Issue 1: Deindustrialization and the New Cultures of Work

This essay offers an account of one profession's attempt to come to terms with the meaning of work in a context of economic and technological flux. Bound from the beginning to the mass-production tool of the printing press, graphic design has consistently been implicated in mechanization. For early designers — even those with no known objection to machine production — the rationalization and deskilling of work were thus unavoidable practical issues. With the emergence of modernism came a new consensus around the machine, which often wedded socialist aims of freedom and equality to productive capacities unleashed by industrial capitalism. As hopes for global revolution faded, however, accelerating industrial modernization lost its utopian glow. As I will show, changes in work processes became a site of struggle for print workers in particular. By the mid-twentieth century, as the printing trades were being transformed by technological change, the design professions were being embraced by large corporations. The austere rationalism of corporate modernism soon became a steady target for discontent about the direction of the modern world. Beginning in the late 1960s in graphic design, this discontent manifested as a series of "style wars" that culminated in postmodernism.

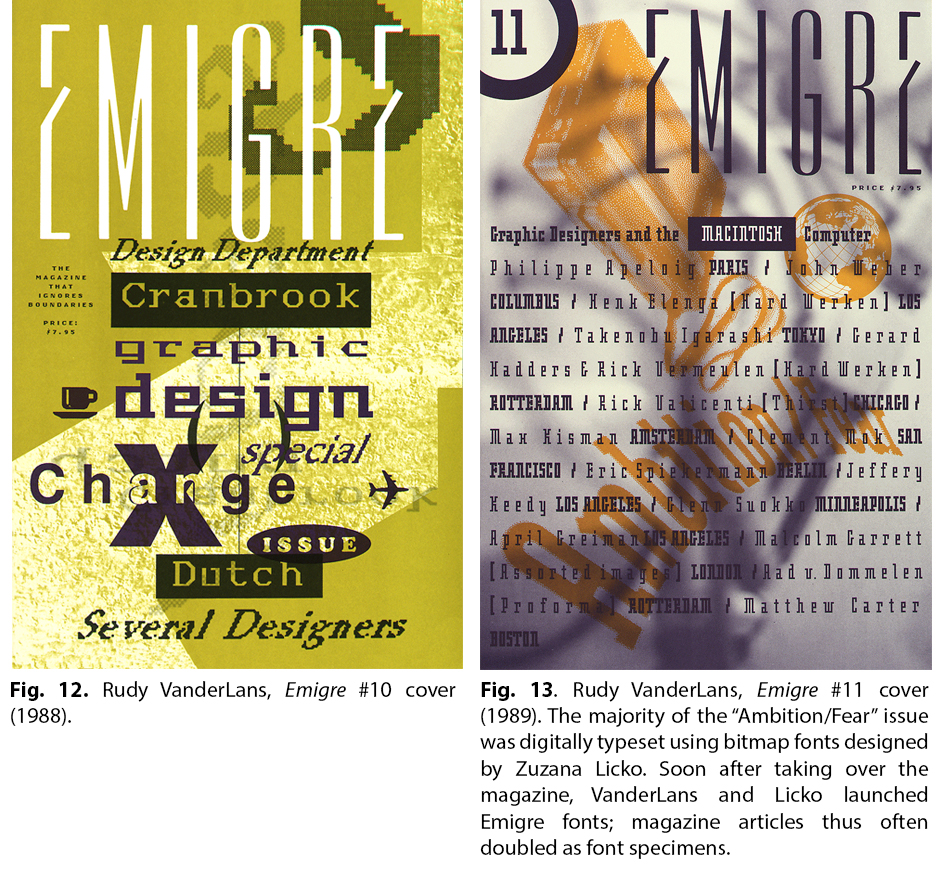

During the 1980s, postmodernists sought to overturn the one-size-fits-all functionalism into which modernist graphic design had settled. The coincidence of several economic, technical, and cultural forces consolidated the impact of their efforts. In 1983, Philip Meggs published the field's first in-depth history textbook, A History of Graphic Design. Still a central text in design education, Meggs's book established a trajectory of modernism that concluded in corporate America: a portrait of a professional establishment primed for youthful subversion.1 In 1984, Apple released the first Macintosh computer, which combined a "what-you-see-is-what-you-get" visual interface with some of the earliest consumer software for page layout and image manipulation. Experiments with these new tools were documented and debated in independent design magazines like Emigre, which was published out of Berkeley, CA beginning in 1984. Finally, throughout the mid-1980s, students in graduate design programs — most centrally at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in the Detroit, MI suburbs — were turning to literary and cultural theory in their search for new methods and forms. The stage was set for a broad transformation of design practice. These efforts, however, were only unevenly successful. The movement's theoretical ambitions lost steam as postmodern style was pressed into the service of commodity differentiation during the 1990s.

This essay begins by describing the historical emergence of the design professions, with a focus on their position in an intensifying division of labor. It goes on to offer a brief account of modernist design's dreams of industrial rationality, liberal neutrality, and reconciliation between art and commerce. I read these aims alongside transformations in the nature of industrial work during the same period, with particular attention to automation and deskilling. The essay's main intervention then comes into focus as I reinterpret the visual and critical production of the postmodernists across two disparate contexts: the "moment of theory" in the late-twentieth century humanities and the shifting landscape of post-Fordist work. In attempting to grasp and change their practice, postmodern designer-critics often stretched theoretical reflection to the point of obscuring the social relations in which that practice continued to be embedded — neglecting, in particular, the underlying violence of deindustrialization.

In examining the vexed relationship between theoretical self-reflexivity and social domination, this essay also contributes to recent efforts to trace the rise and recuperation of what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello term the "artistic critique" of capitalism.2 Graphic designers conceptualized postmodernism as a millennial liberation from constraint, routine, and hierarchy. In this they conflated modernist style with features of Fordist capitalism — a social form already in retreat by the 1980s. The postmodernist line of critique, as Boltanski and Chiapello have illustrated, in fact drew on much older traditions of resistance to capitalist work; graphic designers, however, were reluctant to conceptualize their practice in these terms. Meanwhile, print workers encountered the decline of Fordism in the form of deskilling, speedup, and the loss of shop-floor control. Those who were rendered superfluous to the new processes of print production were thus "freed" from their constrained and routinized labor — along with the wage that labor once secured. From either perspective, it was evident that the old certainties were disintegrating.

Modernism and the Rationalization of Work

As the design historian Adrian Forty has documented, the design professions were both a product of the capitalist division of labor and a factor in its further development.3 In key eighteenth-century crafts, the erosion of trade knowledge was accompanied by the rise of a new role in production: that of the "modeller."4 In Josiah Wedgwood's ceramic works, for example, these early designers acted as an intermediary between bourgeois taste and the labor process: new fashions were mediated by imperatives to simplify production into a rigid series of straightforward tasks. The contemporaneous vogue for restrained Neoclassicism provided an ideal opportunity to streamline production—with the express goal, in Wedgwood's words, of "mak[ing] such Machines of the Men as cannot err."5

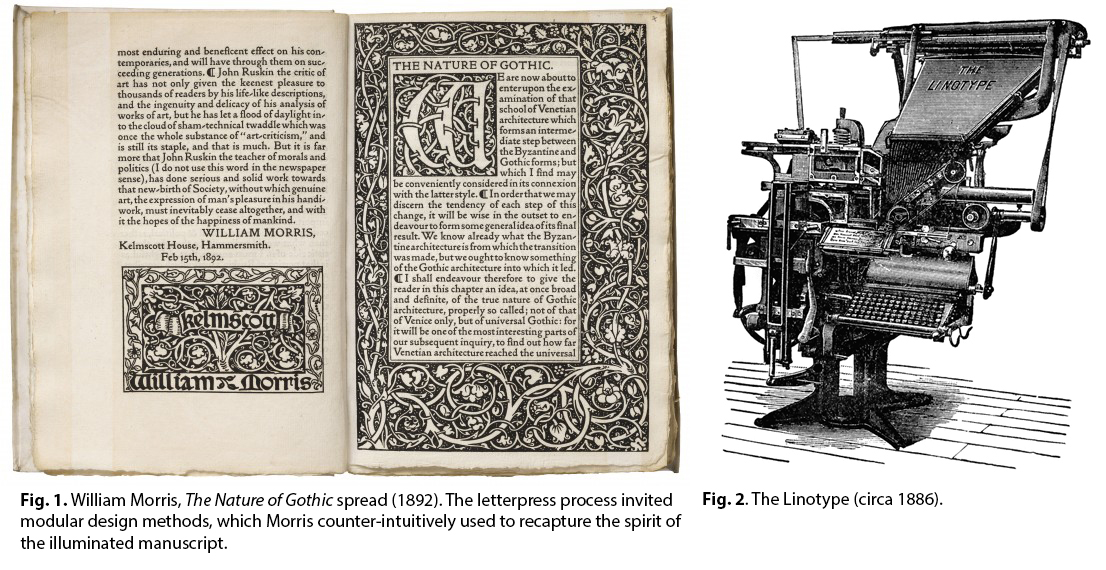

This managerial capture of trade knowledge — and the resultant degradation and cheapening of work — was noticed early on by Wedgwood's contemporary Adam Smith, who opened The Wealth of Nations with an account of similar changes in a pin factory. In contrast to the earliest factories, in which the entrepreneur simply gathered formerly-independent artisans to practice their trade side-by-side, here the pin-making process was exploded into a line along which each laborer only cuts, sharpens, or polishes.6 Smith notes the miraculous extension of productivity in a process thus rationalized; elsewhere, however, he laments that the "great body of the people" will increasingly fill their days repeating the same few tasks.7 Smith's fear that "the man whose whole life is spent performing a few simple operations ... has no occasion to exert his understanding" was also on John Ruskin's mind as he wrote what would become a central text of the Arts & Crafts movement's anti-industrial critique.8 In "The Nature of Gothic," Ruskin laments "the little piece of intelligence" rationed out to the factory worker, which "exhausts itself in making the point of a pin."9 For Ruskin, the division of labor is more accurately the division of the workers themselves into "mere fragments" of people; these abundant pins are polished with the "crumbs" and "dust" of human capacities.10 Originally a chapter of Ruskin's 1851-53 The Stones of Venice, "The Nature of Gothic" was republished by William Morris in 1892 via his Kelmscott Press (see fig. 1). Kelmscott employed skilled craftsmen at higher-than-average wages, aiming to restore care and aesthetic unity to the book printing tradition, which Morris felt had been undermined by industrial shoddiness. To his displeasure, however, this kept the prices of his books forbiddingly high.11

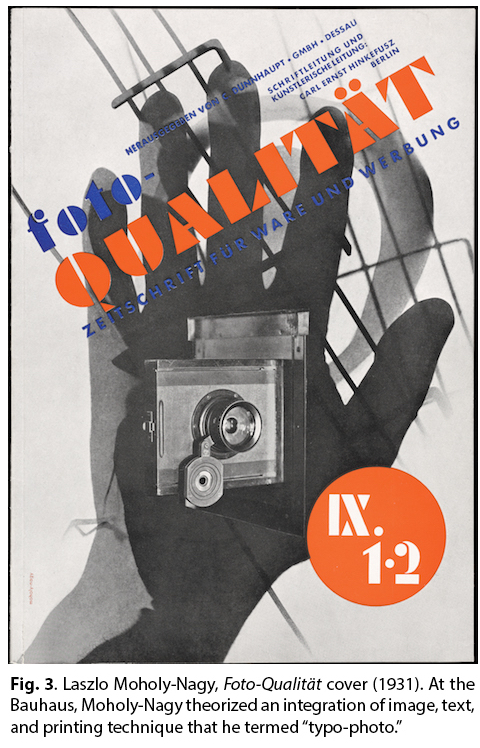

It would be up to a younger generation of practitioners in the United States to reconcile Morris's production standards with industrial printing. Under the influence of the Arts & Crafts movement, "commercial artists" like Frederic Goudy and his student W.A. Dwiggins reinvented themselves as freelance specialists in typography and printing.12 It was Dwiggins who first used the phrase "graphic design" to describe this emerging position in the division of labor.13 As the typographer and type historian Robin Kinross has documented, such early graphic designers redefined their own role while rationalizing the work of typesetters in their studios—in part by embracing technologies like the keyboard-driven Linotype, which replaced manual typesetting during the early twentieth century (see fig. 2).14

In 1901, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright broke ranks with Morris in an argument that upheld the printing press as the symbol of modernity's utopian horizon. In "The Art and Craft of the Machine," Wright argues that Morris's desired reconciliation between art, labor, and life was now most likely to be achieved by mechanization itself.15 While Morris's critique was valid for its time, Wright argues, the machine now appears in a new light: as "Intellect mastering the drudgery of the earth."16 If outmoded understandings of art are left to the past, workers and materials alike will be spared the "mass of meaningless torture" involved in crafting traditional ornament.17

In 1901, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright broke ranks with Morris in an argument that upheld the printing press as the symbol of modernity's utopian horizon. In "The Art and Craft of the Machine," Wright argues that Morris's desired reconciliation between art, labor, and life was now most likely to be achieved by mechanization itself.15 While Morris's critique was valid for its time, Wright argues, the machine now appears in a new light: as "Intellect mastering the drudgery of the earth."16 If outmoded understandings of art are left to the past, workers and materials alike will be spared the "mass of meaningless torture" involved in crafting traditional ornament.17

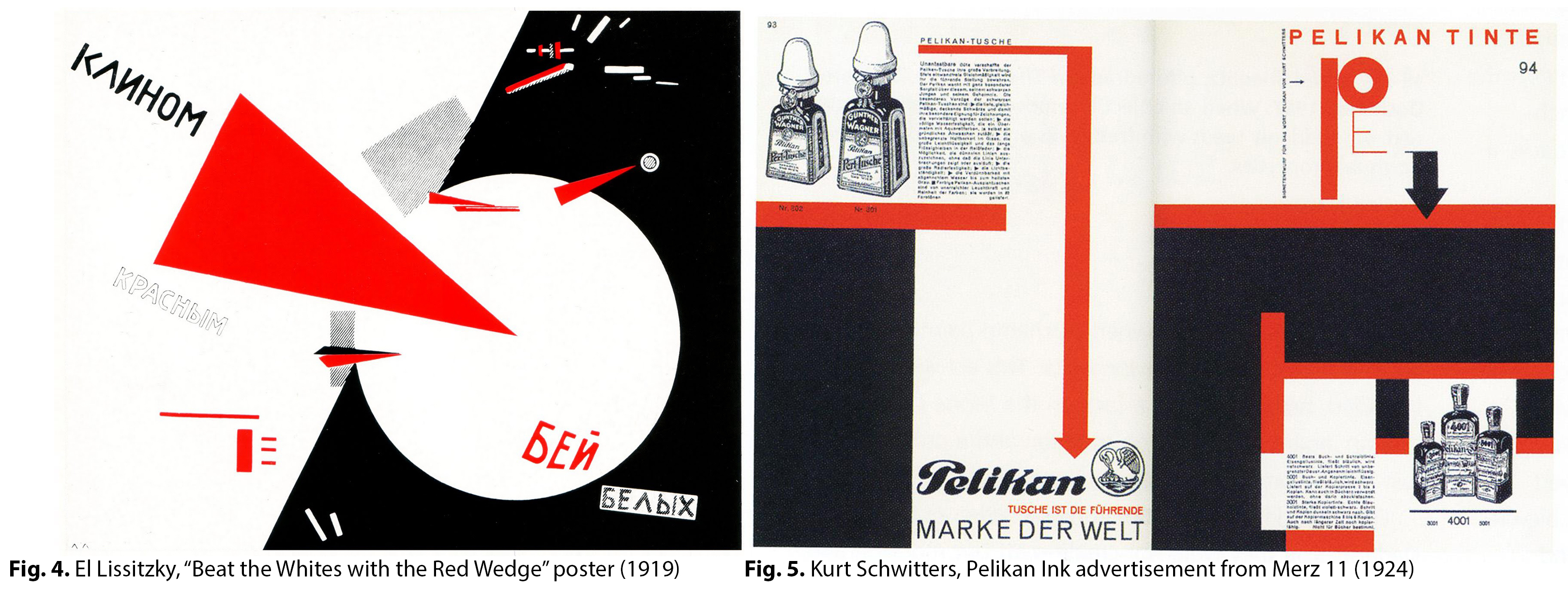

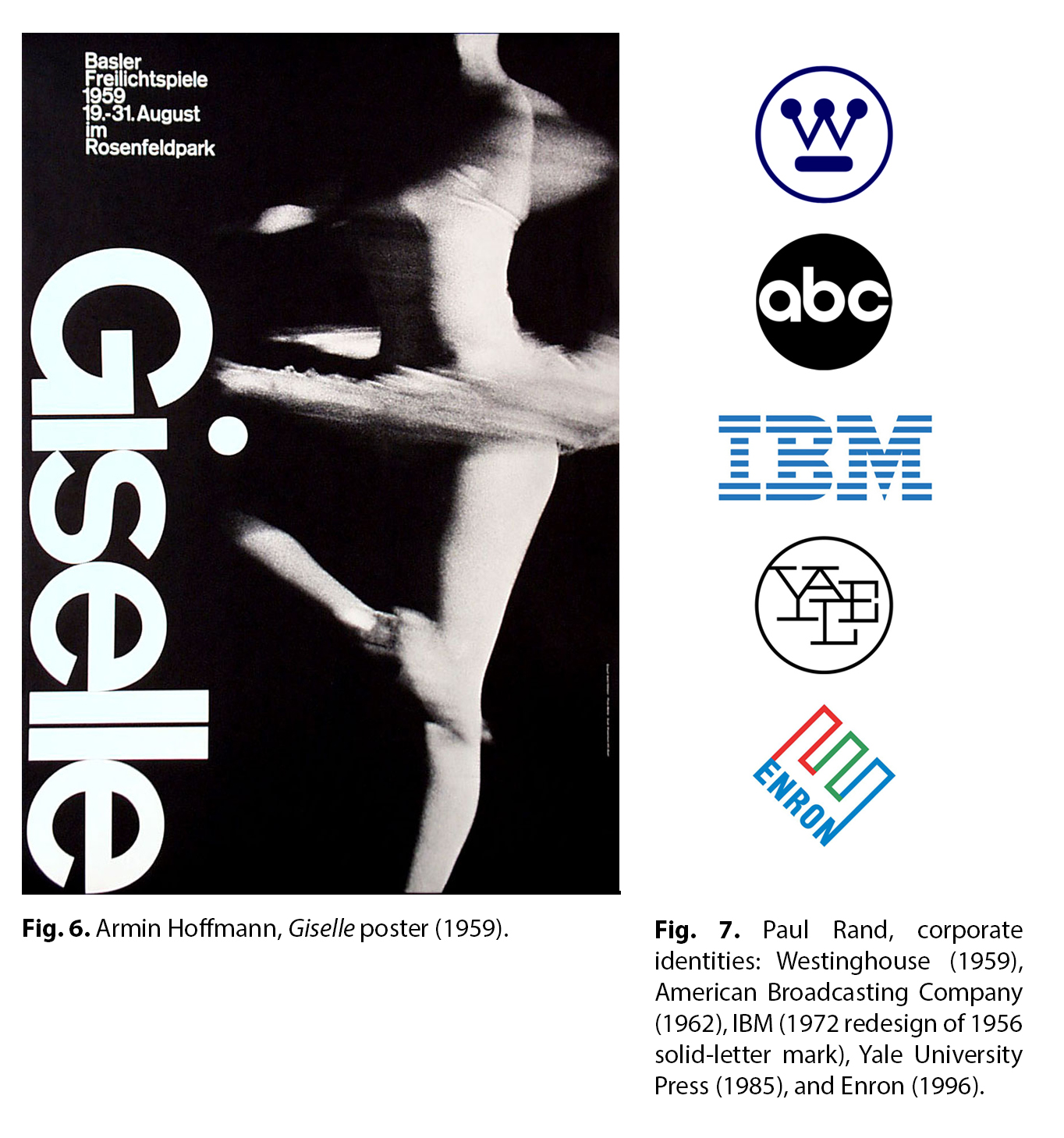

A similar perspective is evident throughout the early modernist movements. In their 1922 manifesto, the Constructivist Group promised war on traditional art and pledged a conditional allegiance to the machine: the Constructivists would be both technology's "first fighting and punitive force" and its "last slave-workers."18 The transformation of Bauhaus pedagogy between 1919 and 1933 also highlights the relationship between critical reflection on the division of labor and the development of the modernist "machine aesthetic." The school was initially organized along guild lines: composed of masters, journeymen, and apprentices rather than professors and students.19 In transitioning from a craft emphasis to industrial functionalism, graphic designers at the Bauhaus synthesized compositional lessons from Futurism, Dada, DeStijl, and Constructivism. Despite the important formal and political differences between these movements, all of them had undertaken some experimentation with the interface of photography and printing. The photochemical transfer of paper montage to printing plates allowed silence, noise, and chance juxtaposition to disrupt the rectilinear strictures of the letterpress (see fig. 3). For many avant-garde practitioners, such innovations presaged deep transformations of the human sensorium. Passing through photography, El Lissitzky argues in 1926, text and image become products of a common visual medium. Experimentation on the form of the book thus enables "the perpetual sharpening of the optic nerve."20 Citing the potentials of text-as-image, Lissitzky identifies a broad historical tendency toward dematerialization: "cumbersome masses of material," he predicts, will increasingly be "supplanted by released energies."21

As modernism was becoming codified at the Bauhaus during the 1920s, figures such as Lissitzky in the USSR, Theo van Doesburg in the Netherlands, and Kurt Schwitters and Jan Tschichold in Germany aided the international cross-pollination of new graphic approaches. Schwitters and Tschichold in particular worked to square these approaches with the contingencies of advertising and commercial printing (see figs. 4 and 5). Under mounting pressure from the Nazi Party, the Bauhaus closed in 1933; the same year, Tschichold was arrested for promoting "un-German" and "cultural Bolshevik" aesthetics.22 In part through forced emigration, the late interwar period saw an accelerated global dispersal of modernist design ideas. Despite its origins in a critical engagement with materials and labor, modernist style was meanwhile transforming into an apolitical symbol of industrial efficiency.

As modernism was becoming codified at the Bauhaus during the 1920s, figures such as Lissitzky in the USSR, Theo van Doesburg in the Netherlands, and Kurt Schwitters and Jan Tschichold in Germany aided the international cross-pollination of new graphic approaches. Schwitters and Tschichold in particular worked to square these approaches with the contingencies of advertising and commercial printing (see figs. 4 and 5). Under mounting pressure from the Nazi Party, the Bauhaus closed in 1933; the same year, Tschichold was arrested for promoting "un-German" and "cultural Bolshevik" aesthetics.22 In part through forced emigration, the late interwar period saw an accelerated global dispersal of modernist design ideas. Despite its origins in a critical engagement with materials and labor, modernist style was meanwhile transforming into an apolitical symbol of industrial efficiency.

In the postwar era, Switzerland became the center of the "International Style" in graphic design, characterized by sober sans-serifs and deadpan, usually colorless photographs (see fig. 6). This "objective" and "neutral" approach promised an alternative to the political propaganda recently seen in Europe and the overtly manipulative advertising emanating from the United States.23 In the US, on the other hand, modernism strove for universal objectivity and market dominance at once. In contrast to the Constructivists, who claimed to have abandoned art for engineering, corporate modernists saw themselves as artists whose "canvases" were large technocratic institutions. American corporations happily adopted their minimalist spatial organization, primary colors, and geometric typefaces (see fig. 7). A central figure here was Container Corporation of America (CCA) president Walter Paepke. CCA advertising campaigns of the 1940s and '50s eschewed overt sales messages in favor of abstract ideas presented in a modern visual idiom.24 Papke's International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was built on the idea that design was no longer simply a link to production; it now deserved its own role in management.25 Design, Paepke argued, could not only improve market competition between large firms tied to uniform machinery and wage agreements: designers could even be put to work on internal issues like worker morale.26

In the postwar era, Switzerland became the center of the "International Style" in graphic design, characterized by sober sans-serifs and deadpan, usually colorless photographs (see fig. 6). This "objective" and "neutral" approach promised an alternative to the political propaganda recently seen in Europe and the overtly manipulative advertising emanating from the United States.23 In the US, on the other hand, modernism strove for universal objectivity and market dominance at once. In contrast to the Constructivists, who claimed to have abandoned art for engineering, corporate modernists saw themselves as artists whose "canvases" were large technocratic institutions. American corporations happily adopted their minimalist spatial organization, primary colors, and geometric typefaces (see fig. 7). A central figure here was Container Corporation of America (CCA) president Walter Paepke. CCA advertising campaigns of the 1940s and '50s eschewed overt sales messages in favor of abstract ideas presented in a modern visual idiom.24 Papke's International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was built on the idea that design was no longer simply a link to production; it now deserved its own role in management.25 Design, Paepke argued, could not only improve market competition between large firms tied to uniform machinery and wage agreements: designers could even be put to work on internal issues like worker morale.26

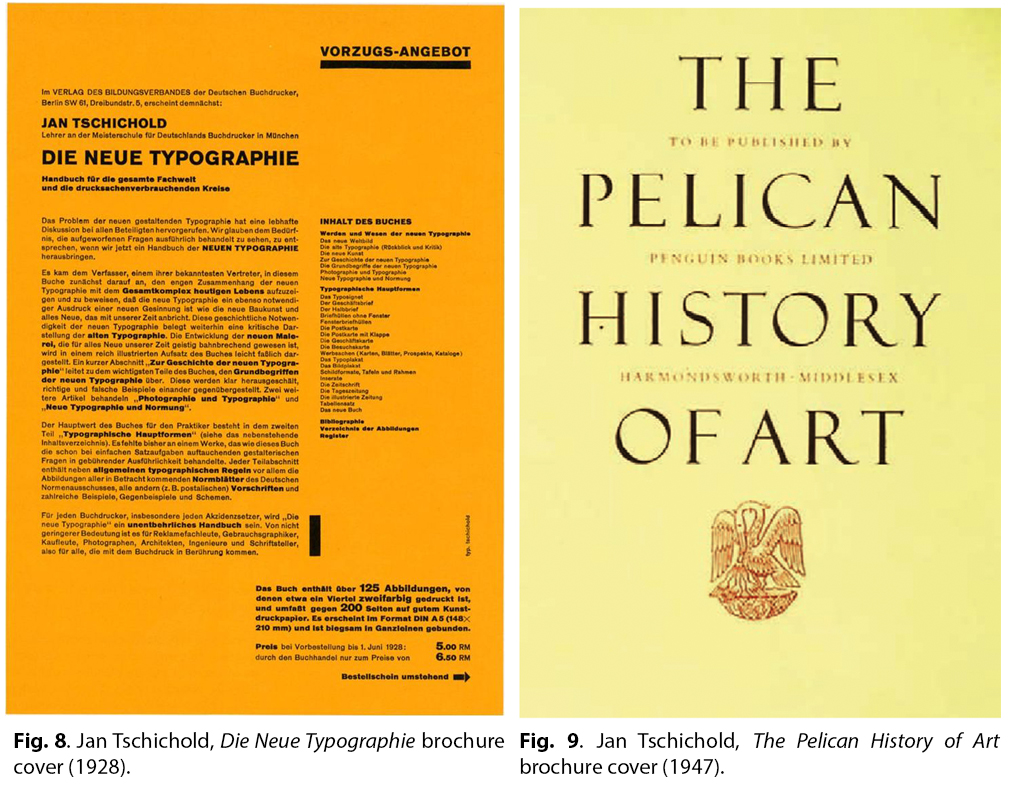

As print production grew more rationalized and further divided from the design process, the question of labor could thus appear as one of many "problems" to be "solved," rather than as an issue integral to the practice. In the postwar period, Tschichold became an unsparing critic of this increasingly technocratic and apolitical modernism. His writings had once gleefully endorsed the eradication of "degenerate typefaces and arrangements" by the spirit of standardized technology.27 Such a statement, needless to say, took on a changed significance in the aftermath of mechanized genocide and war. In response, he repudiated these positions and mostly abandoned the modernist New Typography he had pioneered; he also criticized his peers for continuing to innocently equate "the modern" with "the good" (see fig. 8 and 9).28 In a 1946 exchange with the Swiss designer Max Bill, Tschichold confronts modernism with the deep contradictions of modernity, which are clearly manifest in design production itself. Tschichold highlights the "heavy, almost deadly loss in the value of experience" of machine typesetters, whose stultifying labor amply illustrates the downside of modernist design's vaunted rationalism and restraint.29

As print production grew more rationalized and further divided from the design process, the question of labor could thus appear as one of many "problems" to be "solved," rather than as an issue integral to the practice. In the postwar period, Tschichold became an unsparing critic of this increasingly technocratic and apolitical modernism. His writings had once gleefully endorsed the eradication of "degenerate typefaces and arrangements" by the spirit of standardized technology.27 Such a statement, needless to say, took on a changed significance in the aftermath of mechanized genocide and war. In response, he repudiated these positions and mostly abandoned the modernist New Typography he had pioneered; he also criticized his peers for continuing to innocently equate "the modern" with "the good" (see fig. 8 and 9).28 In a 1946 exchange with the Swiss designer Max Bill, Tschichold confronts modernism with the deep contradictions of modernity, which are clearly manifest in design production itself. Tschichold highlights the "heavy, almost deadly loss in the value of experience" of machine typesetters, whose stultifying labor amply illustrates the downside of modernist design's vaunted rationalism and restraint.29

Modernists had imagined harnessing the technological dynamism of capital to extend and perfect human capacities — yet it increasingly appeared that machines did little more than objectify capitalist imperatives. The dialectic of dehumanization and freedom embodied in modern machinery was also a preoccupation of Marxist theorists from the interwar period through the middle of the century. Indeed, it was not uncommon for such writers to illustrate new problems of consciousness with reference to the work-processes involved in typography and design. In the 1930s, for instance, Antonio Gramsci's prison writings on Taylorism and Fordism take special notice of the intellectual and physical conditioning of Linotype operators. In order to draw out the potentials of routinized and rationalized work for forming new socialist subjects, he singles out machine typesetters' ability to dissociate from any "intellectual interest" in the texts on which they worked:30

Modernists had imagined harnessing the technological dynamism of capital to extend and perfect human capacities — yet it increasingly appeared that machines did little more than objectify capitalist imperatives. The dialectic of dehumanization and freedom embodied in modern machinery was also a preoccupation of Marxist theorists from the interwar period through the middle of the century. Indeed, it was not uncommon for such writers to illustrate new problems of consciousness with reference to the work-processes involved in typography and design. In the 1930s, for instance, Antonio Gramsci's prison writings on Taylorism and Fordism take special notice of the intellectual and physical conditioning of Linotype operators. In order to draw out the potentials of routinized and rationalized work for forming new socialist subjects, he singles out machine typesetters' ability to dissociate from any "intellectual interest" in the texts on which they worked:30

[T]he brain of the worker, far from being mummified, reaches a state of complete freedom. The only thing that is completely "mechanized" is the physical gesture; the memory of the trade, reduced to simple gestures repeated at an intense rhythm, nestles in the muscular and nervous centres and leaves the brain free and unencumbered for other occupations.31

In such a state of intellectual freedom, Gramsci argues, the worker's mind might even wander to revolution.32

Other Marxist theorists, however, shared Tschihold's concerns about the effects of highly alienated labor processes on the worker's ability to experience and to understand the social world. As Georg Lukács argues in 1923, alienation and reification are by no means limited to factory work; indeed, they seize the "creative" and "intellectual" heights of the division of labor with a particular intensity.33 Lukács argues that professionals encounter capitalism itself much as industrial workers encounter the assembly-line: as a mechanism whose rhythms are to be obeyed.34 Thus, while the professional's body may evade mechanization, his "conscientiousness" and "sense of responsibility" are drawn into the production process: the very interiority of the worker is thus put to work.35

In tracing the conflicts that attended what Lukács termed "Taylorism [in] the realm of ethics," the sociologist C. Wright Mills became particularly fascinated by the design industry.36 Writing in 1958 on the commercial artist's recent transformation into the modernist designer, Mills notes that the humble "Air Brush Boy" of the advertising office had suddenly become "the generalissimo of anxious obsolescence as the American way of life."37 Mills depicts the designer as a "man in the middle," caught in the gears of large, impersonal forces and frequently seized by "crippling frustration" and "guilt."38 The apparent authority of design's pact with management, he argues, is constantly undermined by the profit motive itself, which makes a mockery of aspirations to artistry and craftsmanship. For Mills, this was most clearly demonstrated in the phenomenon of planned obsolescence: a humiliation for designers who prided themselves on an ability to craft objective and durable solutions. As the architectural historian Wim de Wit has documented, these very complaints were voiced — albeit with more subtlety — among the "generalissimos" of corporate design at IDCA meetings during the mid-1950s.39

While designers worried over minor cyclical innovations in finish and form, genuinely disruptive inventions were taking hold of the typesetting industry. An "anxious obsolescence" of a different sort gripped print workers as the technical paradigm of the letterpress began to teeter during the mid-twentieth century. In the 1880s, the New York Tribune had funded research and development on the Linotype, which threw the hand-typesetting trade into turmoil by the turn of the century. The International Typographical Union (ITU), however, soon established jurisdiction over the machines, helping it to grow into one of the strongest unions in US history. This position, however, was soon threatened by further innovations: teletypesetting machines threatened to replace Linotype operators with punched tape, while photographic media were poised to supplant metal typography altogether.40 In 1964, the New York City local of the ITU signed a contract that allowed for teletypesetting and opened the door to similar agreements on phototypesetters and computers.41 The final night of Linotype composition at the New York Times is memorialized in the 1980 documentary Farewell Etaoin Shrdlu, directed by ITU member David Loeb Weiss.42 Among the film's interviewees is a compositor who reflects on his 26 years in the industry:

[T]hat's six years apprenticeship, 20 years journeyman. And these are words that aren't just tossed around ... All the knowledge I've acquired over these 26 years is all locked up in a little box now called a computer. And I think probably most jobs are gonna end up the same way.43

By the mid-1980s, new digital tools were completing typography's process of dematerialization. When the ITU dissolved in 1986 — amid a much broader neoliberal attack on organized labor — it had been the longest-running union in the United States. For Gramsci, the "mechanization" of the Linotype worker's gestures promised to free his mind; fifty years later, "the memory of the trade" would be unceremoniously "locked up in a little box."

As Weiss's compositor predicted, personal computers like the Apple Macintosh quickly centralized control over typography — from the spacing between letters and lines to the sequential organization of entire books. Such capacities had formerly relied upon massive metal-founding operations, delicate apparatuses of type on film and, finally, electronic systems built around wardrobe-sized computers. Each of these paradigms, in turn, connected numerous workers divided into distinct specializations and roles. The Macintosh would soon offer image-editing capacities with no existing analogue, which in turn put pressure on commercial photographers and illustrators. By the late 1980s, then, design responsibilities that had been contracted out with some combination of strict direction and trust were now fully under the control of the individual designer.

The convergences and displacements that had been predicted by Lissitzky thus reached their zenith with the digital hybridization of word processing, typesetting, and imaging. However, these transformations ultimately owed more to the bottom lines of print capitalists — particularly in the American newspaper industry — than to the utopian predictions of the radical modernists. What Lissitzky had termed the "released energies" of print's dematerialization now took the form of outmoded workers. The consummation of industrial modernization would, meanwhile, have unexpected ramifications for modernist design. Labor-saving innovations in typesetting technology would contribute to a loosening of modernism's grip on the graphic design profession.

Postmodernism: From Style to Theory

Critiques of modernity were being articulated within the design disciplines as early as the 1960s. The placid neutrality of modernist design was felt to be in intensifying conflict with a world beset by various crises. At the IDCA's 1970 "Environment by Design" meeting, for instance, a group of Berkeley students descended on Aspen and nearly derailed the conference for good. The group staged ecologically-themed happenings and forced a vote on resolutions to end the Vietnam War and "the persecution of Blacks, Mexican-Americans, women, and homosexuals," as well as demanding fundamental transformations of the national economy.44 Graphic designer Saul Bass — best known for his corporate identities and Hollywood title sequences — spoke for the IDCA board when he asked the students, "Why do we have to assess capitalism? We're just trying to stage a conference!"45

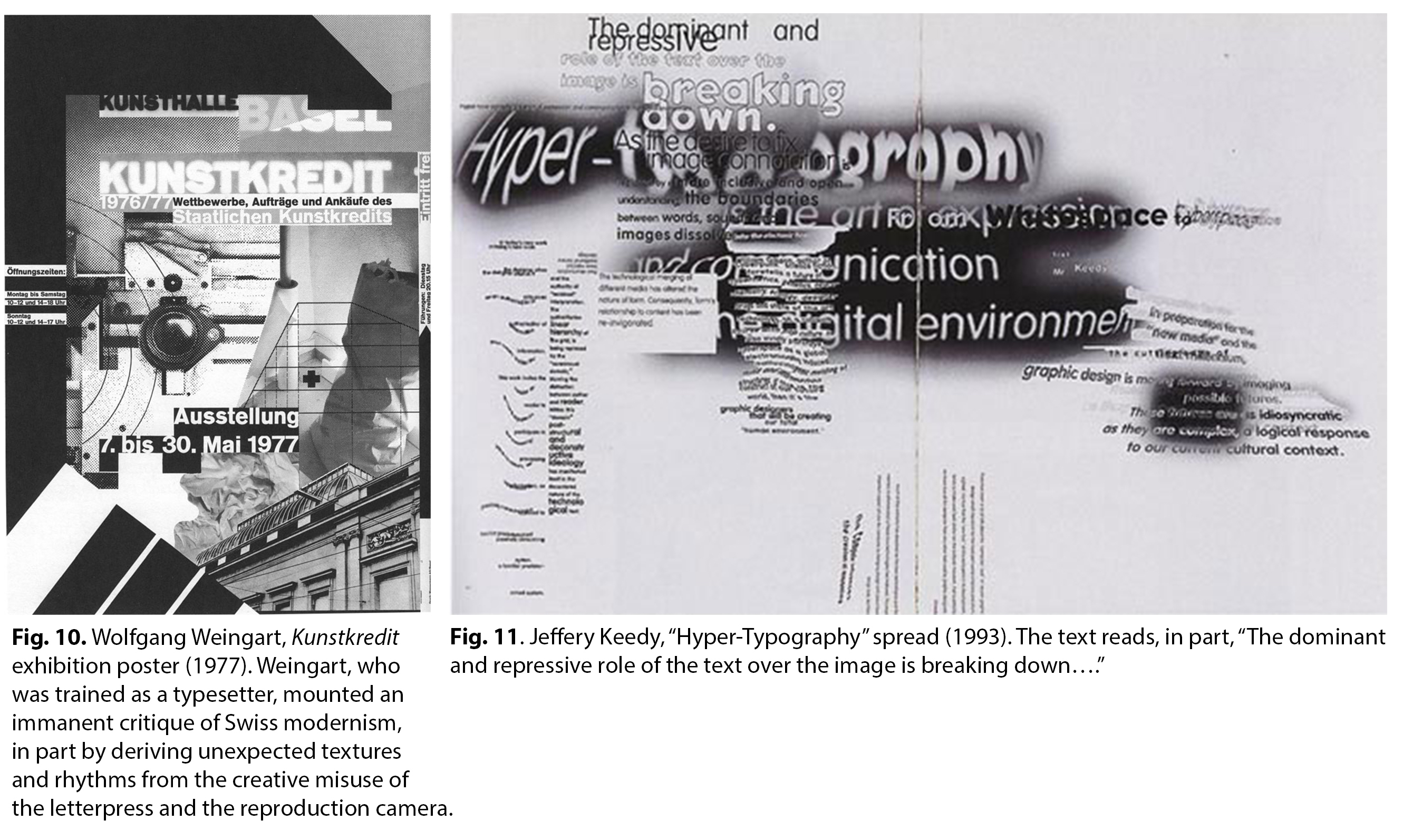

In graphic design, by contrast, the generational polemics of the next decades would largely remain within the bounds of professional practice. The social relations in which the profession was embedded were less of an issue than the limited repertoire of the modernist establishment. The 1960s had seen the first signs of modernism's critique; Pop Art, psychedelia, and countercultural publishing nurtured a new graphic sensibility among a younger generation of practitioners. Technical developments, in turn, opened aesthetic possibilities of their own. Corporate modernism's reign had overlapped with the rise of phototypesetting, which streamlined the production of clear grids and sharp contrasts. The same technologies, however, made it possible to overlap and to distort — and the Macintosh rendered such operations increasingly simple and intuitive (see figs 10 and 11). Thoroughly automated and rationalized design tools thus facilitated the subversion of long-standing visual conventions. The same modernization process that had rendered typesetting obsolete lent graphic design a new sense of autonomy that, in turn, fueled new challenges to its professional establishment.46

Postmodernists sought out intellectual justification for these new forms and methods, and they increasingly found it in "theory": specifically, in contemporaneous writing on the postmodern condition and in the "cultural" and "linguistic" turns in the humanities. By the late 1980s, the critique of modernist principles had intensified under the flag of "deconstruction." Experimenting with new digital tools, designers retread and intensified the avant-garde's experiments in structure: balanced grids of text became assaults of competing figures, syllables, and phrases.47 Such interventions, in turn, inspired a wave of self-reflexive writing by designers. Deconstructionist innovations were theorized as attempts to undermine Eurocentric narratives in design history; to kill off "the Author" and restore contingency and indeterminacy to the experience of reading; or simply to enrich staid commercial messaging with messy, unpredictable affects.

Postmodernists sought out intellectual justification for these new forms and methods, and they increasingly found it in "theory": specifically, in contemporaneous writing on the postmodern condition and in the "cultural" and "linguistic" turns in the humanities. By the late 1980s, the critique of modernist principles had intensified under the flag of "deconstruction." Experimenting with new digital tools, designers retread and intensified the avant-garde's experiments in structure: balanced grids of text became assaults of competing figures, syllables, and phrases.47 Such interventions, in turn, inspired a wave of self-reflexive writing by designers. Deconstructionist innovations were theorized as attempts to undermine Eurocentric narratives in design history; to kill off "the Author" and restore contingency and indeterminacy to the experience of reading; or simply to enrich staid commercial messaging with messy, unpredictable affects.

Here I concentrate on key aspects of postmodernism as it took shape around two small American institutions: Emigre magazine in Berkeley, California and the graduate program in "2D Design" at Cranbrook Academy in the Detroit, Michigan suburbs. Both were early adopters of the Macintosh computer, and both became hotbeds of theoretical debate. Launched in 1984, Emigre was initially an artist publication loosely arranged around the experience of cultural hybridity.48 Dutch designer Rudy VanderLans took over as the magazine's publisher in 1986; thereafter, an increasing use of digital typesetting coincided with a gradual shift to graphic design as content — a move cemented by a special issue on Cranbrook in 1988 and another on the Macintosh in 1989 (see figs. 12 and 13).

In the mid-1980s, Cranbrook participated in a pilot program for integrating personal computers into design education.49 During the same period, recalls then-director Katherine McCoy, Cranbrook studios had come to resemble a "theory-of-the-week club":

In the mid-1980s, Cranbrook participated in a pilot program for integrating personal computers into design education.49 During the same period, recalls then-director Katherine McCoy, Cranbrook studios had come to resemble a "theory-of-the-week club":

[S]tructuralism, post-structuralism, deconstruction, phenomenology, critical theory, reception theory, hermeneutics, lettrism, Venturi vernacularism, post-modern art theory ... gradually the ideas were sifted through, assimilated, and the most applicable began to emerge.50

By the end of the 1980s, the confluence of theory and personal computers had produced a recognizable agenda at Cranbrook (see fig. 14). In 1990 McCoy described the methods of what she termed the new "American design expression," which "demands effort of the audience, but also rewards the audience with content and participation."51 Evoking "deconstruction's contention that meaning is inherently unstable and that objectivity is an impossibility," McCoy argues that these new design approaches no longer seek to "control the audience" with a singular message — rather, they open space for "individual interpretations" that "'decenter' the message."52

In McCoy's interpretation of the author-function and reader response, Roland Barthes's "birth of the reader" requires specialist guidance: the designer constructs the very possibility of epistemic instability and play. The anti-hierarchical demand of participation becomes a "reward" that the deconstructionist designer bestows in exchange for the reader's "work." Practitioner-critics like McCoy wrote themselves into theory in imaginative ways, but their anti-authoritarian promises often sat uncomfortably with an evident desire to augment graphic design's intellectual and professional standing. McCoy envisioned designers increasingly taking on "roles associated with both art and literature"53 even as they ascended into a "higher level in the business hierarchy."54 Depicting the designer as someone with the power to hold readers prisoner — or to set them free — reflected the confidence of the profession after Meggs and the Macintosh. A newly consolidated understanding of historical precedents and a tightening grip on the production process lent graphic design a new sense of coherence and power. Theoretical analyses of power relations would thus largely be confined to the interpretive authority or openness that a given graphic approach ostensibly provided. The conditions of unfreedom in which most designers still worked — such as those highlighted by Mills thirty-five years earlier — received far less attention.

In McCoy's interpretation of the author-function and reader response, Roland Barthes's "birth of the reader" requires specialist guidance: the designer constructs the very possibility of epistemic instability and play. The anti-hierarchical demand of participation becomes a "reward" that the deconstructionist designer bestows in exchange for the reader's "work." Practitioner-critics like McCoy wrote themselves into theory in imaginative ways, but their anti-authoritarian promises often sat uncomfortably with an evident desire to augment graphic design's intellectual and professional standing. McCoy envisioned designers increasingly taking on "roles associated with both art and literature"53 even as they ascended into a "higher level in the business hierarchy."54 Depicting the designer as someone with the power to hold readers prisoner — or to set them free — reflected the confidence of the profession after Meggs and the Macintosh. A newly consolidated understanding of historical precedents and a tightening grip on the production process lent graphic design a new sense of coherence and power. Theoretical analyses of power relations would thus largely be confined to the interpretive authority or openness that a given graphic approach ostensibly provided. The conditions of unfreedom in which most designers still worked — such as those highlighted by Mills thirty-five years earlier — received far less attention.

In 1993, Steven Heller published his terse critique "Cult of the Ugly," a broad attack on deconstruction provoked by Cranbrook designers in particular.55 Heller, who was by then a prolific design journalist, had gotten his start in underground newspapers like Screw in the late 1960s. Noting the element of "critical ugliness" in Futurism, Dada, and the '60s counterculture, Heller argues that the deconstructionists seem comparatively isolated from any broader social "upheaval."56 While Heller is skeptical of the new theories animating deconstructionist design, he cautions that the style will inevitably circulate independently of its intent; a nihilistic arms race of "ugliness" might then begin to undermine the hard-won continuity of the profession.57

Partly in response to the criticism of figures like Heller, theoretical arguments began to appear with increasing frequency in magazines like Emigre.58 Cranbrook alumnus Andrew Blauvelt — best known for his more recent design and curatorial work at the Walker Art Center — repeatedly enlisted cultural theory in these battles.59 In a 1994 essay, Blauvelt criticizes Heller's "politics of tastemaking," which amounts to little more than a "defense of conventional (mainstream) professional practice with clearly definable limits."60 Blauvelt calls attention to Heller's use of value-laden descriptive terms: "harmony" and "beauty," for example, are arrayed against "chaos" and "ugliness" without further elaboration.61 Whereas Heller described the graduate-school work as "driven by instinct and obscured by theory,"62 Blauvelt shifts the focus to the unexamined "theory" on which the profession stands. Critiques like Heller's, he argues, depend on a 'set of theories about how graphic design is allowed to exist in society,' which naturalize arbitrary rules of professionalism.63 He concludes:

Ironically, the keys to understanding this condition are to be found in the realm of the theoretical—a space where a critical, reflexive approach can expose these rules not as given or "natural," but rather as constructed and alterable.64

The American design establishment was ill-equipped to respond to Blauvelt's theoretically-informed critique of professionalization. However, a fitting (if indirect) reply appeared the same year, when Robin Kinross published the pamphlet "Fellow Readers." 65 Though Kinross's pamphlet takes its name from Benedict Anderson's account of the role of print capitalism in the rise of national consciousness, its approach is best described as Habermasian.66 The political stakes of typography, for Kinross, arise from its role in an incomplete Enlightenment: "the long haul ... of secularization, of social emancipation."67 Kinross understands typography as unique among the crafts for its capacity to demystify its own tools and methods; the continuation of this Enlightenment role would include the publication of typographical criticism (like his own) in mainstream newspapers.68 Kinross contrasts this public-minded ideal to a satirical précis of deconstruction's "mish-mash of the obvious and the absurd,"69Adopting a voice that resembles McCoy's, he intones:

We know the world only through the medium of language. Meaning is arbitrary: without "natural" foundation. Meaning is unstable and has to be made by the reader. Each reader will read differently. To impose a single text on readers is authoritarian and oppressive. Designers should make texts visually ambiguous and difficult to fathom, as a way to respect the rights of readers.70

Kinross traces the problem to a motivated misreading of semiotic theory. Ferdinand de Saussure's insight into the arbitrary link between sign and signifier, Kinross argues, has been generously interpreted to mean that a solitary designer can "arbitrarily" intervene in the operation of signs already "established in a linguistic community."71 In its attempt to "act out the indeterminacy of reading," Kinross argues, deconstructionist design often enacts the very authoritarianism it ascribes to modernist practice.72 The visual "muddle" of the deconstructed page backhandedly imposes new contrasts and hierarchies: "Far from giving freedom of interpretation to the reader," he argues, deconstruction in fact "imposes the designer's reading of the text onto the rest of us."73

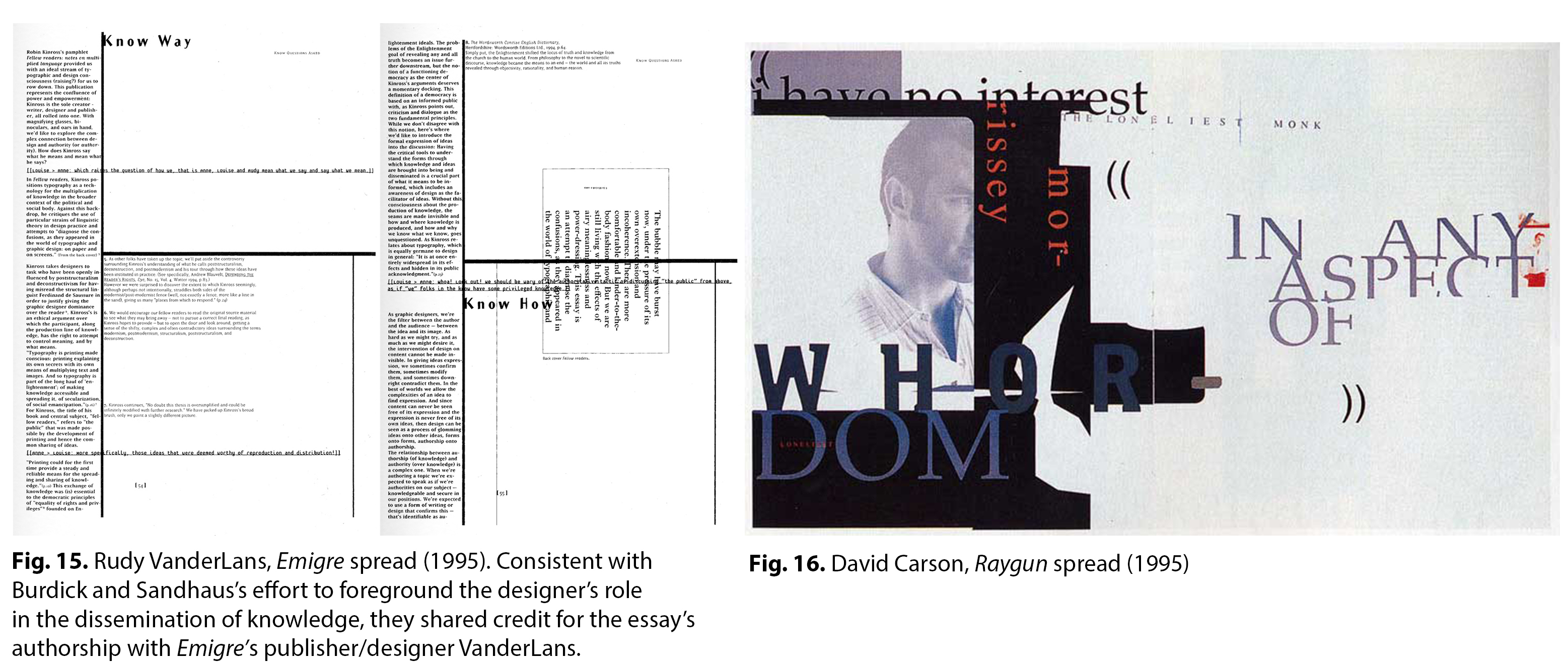

In 1995, design educators Anne Burdick and Louise Sandhaus published a review of Kinross's essay in Emigre.74 Their critique of Kinross quickly expands into a critique of modernist typographical conventions as a whole. In calling for an expanded "awareness of design" as a "facilitator of ideas," Burdick and Sandhaus are close to Kinross's own vision of typographical form as a subject of civic debate.75 In interrogating the visual mechanisms that fuse knowledge to power, however, they could be said to play Foucault to Kinross's Habermas. Where the latter treats typography as a neutral "technology for the multiplication of knowledge," Burdick and Sandhaus insist on typographical practices that foreground the designer's presence.76 A "disruptive" typography that "refus[es] to recede into the background," they argue, promises to expose "the designer's role in shaping what constitutes knowledge."77 Accordingly, the layout of "Know Questions Asked" becomes a literal representation of its argument; their critique confines itself to the margins, abandoning the remainder of the page to citations and to scans of Kinross's pamphlet — voices of "centered" authority (see fig. 15).78

Further complicating the layout, snippets of the authors' informal email correspondence straddle the boundary. It is here that Burdick relates the story of Felix Janssens, a designer who had stumbled onto a corrupt relationship between the Dutch political establishment and the large national newspaper that employed him as a designer. "If Felix were to publish an essay" about what he had learned, Burdick notes, "he might compromise his position as a professional dependent upon the authorities that be for his livelihood."79 Thus compromised, she reports, Janssens tried to make his discovery evident "through the selection and juxtaposition of certain photographs"; the effect, however, was "incredibly subtle" even to a reader looking for it.80 "Through our jobs," Burdick concludes, "graphic designers get to peek and poke around the insides of authority."81 But the limits on a designer's ability to act on what they may discover there are not further addressed.

Kinross's essay celebrates design practice insofar as it mediates a universal history of ideas; he thus instructs designers to "keep their heads down" and know their place as the arc of history makes its slow progress through the printed word.82 Burdick and Sandhaus, on the contrary, approach design's social role with critical suspicion: the knowledge that designers mediate is saturated with exclusion and deception. Yet when the elusive figure of "authority" briefly materializes in the person of an employer, their analysis abruptly breaks off. In both essays, then, a broad scope of social action is claimed — only to be quickly restricted to what the designer does on billable time. Despite their disagreements, both essays unwittingly highlight social constraints beyond the reach of designers qua designers.

It was Blauvelt, in a series of essays for Emigre, who most convincingly addressed the existence of abstract determinations beyond the reach of individual practice. Rather than citing theory to legitimate designers' self-expression, he used it to identify impersonal mediations and barriers. In 1994 and 1995, he published a two-part essay entitled "In and Around: Cultures of Design and the Design of Cultures."83 Here Blauvelt starkly de-emphasizes individual designers' agency, concentrating instead on the social structures that precede practice. Graphic designers are presented as mere moments in a potentially endless circuit of signification among semiotic communities. It is only in circulation, he argues, that cultural codes are given meaning.

This concept of a broad context of circulation, in which designers hold no privileged position, reappears in an essay Blauvelt published the following year. In "Desperately Seeking David, or, Reading Ray Gun, Obliquely," he questions the persistence of claims to personal expression in postmodern discourse.84 Graphic designers may have celebrated the death of the author, he suggests, because they had their eye on the "power vacuum" left in "his" place.85 The essay centers on a critique of the self-taught design auteur David Carson, whose music and youth-culture magazines popularized deconstruction as style, if not as theory (see fig. 16). The specificity of this target, however, creates problems for Blauvelt's argument. On one hand, he accuses Carson of stealing design ideas that originated in places like Cranbrook and Emigre. On the other, he argues that the context of circulation makes originality impossible; designers must instead learn to accept "repetition with a difference."86 Imputing the frustrations of aesthetic invention to a social condition in which designers and their audiences alike are forced to differentiate between "nearly identical products,"87 Blauvelt concludes the essay by massively expanding its stakes:

This concept of a broad context of circulation, in which designers hold no privileged position, reappears in an essay Blauvelt published the following year. In "Desperately Seeking David, or, Reading Ray Gun, Obliquely," he questions the persistence of claims to personal expression in postmodern discourse.84 Graphic designers may have celebrated the death of the author, he suggests, because they had their eye on the "power vacuum" left in "his" place.85 The essay centers on a critique of the self-taught design auteur David Carson, whose music and youth-culture magazines popularized deconstruction as style, if not as theory (see fig. 16). The specificity of this target, however, creates problems for Blauvelt's argument. On one hand, he accuses Carson of stealing design ideas that originated in places like Cranbrook and Emigre. On the other, he argues that the context of circulation makes originality impossible; designers must instead learn to accept "repetition with a difference."86 Imputing the frustrations of aesthetic invention to a social condition in which designers and their audiences alike are forced to differentiate between "nearly identical products,"87 Blauvelt concludes the essay by massively expanding its stakes:

The sign of these times conforms to the logic of a system in which the representation is more important than the actual thing. It is a time characterized by this splitting of the sign and its referent. It's about the multiplicity of meanings generated not only by designers but also actively constructed by readers. It's about the inability to close down interpretation. It's the kind of fuzzy logic that allows virtually anything to sell basically everything.88

In these breathless final lines, the antagonist no longer seems to be Carson himself, but rather a "time," a "system," or a "logic" that are either perennial conditions of semiosis or historically-specific symptoms of capitalism.

Read sympathetically, the overlapping shortcomings of each of these essays suggest a path not taken: one that would have allowed for the mediation of practice by the real abstractions of capital. Such an approach would have gone beyond a narrow critique of modernism's visual habits to explain how individual practice can become constrained by social forces which are, in turn, sustained by constrained forms of practice.89 Like language, capital is a social abstraction beyond the reach of individual intervention. A critical approach that began from the specificity of capitalism would have thus been able to explain why historical progress could, for Kinross, be plausibly depicted as an abstract process of the intellect. Such an approach could also have sustained and deepened Burdick and Sandhaus's suspicions of the power relations embedded in everyday work. It might even have nudged Blauvelt's insights about the constructedness and alterability of the social world out of the misty "realm of the theoretical," returning critical attention to the constrained spaces of the studio and the marketplace. Finally, an approach that situated design practice in the history of capitalism could have steered between the ostensibly timeless categories of semiotics and the biographical contingency that often limits the field's historiography.

It is, of course, no great mystery that graphic designers in search of intellectual inspiration did not opt to tackle the most forbidding aspects of Marx's critique of political economy — particularly during a decade of widespread "End of History" triumphalism. If such an approach was unlikely to appear practicable in the dominant intellectual atmosphere of the American humanities in the 1990s, it seems that this was twice as unlikely in an institution like Cranbrook, where the "freedom of the reader" appears to have taken preference over clarity on the politics of theory. In a 1991 interview, Katherine McCoy argued that "the Marxist element in literary theory" could simply be discarded for something more culturally appropriate to "upper middle-class graduate students in the Midwest." Literary theory could still be appreciated for its "anti-authoritarian" ideas, McCoy argued; however, these ideas could easily "bend" to suit "an American popular ethic, or better yet, a frontier individualist ethic, as opposed to the European late Marxist ethic."90

Burdick, Sandhaus, Kinross, and McCoy's reluctance to adopt a "Marxist ethic" — or even to make explicit their critique of a world in which the designer was "dependent upon the authorities that be for his livelihood" — should also be understood in the context of what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello have influentially named "the new spirit of capitalism."91 Boltanski and Chiapello identify a longstanding "artistic" critique of work, often emerging out of bohemian milieux and emphasizing the need for individual creativity and autonomy. As Jasper Bernes argues in The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization, this critique intensified in the 1960s via art and poetry: aesthetic practices gave form to anti-hierarchical demands like "participation," and artists and poets articulated radical critiques of work and its organization.92 Yet as Boltanski, Chiapello, and Bernes all go on to argue, as it gained strength this "artistic" critique ultimately supplanted and suppressed the "social" critique of work once seen in the classical labor movement, which had emphasized the collective struggle for security and dignity. By the 1980s and '90s, Boltanski and Chiapello observe, management theorists were advocating the incorporation of postmodern values — including self-expression and "flexibility" — into corporate structures that, on the other hand, increasingly refused to provide the job security that unions and long-term contracts had once promised.93

Much as new forms of readerly freedom and self-expression ultimately proved consistent, for McCoy, with the unthreatening image of "frontier individualism," artistic strategies of participation ultimately provided "key terms and coordinates" for what would become the dominant ideology of the post-Fordist workplace.94 Exhibiting traits of poets and business strategists at once, postmodern graphic designers were thus exemplary subjects of this new world of work. By the 1990s, it had become possible for a relatively privileged group of professionals to enlist the artistic critique in an interrogation of the realities of their work — and yet to do so with scarcely a mention of that work's capitalist context.

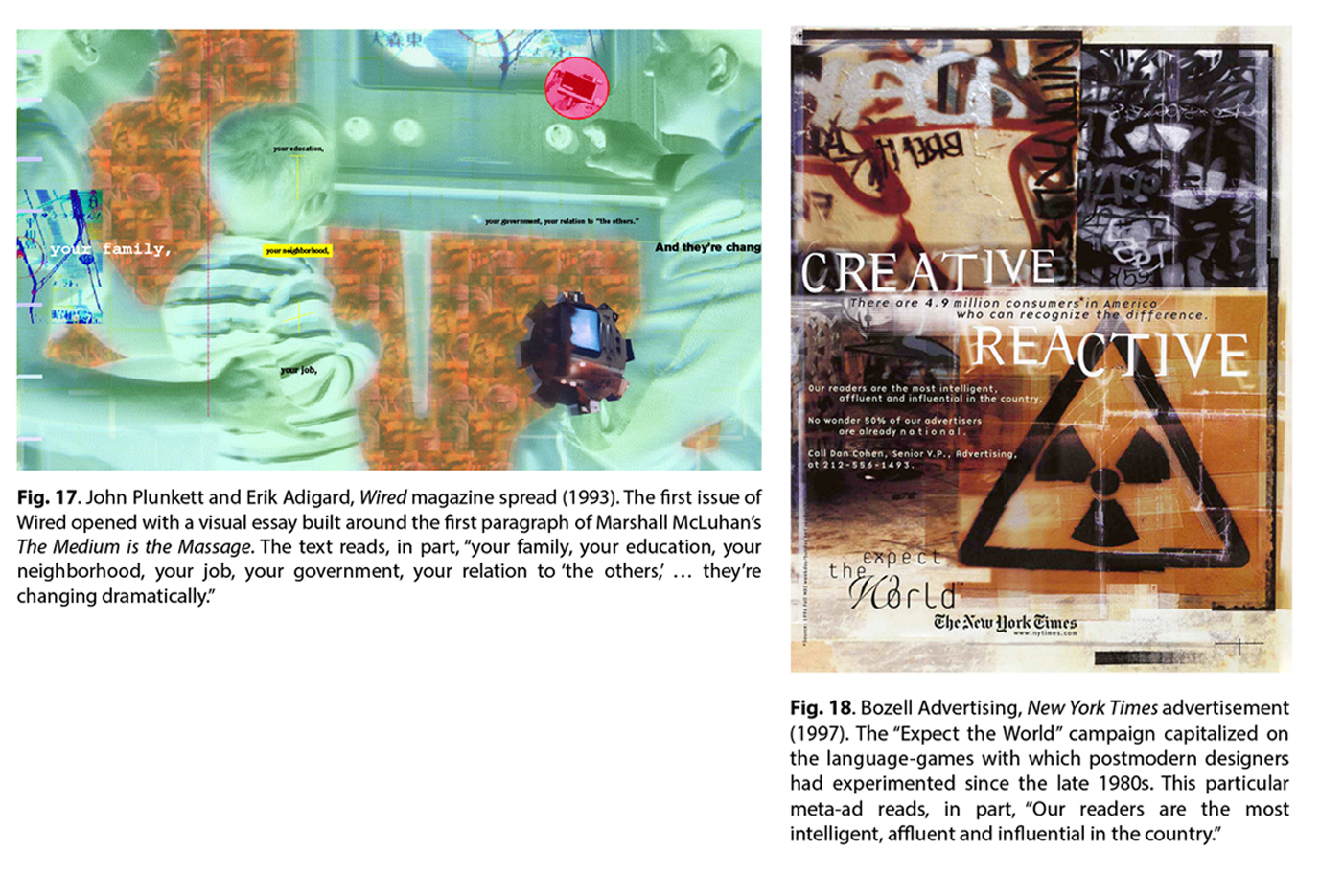

The postmodernist attack on the image of a rigidified and one-dimensional society crucial to the period of modernization echoed the supersession of Fordist capitalism already in progress. In the 1990s, a more fluid, volatile, and unpredictable form of capital-determined society thus found apt expression in the very surfaces of commercial exchange. As Blauvelt later observed in retrospect, it was "no coincidence that the proliferation of design styles corresponded with the increase of the number of brands and the demand for product segmentation."95 At the same time, the postmodern discourse evinced a lingering modernist optimism about emerging technologies, and a corresponding faith that an art wedded to such technologies could intervene directly in social consciousness. Despite their well-rehearsed criticisms of "grand narratives," postmodern designers often presented new digital tools as integral to a progressive historical overcoming of hierarchy and structure. A theoretical gestalt that suggested multiplicity and polysemy seemed confirmed by technological developments that promised new modes of expression and reduced barriers to entry. Such visions would turn out to be very compatible with libertarian exuberance that greeted the Internet and its attendant "New Economy" around the same time (see fig. 17).

The postmodernist attack on the image of a rigidified and one-dimensional society crucial to the period of modernization echoed the supersession of Fordist capitalism already in progress. In the 1990s, a more fluid, volatile, and unpredictable form of capital-determined society thus found apt expression in the very surfaces of commercial exchange. As Blauvelt later observed in retrospect, it was "no coincidence that the proliferation of design styles corresponded with the increase of the number of brands and the demand for product segmentation."95 At the same time, the postmodern discourse evinced a lingering modernist optimism about emerging technologies, and a corresponding faith that an art wedded to such technologies could intervene directly in social consciousness. Despite their well-rehearsed criticisms of "grand narratives," postmodern designers often presented new digital tools as integral to a progressive historical overcoming of hierarchy and structure. A theoretical gestalt that suggested multiplicity and polysemy seemed confirmed by technological developments that promised new modes of expression and reduced barriers to entry. Such visions would turn out to be very compatible with libertarian exuberance that greeted the Internet and its attendant "New Economy" around the same time (see fig. 17).

Looking for work

In the writings of postmodernist graphic designers, early socialist demands for meaningful, unalienated work often seem to resurface; such demands, however, usually reappear welded to capitalist practice. Writing in 1990, Emigre publisher Rudy VanderLans aptly captured this contradictory sense of possibility:

In a sense, everything can be learned on the job, even critical thinking, exploration, introspection, offset printing, intellectual development, bookkeeping, French literary criticism, programming, [and] contract writing ... It can all be learned as you slowly develop into the all-around professional you're supposed to be.96

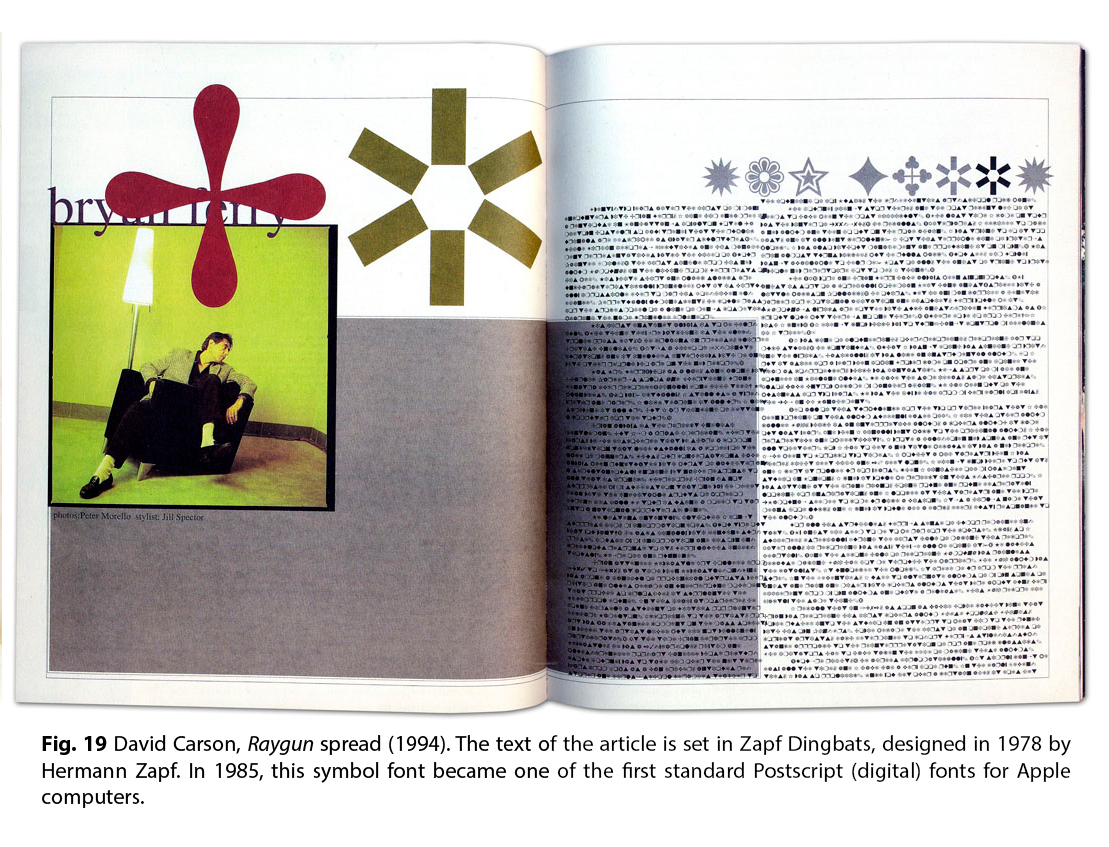

For the optimistic, the job was identified as a site of nearly limitless human potential. However, the day-to-day demands of working life caught up with many of the short-lived movement's practitioner-theorists. As VanderLans admits in Emigre's final issue in 2005, his activities as a designer and publisher had left him little time or patience for theory. Robert Venturi's accessible writing on vernacular architecture, he notes, "spurs me to finally read Barthes and Derrida and some of the others. After several tries, I realize I'm ill prepared for the philosophical complexity. I cannot bear to read through them."97 VanderLans concludes with a rumor from Cranbrook that he was relieved to hear: the graduate students, already feeling stifled by theory, were now reading Charles Bukowski instead.98 As the energy behind the foray into theory began to ebb, the design styles associated with deconstruction were already beginning to appear in mainstream advertising (see fig. 18).

Heavily invested in an internecine professional conflict, and in analyses of power that foregrounded cultural politics and symbolic violence, the practitioner-theorists of the 1990s took little notice of the broader transformation of capitalism — even as this transformation made obvious inroads into the conditions of their own work. The postmodernists' celebration of vernacular design, for instance, did not extend to printing trades then in the process of disappearing. The most sustained attention Emigre lent to labor obsolescence occupies a few sentences in a 1997 essay on the type industry, which summarily dismisses these outmoded workers:

[M]any of the printers who have gone out of business over the last quarter century deserved their fate. The grassroots of the printing trade is, after all, notoriously conservative, protectionist, and sexist.99

Despite the postmodernists' lack of interest in analyses of capitalism, however, critical essays of the period are shot through with themes of alienation and autonomy on the job. Two intertwined but conflicting desiderata can be detected: designers wanted recognition for their ubiquitous but often unappreciated work, but they also hoped to transform that work into more meaningful and self-directed activity. Beneath much of the theory-speak lurked a general dissatisfaction with the social needs that design was constrained to serve. As the plainspoken designer and critic Jeffery Keedy put it, the history of the profession was a long catalog of thankless efforts at "making crappy products look interesting."100

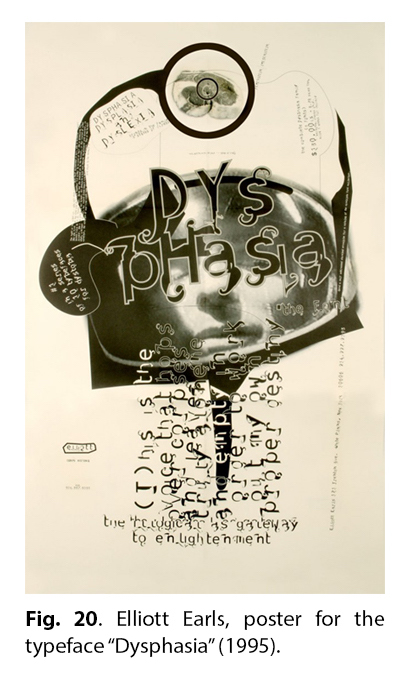

Designers also expressed discontent with work in their visual transgressions, which performatively shirked the service-oriented tasks of professional practice — even to the point of rendering language illegible. The designer's self-assertion against modernist "transparency," then, did not always depend on a grand philosophical or political mission: sometimes it was simply a visceral expression of frustration with the conditions of working life. Fittingly, this impulse was most clearly expressed by David Carson, the least theoretically-inclined of the deconstructionists. Reading over a Raygun article on the singer Bryan Ferry in the mid-1990s, Carson grew so disgusted by the poor quality of the writing that he decided to print the entire article in a dingbat font (see fig. 19).101 Carson may well have had "the reader" in mind here, but this gesture also highlighted his own position in the division of labor — flirting (but only flirting) at sabotage or a strike.

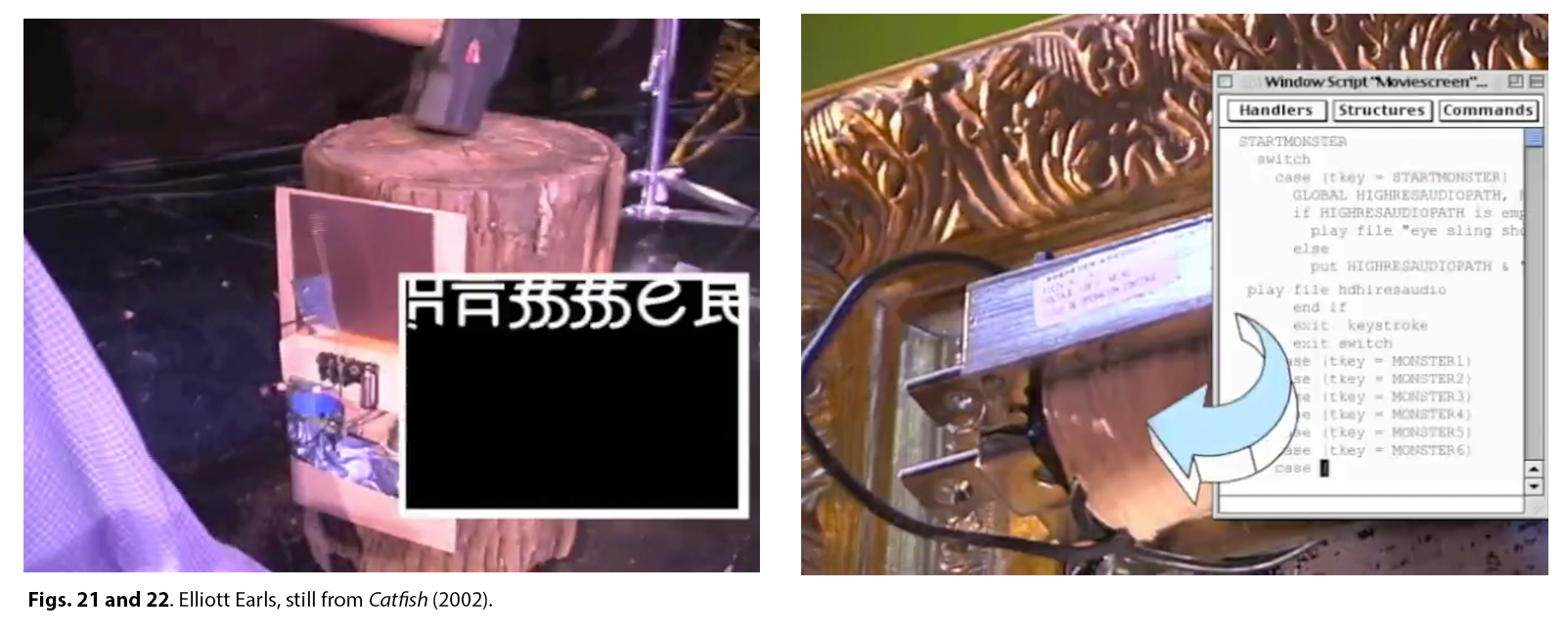

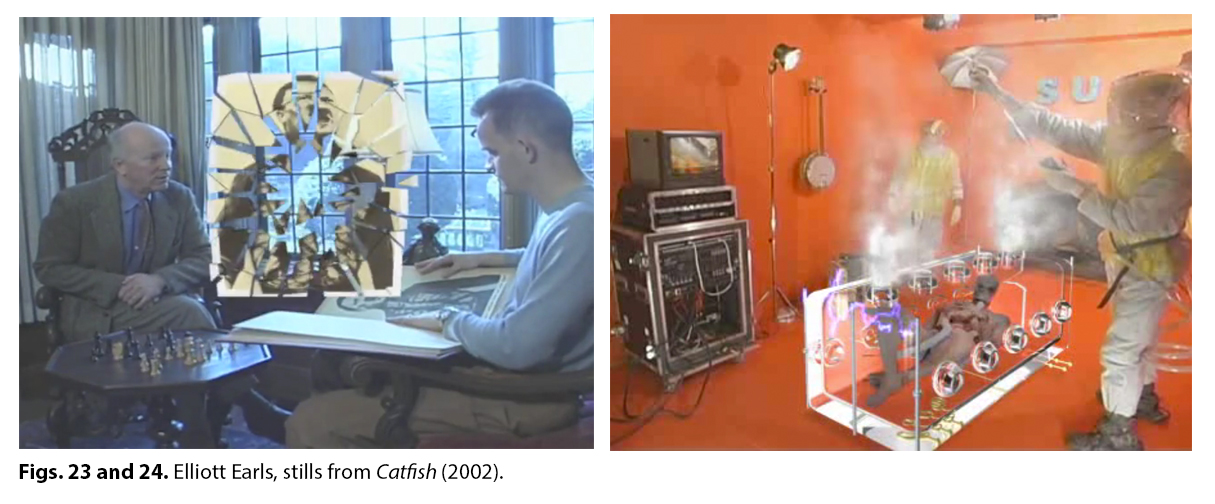

As the capacities of the personal computer grew to encompass sound, motion, and interactivity, graphic designers like Elliott Earls worked to expand the confines of the practice accordingly. Earls dabbled in font design, songwriting, and programming before reinventing himself as a filmmaker and performance artist. His 2002 film Catfish carries graphic design practice far into the territory of art; at the same time, it is also saturated with references to labor.102 Throughout the film, Earls juggles power tools and musical instruments. When he is not depicted laboring in one way or another, he is seen dejectedly contemplating his failures; "I was so close I could taste it," he intones a cartoonish working-man's drawl, just as the curtain lifts on film's main act.

As the capacities of the personal computer grew to encompass sound, motion, and interactivity, graphic designers like Elliott Earls worked to expand the confines of the practice accordingly. Earls dabbled in font design, songwriting, and programming before reinventing himself as a filmmaker and performance artist. His 2002 film Catfish carries graphic design practice far into the territory of art; at the same time, it is also saturated with references to labor.102 Throughout the film, Earls juggles power tools and musical instruments. When he is not depicted laboring in one way or another, he is seen dejectedly contemplating his failures; "I was so close I could taste it," he intones a cartoonish working-man's drawl, just as the curtain lifts on film's main act.

The bulk of Catfish follows a structure first developed in his 1998 CD-ROM Eye Sling Shot Lions, in which pop-up windows litter the viewer's screen with songs, drawings, videos, and experimental typefaces (see fig. 20).103 The centerpiece of the film is a live performance in which handmade props are used to trigger preprogrammed events. In Earls's translation of a work of programming into a performance — thus requiring the bodily presence of the artist and his audience — immaterial or barely-perceptible actions are amplified and exaggerated. At one point, what may have been a single mouse click is re-performed as hard labor: Earls heaves a sledgehammer onto a log conspicuously rigged with wires, setting off an animation that simply says, "This hammer is painfully heavy" (see fig. 21). Later, Earls steps onto a trigger and a ricochet sound effect announces a pop-up window containing animated lines of code — surrounded, further, by arrows that describe inputs and outputs. The windows fade in and out to keep whatever they are describing at least partially visible, but in many cases the simple stage effects are nearly obliterated by layers of evidence and explanation (see fig. 22). In contrast to the consumer software from which these elements originate, no piece of Earls's "hardware" works quietly behind the scenes; everything has to perform and everything demands to be recognized.

The bulk of Catfish follows a structure first developed in his 1998 CD-ROM Eye Sling Shot Lions, in which pop-up windows litter the viewer's screen with songs, drawings, videos, and experimental typefaces (see fig. 20).103 The centerpiece of the film is a live performance in which handmade props are used to trigger preprogrammed events. In Earls's translation of a work of programming into a performance — thus requiring the bodily presence of the artist and his audience — immaterial or barely-perceptible actions are amplified and exaggerated. At one point, what may have been a single mouse click is re-performed as hard labor: Earls heaves a sledgehammer onto a log conspicuously rigged with wires, setting off an animation that simply says, "This hammer is painfully heavy" (see fig. 21). Later, Earls steps onto a trigger and a ricochet sound effect announces a pop-up window containing animated lines of code — surrounded, further, by arrows that describe inputs and outputs. The windows fade in and out to keep whatever they are describing at least partially visible, but in many cases the simple stage effects are nearly obliterated by layers of evidence and explanation (see fig. 22). In contrast to the consumer software from which these elements originate, no piece of Earls's "hardware" works quietly behind the scenes; everything has to perform and everything demands to be recognized.

Despite the one-man-band conceit of the performance, Catfish's final credit roll is lengthy. Aside from a handful of supporting actors, Earls lists himself on nearly every line. He is Catfish's director, producer and funder; he is the sound designer, who also plays every instrument heard in the soundtrack; he is the programmer of all "on-stage hardware" and the DVD interface itself; and he is the stylist for makeup, hair, and wardrobe. Earls frenetically switches roles in both the film and its production, leaving the impression of a "subject wanting too much and trying too hard" — or, a character type that Sianne Ngai has identified as "the zany."104 For Ngai, the "intensely affective and physical" energy of zaniness speaks most directly to the experience of post-Fordist work insofar as it captures the "politically ambiguous intersection between ... acting and service, playing and laboring."105

Despite the one-man-band conceit of the performance, Catfish's final credit roll is lengthy. Aside from a handful of supporting actors, Earls lists himself on nearly every line. He is Catfish's director, producer and funder; he is the sound designer, who also plays every instrument heard in the soundtrack; he is the programmer of all "on-stage hardware" and the DVD interface itself; and he is the stylist for makeup, hair, and wardrobe. Earls frenetically switches roles in both the film and its production, leaving the impression of a "subject wanting too much and trying too hard" — or, a character type that Sianne Ngai has identified as "the zany."104 For Ngai, the "intensely affective and physical" energy of zaniness speaks most directly to the experience of post-Fordist work insofar as it captures the "politically ambiguous intersection between ... acting and service, playing and laboring."105

The zaniness of the post-Fordist designer was already evident in Rudy VanderLans's praise of the "all-around professional" who balances a dizzying stack of utterly contradictory hats.106 But what VanderLans leaves unspoken, Earls makes explicit: the "stressed-out, even desperate" effort to hold all of that together.107 If any graphic designer has approached, in McCoy's words, "roles associated with both art and literature," it is Earls. But in Catfish this achievement registers as a profound ambivalence: the film itself cannot decide whether it is a free-standing artwork or an extremely complicated design portfolio.108 Adding to this ambivalence is Earls's frequent citation of modernist Great Men, whom he greets with a consistent mixture of reverence and resentment. In the middle of the performance, Earls suddenly picks a fight with Henry Miller:

I think he's stolen my life—it's my life he's leading!

Stumbling around with French people,

and eating roots with the natives—

Those roots he eats are my roots! My family roots! [...]

"Hey Henry! ... Put down the oranges of Heironymous Bosch and let's

fight to the death like caged animals!"

In Catfish, even the quiet labor of studying one's precedents is staged as a precarious struggle. Earls meets the art historian Ernst Gömbrich, who berates him for not "risking enough" while forcing him to contemplate the antifascist photomontages of John Heartfield. Gömbrich later helps Earls self-administer a genetic experiment that will either help him grow as an artist or kill him (see figs. 23 and 24). The possibility of change thus seems to lie not in expired visions of social transformation, but in mining the self for something unique.

As works like Catfish illustrate, Earls has made the leap into that longed-for utopia in which the tools of graphic design are redirected toward ends of the designer's own choosing. There is no client or boss in the wings asking him to make the type bigger—which leaves him an open space to explore personal obsessions and myths. Yet even in this highly idiosyncratic material, Earls seems to drag along the anxious boredom of the professional, bound by an opaque social command to innovate. The graphic designer is a worker who continually labors at difference, so that the client's business can expand, so that the designer can keep working — in short, so that things can stay comfortably the same.

As works like Catfish illustrate, Earls has made the leap into that longed-for utopia in which the tools of graphic design are redirected toward ends of the designer's own choosing. There is no client or boss in the wings asking him to make the type bigger—which leaves him an open space to explore personal obsessions and myths. Yet even in this highly idiosyncratic material, Earls seems to drag along the anxious boredom of the professional, bound by an opaque social command to innovate. The graphic designer is a worker who continually labors at difference, so that the client's business can expand, so that the designer can keep working — in short, so that things can stay comfortably the same.

In opening the debate over deconstruction, Steven Heller questioned whether the new rash of "ugly" design corresponded to any genuine social "upheaval."109 Heller contrasted deconstruction to Futurism, Dada, and the counterculture — that is, to historical examples of upheaval that can be attributed to artists, youth, or the left. The late twentieth century, however, saw an upheaval in the nature of capitalist modernity itself — which was most clearly felt in changing conditions and expectations of work. As Boltanski, Chiapello, and Bernes have shown, this upheaval did incorporate dispositions that were initially nurtured by revolutionaries and artists; however, their "artistic critique" had by the 1990s largely been diverted from any radical questioning of society's material foundations. The postmodernists' attack on modernism — in both critical writing and visual deconstruction — was consistently a rejection of constraint, routine, and hierarchy. Postmodernist designers thus drew — mostly, it seems, unknowingly — on a tradition of critique that once had the capitalist organization of work in its sights. Insofar as their critique became an affirmation of the profession and of technical progress, the postmodernists built up their own progressive "master narrative" of capitalist development. In this way, they readily inherited the mantle of the universal modernizers that they claimed to have tossed aside.

J. Dakota Brown is a PhD candidate in Northwestern University's Rhetoric and Public Culture Program. He teaches art and design history at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

References

- Philip B. Meggs and Alston W. Purvis, Meggs' History of Graphic Design. 5th ed. (New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011).[⤒]

- Eve Chiapello and Luc Boltanski, trans. Gregory Elliott, The New Spirit of Capitalism (London: Verso, 2005).[⤒]

- Adrian Forty, Objects of Desire: Design and Society since 1750 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005).[⤒]

- Ibid., 24-26.[⤒]

- Quoted in Ibid., 33.[⤒]

- Adam Smith and Edwin Cannan, The Wealth of Nations (New York: Bantam Books, 2003), 10-11.[⤒]

- Ibid., 987.[⤒]

- "The man whose whole life is spent performing a few simple operations, of which the effects too are, perhaps, always the same ... has no occasion to exert his understanding, or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become." Ibid.[⤒]

- John Ruskin, "The Nature of Gothic" (1853) in The Industrial Design Reader, ed. Carma Gorman (New York: Allworth Press, 2003), 16.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- The socialist Morris, in his own words, spent his design career "ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich." Quoted in Robin Kinross, Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History, 2nd ed. (London: Hyphen Press, 2010), 45.[⤒]

- Ibid., 60.[⤒]

- Philip B. Meggs and Alston Purvis, Meggs' History of Graphic Design, 4th ed. (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2006), 186.[⤒]

- Robin Kinross, Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History, 60.[⤒]

- Frank Lloyd Wright, "The Art and Craft of the Machine" (1901) in The Industrial Design Reader, ed. Carma Gorman (New York: Allworth Press, 2003).[⤒]

- Ibid., 57.[⤒]

- Ibid., 59. Here Wright is making a point more famously and forcefully made nine years later by Adolf Loos, but one which does not depend on the facile Eurocentrism that one encounters in "Ornament and Crime." See Adolf Loos and Adolf Opel, Ornament and crime: Selected essays (Riverside: Ariadne Press, 1998).[⤒]

- Aleksandr Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and Aleksei Gan, "Who We Are: Manifesto of the constructivist group" (1922) in Graphic Design Theory: Readings From the Field, ed. Helen Armstrong (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), 23.[⤒]

- Meggs and Purvis, Meggs' History of Graphic Design, 315.[⤒]

- El Lissitzky, "Our Book" (1926), in Graphic Design Theory: Readings From the Field, ed. Helen Armstrong (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), 30.[⤒]

- Ibid., 26.[⤒]

- Meggs and Purvis, Meggs' History of Graphic Design. 323.[⤒]

- Ibid., 356.[⤒]

- Ibid., 342-343, 345-347[⤒]

- For the first three years, the IDCA ran under an unchanging title: "Design as a Function of Management." Wim de Wit, "Claiming Room for Creativity: The corporate designer and IDCA," in Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975, ed. Wim De Wit (London: Lund Humphries, 2017), 23.[⤒]

- Ibid., 24, 27.[⤒]

- Meggs and Purvis, Meggs' History of Graphic Design, 321.[⤒]

- "That it [machine production] is 'modern' is by no means the same thing as saying that it has value or even that it is good; much more is it evil. But since we are unable to manage without machine production, we must accept its products simply as facts, without worshipping them on account of their origins." Quoted in Kinross, Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History, 130.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Antonio Gramsci, "Americanism and Fordism," in The Antonio Gramsci Reader, ed. David Forgacs (New York: NYU Press, 2000), 295.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid., 296.[⤒]

- Georg Lukács, "Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat," in History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1968), 98-100.[⤒]

- Ibid., 98.[⤒]

- Ibid., 99.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- C. Wright Mills, "Man in the Middle: The designer," in Power, Politics and People: The collected essays of C. Wright Mills, ed. Irving Horowitz (New York: Ballantine Books, 1967), 382.[⤒]

- Ibid., 374.[⤒]

- Wit, "Claiming Room for Creativity," 23.[⤒]

- Frank Romano, History of the Phototypesetting Era (San Luis Obispo: Graphic Communication Institute, 2014), 43.[⤒]

- For more on the last days of the ITU, see my interview with typesetter and union organizer Michael Neuschatz, "As the Ink Fades: An Interview with Michael Neuschatz," Jacobin. Accessed October 15, 2018.[⤒]

- The night that the film documents occurred two years earlier on July 1, 1978. "Etaoin Shrdlu" was a string of letters punched into the machine to indicate a typing error. Farewell Etaoin Shrdlu: An Age-old Printing Process Gives Way to Modern Technology, dir. David Loeb Weiss, Brooklyn, NY: D.L. Weiss, 1980.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Greg Castillo, "Establishment Modernism and its Discontents: IDCA in the 'long sixties.'" In Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975, ed. Wim de Wit (London: Lund Humphries, 2017).[⤒]

- Ibid., 56.[⤒]

- The absorption of a century's worth of printing trades into the personal computer represented a radical aggregation of productive force that has had repercussions far beyond design practice. As I type out this paper, I freely traverse what was once a highly-regimented chasm separating the act of writing from that of preparing print-ready type. This set of capabilities would not only become the basis of the new design software, but also of communications media that are by now deeply integrated with everyday life. [⤒]

- Alan Liu's chapter on "Information as Style" addresses the same period I describe here. Where I emphasize the postmodernist response to modernism (which began before the advent of the personal computer), Liu's analysis of "antidesign" from the 1970s forward stresses "the crisis triggered in print design by digitization" more broadly construed (219). Alan Liu, The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 216-222.[⤒]

- Dushko Petrovich, "Dushko Petrovich: Emigre." Open Space. Accessed October 20, 2018.[⤒]

- An initiative called the "Apple / Design School Consortium" installed a roomful of donated hardware and software and offered a few days of seminars to get the lab up and running. Interview with Glen Suokko, Emigre 11, 8.[⤒]

- Rick Poynor, "Reputations: Katherine McCoy," Eye 16 (1995): 13.[⤒]

- Katherine McCoy, "American Graphic Design Expression," Design Quarterly 148 (1990): 16.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Poynor, "Reputations: Katherine McCoy," 16.[⤒]

- Steven Heller, "Cult of the Ugly," Eye 9.3 (1993): 155-159.[⤒]

- Ibid., 156.[⤒]

- Ibid., 159.[⤒]

- In 1990, design critic Rick Poynor founded the British magazine Eye, which kept a close record of the new developments without committing as wholeheartedly; whereas Emigre was scarcely edited and its format changed frequently, Eye was both more organized and more sober. The two magazines published many of the same practitioner-critics; together they staked out a middle ground between trade publications like Print or Communication Arts and academic journals like Visible Language or Design Issues. [⤒]

- Blauvelt has since returned to Cranbrook; he has been the director of the Cranbrook Art Museum since 2015.[⤒]

- Blauvelt, Andrew. "The Cult(ivation) of Discrimination," Emigre 31 (1994): n.p.[⤒]

- Heller, "Cult of the Ugly," 159.[⤒]

- Ibid., 155.[⤒]

- Blauvelt, Andrew. "The Cult(ivation) of Discrimination," n.p.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Fellow Readers accompanied the first reprinting of Kinross's Modern Typography.[⤒]

- "[F]ellow-readers, to whom [vernacular speakers] were connected through print, formed, in their secular, particular, visible invisibility, the embryo of the nationally-imagined community." Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1983); quoted in Kinross, "Fellow Readers," 346.[⤒]

- Ibid., 350.[⤒]

- Ibid., 357-360.[⤒]

- Ibid., 335.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid., 337.[⤒]

- Ibid., 344, 345.[⤒]

- Ibid., 344-345.[⤒]

- Anne Burdick and Louise Sandhaus, "Know Questions Asked," Emigre 34 (1995), 52-63. Burdick is the current chair of the graduate Media Design Program at Art Center College of Design. Sandhaus is a professor and former Program Director at the Graphic Design Program at California Institute of the Arts.[⤒]

- Ibid., 55.[⤒]

- Ibid., 58. As the designer, editor, and publisher of "Fellow Readers" and Modern Typography, Kinross thus comes under fire for his own design approach. Kinross's Hyphen Press, founded in 1980, published more than 30 volumes, as well as a music series. The press closed in 2017.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Emigre publisher and designer Rudy VanderLans is given shared credit for the essay's authorship on its title page.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid., 60.[⤒]

- Kinross, "Fellow Readers," 343.[⤒]

- Andrew Blauvelt, "In and Around: Cultures of Design and the Design of Cultures Part I," Emigre 32 (1994): 7-14; "In and Around: Cultures of Design and the Design of Cultures Part II," Emigre 33 (1995): 2-23.[⤒]

- Andrew Blauvelt, "Desperately Seeking David, or, Reading Ray Gun, Obliquely," Emigre 38 (1996): 61-64.[⤒]

- Ibid., 61.[⤒]

- Ibid., 62.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid., 62-63.[⤒]

- Throughout this essay, but here in particular, I am indebted to the late Moishe Postone. See Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A reinterpretation of Marx's critical theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.[⤒]

- Quoted in "3 ... Days at Cranbrook," Emigre 19 (1991): n.p.[⤒]

- Chiapello and Boltanski, The New Spirit of Capitalism.[⤒]

- Jasper Bernes, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).[⤒]

- Ibid., 155.[⤒]

- Ibid., 9.[⤒]

- Andrew Blauvelt, "Towards Critical Autonomy, or Can Graphic Design Save Itself?" Emigre 64 (2003): 39.[⤒]