Web 2.0 and Literary Criticism

The most widely read poets today share their work on Instagram, where they reach huge audiences. Rupi Kaur, perhaps the most famous Insta-poet, has 3.6 million followers as I write this. A masked bard who calls himself Atticus has 1.1 million.1 Cleo Wade has 509,000; Tyler Knott Gregson, 359,000. These are enormous numbers for poets. By way of comparison, Timothy Yu reports that in 2017, the best-selling poetry book from a traditional publisher was Mary Oliver's Devotions, which sold 36,000 copies. That year, Kaur sold 1 million copies of her book, Milk and Honey, a mere appendage to her primary outlet on Instagram.

Despite their popularity, the Insta-poets have come in for a fair bit of derision. Their work is full of clichés so cloying your teeth will ache. I first heard of Insta-poetry from a student, who mentioned it quite sheepishly. A few months later, at a bookstore in Washington, DC, I overheard two teenage girls as they stood beside a high stack of Kaur's books. One asked the other what she thought of Kaur, to which the second replied, "I kind of think she's, like, 'fake deep,' you know? But I'm sort of a poetry snob." As a professional poetry snob, I confess that my heart leapt at the verdict.

In what follows, I'll nonetheless try to learn something from the Insta-poets, something about the technological scene of contemporary poetry, without advancing a judgment about their work. The complex intersections of Insta-poetry's political, commercial, and literary significance have frustrated literary critics' efforts to evaluate it. So for now, I want to suspend questions of value in order to ask how Instagram structures poetic forms and participatory reading practices.

Because Instagram emphasizes pictures over text, the platform gives readers new ways to encounter old lyrical modes. Poems on Instagram get shared, viewed, and saved as images, rather than text files, so their visual presentation matters. But instead of exploring the innovative textual styles that computers make possible, such as animated text or unusual fonts, most Insta-poets deploy nostalgic visual tokens of literary refinement. They write in ornate scripts, use old manual typewriters, present their work on richly textured paper, or include little illustrations. Such techniques ironically use Instagram to reassert the traditional notion that genuine poetic expression looks inky and papery — that a poet's work appears most authentic not on an ephemeral, impersonal screen but on the scribbly, insistently material paper she has physically inscribed. The fact that the visual rhetoric of ink and paper now arrives to us through smartphone screens should indicate how deeply such rhetoric continues to inform our reading habits.

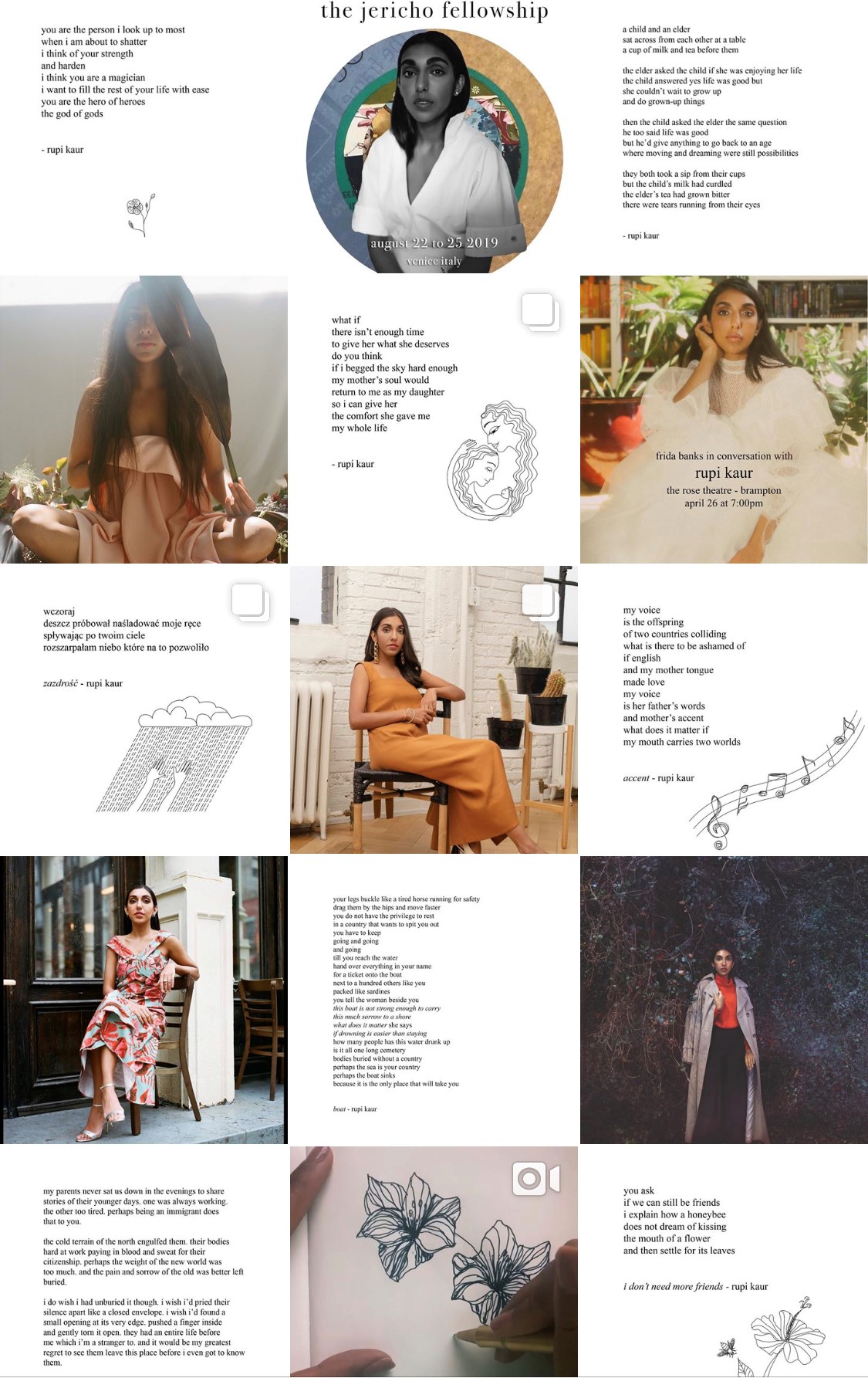

One might expect poets, given their interest in words, to prefer a social network that permits text-based posts, as Twitter and Facebook do.2 Instagram requires every post to be a picture or video. The Insta-poets' counterintuitive choice of venue equips them to conjure feelings of intimacy with their many followers. Instagram encourages a visual rhetoric of personal authenticity. The most popular Insta-poets intersperse their poetry with conventional Instagram fodder: selfies, artsy nature shots, exotic travel pictures. Through the distanced intimacy of a social network, these images help us see the Insta-poets as authentic people. At the same time, these nonliterary posts can seem like confections of personality, too tidy to feel authentic. Tyler Knott Gregson, for instance, follows a predictable cycle: he posts a handwritten haiku, followed by a typewritten poem, followed by a color photograph (usually a nature shot), then another handwritten haiku, and so on. The cycle repeats once daily. Only about once a year does an out-of-sequence post disrupt this pattern. Rupi Kaur is still more repetitive: she alternates between color photos, mostly of herself in designer clothing, and black-and-white pictures of her poetry, usually adorned with a hand-drawn sketch. This binary pattern reaches back, without a single exception, for at least the past five years. (See Figure 1) The regularity is offputtingly mechanical. The pictures of Kaur might give her account a more personal feel if the unwavering alternation between photos and poems were not so formulaic. Other regularities make Kaur's feed seem even more robotic. As I write this, all of her ten most recent posts, which span almost a month, were posted between 11:30pm and 2:45am UTC. What does Kaur know about this timeframe, and how?

To note such regularities might seem like a kind of distant reading, since it does not involve close textual interpretation, but these observations emerge from the individual user's experience on Instagram. Upon discovering a new account, it is easy for a user to notice general patterns, such as the size of its audience or the type and variety of posts it offers, before looking more closely at individual posts. More active accounts appear in one's feed more frequently. Observations like these do not fit tidily into methodological designations such as close/distant or qualitative/quantitative. Hence, new technologies can help us to reconsider our interpretive methods, not least by returning our attention to the embodied phenomenality of reading, the physicality of textual interfaces.

You might think literature published online should lend itself to computational analysis. Indeed, bulk textual analysis of the many comments on each Insta-poetry post might reveal what modes of participatory readership these poems tends to garner.3 But the Insta-poets frequently deploy visual effects that underscore our embodied interfaces with reading and writing equipment. Neither traditional hermeneutics nor computational analysis can adequately unpack these effects. Instagram poetry instead calls for a reading practice that distances itself from individual texts enough to note these structural effects of the platform, while also remaining attuned to how these effects register visually for individual readers.

In the remainder of this essay, therefore, I focus on a visual element of Instagram poetry that substantially contributes to its expressive powers, while eluding familiar methods of computational analysis. That element is handwriting. The Instagram poets join a long tradition that views handwriting as heightening the lyrical intensities of a poem, its status as an intimate, affectively rich expression of the poet's thoughts and feelings. Because Insta-poems live online, not in books or paper archives, these works underscore how handwriting challenges familiar methods of computational literary studies.

My engagement with handwriting in Instagram poetry is part of a longer project that explores the poetics of handwriting since the emergence of the typewriter. This project responds to the treatment of handwriting in existing accounts of modern poetic form and in influential histories of the book. Both of these discourses subordinate handwritten script to type and especially to the typewriter, that mechanistic avatar of modernity. A hermeneutic of typewriter formalism predominates in accounts of poetic sound and shape since the first decades of the twentieth century.4 The word processor's similarities to the typewriter perpetuate this consensus; the earlier technology continues to influence how we think about poetic form.5 Book historians, meanwhile, have challenged the assumption that manuscript historically and conceptually precedes print. Jonathan Senchyne asks, "Is it possible to think up such a thing as a 'manuscript,' a text defined by its handwritten production, before the spread of printing in Europe?"6 Only in the era of print, after all, can we imagine handwriting as prior to something; one needs the idea of print in order to view handwriting as the originary site of written expression. Historically, printing has not replaced handwriting but solicited more of it — the filling-out of forms and the marking-up of other printed matter.7 In response to these accounts, I argue that handwriting maintains a marginal but decisive presence in the twentieth-century development of poetic forms. Furthermore, if the book historians show that print conceptually precedes manuscript, then what we see now is manuscript coming after the era of print — handwriting and not e-text as the privileged visual form of post-print authorship.

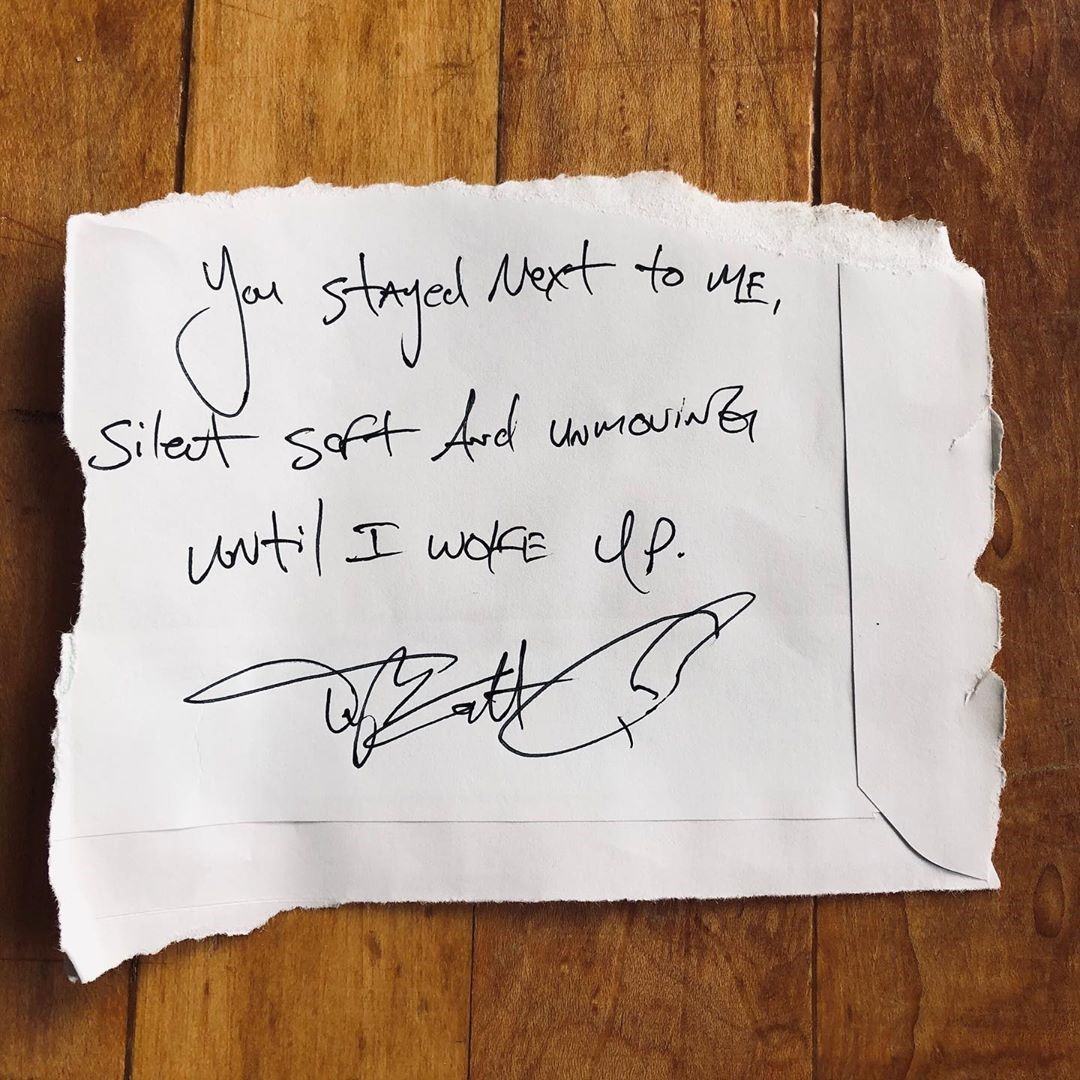

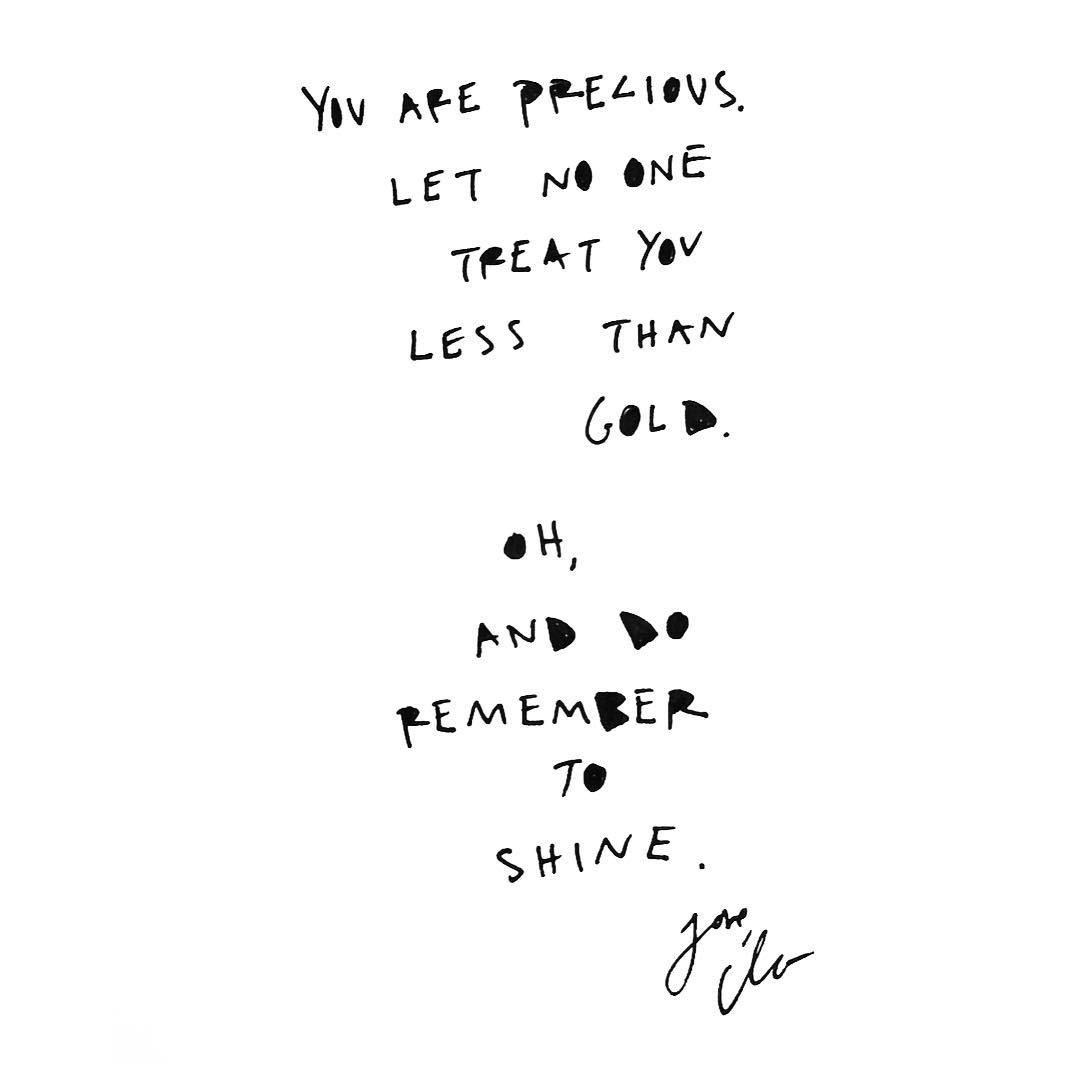

Many Insta-poems either appear handwritten or bear some handwritten embellishment, like a signature or illustration. The Insta-poets who foreground their handwriting develop extremely consistent, distinctive styles, which lend their work visual cohesiveness. Each of Gregson's aforementioned haikus, for example, is written in the same dramatically looping script. (See Figure 2) The haikus do not simply cluster around the sign "Gregson" but around his style of inscription. Handwriting thus functions as a stylistics of authorship; it underscores the physicality of the specific body writing.8 Wade employs an even more idiosyncratic handwritten style, though to much the same effect. She writes in all-caps and fills in the hollows that typographers call enclosed counters — the triangle in the uppercase A, for instance. (See Figure 3) She signs most of her poems "Love, Cleo," using a more conventional script for this touch. Sometimes she omits the comma, insinuating the imperative. Because Wade uses her distinctive block capitals not only for poems but also for advertisements, political statements, and other posts, it becomes difficult to distinguish her literary production from other types of writing. Just as Susan Howe said of that quintessential poet of handwriting, Emily Dickinson, that her "poems will be called letters and letters will be called poems," so do Wade's posts cohere around the handwriting itself as much as any axis of generic unity.9 The remarkably consistent, idiosyncratic appearance of the poet's handwriting invokes the specific hand that produced it.

Given the regularity of their handwritten styles, one might suspect that Wade and Gregson use some kind of graphics software to produce their work. One of my students even suggested that Gregson uses software to simulate different stationeries. I emailed both poets to ask about their equipment. Wade did not respond, but Gregson gave a helpful explanation. "Never once has anything been simulated," he assured me, "it's all old school." He writes the haiku with Pilot G-2 rollerball pens "on random scraps of paper that find their way into my life," and he shoots them with his iPhone, despite the fact that he is a wedding photographer.10 His typewritten poems come from a Remington or Olivetti manual typewriter and go into a high-definition scanner. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Gregson's peers likewise work on paper instead of graphics tablets: some pictures of Kaur show her holding a pen, and some of Wade's posts include textural imperfections that attest to genuine paper — or else to a good simulation. In the end, however, their actual compositional equipment matters less than the evocative powers of the images they produce. Even if they used software or even robotics to simulate genuine handwriting (as I have done), the appearance of handwriting on Instagram powerfully shapes their readers' experiences.

Much of handwriting's allure stems from its status as a material trace of the embodied poet's physical gestures on the page. This auratic power of handwriting persists even across the tricky distances of social networks and smartphone screens. Its endurance suggests that the electrification of literary consumption has entrenched, not displaced, the traditional figures through which readers construct a poet's expressive authenticity — including the figure of their handwriting. Even in digital reading environments, the stylistics of handwriting inform what rhetorical and technological avenues most powerfully invoke the presence of an author. For fans of Instagram poetry, the image of a poet's handwriting might stir feelings of closer personal contact with them. If it does, this reading habit perpetuates an old and familiar graphological imaginary, one that informs the significance of handwriting in a wide range of reading communities today.

This graphological imaginary views handwriting as a vehicle of affectively intense, personally authentic expression. It is a discernably lyrical attitude. The lyrical theory of graphology holds that a writer's personal identity registers on paper, in the trace of the writing hand. This attitude prevails in a range of fields today, from forensic document examination to fortune telling to literary manuscript criticism. It differs from the graphological imaginary that organizes paleography, for example, and cursive pedagogy. These latter formalize the geometry of handwriting in a nonpersonal way; they make normative statements about the shapes handwriting can or should take. The lyrical approach to graphology holds that each person's handwriting is idiosyncratic enough to reveal who wrote a given manuscript. This notion did not become common in the anglophone world until the nineteenth century.11 A corollary of the lyrical attitude holds that a person's handwriting reveals other details as well — their personality, age, gender, health, or mood at the time of writing. Most claims of this sort now seem like quackery even to the most speculative critics, but given the studied idiosyncrasies of the Insta-poets' handwriting, the writers might embrace the idea that their handwriting conveys not only their personal presence but also their personality or emotions.

Though the reading habits that privilege handwriting are old, the technologies that make it visible are new. Thanks to the internet and digital photography, it has never been easier to see a poet's handwriting. Whether you're interested in Dickinson or Rossetti or Whitman or Moore, large online archives now provide astonishingly detailed views of their manuscripts. The technologies that promised to deliver us from pen and paper have instead redirected attention to the handwriting of poets old and new. When people see Dickinson's handwriting or Gregson's, they usually view it through the very electronic media that seemed to inaugurate a post-paper, post-handwriting textual ecology. Even on a screen, the poet's handwriting still invokes the physicality of paper. The sidelining of stylus-based textual production in most scenes of writing today helps to make handwriting more visible as a sign of the author's presence.

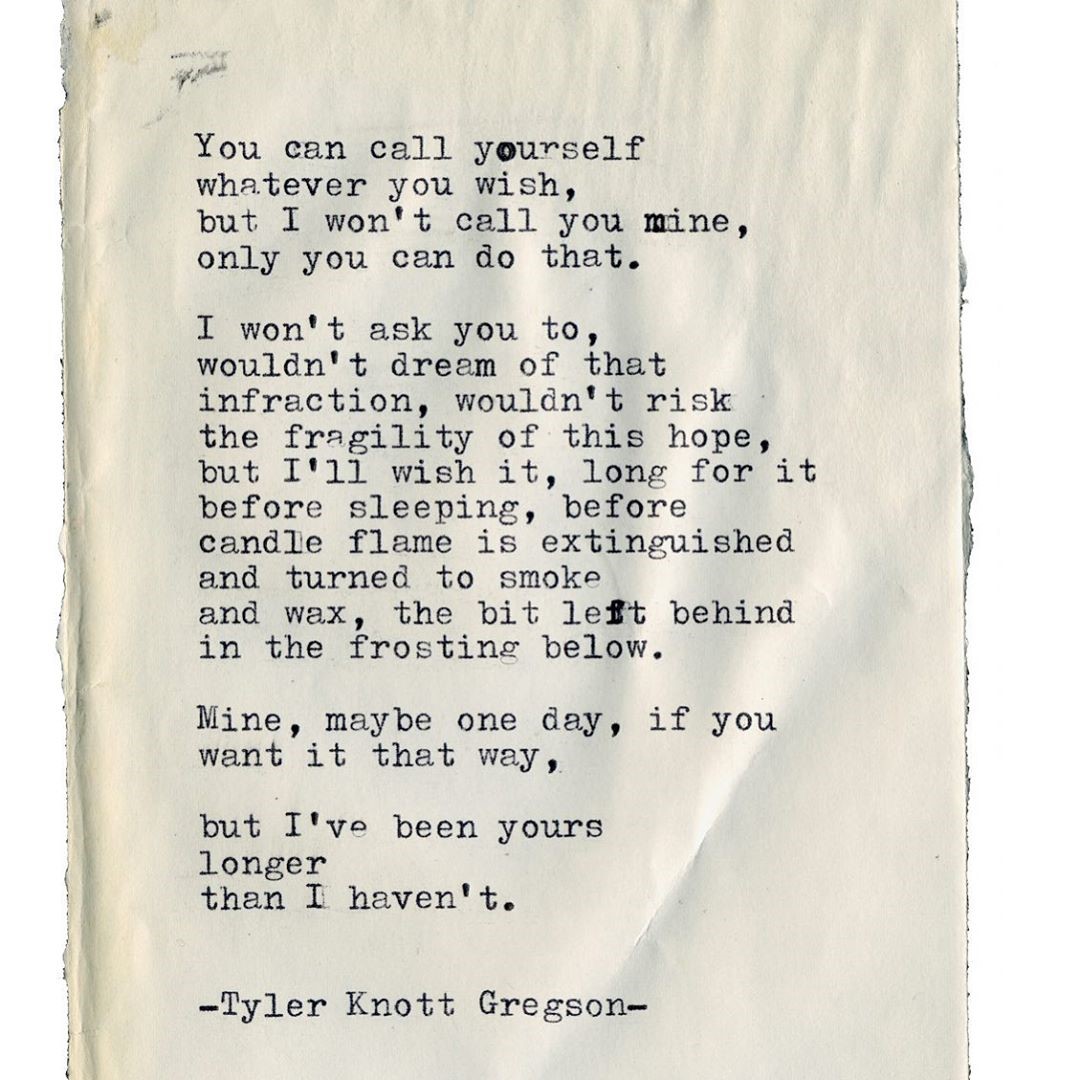

The handwriting of each Insta-poet might appear distinctive, but it is also remarkably consistent. From one poem to the next, Gregson's looping script and Wade's playful capitals look so regularized as to seem mechanically produced. This regularity diminishes the auratic powers of their handwritten work, making it seem formulaic instead of bearing a personal touch. Even when they seem robotically produced, the handwritten Insta-poems still invoke nostalgia for obsolescent writing equipment, for technologies whose literary cachet increases with their datedness. For the same reason, some Insta-poets also display poems written on manual typewriters. (See Figure 4) When such obsolete textual equipment invokes literariness on digital platforms, we might link this effect with the iconography of what Jessica Pressman calls "bookishness." Despite the enduring aura of handwriting on Instagram, its regularity might also align the Insta-poets with the more normatively inclined graphologies mentioned earlier, such as those of paleographers or handwriting instructors. A more thorough survey of handwritten poetry on Instagram could reveal the emergent norms to which their work corresponds.

Even if the consistency of handwritten styles in Insta-poetry makes the script look mechanically produced, this regularity does not make the handwriting easier to analyze. Indeed, the highly qualitative, impressionistic effects of handwriting make it a tricky object for scholarly interpretation, including the familiar kinds of computational literary analysis. Computers make it dramatically easier to see a poet's handwriting, but the devices that so brilliantly display manuscript images offer surprisingly few ways to interpret them. Even as computational analysis of e-text becomes common among literary critics, manuscript images remain largely inert in digital environments. Scholars have used software for bulk analysis of visual artifacts such as book covers, animated films, oil paintings, and magazine covers, but these tools cannot do much with manuscript images. Emerging software for handwriting recognition remains unreliable — and totally incapable of detecting the subtle, qualitative nuances that humans perceive in a poet's handwriting. It remains to be seen whether a quantitative, computational model of such nuances will become possible.

In the meantime, scholars interested in the lyrical effects of handwriting, whether in Instagram poetry or elsewhere, face three interrelated challenges. First, we must clarify our assumptions about the kinds of information that handwriting encodes before we can develop more effective tools for computational manuscript analysis, whether through handwriting recognition or some other means. Second, in the process of learning from the limitations of existing methods for handwriting analysis, we might develop a sense of other analytic blindspots that the current digital-humanities toolkit leaves unaddressed. And third, whatever the capabilities of present and future technologies, we should continue to question the reading habits that give handwriting its special allure in the first place. Such measures will help to explain not only the appeal of Instagram poetry but also the metaphysics of authorial presence that structures our approaches to more canonical authors.

Seth Perlow is an associate teaching professor of English at Georgetown University. He wrote The Poem Electric: Technology and the American Lyric (Minnesota, 2018) and is now working on a book about handwriting and electronics.

Keywords: social network, literariness, handwriting, personality, form

References

- I did not coin Insta-poet and Insta-poetry, terms the poets do not use, but the prefix nicely conveys the perfunctory, ephemeral qualities of the platform.[⤒]

- As Christian Howard notes, Twitter does host participatory cultures interested in poetry and other literature, including those who post under #poetrycommunity and related hashtags, but few poetry accounts on Twitter attract audiences even one-tenth the size of those on Instagram.[⤒]

- Popular tools for computational text analysis include MALLET, Voyant, and the Natural Language Toolkit for Python.[⤒]

- The typewriter becomes especially important for thinking about poetic form after Charles Olson's discussion of it in "Projective Verse," which not only influenced experimental poetry after 1950 but also provided a new approach to form in Olson's modernist precursors. In his influential Black Riders, Jerome McGann reads even Emily Dickinson's manuscripts in terms of Olson's ideas about "composition by field," thereby interpreting nineteenth-century handwriting through a twentieth-century theory of type (27). McGann's is not the only notable account of technology and poetic form to emphasize print and typewriters over handwriting. Cf. Jerome McGann, Black Riders: The Visible Language of Modernism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993); Marjorie Perloff, Radical Artifice: Writing Poetry in the Age of Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).[⤒]

- As Matthew Kirschenbaum acknowledges in his literary history of word processing, "there is a basic visual continuity between a personal computer and a typewriter." Kirschenbaum brings to this analogy more nuance and skepticism than it often enjoys. Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 20.[⤒]

- Jonathan Senchyne, "Print Culture," in Henry David Thoreau in Context, ed. James S. Finley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 112.[⤒]

- Cf. Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014) and Peter Stallybrass, "Printing and the Manuscript Revolution," in Explorations in Communication and History, ed. Barbie Zelizer (New York: Routledge, 2008), 111-118.[⤒]

- Meredith L. McGill has explored the linkages among signature, literary authorship, and style in Edgar Allan Poe's essays on autography. Cf. Meredith L. McGill, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834-1853 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 176-86.[⤒]

- Susan Howe, "These Flames and Generosities of the Heart: Emily Dickinson and the Illogic of Sumptuary Values," in The Birth-mark: Unsettling the Wilderness in American Literary History (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), 140.[⤒]

- Tyler Knott Gregson, "Re: question about your techniques," e-mail to the author, June 13, 2019.[⤒]

- Multiple factors contributed to this shift: higher literacy among the growing bourgeoisie made handwriting less a marker of social position; romantic individualisms emerged in response to industrialization; and later in the century, the typewriter offered an impersonal way to write, by contrast with script. For a history of handwriting in this period, see Tamara Plakins Thornton, Handwriting in America: A Cultural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).[⤒]