Issue 1: Deindustrialization and the New Cultures of Work

Contemporary TV demonstrates a conspicuous interest in two related kinds of employment: tipwork (waiting tables, bartending, making espressos) and the more recent form of work termed "gigwork" (temporary, project-based freelance work, especially the sort mediated via online platforms). On recent fictionalized shows including Atlanta, Broad City, Crashing, Easy, Girls, The Good Place, BoJack Horseman, High Maintenance, Insecure, It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Master of None, Silicon Valley, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Togetherness, Two Broke Girls, Search Party, and Westworld, we find characters driving for Uber, serving drinks, working for TaskRabbit or Mechanical Turk, making espressos, renting their bedrooms on Airbnb, delivering consumer goods, and waitressing. On the "reality" side of contemporary TV, likewise, the newest genre is the service work show.1 Vanderpump Rules, for instance, depicts the staff of LA's SUR restaurant and is currently filming its seventh season; Below Deck is about the crew members on chartered yachts, and Apres Ski and Timber Creek Lodge feature the service staff of an "ultra-luxurious ski lodge." Each episode of Below Deck begins as the "yachties" are informed of their next group of "clients"; it then depicts the various tensions that emerge on the 3-5 day voyage and ends with the presentation of a group tip which is divided equally among the staff. This climactic act of tipping enables the show to see the customers as the tipworkers themselves do — as a trivial, temporary means to an end or a necessary evil. Below Deck's representation of the alienation specific to tipwork — where one has not one stable employer but many temporary bosses whose desires are as unpredictable as are the tips they pay you to meet them — is, I will suggest, representative of the contemporary genre of tipwork TV.

Of course, TV's interest in work and the workplace is not new. The so-called "First Golden Age of Television" of the 1950s was largely dominated by variety shows and domestic sitcoms, and TV scholars like Serafina Bathrick, Ella Taylor, and Michael Tueth have noted that the workplace series didn't really "come into its own" until The Mary Tyler Moore Show, which ran from 1970-1977.2 Taylor influentially argues that the workplace TV of the 1970s combined the older domestic narrative with a new workplace narrative: the result was what she calls the "work-family series" which imagined "a workplace utopia whose most fulfilling attributes are vested not in work activity but in close emotional ties between coworkers." Shows like Mary Tyler Moore, M*A*S*H, WKRP in Cincinnati, Taxi, and The Bob Newhart Show, she claims, construct an ethic of professionalism and imagine the familial workplace not as a "corridor of power" or corporate enclave but rather as a "cozy ... corner of the organizational world in which human worth was measured by loyalty and humanistic values."3 The workplace comedies of the 1970s-1990s, Tueth similarly observes, largely featured "white collar environments with main characters who are ... professionals: psychologists, physicians, educators, politicians, designers, lawyers, journalists."4 Those same professional jobs would come to dominate the workplace drama too, as 1980s and 1990s shows like LA Law and West Wing imagined "work-families" even in workplaces that were indeed within the "corridors of power."

Between the 1970s and the 1990s a smaller set of workplace sitcoms featured working-class characters — and, sometimes, less "cozy" workplaces, especially in service sector jobs. Yet sitcoms about low-wage service work from this period differ from the contemporary genre of tipwork TV I identify here insofar as they tend to represent service work — its material conditions, its social relations, and its professional possibilities — in basically positive terms. In particular, the scant number of service-work shows that appeared in the 1970-1990s tend to represent tipwork either as entrepreneurial investment (being a server who also owns the business, as on Cheers and Newhart); as vocation (as on Taxi, since, as Tueth observes, Alex Reiger's status as the "central, mimetic character with whom the viewers could identify" seems directly linked to the fact that he's also the only character who views taxi-driving as a vocation); or as a means to a surrogate family (one that extends to customers and even to bosses, as on Cheers or the multiple domestic-service sitcoms — Benson, The Nanny, Mr. Belvedere, Charles in Charge, Who's the Boss? — popular in the 1980s and 1990s).5 Moreover, despite the importance of shows like Taxi and Roseanne, shows about working-class life, whether in service work or otherwise, were not especially common: Richard Butsch notes that between 1946 and 1990, "of 262 domestic situation comedies, only 11 series featured a blue-collar employee ... when clerical and service workers are included, 'working class series' are still a very meager 11% of all series; by contrast, 45% represented professional heads of household."6 By the early 2000s the working-class comedy (whether domestic or workplace) was giving way to shows like Friends, Will & Grace, and Sex and City, which focused largely on professional or creative work.7 Concluding the chapter on workplace TV in his 2005 study, Tueth notes that "on many of the most successful new comedies, work does not occupy much time or attention. Perhaps the workday is over. Perhaps it is time to play."8

Tueth's optimistic speculation — not to mention the shows he describes — feels symptomatic of the financial-bubble years of the late 1990s and early 2000s, but that bubble would eventually pop. Thereafter, people not only worked more than ever, they worked for ever-lower wages, and ever-more often for tips. Between the early 1990s and 2018, the number of people working in food services doubled; today 1 in 9 workers is employed in the "Leisure and Hospitality" sector.9 Since the early 1990s, when Cheers went off the air, nearly half of job growth has been in low-paid service work, and as of 2016, the combination of retail, leisure, hospitality, and "personal" service makes up around 23% of all employment.10 The shows I discuss here thus respond to these fast-changing conditions of contemporary work, and mark a new era — we might call it millennial — of workplace television, departing from the "work family" narrative of the 1970s-1990s waged-workplace sitcom, from the professional emphasis of the 1970s-1990s salaried-workplace drama, and from the wounded nostalgia that Michael Szalay discerns in post-2000 quality TV about managerial labor.11 According to a 2011 Economic Policy Institute (EPI) report, tipped workers are nearly twice as likely as non-tipped workers to live under the poverty line; the median wage for tip-workers (including tips) is $10.22 as compared with $16.48 for workers overall.12 Under these conditions, it is scarcely surprising to find few TV representations of friendly, familial relationships between managers and tipworkers; tipworkers' actual families, after all, are significantly more likely to rely on public benefits than the households of non-tipworkers.13 In this sense, the most apt — if also the most extreme — representation of the experience of contemporary service work is perhaps a dramatic show like HBO's Westworld, with its slave-like "hosts" subject to perpetual violence at the hands of the customer "guests."

If service work has a history on contemporary TV, gigwork largely does not, in part because gigwork itself is fairly new.14 The use of "gig" to describe a temporary work arrangement dates to the early-twentieth century, when it was used to describe the sort of "one-night stand" for which a musician might be hired. But as the narrowness of this earlier definition suggests, "gigwork" was not used to describe what the Bureau for Labor Statistics (BLS) terms "alternative employment" until relatively recently. The category of "contingent work" — work without "an implicit or explicit contract for long-term employment" — was developed by a BLS economist in the mid-1980s, but as Louis Hyman explains, the BLS didn't conduct a "serious survey of contingent workers" until a decade later, defining contingent work as "those who do not have an implicit or explicit contract for ongoing employment." Since that 1995 survey, Hyman argues, firms' use of gigwork has expanded such that contingency now defines a growing range of occupations (and has become a way to reduce labor costs in a growing number of industries), yet the BLS has not changed its definition to catch up to those changes.15 By the BLS's account, then, only 3% of all employment is contingent work, while the broader category "alternative employment arrangements" under which contingent work is subsumed makes up around 13%. However, the BLS's recent figures do not include "individuals who found short tasks or jobs through a mobile app or website and were paid through the same app or website": that is, they do not account for people working for companies like Uber and TaskRabbit. They also don't include people who work in the gig economy but not as a "primary" job.16 Here, then, I use the term gigwork (rather than contingent work) to include alternative employment, contingent work, and especially the very new forms of task-based, app-mediated gigwork not yet accounted for by the BLS but of particular interest to contemporary TV.17 Employment surveys using a similarly expansive definition include a report by the Upwork/Freelancers Union which estimated that 35% of the US workforce — 55 million people — freelanced in 2016; the portion of that group most likely to have performed tech-mediated gig work are the 33 million who are "traditionally" employed but also "moonlighting" or "temping,"18 By another survey's account, gigwork is now the primary form of employment for 5 million people in the US, a number predicted to grow to 10 million by 2021.19 Almost every new job created in the 10 years since the recession of 2007-2009 was in "alternative employment" or gigwork.20

It makes sense, then, that contemporary TV is obsessed with the transformative novelty of app-mediated gigwork. Even still, these forms of employment sometimes appear on TV only as an absent presence. In a series of episodes of Season 4 of Silicon Valley, for instance, character Dinesh helps sell a lucrative porn-blocking app he helped to develop; when the deal goes awry, he is forced to work long hours tagging online "dick pics." In reality, this is precisely the kind of job a trained coder — especially a successful coder with a stake in the company — would never do. This kind of job is almost always farmed out via gigwork platforms like Mechanical Turk, whose "on-demand, scalable workforce" has tagged images for clients ranging from photosharing platform SnapMyLife to the US Army Research Laboratory, and which has been especially key to getting porn (and Nazis) off of platforms like YouTube. Elsewhere, gigwork appears on contemporary TV via a kind of allegorical recoding: while Janet — the operational mainframe for heaven and hell and personal assistant to the gods on The Good Place — is often described by reviewers as a kind of personified Alexa, able to answer any question, she actually functions more like a TaskRabbit, "designed to make your life easier" by fetching anything from ice cream to cactuses. Janet's deactivation at the end of Season 1 is thus akin to the "deactivation" (their term) that Taskers face if they don't follow the app's rules.

At other points, however, gigwork appears so explicitly that the real-life apps themselves are named. On Season 4 of Silicon Valley, for instance, Monica — recently laid off from her work as second-in-command at the Valley's largest VC operation — goes grocery shopping and notes that she's obviously a loser because she's "the only person in this store actually buying stuff for myself"; the camera then pans to gigworkers wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the logos of TaskRabbit, Postmates and Instacart. Of course, the reality effect provided by these references is undercut by the actual reality that even though she's temporarily unemployed, entrepreneurial Monica is surely far better off than the gigworkers who surround her in the fruit and vegetable aisle, not least because none of them could afford to live in the titular Silicon Valley. Similar brand specificity marks other references to gigwork: Kimmy on Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt works first for Uber and then for TaskRabbit; Issa on High Maintenance and various characters on Easy drive for Lyft; Dylan on American Vandal works for Postmates; characters on Easy, High Maintenance, and Broad City rent out their apartments on Airbnb. These shows also depict characters (often the same characters) hiring gigworkers themselves: Billy on Difficult People employs "Chore Rabbits" and basically everyone on TV takes Uber and Lyft at some point.

This essay emerges out of a curiosity about how these references to tipwork and gigwork shape the contemporary TV shows in which they appear. It begins by tracking a process I term the "tipworkification of labor." I describe first the means by which tip income was formalized as a legally recognizable portion of the wage, in 1966 and 1996 amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act. The idea of "tipworkification" not only describes efforts to reduce the labor costs for service-industry employers, it also yokes these changes in the wage to the increased importance of gigwork. Tipwork's low wages have arguably provided the gig economy with a population of workers willing to take on second or third jobs doing things like driving for Lyft. Gigwork also borrows many of the formal features of tipwork, including the lack of basic workplace protections and job security. Following this economic history, I turn to tipwork TV, arguing that the tipworkification of labor has transformed popular narratives about work. Shows about service work have moved increasingly away from their prior affinity with shows about professional work and its vocational imaginary in order to better grasp the specific forms of exploitation experienced by tipworkers in the contemporary economy. In so doing, they have also turned away from both quality TV's dramatic seriality and from the sitcom's comedic repetition. If serial continuity is the narrative correlative of professional development or vocational achievement, while the classic sitcom's repetitive continuity is the correlative of endless, unchanging, but also stable waged or salaried work, then the episodic, discontinuous, and occasionally surrealist structures of much contemporary TV register the episodic, fragmented, and profoundly insecure experience of tipwork and gigwork.

The Tipping Point

Although we tend to see industrialization as the period in which wage systems and contracts were fully standardized, Amy Dru Stanley reminds us that nineteenth century labor arrangements tended to rely "on contract rules that were written and unwritten, spoken and unspoken, formal and informal."21 As Maurice Dobb suggests in his classic Wages, the dominant method of wage payment under early industrialization was thus payment by results — the method Marx calls "piece rate" and that shares some of the formal features of tip wages. 22 Yet as Eric Hobsbawm argues in his influential essay "Custom, Wages, and Workload in Nineteenth Century Industry," by the late-nineteenth century workers had learned what he calls "the rules of the game" — namely "a fair day's wage for a fair day's work."23

By the end of the Great Depression, workers had begun to apply this maxim to collectively demand what the market would bear, while employers turned to more efficient forms of scientific management. With the development of what Hobsbawm terms the "scientifically calculated and controlled output norm per time unit" made possible by Fordist assembly line structures and Taylorized management, flat time-based wages became more prevalent.24 In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) was passed, and it too depended on an hourly accounting system to establish its averages, setting a national minimum wage of $.30 an hour and a standard 40-hour workweek for full-time employees.25 A series of amendments over the ensuing decades would steadily raise the minimum and also include more categories of workers. The FLSA amendments of 1966 were the most radical in terms of inclusion, bringing farmworkers and workers in hospitals, nursing homes, schools, transit, taxi services, restaurants, and hotels under the protection of minimum wage laws. For the last of these, however, a proviso remained: if an employee regularly received more than $20 per month in tips, the employer could apply those tips towards up to 50% of the minimum wage, effectively setting a "tip credit" or "subminimum" wage. EPI Researchers Sylvia Allegretto and David Cooper explain:

Unlike temporary subminimum wages (such as those for students, youths, and workers in training), the "tip credit" provision afforded to employers uniquely established a permanent sub-wage for tipped workers ... The creation of the tip credit ... fundamentally changed the practice of tipping. Whereas tips had once been simply a token of gratitude from the served to the server, they became, at least in part, a subsidy from consumers to the employers of tipped workers. In other words, part of the employer wage bill is now paid by customers via their tips.26

Tips were not legally recognized as a form of wage payment prior to 1966, but of course tipping itself was not new. While there is some debate among historians about the origins of tipping, it seems to have emerged in the late middle ages and to have been codified during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the practice of giving sums of money (known as vails) to the servants of a private house when one had been an extended guest, a scenario rather like the one that structures Below Deck.27 Workers themselves typically supported the practice, often by force: in the mid-eighteenth century in Scotland, a group of gentry and nobility attempted to abolish the practice and the servants rioted, breaking windows and swinging bats. With the rise of industrialization, the portion of the population employed in this kind of domestic service declined, but the number of commercial eating and drinking establishments, hotels, and trains increased dramatically: thus "a greater proportion of people ... found themselves in tipping situations" and the practice of tip-giving moved downward class by class.28

The exploitation of tipped employees has also often been racialized. One of the leading proponents of tip wages in the early twentieth century was the Pullman Company, which exclusively hired black men from the South because, in the words of one executive, "the southern negro is more pleasing to the traveling public. He is more adapted to wait on people and serve with a smile." This clearly registers the sense that there was a deep connection between the non-waged work of in-person service and the non-waged work of chattel slavery, but there was a more material interest at stake as well: Pullman not only paid porters significantly less than a living wage, they announced that seemingly shameful fact whenever possible, such that a St. Louis Republic editorial could write, in 1915, "Other corporations before now have underpaid their employees, but it remained for the Pullman Corporation to discover how to ... induce [the] public to make up, by gratuities, for its failure to pay its employees a living wage."29 That is, Pullman relied on the normative force of what E.P. Thompson called a "moral economy" among the working class, who share a "popular consensus" as to "social norms and obligations."30

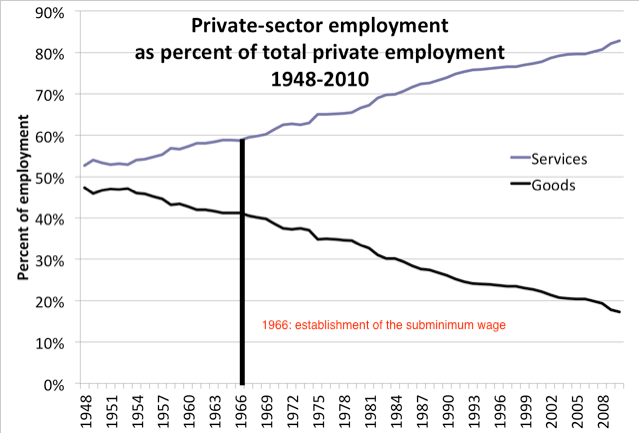

Pullman's practice of depending on customers to ensure that workers took home Hobsbawm's "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work" was legalized and codified by the 1966 FLSA amendment. Much as Pullman was able to profit immensely by relying on consumers' tacit acceptance of this imposed moral economy, the setting of a subminimum wage for the restaurant and hospitality sector was a massive labor-cost subsidy for the restaurant, hotel, and leisure industry, one that arguably contributed to the transformation of the US economy from a manufacturing to a service economy, as indicated in the graph below.

Fig. 1. Employment in services provisioning versus goods provisioning as percentages of total private employment, 1948-201031

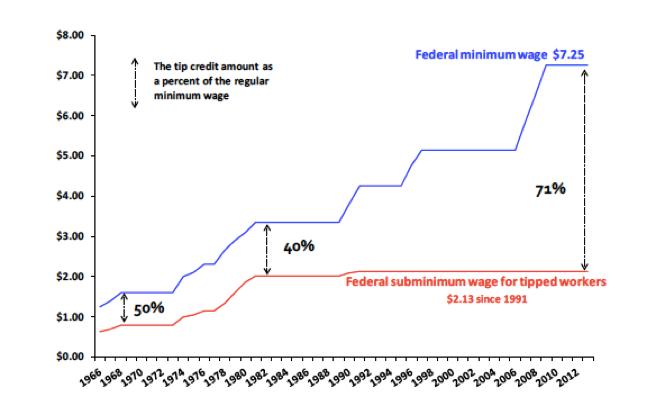

The subminimum wage's labor-cost subsidy for the service industry got even bigger with the passage of the 1996 Minimum Wage Increase Act (MWIA). The MWIA was championed by the National Restaurant Association (NRA), then headed by Godfather's Pizza CEO (and future presidential candidate) Herman Cain.32 It's little wonder the NRA supported it: the MWIA eliminated the FLSA provision that pegged the tipped minimum wage to 50% of the full minimum wage, instead fixing it at $2.13 an hour (the rate set in 1991, which is still the rate today in 2018). As the graph below demonstrates, it is now only 29% of the federal minimum wage.33

Fig. 2. Federal minimum wage and subminimum wage for tipped workers (1966-2013).34

As Allegretto and Cooper write, the MWIA amendment further "reduce[d] employers' future wage bill by locking in a low base wage for tipped workers that would remain fixed, even as prices rose or the regular minimum wage was increased."35 It also shifted responsibility for an increasing portion of tipped workers' wages from employers to customers much as Pullman had done in the early-twentieth century. In 2014, for instance, the hotel chain Marriott partnered with former California First Lady Maria Shriver's non-profit "A Woman's Nation" to create "The Envelope Please," a "person-to-person" initiative seeking "to boost the incomes of women working as hotel housekeepers" by "enabling hotel guests to express their gratitude by leaving tips and notes of thanks for hotel room attendants in designated envelopes provided in their rooms."36 Marriott — which had reported net incomes for the previous year of more than $600 million, up 10% from the year before — was, not surprisingly, eager to participate in this effort promising to raise their employee's incomes (and thus potentially improve their retention rates and productivity) without increasing the corporation's labor costs.

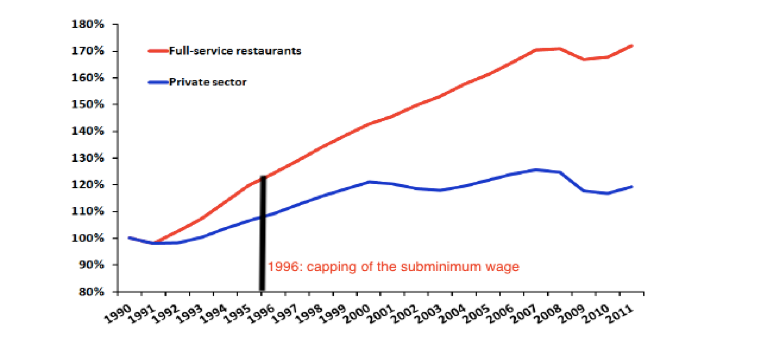

Shifting a larger portion of workers' incomes to tips not only saves employers from having to pay a fair wage (and the state from having to guarantee one), it also reduces the cost of managing and monitoring workers. If one's income depends on fast, attentive, careful service, one is highly likely to oversee oneself fairly effectively, a process Jasper Bernes evocatively terms "self-harrying."37 Finally, while employers are legally required to ensure that tipped workers still earn at least minimum wage, enforcement of this requirement remains lax, and tipped workers are particularly vulnerable to wage theft.38 The graph below thus suggests that by reducing management costs, reducing labor costs, and making wage theft easier, the subsidy provided to the hospitality and restaurant sector via the subminimum wage aided the growth of a decidedly low-wage industry as a major portion of the US economy.

Fig. 3 Employment growth in the private sector and full-service restaurant industry before and after the capping of the subminimum wage (1990-2012)39

Given that tipworkers work fewer hours, have less paycheck stability and significantly higher poverty rates, and are more likely to rely on government assistance than waged workers, how do they make ends meet? Many of them have ended up in the gig economy. According to a recent Federal Reserve study, about 30% of working-age adults have engaged in gigwork: of those, 40% use it to supplement income from another job, and of those, 65% say this extra money is very important to their family income.40 For many households, gigwork has thus been a way to compensate for decades of wage stagnation, much as cheap consumer credit was from the 1990s until the crash of 2008. The boom in low-paid service work may even have provided the gig economy with a workforce desperate enough to get "overtime" in the form of a second or third job. This structural form of "self-harrying" makes life in the gig economy not only desperate but also dangerous, since the employment model's "flexibility" incentivizes potentially fatal levels of bodily risk. This spring, for instance, Caviar deliverer Pablo Avendano was killed while biking on a rainy night after receiving a message from the service encouraging couriers to "come out" despite the bad weather with the promise of surge-pricing bumps and "preferred treatment."41

Tipwork does more than just provide the gig economy with a ready pool of workers looking for more work, it also provides gigwork with its employment model. For one thing, gigwork is often literally tipwork. Most apps — including Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, GrubHub, Instacart, Caviar, and Postmates — offer customers a "suggested tip amount" of 15%-20% which, since these companies also take a cut of around 25-30% of the service fee paid to the gigworker, makes tips a not-insignificant portion of gigworkers' income.42 Gigwork also replicates many of the key features of tipwork: no paid leave, insurance, retirement benefits or overtime protections; unpredictable scheduling; and weekly work hours below what the employee would prefer.

Here, then, I use the term "tipworkification" to describe the gradual erosion of the wage contract as the model for employment relations, an erosion that also led to the attenuation or superannuation of the institutions that once mediated between workers and employers (the union, the state, and middle-management). Neither tipworkers nor gigworkers are likely to have their wages protected or guaranteed by a union or by collective bargaining. Only 1.7% of workers in "food service and drinking places" are unionized; among all occupations, only farming and retail sales (also often a "pay by results" occupation) have lower rates of unionization. While gigworkers in the UK recently made some hard-fought gains as a result of wildcat strikes and militant bottom-up campaigns, US law classifying gigworkers as independent contractors rather than employees perforce denies them collective bargaining rights and makes unionization very hard.43 The wage systems of tipwork and gigwork are also not protected by the state in the same way wage contracts are. Gigworkers, of course, have no minimum wage protections at all. But after the capping of the subminimum wage in 1996, the same is basically true for tipworkers: fixed at its 1991 rate, the tipped wage no longer even pretends (as the federal minimum does, albeit with little credibility) to protect the worker's right to what Roosevelt, in advocating for the FLSA, termed a "living wage" — "more than a bare subsistence level ... the wages of a decent living."44 Tipwork and gigwork are also no longer mediated by a single principle-agent relation, as is the wage contract between a worker and a firm. In his seminal work of principle-agent theory, Functions of the Executive, Chester Irving Barnard defined the "formal organization" which would determine incentive structures for workers as a deliberate, intentional, "cooperative system."45 By contrast, the "flexibility" of gigwork means that the employee has no meaningful contractual relationship to the corporation except to the extent that she must pay a portion of her income for the privilege of using their app or platform. Tipworkers and gigworkers are mostly paid by customers themselves, thus dispersing and fragmenting the "horizontal" relation of the contract between management and workers.

I use the term "tipworkification" cautiously. Certainly, more obvious terms abound — gigification or tempification, for instance — and many of the forms of work that fall under the broad category of temporary, post-wage-contract work are not literally tipwork. I use tipworkification, then, for two reasons. First, I want to resist the presentism common to discourse of the disruptive "gig economy" — at least the part of it associated with online labor platforms — and to locate the origins of this trend further back. Gigwork, I am suggesting, emerges not just from the reorganization of industrial and office labor in the 1960s by temp organizations like Manpower, but also from the attenuation of wage protections that also aided the rise of the low-wage service sector, first in 1966 and again in 1996.46 Attending to these transformations reveals a rarely-remarked origin point (though not the only one) for the attenuation of wage and work protections and for the legalization and normalization of paying less than the federal minimum wage. Second, I use "tipworkification" to clarify my focus on the low-wage end of the broad category of "service." Better paid forms of service work (graphic design, coding, consulting, accounting, etc.) are also more and more often performed by temporary workers, and these forms of employment are subject to ever-greater precarity too. My concern here, however, is with the labor arrangements that demand exceedingly hard work, multiple jobs, or constant overtime just to earn a living wage — or where in the end, it is simply impossible to do so no matter how hard you work.47

Tipwork on TV

The tipworkification of labor shows up on TV in contradictory ways. Sometimes, TV representations of the gig economy perpetuate the fantasy that gigwork is a salutary "flexible" alternative to formal employment, one that enables workers to pursue other professional or vocational trajectories. In "Kimmy Goes to College" in Season 3 of Kimmy Schmidt for instance, Kimmy's work for TaskRabbit leads to a full scholarship to Columbia. This episode includes some clearly satiric details about gigwork — in a montage sequence of odd jobs, we see Kimmy blow up one of those huge inflated rats unions use for picket line actions. But the implication that her gigwork is just a pit-stop on the way to professional success is of course extraordinarily optimistic. More realistically, Issa on Insecure drives for Lyft in the evenings after her full-time non-profit job so she can save up enough for a security deposit on an apartment. Elsewhere, gigwork is represented as no more than a way to make ends meet before making it big in the culture industry. Thus, we find Pete, the would-be comic on Crashing, working as a street barker; Ern, the aspiring music producer of Atlanta, working an unwaged, commission-dependent sales job; and Odinaka, a character who appears in an episode of Season 2 of Easy, driving for Uber while performing stand-up. These representations of gigwork support the common belief that gigwork is a way to get some extra cash for the weekend rather than a primary job taken out of desperation, and in this sense they are no less ideological than Kimmy Schmidt's fantasy that TaskRabbit is a route to a full ride to college rather than just a way to make your monthly student loan payment.

Yet even when these shows treat gigwork optimistically, the sense that gigwork is exhausting overwork disrupts the fantasy. Although the Odinaka episode on Easy is disarmingly titled "Side Hustle," it turns out that the aspiring comedian has (besides his vocational aspirations) a tipwork job and a gigwork job, working days as a Chicago tour guide and nights driving for Uber ("It doesn't pay much, but ..."). Since far more of the episode is dedicated to his work on these two jobs than to his stand-up, it becomes unclear which is the temporary "side hustle" and which threatens to become his permanent — or permanently contingent — form of employment. Elsewhere, the bodily risks involved in "flexible" tipwork and gigwork appear more frankly: early in Season 2 of High Maintenance, for instance, the bicycle weed-delivery protagonist, called simply "The Guy," has his bike stolen and has to rely on friend who works as an Uber driver to ferry him around (for a cut of the tips), lest he find himself without an income. Later in the same season, The Guy is badly injured on the job, and we discover that he only has health insurance because his ex-wife has agreed to keep him on her plan.

If contemporary TV's interest in tipwork and gigwork appeared only at the level of content, we might dismiss it as little more than the kind of zeitgeist reality effect typical of a medium uniquely — even desperately — committed to registering its own present day. I want to claim, however, that contemporary TV's interest in these new kinds of labor is also reflected at the level of form and genre. As I suggested in the introduction to this essay, claims about the intimate relationship between TV genre and changes in the world of work have been prevalent within TV scholarship, specifically in its analysis of the oscillation between the four broad genre categories that have defined post-war fictional TV: domestic sitcoms and workplace sitcoms; family dramas and workplace dramas.48 Put simply, work has often provided TV with content, but it has also forced TV to confront specifically formal problems. Prior to the 1970s, narrative TV (that is, TV that wasn't news or variety shows) largely focused on the family, but as women continued entering the workforce and as a range of new managerial, technocratic, and professional occupations came to hold an ever-greater share of the occupational field, TV became increasingly committed to representing middle-class and working-class work (in occupations besides policing, which had long been a staple of the TV workplace imaginary).49 Yet as Ella Taylor argues, despite this

broadening of the occupational horizons of television, the workplace shows of prime-time television in the 1970s bear scant resemblance to ... the shape of the American occupational structure. This is hardly surprising: a sizable proportion of the labor force ... [performs] jobs [that] require little or no skill, creativity, or imagination and are low in pay and status ... We are unlikely to see prime-time hits entitled Keypunch, Assembly Line, or Middle Management.

The problem, she observes, is formal: "Routine work is boring; it is typically fragmented and lackluster, devoid of the dramatic charges of incident and interaction that enliven narrative." Thus the shows of the 1970s tend to focus on more apparently interesting — but also atypical — creative or cognitive professions like print and broadcast media, or psychotherapy.50 They also, as Taylor goes on to argue, represent both worklife and the workplace in salutary terms: as the site of both familial connection and self-exploration. Following on Taylor's account of the simultaneously professional and familial ethos constructed on shows representing salaried work in the 1970s, Michael Szalay has described the professional or white-collar workplace dramas that came to define "prestige TV" in the 1980s and 1990s (Hill Street Blues, ER, and The West Wing, for instance) as "domestic workplace dramas." Such shows, he argues, are symptomatic of the fantasy that "heroic professionals" could restore the pact between labor, capital, and the state forged under the New Deal — the same New Deal, notably, that produced the original FLSA.51 Like the 1970s comedies with their commitment to "dramatic incident" rather than "routine work," the 1980s and 90s dramas about professional work tend to feature what Michael Newman describes as "arcs": "plots that carry over week after week" as well as characters who "change or at least to grow" and whose stories of development — including, often, the bildung "from youth to adulthood, innocence to experience" — are "based on a more novelistic progression of events over a long direction, with episodes like chapters in an ongoing saga rather than self-contained stories."52 Character-focused TV from the 1980s and 90s largely focuses on the then-newly dominant forms of professional work — the better remunerated (but often non-unionized) upper portion of the BLS's capacious category of "service work," namely healthcare, law, civil service, management, finance — and tends to represent such work not as the grounds of a specifically classed consciousness but rather as either substitute or model for the more comfortably liberal bonds of state and family.

As Taylor's reference to routine and repetition as a problem for TV narrative suggests, working-class work (and less professionalized middle-class work like policing) is far more likely to appear in the sitcom or the procedural than in the drama. The formal conventions of the sitcom and procedural — in particular, their lack precisely of Newman's "arcs" and bildungs — make them equipped to register more routine forms of work. Both genres capture what Lauren Berlant describes as a permanent "state of animated and animating suspension" and thus register the way certain kinds of work are incredibly tedious, mundane, and repetitive (suspended in repetition), but also capable of taking over our minds and time (of animating us).53 In workplace sitcoms and procedurals, the characters effectively are their profession: the conventions, rules, and habitus of the workplace (as the framing situation or procedure itself) provides the unchanging narrative context within which particular conflicts can emerge and be resolved over the course of a single episode. The fact that we cannot separate ourselves from routine work's psychic and mental demands on us but also have a nagging sense that we are inessential to it is registered by a joke familiar to the workplace sitcom and rehearsed with particular clarity on The Office: when Pam ceases to be the receptionist, everyone calls her replacement "the new Pam" — Pam is her job, but also can always be replaced. As Tueth notes, one practical reason that workplace-family shows became more common than actual family shows is that they could have longer runs without as much concern about changes to the cast: if the actor playing The Receptionist wants out, it's as easy to replace her with another Receptionist as it is in the real world; it's harder to do the same if she's playing Mom.54

Given Taylor's observation that a show called Assembly Line would be "devoid of the dramatic charges of incident and interaction that enliven narrative," it is not surprising that working-class sitcoms often focus on low-wage service-work rather than manufacturing: waiting tables and driving taxis are routine jobs, but they are also jobs potentially replete with dramatic incident. (The procedural, with its equally routinized repetition, might in this sense be said reassure the viewer that jobs that seem to require "skill, creativity, or imagination" — District Attorney, doctor, detective — are actually just as boring as other kinds of work. This admission of professional work's repetitive daily grind is in fact what distinguishes the procedural from the more developmental professional drama.) Roseanne is the obvious exemplary case of a service-work working-class sitcom: her transition from factory worker in Season 1 to bartender and fast-food server in Seasons 2 and 3 mirrors the shift in U.S. employment in the late twentieth century from manufacturing to service, but was also arguably a formal necessity, since the writers may well have felt they needed the more dramatic and diverse interactions that could be mined from her work at the The Lobo Lounge, with its ever-changing cast of customers.

But Roseanne is also a useful example for another reason: by Season 4, she was a family-business owner (of a bike shop, co-owned with Dan) and by Season 5, both she and Dan were each owner-managers of their own enterprise (Roseanne of a diner and Dan of a construction company); by 1997's Season 9, of course, she was a lottery winner rich beyond her wildest dreams (though only, it would turn out, in fantasy — in reality, said the finale, she was a creative professional, writing a memoir about her life). Roseanne's series-arc transformation thus also mirrors the fantasy-work necessary to disavow the aforementioned shift from manufacturing to service: the show turns service work from a working-class profession into entrepreneurial investment. The show's shifts also indicate the immense ideological investment of pre-2000s workplace TV in fantasies of upward mobility and in the arcs of change and development typically thought to be foreclosed by the sitcom's repetitive endlessness.

Roseanne's interest specifically in managerial labor — managerial labor run along emphatically domestic lines, as a "family owned business" — also anticipates the transformation Szalay locates in quality TV in the wake of the 2001 and 2008 financial crises. These family dramas — or "domestic workplace dramas," as Szalay terms them — "respond to the collapse of industrial-era 'separate sphere' distinctions between home and work" not by imagining the workplace as a family but rather by imagining the family as a business. Thus "the genre sports numerous families that run family businesses or corporations (The Sopranos, Big Love, Weeds, Breaking Bad, Halt and Catch Fire, Empire, Ozark, and Succession)." Such shows dispense with the utopianism of the 80s-90s professional dramas (which, recall, imagined a restored social welfare state) and instead articulate a hopeless and melancholy "longing" for "industrial production" and "the state that once supported it." In so doing, he contends, such shows register the haunting "fear of downward mobility" that especially afflicts a "newly arrived managerial elite."55

Thus, whereas the professional drama, with its complex character arcs and serial form, captures first the aspiration and then the devastating loss of what Berlant calls "mobility as a fantasy of endless upwardness," the sitcom and procedural capture the implicitly familial comfort of predictability — a worklife that is tedious but stable, and workplaces in which "dramatic incidents" occur but can be resolved by the "situation" or "procedures" of employment itself.56 But contemporary tipwork TV, I will suggest, captures something else entirely: the loss not only of change and adventure — of bildung, arc, and achievement — but also comfort and predictability. In contrast to the professional drama, tipwork TV takes up the more poorly-paid, precarious portion of the service category, including jobs like waitressing and bartending once common to the traditional workplace sitcom. In contrast to the workplace sitcom, it does so with a far less "cozy" or "familial" sense of working conditions, with a far more attenuated sense of future upward mobility, and with a far less comfortable sense of employment's stability (or, in the case of the gigwork shows, with no faith in stability at all). Indeed, it is precisely the "situation" that has been left behind in contemporary gigwork comedies. The diner waitress had coworkers; the Postmates deliverer does not. The taxi driver had a dispatch center; the Uber driver has an iPhone.

Unlike the post-crisis series of Szalay's account, these shows have no residual nostalgia for Fordism, largely because they do not feature baby boomer patriarchs like Tony Soprano, who can remember (and thus mourn the loss of) better days for white, male, waged workers in the US. They are instead both the product and the experience of what journalists term the "recession millennial" generation that has long recognized such promises as bankrupt. Millennials are poorer, more indebted, less likely to own a home, more likely to live with parents, less likely to have full-time work, less likely to have a job for which a college degree is required, and far more likely to work in low-paid service work or gigwork than the generation before them. For these workers, who labor outside even the minimal protections of the minimum wage, there are no binding forms of social or contractual obligation on offer. This means not only that we never see a boss and almost never see a manager, it also means there are far fewer conventional family relationships on these shows than there are on Taylor's work-family series or Szalay's domestic workplace dramas. Here, family ties are likely to look as they do on High Maintenance, where your ex-wife is cool with keeping you on her health insurance (or, on a later episode, where your parents let you use their HBO log-in) because, fuck, we all need health insurance. And we all need health insurance because neither our boss nor the state provides it. The dream of a restored social welfare system that Szalay finds in the 1980s domestic workplace drama now appears to be a quaint "artifact" of democratic "commercial broadcasting" that required no log-in.

To represent work in an epoch when worklife no longer follows a straight line, tipwork TV dispenses with the professional drama's character development. Whereas the sitcom or procedural's ability to disrupt and then restabilize working conditions by the end of each episode suggested a faith in a kind of contractual stability, the characters of tipwork TV are far more insecure. Formally, tipwork TV features episodic narrative structures and sketchier character arcs. As numerous critics have noted, these shows "grow together not from the pursuit of a single story but from the impulsive addition of ... a new connection, a new idea, or simply a new story" (Easy); and "privilege contiguity over continuity, accumulation over connection" (High Maintenance).57 They thus dispense with developmental narrative arcs in favor of "embrac[ing] the episodic" (Master of None), but in a radically different way than did the workplace sitcom. On the classic sitcom, the episode form mediated between the particularity of narrative incident and the generality of a predictable situation, such that any given episode could stand in for and exemplify the series as a whole. Tipwork TV — which favors episodic forms like the "bottle episode," where we are suddenly outside the standard world of the primary narrative and inside the experience of a minor character or unfamiliar space — instead tends toward "episodic dissonance" and becomes "pure sprawl" (Atlanta). Oriented toward the intimately particular and the fragment, and to an image of social life as mere contingent accumulation, tipwork TV also does not attempt the sweeping social realism that characterizes twenty-first century quality TV. The latter, Szalay contends, perpetually yearns to escape the confines of the domestic small-screen and to achieve more properly cinematic quality — to torque the continuity, coherence, and scope of melodrama and serial narrative and thus to push through economic stagnation and into dynamic historical time.58 By contrast, tipwork TV's non-continuous narrative time indicates little interest in historicity. Far from seeking to transform the small screen into the cinematic, it is the medium of the small-small screen, designed at least in part for the cell phones on which one might simultaneously access media "content" and be summoned by an app to pick up a rider.59

Yet while tipwork TV departs from the developmental plots of the professional drama of salaried work, from the repetitive stability of the working-class service work sitcom, and from the semi-filmic, serial realism of "quality TV" drama in the post-financial crisis era, it is not necessarily sui generis. Rather, these shows return to and reinvigorate a much older narrative form, producing what I will term in the next and final section a new mode of tipwork picaresque.

The Tipwork Picaresque

The term picaro — a figure Anne Cruz defines as "a lowly rogue living by his wits" — first appeared in a literary text in 1599 (in Mateo Aleman's Guzman de Alfarache).60 Although some critics date the origins of the picaresque genre as far back as the 1499 La Celestina, its codification in Spanish literature is typically dated to the mid-sixteenth century Lazarillo de Tormes; later influential examples in English include Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders and Roxana and Tobias Smollett's Roderick Random. Formally, the picaresque is an episodic narrative of only partially connected events depicting the adventures of a hero (or anti-hero) trying to survive under difficult social conditions. Often a criminal, the picaro is virtually always a "low class individual who yearns for a higher social status" and "tries his hand at several professions living by his or her wits."61 Although its commitment to realistic description make it an important precursor to the realist novel, the picaresque tends not to follow what Northrop Frye identified as the novel's "hence" structure (a causal and orderly organization of events) but rather to deploy the "and-then" narrative of the romance (where events follow on one another paratactically and in a potentially interchangeable order).62 Similarly, the picara doesn't develop as the classical realist protagonist does: rather, explains Edwin Muir, she is a "central figure" who, by being taken through "a succession of scenes," is used to "introduce a great number of characters, and thus build up a picture of society."63

Thus, Matthew Garret argues, the picaro is "not just a character; the picaro is a situation."64 This recalls, of course, my previous exploration of the situation in the sitcom, where the "situation" stood for the oscillation between episode and series, between destabilizing incident and stable routine, and between particular individual and general occupation — where situation, in short, was the situation of worklife in jobs that promise predictability at the cost of development or bildung. Yet the picaresque "situation" — in which Lazarillo can describe himself as the "servant of many masters" — has no such predictability. The idea of situation thus shifts from narrative predictability to its opposite, a paratactic string of destabilizing events and encounters without resolution. The picaro's relationship with his "many masters" takes the form of a series of heterogeneous "compacts" — effectively short-term work contracts wherein, as Ronald Paulson argues, "the master is responsible for his servant's education and welfare and the servant owes loyalty and duty to his master." Moreover, one or both of the parties typically ends up deviating even from the informal arrangement, and as a result the picaro is often paid too little to live on (or, sometimes, no wage at all).65 Because he must survive this kind of fundamental uncertainty, writes Stephen Miller, "there is no part the picaro will not play...He assumes whatever appearance the world forces on him, and ... definition and order disappear ... The picaro is every man he has to be, and therefore no man."66

In these accounts of the formal features of the picaresque (disorderly, episodic, paratactic) and of the character type of the picaro (protean, resilient, and, especially, a servant of many masters) we find deep resonances with tipwork TV. Influential shows like Atlanta, Easy, Master of None, and High Maintenance develop a genre I term "tipwork picaresque" to represent subjects whose working lives are defined by multiple and fragmented social relations and by temporary, uncertain, and fluid working conditions: characters whose stories are not so easily wrestled into more familiar narratives of development, education, and achievement. In this final section, then, I elaborate three key features of the picaresque that show up in contemporary representations of tipwork: an affective mood of pragmatic passivity; a tendency to connect service work and sex work; and, finally, an attempt to represent the dispersed — but still political — social relations that characterize what Michael Denning terms "wageless life."67

Garret's account of the picaresque aptly contrasts the "comical fool" to the picaro by saying "the picaro never moves; the picaro is moved."68 This differentiation between the manic, excessive fool and the more pragmatically passive picaro helps illuminate the affable but flat affect that permeates the tipwork picaresque. In her marvelous book Our Aesthetic Categories, Sianne Ngai argues that service work is most effectively represented by "zany" characters whose wild energy indicates the indistinction between work and play and whose bodily contortions reflect the demand that they be constantly "flexible" — think Jim Carey in The Cable Guy.69 We certainly see this form of zaniness in tipwork TV, especially on shows like Broad City and Kimmy Schmidt. Yet many contemporary tipwork picaresques focus instead on a much more muted way of being in the world — the pragmatic disconnection necessary to endure tipwork.70 The best example is High Maintenance: as the non-protagonist of an essentially plotless narrative of events, The Guy's namelessness indicates a refusal of conventional, developmental characterization. Instead, we have a character who is both Everyman (The Guy) and, as in Miller's description of the picaro, "every man he has to be," defined purely in anonymous non-relation to those he serves ("I'm gonna call The Guy"). Moreover, The Guy's (and, for the most part, High Maintenance's) affective mood features none of the zany's coked-up stimulation but instead a more passive stoner stoicism. In an early episode titled "Trixie," for instance, we meet a young couple who have recently moved to New York; they work in restaurants, but also make ends meet by renting a space in their tiny apartment on Airbnb. Exemplary "recession millennials," they become gigwork hoteliers and thus sacrifice sanity for a modicum of security: "We were gonna be adults this year, live by ourselves, and I don't know how else we're gonna pay the rent unless we do this."71 Stressed out, they call The Guy to deliver some weed, and invite him to sit in their cramped loft and smoke with them while they all talk about their jobs. "I'm never doing another service job again. Ever," The Guy says emphatically, only to correct himself in stoner trail-off, "Well I mean I guess this is a service job but ..."72 The Guy's disconnected geniality is nothing like Ngai's excessive zaniness, perhaps because like many service workers, he is a service worker who often serves other service workers. Here, in other words, his stoner "chill" seems a kind of gesture of solidarity towards his tipworking customers, who need no tip-soliciting performance.73 As Ulrich Wicks writes in his treatment of the picaresque, the picaro is "alternately both victim of that world and its exploiter" — here, then, what we have is less an indistinction between the activities of work and play as in Ngai's account, and more an indistinction between the character positions of server and served.74 Elsewhere in the episode, the passive pragmatism necessary to endure the fragmented experience of precarious labor under "many masters" is figured by the unnamed female customer of The Guy, who is of course also a tipworker herself.75 She describes waiting tables on a Sunday night and having a particularly bad day: "I'm bored, I'm alone, so I'm trying to engage them ... I bring them their enchiladas and they eat and then leave with their whopping eight percent tip. Then they leave, and I'm sittin' there, just, like, reading my Jane Austen novel, and then ten minutes later she comes back in ..." The story ends with the customer, who claims to know the waitress's father from West Virginia, making a rude sexual gesture at her while slamming the door. Here, we see the kind of emotional distance necessary to endure a certain kind of tipwork, a distance that has less to do with an incessant flow of activity and more to do with prolonged experiences of boredom punctuated by encounters whose survivability depends on separating oneself from the experience entirely.

As this story of a customer's rude sexual gesture toward a waitress also reminds us, the picaro was often a picara and a sexworker: George Starr, for instance, describes Defoe's Moll Flanders as a picaresque "criminal autobiography" through which Defoe was able to illuminate "the callousness of society towards the unprotected and the unproductive — orphans, debtors, criminals, single women without trades."76 While Starr emphasizes Defoe's use of the genre as a form of social critique, Cruz argues that although picaresques with male protagonists often sought to "criticize social attitudes towards the poor," stories of sexworking picaras saw sex work as a threat to the social order. The picaresque's scatological humor, she argues, allowed it to represent prostitution as a social contagion: the sexworker pollutes the social body, which in turn further contaminates the sexworker.77 Tipwork TV similarly tends to treat sex work as a metaphor for contagion or as a threat to a fragile and permeable masculinity, one unable to resist the perniciousness of a seemingly more intimate and embodied form of exploitation. Some characters describe their own experience of tipwork as abject by comparing it to prostitution, and others use the metaphor to feminize male service workers for receiving tips (which seem personal and thus make the recipient vulnerable) rather than wages. Pete from Crashing, after spending hours handing out fliers on the street for no pay (but a chance to perform at the club that night), first describes it as "butt-fuck" and then says, "I'm feeling kinda degraded. It's crushing my soul. I kinda feel like a prostitute." Likewise, in a Season 2 episode of High Maintenance, a customer aptly named "Johnny" taunts The Guy by asking, "You want me to leave the money on the counter like you're a hooker?" These comparisons between service work and prostitution emphasize the forms of alienation ostensibly specific to in-person service — especially the demand to appear to enjoy one's work — via the metaphor of being fucked for money.78 In so doing, they assume a manifestly heteronormative male perspective, implying not that prostitution is degrading because it is a form of service work, but that service work is degrading because it is a form of prostitution: a way of being fucked (and being paid) rather than being the one who fucks (and pays). This association is playfully reversed, in turn, in an episode from Season 4 of Broad City called "Just the Tips": flush with tip cash from her waitress job, Ilana goes on a tipping spree, flirtatiously stuffing all her cash in the back pockets and shirt collars of the male caterers and bartenders at a party. "Just the Tips" plays up (and, in Rabelesian style, overturns) the idea that bodily exposure or affective intimacy make tipwork uniquely abject. The metaphor of "the tip" is applied first to Ilana's French-tipped fingernails (she needs a mani-pedi because her feet have been grotesquely damaged by long shifts at the restaurant), which she uses to spear cheese cubes and snort coke. Later in the episode, "the tip" refers to the tip of her friend Jaime's penis, which he is considering circumcising to avoid recurrent yeast infections. Here, the link between tipwork and bodily pleasure is not a metaphor (à la service work as "butt fuck"), but rather a carnivalesque literalization.79

In fact, of course, sex work is less a metaphor for service work than simply a form of it: thus Maya Gonzalez and Cassandra Troyan's wonderfully provocative essay "<3 of a Heartless World" historicizes contemporary sex work "in relation to the demand for authenticity, intimacy, singularity and emotionality inherent to service economies and as an integral part of neoliberal capitalism's commodification of enjoyment and its corresponding extension of the working-day."80 This shows up on Easy's "Side Hustle" episode too: as I have already suggested, this episode, with its representation of Odinaka's three-shift life, is very much about the "extension of the working day." More to the point here, however, another story runs alongside Odinaka's: that of a sex worker and would-be essayist, Sally. The episode sets up a series of explicit parallels between their work, including a cross-cut between Odinaka scooping up the cash tips from his tourist-bus gig and Sally putting an envelope with the cash she's paid by a client on top of her refrigerator. Whereas High Maintenance and Crashing treat tipwork's metaphorical connection to sex work as a way to emphasize its degrading femininity, Easy seems forced to portray Odinaka's Uber driving in a resolutely (and not especially convincing) cheery tone precisely in order to avoid the implication that Sally's sex work is similarly exploitative. The show's salutary reluctance to abject sex work also requires it to celebrate gigwork — although there's no doubt that Sally earns better money.

The tipwork picaresque adopts not only the modes and moods of character common to the original picaresque, nor only its interest in the sexualization and feminization of service. Shows like High Maintenance and Easy also appropriate the picaresque's poetics, especially its use of the episodic "and-then" and its tendency towards formal diffuseness. The Guy's appearance in the diverse apartments of New York City gives High Maintenance its semblance of narrative coherence, but he might be central to one episode and in the next appear only briefly, at the door with a delivery; the other characters come and go, rarely returning from episode to episode. Even slightly more conventional shows like Atlanta and Broad City have dispensed with both the repetitive continuity of the sitcom (in which little changes) and the serial continuity of the drama (in which a lot changes, but via the novel's "hence" causality). Instead, in these series, things might change drastically or not at all from episode to episode; virtually no time might pass between two episodes and then a much longer, but still unmarked, span of time might intercede. Major changes in a character's life might happen off-screen and other characters might disappear entirely. Thus on Crashing, despite an otherwise conventional character arc, the broke and unemployed would-be comedian Pete spends each episode "crashing" with a different comedian, many of whom show up once and then never again. Easy takes this proliferation and discontinuity to an even further extreme, since its coherence is entirely spatial rather than temporal, with the Chicago setting doing all the work of providing what little continuity remains.

Shows like Crashing, Easy, and High Maintenance are thus structured around relationships that are both temporarily intimate and without real consequence, an inconsequentiality redoubled by the ephemerality of the episodes themselves, which introduce us to characters we will never meet again and which do so in a seemingly random way. Such encounters are definitive of the picaresque, which, Garret writes, is itself a "social relation," one in which brute necessity — the story of survival, of being "thrown from situation to situation, episode to episode, master to master" — becomes the contingency of social encounter.81 These social relations are also not so different from the kind an Uber driver might experience a dozen times in a single night: on the one hand, she will be rated via intimate and subjective measures like "Entertaining" or "Good Conversation" or "Cool Music"; on the other hand, the system for "matching" her with her riders (like the character system of Easy) is all about the pure algorithmic contingency of geographic proximity.82

So one might say, reasonably, that social life on tipwork TV resembles the experience of working for an app — or even the experience of using an app to hire someone else. But we might also say that this emphasis on social contingency, contiguity, and random accumulation resembles something else as well. Recall, for instance, Starr's description of Moll Flanders as a means for revealing the experiences of "orphans, debtors, criminals, single women without trades." Starr's use of the listing structure here cannot help but remind us of the additive and apparently random lists that so often show up in accounts of the class known as the lumpenproletariat, including Marx's famous description in The Eighteenth Brumaire of "vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaus, brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ-grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars" and Adam Smith's description of the unproductive class as "menial servants, ... churchmen, lawyers, physicians, men of letters; players, buffoons, musicians, opera-dancers, &c."83 Writing on the relationship between listing and the lumpenproletariat, Peter Stallybrass notes that in both its structure and its content, the wildly paratactic, juxtapositional quality of the list was a way for Marx and other nineteenth century thinkers to register "contradictory ways of seeing ... [the] multiplicity" of the lumpen.84 The lumpen, we might say, appear as a list because it is a population, which merely accumulates randomly and heterogeneously ("&c."), rather than a class, which develops and coheres around shared interests.

If the list is the rhetorical form for the lumpenproletariat, the picaresque is its genre. This is true not only because the "rogue" of the picaresque is also likely a member of the "shabby class" of the lumpenproletariat, but also because the picaresque's preference for the episodic over the continuous, parataxis over bildung, dispersal over development, and — in contemporary tipwork picaresques at least — fleeting spatial encounter over extended historical association makes it an apt form for describing the experiences of a population defined by exclusion, precarity, and superfluity rather than by any more stable, homogeneous, predictable coherence.

The lumpenproletarian and the picara also share a removal from the wage. Cruz, for instance, explains that because the picara is often unemployed, her poverty is not signaled by her labor exploitation (a category more meaningful within a more fully developed wage system), but rather by her inability to buy the basic goods of survival: "when bread doubled in price, people starved."85 I have already suggested that neither premodern nor contemporary picaresques depend on the coordinates of character as arc or bildung that attend narratives of professional development under the salary or wage. Cruz's account helps us see not only that the picaresque is not a genre of the wage, but also that it is the genre of unwaged work, of tipped work, and perhaps especially of prices, what Joshua Clover has influentially identified as the "the measure of the marketplace" (as compared to the wage as a measure of classically productive work). The gigworker, the tipworker, and the picaro all confront the "old problem of consumption without direct access to the wage," as Clover puts it.86

As this suggests, lumpenproletariat is an old term with new relevance as well as new names: what the Endnotes collective terms a "surplus population," what Denning calls "wageless life," what Clover describes as the "excluded and indebted."87 Contemporary capital accumulation has clearly come to produce more, not fewer, of those whom Starr (writing on the eighteenth century picaresque) calls "unprotected and unproductive" and Denning (writing on contemporary underemployment) describes as "'wage hunters and gatherers', casual labourers and service providers who work for others in the intricate disguises of contracted and piece-rate jobs."88 As my earlier account of the shift from manufacturing to services suggested, an ever-growing portion of the population is today employed in service jobs, tipwork, and gigwork with wages so low they aren't even worth automating into superfluity.89

The additive, discontinuous list structure that describes the lumpenproletariat — "brothel keepers, porters, literati"; "players, buffoons, musicians" — is formalized on shows like Easy and High Maintenance via a poetics of circulation and contingency and an insistence on foregrounding the accumulation of incidents rather than the coherent development of an individual character or narrative. At the level of content, moreover, tipworkers, gigworkers, and the diffuse lumpenproletariat also make up the character class of the tipwork picaresque. Thus to the lists above we might add another: doorman, bodega cashier, taxi driver. These are the three kinds of service employment that show up on the final example of a tipwork picaresque I will discuss here, namely the "New York, I Love You" episode of Netflix's Master of None. Generally, Master of None is a somewhat conventional bildungsroman, though it is clearly informed by the episodic tendencies of contemporary TV described above. Season 2's "New York, I Love You," however, departs from the show's predominant plotlines and from protagonist Dev. It begins with Dev and his friends discussing a movie they want to see, but quickly moves away from them and instead follows different characters who shift abruptly from the scene's background into its foreground: Eddie, a doorman; Maya, a bodega cashier; and Samuel, a taxi driver. The arc of the episode follows a kind of associative logic that rhymes with the protean restlessness of the picara, with the contingent contiguity of social life under non-waged work, and with the spatial logics of Clover's account of circulation as the dominant logic of capital accumulation in a post-industrial age: Dev passes Eddie on the street, we leave Eddie behind when he passes by Maya's bodega, and Maya is second in line for Samuel's cab. In the most powerful sequence about the relationship of these minor characters to the economy of the city — and to the economy of plot — Eddie is yelled at by a resident in the building who has brought a woman upstairs and charged Eddie with warning him if his wife is coming. When Eddie isn't able to do so, the man yells "You have one job to do. One!" to which Eddie replies, "Actually sir, I have many different jobs for many different people." Eddie, in other words, is the "Master of None" referred to by the series' title: not only because he is a "jack of all trades" and not only because he is a master of no one, but also because his own masters are not one but many. As the seventeenth century Spanish picaresque The Rogue described its non-protagonist, he "is all the World: know him alone/And then yee know a Multitude in One" — for the picaro, nothing is more constant than inconstancy, and yet in both his pragmatic struggle for survival and in his multiplicity, the picaro represents a threat to the social order, insfoar as he is protean, canny, and increasingly typical.90

The wage implied a relatively clear and stable social relation — and thus also made clear the antagonism — between bosses and employees. Such stability and clarity are not always available to tipworkers and gigworkers, as when the bartender calls an Uber to get to work, or the Postmates deliverer stops for a drink on her way home. Yet this confusion also opens up new sites and forms for solidarity and political belonging at the points of consumption and circulation, producing what I earlier described as a kind of moral economy among the tipworking class. By Thompson's account, tips might represent a "definite, and passionately held, notion of the common weal." This moral economy is by no means apolitical — rather, Thompson insists that such "popular resentment" could become profoundly political when a seemingly disorganized crowd is met with "an outrage to these moral assumptions."91 Thus, what Thompson terms "the market place" — the places where workers eat together or at home, the means by which they get to work or come home, the places they drink or the way they get a heavy piece of furniture moved — have the potential to become "as much an arena of class war as the factory and mine became in the industrial revolution."92 "New York I Love You" aptly ends with a modest, but remarkably powerful, image of marketplace mutual aid among the marginally employed. One of Samuel's friends, who works at a fast-food restaurant, opens up the restaurant after hours and gives free food to Samuel and a group of randomly met acquaintances he is out hanging out with. In the closed restaurant on a darkened street, they drink and dance on the tables.

For Thompson, the ultimate expression of this "popular resentment" is the food riot. For Clover, likewise, the riot — which might itself attract a heterogeneous and contingently accumulated mass of the exploited, the underemployed, the unemployed, the criminalized, &c. — is the political form most adequate to a moment once again defined by "the old problem of consumption without the wage." Here we might recall that when the nobility attempted to ban the practice of giving vails to servants in Scotland, the servants did not strike but rather rioted: as one contemporary account had it, "the coachmen, footmen, &c ... created a great disturbance at Ranelagh-house ... They began by hissing their masters, then they broke all the lamps and outside windows with stones and afterwards ... pelted the company ... with brick-bats."93 We might also note that after the death of Avedano, the Caviar deliverer killed when he went out in a storm lured by the promise of surge pricing bumps, masked activists in San Francisco blocked the street to create a memorial to him, preventing tech company commuter buses from making their morning rush hour journeys, graffitiing busses and buildings, and destroying a pile of the app-based scooters currently a scourge of life in "techsploitation" cities like SF. There are, admittedly, no equivalent riots — at least not yet — on tipwork TV, and we will likely be disappointed if we wait for them to show up there. Better, perhaps, to hope of tipwork TV that it might represent wageless life without recurring to fantasies of how great things were under the wage. It is hard to tell the story of tipworkification, precaritization, and the production of an underemployed lumpenproletariat without seeming to imply that being forced to rely on a wage for one's survival constitutes stability or security. Indeed — as I know because this essay itself has struggled to do it — it is hard even to make clear that minimum wage laws have historically failed to protect most workers, let alone all of them; or to remember that service workers who do not rely on tips to earn their minimum wage still mostly do not earn anything close to a living wage.94 To the extent that a popular consensus among tipworkers — a popular consensus that might well show up in popular culture — does more than just advocate for a return to the false promises of the wage contract, it might have to leave behind the contractual dystopianism not only of "subminimums" but also of "minimums," asserting a right to more than mere subsistence and moving us to demand the richer maximums that we and others require.

Annie McClanahan is an Associate Professor of English at the University of California-Irvine. She is the author of Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and 21st Century Culture (Stanford, 2016) and is currently working on a project tracking the cultural and intellectual history of microeconomics.

References

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer and to Sean McCann for their useful, incisive feedback on this essay. Thanks too to Arthur Wang for his editorial assistance and labor. The idea for this essay was first sparked by a conversation — and later conference panel — with Jasper Bernes, whose insights about contemporary work have been crucially important to me. A special thanks, finally, to Michael Szalay, who has been a generous reader of this essay and whose argument about contemporary TV and the family wage has been immensely important to my thinking.

- It also seems like the opposite of artisanal labor shows like Top Chef and Project Runway.[⤒]

- Michael Tueth, Laughter in the Living Room: Television Comedy and the American Home Audience (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2005), 118.[⤒]

- Ella Taylor, Prime-Time Families: Television Culture in Postwar America (Berkeley: University of CA Press, 1989), 111, 14.[⤒]

- Tueth, Laughter in the Living Room, 120.[⤒]

- Ibid., 124.[⤒]

- Richard Butsch, "Class and Gender in Four Decades of Situation Comedy: Plus ça change..." Critical Studies in Mass Communication 9.4 (1992): 387-399, 389.[⤒]

- See Lynne Spangler, "Class on Television: Stuck in The Middle," The Journal of Popular Culture 47.3 (2014): 470-488.[⤒]

- Tueth, Laughter in the Living Room, 134.[⤒]

- In 1950, manufacturing represented 33% of the US economy while services represented 24%; today, manufacturing is only 13% while services are 50%. Drew Desilver, "Most American Unaware That as US Manufacturing Jobs Have Disappeared, Output Has Grown," Pew Research Center (July 25, 2017); Robert Scott, "The Manufacturing Footprint and the Importance of US Manufacturing Jobs," Briefing Paper 388, Economic Policy Institute (January 22, 2015).[⤒]

- Matthew Klein, "The Great American Make-work Programme," FTAlphaville, September 8, 2016. There are many structural reasons that service work has come to dominate US employment, one of which is that jobs in in-person service are much less likely than jobs in other sectors to be automated out of existence. In manufacturing, the long-term tendency is for workforce size to decrease (in a given industry) because labor can almost always be made more productive. This is not true, however, of service work. Westworld's fantasy of robot bartenders (robots designed, aptly enough, by a man with the last name Ford) notwithstanding, low-paid service work of this sort is in fact subject to a paradox when it comes to automation: while a recent McKinsey study suggests that 73 percent of the activities workers perform in food service and accommodations have the technical potential for automation, it makes no sense to create an expensive robot to do what a human will do for minimum wage (or less). Michael Chui, James Manyika, and Mehdi Miremedi, "Where Machines Could Replace Humans — and Where They Can't (Yet)," McKinsey Quarterly (July 2016). [⤒]

- Quotes from and references to Szalay's work throughout this article refer most directly to his essay "Melodrama and Narrative Stagnation in Quality TV" forthcoming in Theory & Event but part of a larger book project. Unpaginated MS, quoted with permission.[⤒]

- Sylvia Allegretto and Kai Filion, "Waiting for Change: The $2.13 Federal Subminimum Wage," Briefing Paper 297, Economic Policy Institute, February 23, 2011.[⤒]

- Sylvia Allegretto and David Cooper, "Twenty-Three Years and Still Waiting for Change: Why it's Time to Give Tipped Workers the Minimum Wage," Briefing Paper 379, Economic Policy Institute (July 10, 2014).[⤒]