Sex and the City: Lakshmi, July 10

Williamsburg, Brooklyn

Genre Trouble, or, Being Miranda

When Ari asked me why I hadn't watched SATC before, anxiety seemed like the most obvious answer. During the show's run in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I was a baby butch in high school, and then a Catholic women's college (i.e. lesbian heaven), in Chennai, India. It's not that I wasn't interested in femininity—I was very interested—but I desired it in others, in the Other, not for myself. Sex and the City threatened to make explicit the message I was already getting from the girl friends who refused to acknowledge that they could also be my girlfriends, or suggested that what we did in dimly lit bars and stolen moments of intimacy was not intimate at all. The message said that femininity was for straight people, and that it was a lesson I needed to be taught so that I could join them.

In other words, long before I'd seen it, Sex and the City stood apart for me from other entries in the contemporary romcom canon because it seemed peculiarly pedagogical, and I didn't think I wanted the schooling it offered. I would be educated into aspirational womanhood in the global city; I might discover that my desires didn't really exist and that the sex I was having was bad sex or wasn't sex at all. Twenty years later, this tutelage has been reworked in countless shows—Girls and Broad City, which I've loved and loathed, along with Gossip Girl and The Carrie Diaries and Being Mary Jane and so many more—but Sex and the City remains a cultural flashpoint, the origin story for which these others constitute the hungover aftermath.

Sex and the City created a set of narrative expectations, habits of thought that allowed us to consume the disorder of neoliberalism as a narrative, and it did so in large part by inviting a kind of schematic self-identification. When we are asked to identify as "a Charlotte," or "a Samantha," or "a Carrie," we are being given a model on which to build our individualized expectations of the good life. These characters are vessels to pour ourselves into, to learn what could happen to us if we chose the wrong path. The twist, though, is that there isn't actually a wrong path for the women of SATC: they could all in their own ways participate in this utopian vision of New York, drinking their way through brunch and going shoe-shopping to ease their woes, in their differently inflected performances of femininity as consumptive capitalism. This makes sense given the cultural history of the show: emerging out of the mid-'90s, SATC gave women narratives of belonging that could account for the anxiety of freedom from the heterosexual couple form and family ties while still reproducing these modes as desirable, if perpetually deflected or deferred, structures for their lives.

But then, there's Miranda.

I'd always guessed that I was a Miranda, even without watching the show, even as a queer brown girl with Marge Simpson hair growing up in Chennai, looking at a (straight...ish) redheaded lawyer living in Manhattan. But this isn't a post about Being a Miranda. Rather, I'm interested in the moments when Miranda seems to stop being "Miranda," and become something more: a character who challenges the heterosexual programming of femininity that the show provides for its viewers, dressed up in expensive heels and great color stories. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

*

Watching Season 1 of SATC confirmed the genre expectations I had of the show. The four main characters are essentially scripts for heterosexual femininity, providing us with stereotypes for survival under the regime of biotechnologies that have granted a degree of freedom from biological risks such as pregnancy or STIs. In Carrie's New York, there are almost no people of color, poor people, or queers. But we know all these critiques of the show already, and I'm not trying to add to the tower of think pieces about the limits of SATC's representations. Rather, what I'm struck by is the extent to which—in jarring contrast to my own fears of learning to do femininity—these characters seem utterly ignorant of the fact that the social codes they abide by, despite being in many ways new, have any contingency to speak of. What jumps out at me, in other words, is the extent to which they seem blissfully ignorant of their place in the world.

In recent years, lauded shows about sexuality, gender, and intimate relationships (Transparent, I Love Dick, and Girls come to mind) have allowed us to experience the generalized anxiety collectively seeping out of us as a kind of anxiety porn. The characters in these shows endlessly obsess over their own overdetermined histories, pushing against their status as women, people of color, or religious minorities, almost to a fault. In contrast, the ladies of SATC, like the world they inhabit, seem to thrive on ignorance. Carrie, Charlotte, and Samantha, at least, seem to be blessed with a form of forgetfulness of who they were before they moved to the city, or what the city was before they arrived. Thus far, none of them seems to come from anywhere in particular or to have, say, a mother. It is a double-forgetting that they exhibit: first, of the (very recent) history of feminist struggles over reproduction, the right to work, equal pay, none of which are even remotely indexed in season 1; but also of the possibilities that these struggles held out to begin with, possibilities that these characters would seem perfectly poised to realize: that reproductive and financial freedom could facilitate a sexual revolution. What I'm saying is: with the money that they all made and spent over the course of the first season, these women could start a queer femme commune or—say—run for public office, without having to worry about paying for child care, marriages, or the emotional labor of enforced heterosexual coupling. And yet, all they do is talk about the men they're sleeping with.But these characters have to forget so that we as viewers can too, at least briefly. Then we can consume their consumerism and find through them a way to live in the precarity of disappearing state welfare and increasing costs of living, of flatlining wages and temporary work, by searching for our own Mr. Big. And yet it is precisely the pharmacopornographic regime, as Paul Preciado would put it, that they occupy—one that produced femininity (and masculinity) "as artifacts that originated with industrial capitalism and would reach commercial peaks during the Cold War, just like canned food, computers, plastic chairs, nuclear energy, television" 1—that makes their gendered position not just reproductive but endlessly reproducible to begin with. "The recent history of sexuality," Preciado continues, "appears as a gigantic pharmacopornographic Disneyland in which the tropes of sexual naturalism are fabricated on a global scale as products of the endocrinological, surgical, agrifood, and media industries." 2 As an enduring text of femininity in recent cultural history, the characters on SATC live in the Disneyland they create, teaching us about aspirational, commodified feminine desire by forgetting that there is an outside to their theme park.

All of which is to say that my anxiety about engaging with Sex and the City has finally become legible to me because I am binge-watching it at the same time as Westworld.

Westworld, not an obvious relative of SATC, is set in a dystopian near-future, where human-like robots (called "hosts") reside in a theme park modeled after a nostalgic vision of the Wild West, which human guests can visit for an expensive ticket price. Once in the park, guests are free to act out their most violent desires on the hosts, whose entire reason for existence is to serve as a canvas for the guests' journeys of violent self-discovery. The inventor who has constructed the massive park, and given life to every "host," is Dr. Robert Ford (played by a very creepy and convincing Anthony Hopkins). The creepiest thing about him is that he believes his power over the robots in his command—a power that has taken the form of subjecting them to unending rape, torture, and murder—is essentially benevolent. Dr. Ford tells his creations at multiple points in the show that he doesn't believe there is anything separating them from humans other than his generous gift of allowing them to forget the horrors they've lived through. For these lucky robots, memories of violence, suffering, pain, and loss, along with their traumatic aftereffects, can be erased with a simple swipe across a computer screen. At one point, Ford argues that his creations are to be envied, not pitied. Their lack of memory isn't their founding loss; it is, as for the characters on SATC, their most valuable attribute.

So perhaps the genre we need in order to watch SATC is in fact science fiction. Carrie's New York is Dr. Ford's Westworld, a dark Disneyland in which a carefully orchestrated group of characters continually live out the same scripts of violence masked as pleasure. In Westworld, the show's entire conceit hinges on remembering. Over the course of season 1, several hosts start to have visions unassimilable with their everyday lives, visions of violence that are memories of their previous deaths, or unexplained deeds. These scenes rupture their self-narratives, breaking them out of the scripts that they are programmed with and leading to unexpected consequences, including the potential for their own freedom. On SATC, one character shares such moments of memory and rupture, woven in with a form of misplaced or unassimilable queer desire.

Or, as Andrea observed:

*

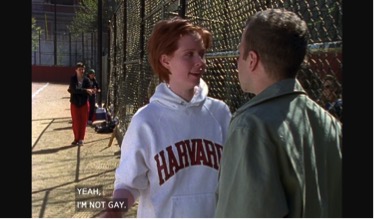

Miranda often plays the closeted queer with an open secret. She is the only short-haired, pantsuit wearing representation of anything resembling butch for the first season, and a number of scenes address her sexuality with almost campy delight. Early in the season, she is mistaken for a lesbian and continues the charade, hoping to advance her career with her new sexuality. (Spoiler alert: it doesn't work out.)

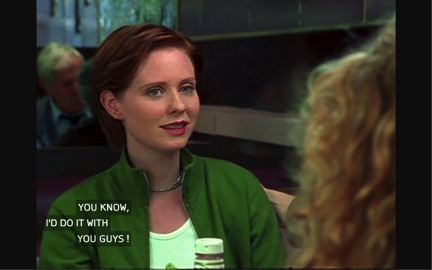

Yet as the show progresses, Miranda's desires don't seem to be so easily dismissed. At brunch one day, Charlotte is contemplating a threesome and suggests Carrie or Samantha join her in bed with her boyfriend but skips Miranda as a potential sexual partner. Irritated that Charlotte would consider breaking her vow of heterosexuality for her other friends, Miranda insists that she would sleep with all of them, and compares being left out to dodgeball selections in high school. First in her flippant dismissal of the threesome ("Guys just want to watch you be a lesbian for a night") and then in her nonchalant delivery of her complicated desire to have sex with her friends, Miranda finally looked like the closeted bisexual that I have always wanted on screen.

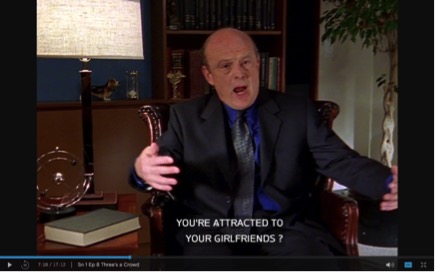

Later, she shares these desires with her therapist, a reasonable voice of heterosexuality who seems genuinely shocked by Miranda's homo desire, prompting a more melancholic rendering of the closet.

In episode 9 ("The Turtle and the Hare"), Miranda points out the obvious: that men aren't necessary for marriage, sexual reproduction, pleasure, or even conversation. She is, rather, in love with her vibrator. We live in a pharmacopornographic reality, and Miranda is the only one who occasionally seems to notice.

Like the robots on Westworld who start to realize that maybe the world they live in isn't all it's cracked up to be, by the final episodes of season 1, Miranda is no longer simply desiring her friends, she's threatening to act on it. By episode 11 ("The Drought") we know that she hasn't had sex in months. While watching Carrie's neighbors have sex one afternoon, Samantha, Charlotte, and Carrie are caught up in mechanics of their sexual encounter, while Miranda quietly warns them, almost as if to herself, that she might hump her friends. I couldn't help but wonder...what kind of show and what kind of world would that be, in which queer desire was both a warning and a promise of the future, an intimacy that develops not within the heterosexual feminine programming of gender but always in excess and its threat?

I know, I know, that Miranda is not necessarily the queer icon we need. I've also seen enough Miranda GIFs to guess where her narrative is going: Miranda gets married to a man, and gets pregnant, and wrestles with all her responsibilities as a lawyer, wife, and mother. I'm not saying she's who I want to be, or even that she'll become what I want, but instead, I'm interested in the brief scenes where Miranda questions her (and her viewers') desires for the kind of femininity that SATC is constantly marketing to us. Those brief flashes of memory offer the potential for freedom from their feminine dystopia, showing us the cracks through which we can see where their theme park ends. Of course, the reason I care about Miranda making it out, just like I care about Westworld's femme disruptions (Thandie Newton as Maeve is just stellar, FYI) is because I want them to make it out of this dystopian New York, and actually face the New York I live in. Such moments only reiterate the jarring juxtaposition that we face, watching this show today, between Carrie Bradshaw's New York that never was, and Cynthia Nixon's potential New York that could be.

The Slow Burn, v. 4: An Introduction

Ivan Ramos (Guest Post), October 1

Audrey Wollen (Guest Post), October 22

*

The Slow Burn, volume 4, will run in this space all summer. Previous summers can still be found on Post45:

2015: A Summer of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels - Sarah Chihaya, Merve Emre, Katherine Hill, and Jill Richards

2016: Summer of Knausgaard - Diana Hamilton, Dan Sinykin, Cecily Swanson, and Omari Weekes

2017: Welcome (back) to Twin Peaks - Michaela Bronstein, Len Gutkin, and Benjamin Parker

- Preciado, Paul. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. New York: Feminist Press, 2013. 99[⤒]

- Preciado 101[⤒]