Sex and the City: Audrey Wollen, October 22 (guest post)

Crown Heights, Brooklyn

DEAR DIARY,

1. My first encounter was unreal and heavy-handed, like a dream or a joke, parodic in its overt symbolism. It's difficult to believe, or remember, in retrospect. I was barely fourteen, sinking into the depths of my therapist's oversized armchair. The entire room was brown. It looked like everything—the couch, the carpet, the books—had been covered in soil, like we were buried deep underground, an office carved out of wet earth. I'm sure she had many years of schooling, but for me her primary qualification was that she had a stern bob and a movie-therapist name, like Nancy, Sharon, or Linda. She felt bad for me because I was currently suffering from a disfiguring and life-threatening disease, so she was less of a therapist and more of a gentle mother figure who nodded meaningfully when I talked, no matter what I said. I was profound just sitting there; illness does that. Our conversation was largely useless, analytically speaking, but the setting was oddly comforting, reliable. Uneventful. Until, one day, at the end of our forty minutes, she pulled out a Giant Pink Furry Box.

We paused. I took it in my hands. It was bigger than a shoe box, and hefty. The pink was a florid magenta. The fake fur was bristly and covered the entire thing, except for a bedazzled silver skyline along the cover's bottom edge. Elegant, I thought, genuinely, because I was fourteen and it was 2006 and "bedazzled" and "elegant" were not yet antonymic terms. The box opened to reveal thick pages, stacking at least fifty, maybe even a hundred, pastel DVDs in plastic pockets.

"Here," she said. "Have you ever heard of a show called Sex and the City?"

2. I was very sick, but I was also a fourteen-year-old girl, and both states were felt with equal affliction. Every life event was life threatening. "Will my mystery tumor keep growing into my chest cavity, severely limiting my ability to breathe and eventually collapsing my lungs?" lived right next to, "will the boy who works behind the counter at the independent movie theatre ever kiss me, even though I don't know his name and we have not technically spoken?" They were my twinned dramas, grave and indiscernible. This was a kind of nonhierarchical commitment to experience that I would later miss. I wanted sex just as much, if not more, than I wanted to live to adulthood. I knew very little about either, but I wanted without needing to know. They both, having sex and continuing to live, seemed vaguely unlikely anyway. Some days impossible. But I was tracking in the impossible then, knee deep in impossible, wading through it to my chemo on Fridays, girlish and muddy with it. So, after she handed me the pink furry box, I went home, and because I had no friends, no school, and nothing to do except go to the doctor and be profound for grown up strangers, I watched every single episode, all ninety-four of them, within ten days. A lot of people say Sex and the City was too prescriptive in its depiction of stifling heteronorms and bizarre codes of femininity; however, so far, I am the only person I've ever met who received the show as an actual prescription from a medical professional.

3. There was literally nothing in the world of Carrie, Samantha, Charlotte, and Miranda—I mean, Nothing—that was relevant to my life. I didn't live in New York City, I didn't have sex, I didn't date, I didn't work in media or PR or art or law, I didn't have friends, or go to parties, or pay rent, or drink cocktails. I barely left my house. It was a rapid education in the most spectacularized version of (hetero-)sexual possibility. There was only one thing I understood in the show, one small sliver of overlap in the Venn diagram of ME and CARRIE that I drew in my journal, between softly sketched portraits of a very anorexic Mary Kate and elaborate Buffy fan fiction. It was a glimmering fissure, our vulvic slit of common ground, inscribed in bubble letters: SHOES.

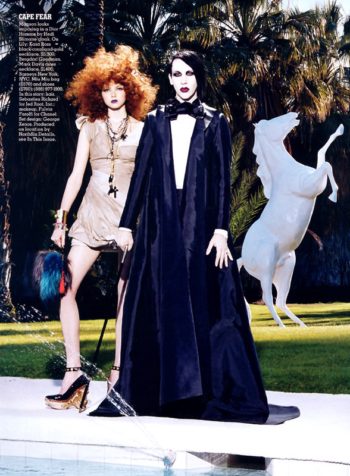

4. A brief piece of context: I am currently six foot, two inches tall, but I hit six feet at twelve years old. I was 5'10" at nine. This oversized sense of my own body undeniably underpins my erotic fixation with high heels and devotion to the women who wear them. Scrape the burnt surface of any love and you'll so often hit a soft, gelatinous layer of envy. 5. Another piece of context: when I was first diagnosed and maybe dying (the doctors were uncertain), my mother asked me if there was anything she could get me to make me feel better. I think she thought I'd ask for, like, a pedicure, or maybe an iPod. Instead, I went into my room, brought out the Lily Cole and Marilyn Manson editorial in the "Fashion Rocks" supplement of the September issue of Vanity Fair.

I pointed to the Miu Miu Baroque Wedges that Cole was wearing with a McQueen bubble-hem mini-dress next to Manson, ghostly in the Los Angeles sun, palm trees and pool glistening. "These shoes would help," I said. When they arrived in a box from eBay, they were too small, I could barely squeeze into the sharply pointed toe. They still sit on our living room bookshelf like holy objects in a home altar, patent totems of survival, desire, and gratitude.

6. In episode 9 of season 6, "A Woman's Right to Shoes," Carrie attends a friend's baby shower and is asked to remove her shoes at the door of the apartment, a femme-noir premonition of doom straight out of Daphne du Maurier. Inevitably, her new Manolo Blahnik stilettos are stolen, and she has to return home in a pair of borrowed chunky white sneakers (which are, ironically, today's trendiest shoe). When she gives the sneakers back and asks if the Blahniks have turned up, the host reluctantly offers to pay for them. Carrie gives her the price ($485.00), but her friend balks ("Come on, Carrie, that's insane") and offers $200 flat. The following exchange hinges on the shoes' potent metaphoric capacity, which, in turn, only reanimates them as fetish objects. (What is a fetish object if not an excessively effective metaphor?) "You know what Manolos cost," Carrie counters. "You used to wear Manolos." You used to be like me, a single woman, you used to have sex for pleasure and not reproduction, you used to enclose your own desire, not disperse it between husband and baby and home, you were masturbatory and joyful and frivolous, fetishistic, you had the phallus under your heel, you used to wear Manolos. "Sure, before I had a real life...Chuck and I have responsibilities now...kids, houses," says the friend. Two words (kids, houses) slice her heel off, like Cinderella's bloody-footed stepsister. These "responsibilities" are "real," and diametrically opposed to fetish, pleasure for pleasure's sake, penetrative metaphor and genital absence. She fucks Chuck, and has his babies, and doesn't need the pleasures of Blahniks anymore. "I have a real life," Carrie responds, softly, firmly. How did we suddenly end up in an ontological clash, where reality itself is up for dispute? "They're just shoes," retorts the friend, as a blonde baby gurgles, "Shh-shh-ooo," from her hip.

7. In a 1927 essay, Freud explains the nascent beginnings of a shoe fetish as being primarily triggered by the visual orientation of the floor-based infant. The small (inevitably boy) baby "peered at the women's genitals from below, from her legs up." Expecting to see a penis, like his own, he discovers something else entirely: nothing! The glorious lack of womanhood. This is a strange sort of shock: normally, one is frightened by the presence of something one didn't expect to see, not the absence of something one assumed was there. We rarely jump at empty space. However, Freud proposes that the trauma of this discovery (the nothing that was supposed to be something) causes the infant to look around in crisis, and the closest visual object is inevitably at direct eye level: his mother's feet. His mother's shoes. For the rest of his life, his erotic anxiety finds solace in the phallus-substitute of the woman's shoe: the comforting something that saved him from the maternal void.

8. The "stiletto", a tall, very thin heel, was invented in late nineteenth-century fetish communities, as part of a developing bondage aesthetic and subculture. The phallus metaphor, as explicated by Freud, is obvious, but the high heel functions on many different erotic registers. It offers a scene of precarity, balance, scale, limitation, and power: the wearer is simultaneously dominant (towering, otherworldly) and submissive (unable to walk, toppling, bound). It is a tautological sexual object: the shoe is both the cunt (penetrated by the foot) and the cock (permanently erect). The taller and thinner the heel, the higher the wearer stands, and the less likely it is they are able to move. In the 1950s, Roger Vivier invented the method of using a steel rod inside the heel, which allowed for even sharper, thinner silhouettes to hold the weight of the foot. In the late 1970s, Manolo Blahnik repopularized the stiletto and maintained its iconicity into the early 2000s, past the office-appropriate kitten and the chunky platform of the '90s. Its resurgence around the millennium was credited partly to Sex and the City and Carrie's devotion to the brand, prompting a whole generation of women to cast off the nihilistic wedge of grunge and enter into the pre-recession saccharine sexuality of the 2000s. Enter the low-rise flared jean, visible rib cage, bedazzled baguette bag, and strappy stiletto, clacking down Fifth Avenue. This was a new chapter of feminine masochism in fashion, and feminine pleasure. In a 2000 feature on Blahnik in the New Yorker, Sarah Jessica Parker says, "You have to learn how to wear his shoes—it doesn't happen overnight. But by now I can I could run a marathon in a pair of Manolo Blahnik heels....I've destroyed my feet completely, but I don't care. What do you really need your feet for, anyway?" In the same article, Blahnik quips, "I'm simply mad for extremities. I always have been. The rest of the body seems so dull to me."9. What do you really need the rest of the body for anyway? Carrie's shoes are ultimately unwearable: they exist in the realm of fantasy, physical and financial. Running in heels, another impossible thing girls do. Carrie darts like an antelope in tulle, never bleeding, blistering, or slipping into a subway grate. She spends all her money on shoes in search of a phallus that—unlike her love interests—will stick around. The extremities of femininity: the furthest most point, the detachable limb. But the viewer calls the show's bluff: no one can afford all those Blahniks, no one can run like that down cobble stones. I couldn't help but wonder: is the phallus always essentially unwearable?

10. How does my heel fetish embody a wish to become enormous, a giantess, powerful and perhaps, in that, also unfuckable? In heels, I am 6'5", minimum. I have spent the last decade or so gradually unlearning all the dried-up sexual lessons of Sex and the City, peeling them off in long, iridescent strips. I didn't get anything from the show or that therapist except a shoe fetish, but what a wonderful gift to give a fourteen-year-old girl. I used to think I wore heels to become so huge no man would touch me. These days, though, my erotics attach to a man who stands 5'9", and I blush when he tells me he likes me in heels. I am flattened with desire, crushed by his willingness to look up. I'm no longer dying, or at least, only in the same way everyone else is. My heels stand in rows by our bed.

LOVE,

AUDREY

The Slow Burn, v. 4: An Introduction

Ivan Ramos (Guest Post), October 1

*

The Slow Burn, volume 4, will run in this space all summer. Previous summers can still be found on Post45:

2015: A Summer of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels - Sarah Chihaya, Merve Emre, Katherine Hill, and Jill Richards

2016: Summer of Knausgaard - Diana Hamilton, Dan Sinykin, Cecily Swanson, and Omari Weekes

2017: Welcome (back) to Twin Peaks - Michaela Bronstein, Len Gutkin, and Benjamin Parker