good and Evil, are almost like the animatronic fixed attractions on an amusement park log flume ride. Their placement in sequence is itself the simple narrative whose sense is never in question. Lynchian allegory, though, does not reference another order of meaning (not even a legible, resolved "story"), but substitutes itself (its intensities) as a compelling if not coherent process. One way to think about this is as the difference between the latent meaning of a dream, whose elements could be finally rationalized, and the distorting activities of the dream work. Properly Lynchian allegory gives a kind of symbolism effect, of outsized Meaningful Figures, but attaches these figures to an arbitrary landscape, hinged awkwardly onto our world. The problem, then, with the nuclear explosion in Part 8 is not that Lynch was being too allegorical—simultaneously too reductive and too enormous, as Len implies—but that he was giving explanations at all. Lynch was not following his own rules.

To live in the Twin Peaks universe is to be vulnerable to such a failure of meaning in "reality" itself, as with Audrey's apparent psychosis and possession by her own acousmatic anthem—or, what is not much better, to be interpellated by a stupid and tacky destiny, as in the case of Freddie's rubber-gloved hand. The misdirection we see in the Cooper/Dougie plot is another version of this failure of symbolism. For Cooper's police work was never the coordination of salient semiotic items (clues), out-of-place in this order of meaning but strikingly in-place in another sequence. Cooper's "method" resembled the laying of stones alongside one another in land art: accretive and generative process rather than decoded solution.

You get a sense of this in the parody Kyle McLachlan appeared in when he hosted Saturday Night Live in 1990. The joke is that, even when the real killer (Leo Johnson, played here by Chris Farley) has been arrested, Cooper keeps drawing out the investigation with his whimsical methods ("Tonight we'll stake out the graveyard disguised as altarboys"). In the actual series, the reveal that Leland is the killer is, in Hegel's expression, "shot out of a pistol." It doesn't make retrospective sense of the story lines we had been studying for clues and leads. It doesn't amount to a prosecutory "case" that Cooper had been building up. Just so, at the end of The Return, when Dark Cooper is finally defeated, the credit for this goes to a confluence of minor players rather than a master plan that Cooper has orchestrated to completion.

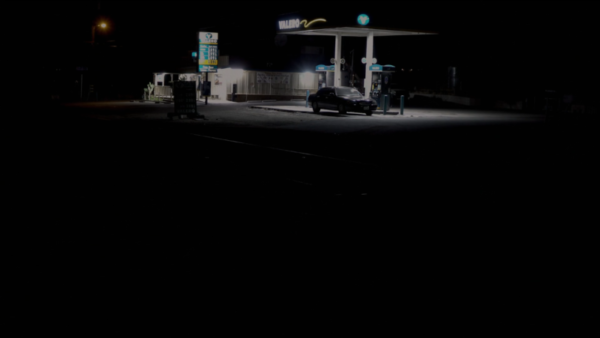

Dougie's interminable "stuckness" is indistinguishable from Cooper's own looping, tangential investigative approach. He too is pure delay and contingency. Dougie might then be thought of as a commentary on Cooper, not just a detour. One difference would appear to be that Cooper, once he wrests back command of his body, springs into dynamic action, flying to Washington, crossing through time, driving 430 miles, slipping into another course of reality, then driving back from Odessa, Texas to Twin Peaks. That is a lot of credit card miles, certainly, but is Cooper any less "stuck" than Dougie in the final scene? The map he traverses is simply not a meaningful one, as we see in the brief scene at the Valero gas station. This minimalist, generic stopover is the only sense we are allowed of there being anything at all in between Washington and Texas except the yellow line of the night highway.

*

In this last episode, Cooper, back in the Red Room, takes on two pieces of surrogate parenting business. Having shocked himself back to selfhood by sticking a fork into an electrical socket, he summons the trinkets and magic of the weird realms to sprout another Dougie, who returns, loveably oblivious, to the bosom of his family. Of course no one notices that he is an unconvincingly flat (if "family friendly") replica of a person, because it's Las Vegas. After this light Baudrillardian fare, Cooper is tasked by Leland Palmer—seemingly frozen for all time in a clenched grimace, like another Ugolino—with finding his daughter. If restoring the father to the Jones family proved absurdly simple—just conjure a duplicate person!—the mission to restore Laura to her family unweaves most of what I thought had "happened" on the show, also unmaking any imagined renderings of a fragmented and insufficient map of Twin Peaks the show (or Twin Peaks the town).

In my last essay, I wrote that it was "impossible to foresee how Cooper's return from the Black Lodge (the motivating event for the whole season) will respond to the still-unresolved Laura Palmer story, or what would even count as a response." The first response is an attempted rescue. Cooper travels back in time (into the film Fire Walk With Me) and attempts to lead Laura by hand away from the destiny awaiting her in the woods that night. But like Eurydice, she vanishes again into the shadows. The next response is attempted repair. Cooper picks up Laura's trail in Odessa, Texas, where, as "Carrie Page," she has apparently drifted or been transplanted into a hard, neglected life, like one of those blown-out tire treads that litter the Texas highways. To quote Bernard Williams, her life is in "a state of dereliction from which large initiatives and a lot of luck would be needed to get it back to anything worth having."1

But we have no authority to say whether or not this dereliction is owing to what happened to Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks. The eventual failure to get "the little girl who lives down the lane" back to her mom—while heartbreaking—is for me secondary to the question of what life Cooper has tracked here. Carrie Page is played by Sheryl Lee, but then, so was Maddy in the earlier seasons. What we are still left with is an incomprehensible transformation, stranded between worlds, and plunged into the wailing and shrieking night. (In this sense she is closer to Sarah Palmer.) I do not have the Lynch/Frost skeleton key, so I can't say where or when this all takes place, but the ending seems to me just as much a possible beginning: the question of "what would even count as a response" to Laura's life might be best answered by a response (left hanging) to a life that doesn't have her history, her name, not even her world in common.

*

I wrote that "one does not expect from Lynch an ending like The Wizard of Oz," but basically this is what we get. To begin, the defeat of Dark Cooper, which depends on the arbitrary and dropped-in device of Freddie's green rubber glove, recalls the sudden cleaning-supply death and anticlimactic condensation of the Wicked Witch of the West, who melts into a steaming pile of rags after a bucket of water is tossed upon her. Shortly after the Witch's dispatch, the Wizard's first attempt to get Dorothy out of Oz is a plan to bodily cart her off in his hot air balloon, which misfires when her little dog jumps out and she disembarks. This is like Cooper's failed attempt to pull Laura physically out of the (now black and white) Fire Walk With Me sequences. The next attempt to save Dorothy dissolves reality itself, when the clicking of the ruby red slippers vanishes the Oz world of color. In Twin Peaks, Cooper does manage to jump tracks onto another reality, but we find there really is "no place like home." Not in the (doubtful) sense that other places just don't stack up with Kansas, but in the sense that home is not a real place, being only a depleted uncanny edifice whose homeness has been scrubbed out of the particular time-world we have been shunted onto.

If the new season is a "return," we cannot say in the final scene where we have been returned to or what names and places still hold. Cooper has apparently reset the map in some way, like an automatically-generating scenario in a computer game, recycling but redistributing the elements of a limited mythology. One has hesitated to call Twin Peaks a franchise reboot, because the original cast is continuing the original story, but the finale is something like a reboot within the continuum of the original story. It is as if the never-should-have-been-shown-to-children Fairuza Balk sequel Return to Oz, where Dorothy is given electroshock treatment and is transported to an unrecognizable trash-Oz with knockoff companions, had been stitched into the Judy Garland film. Twin Peaks ends not with the belabored climaxes (prepared by long stages) or the elaborate reveals one finds across "quality TV," but with the uncanny refusal of known settings. Allegory of the Pilgrim's Progress or Wizard of Oz (book, not film) type offers a map of meaningful and semi-permanent landmarks, but no history: their sense is in the ongoing present encounter of the protagonist with those features. Twin Peaks has not been like this, because its symbolism effect has never depended on the traversing of a pre-given map. The final moments of the series, though, might now be read as a kind of wringing-out of history, the reassertion or resetting of a "blank" and unresponsive environment whose meanings are threaded through a history we no longer have access to.

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

Len Gutkin, "Genre Mistuned" (8.10.17)

Ben Parker, "Around the dinner table, the conversation is lively" (8.17.17)

Michaela Bronstein, "Allegory as Alibi?" (8.25.17)

Len Gutkin, "Allegory and Dislocation" (9.16.17)

Michaela Bronstein, "The Anxiety of Spectatorship (10.6.17)

Ben Parker is assistant professor of English at Brown University, where he teaches Victorian literature. He has written about music, film, and fiction for Film Quarterly, n + 1, Los Angeles Review of Books, New Literary History, and Novel: A Forum on Fiction.

- Bernard Williams, Shame and Necessity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 70.[⤒]