Web 2.0 and Literary Criticism

Given the rise of post-press literature and the continued creation of literary works in what Simone Murray has called the "digital literary sphere," our seminar "explore[d] the transformative effects of information technologies on the making of contemporary literature and literary culture in a global context."1 Scholars such as N. Katherine Hayles, Espen Aarseth, and Marie-Laure Ryan have long been examining the literary changes taking place in this sphere, and they analyze these changes from narrative, material, and aesthetic perspectives.2 Yet more than just altering aesthetic and material conditions, digital spaces are increasingly used as publishing platforms that are not determined by the traditional economic, national, or linguistic boundaries that govern the print-bound publishing industry. Rather, these digital spaces facilitate the development of a transnational and multilingual audience that is defined not by nation but by particular online communities. We're at a turning point in literary studies, and we need to confront how the changes in mode are affecting — and have been affected by — the alternative networks of circulation within these digital spaces.

Twitter literature exposes the particular changes that the web 2.0 digital literary sphere bears upon concepts of authorship and audience. Most of the academic discourse surrounding Twitter literature has focused on the work of professional writers who have already established their literary reputations (often within traditional, print-based publication circles), including figures such as David Mitchell, Jennifer Egan, and Teju Cole.3 But these well-known writers used Twitter as an experimental publication platform in the early to mid-2010s, after which they lost interest in this form of writing. As a result, critics such as Simone Murray have asserted that Twitter's popularity as a publication platform has already come and gone.4 But in marked contrast to the use of Twitter by established authors, a growing community of amateur writers has been using Twitter to publish their poems, stories, and other shortened forms of writing. This literature is similar to the Instagram poetry discussed by Seth Perlow, but it also differs from it in several important ways, including Twitter's priority of text over image, its character limits, and the use of hashtags as a primary organizing feature of the amateur Twitter writing community.

The amateur writing community on Twitter, which is comprised of a transitory and shifting group of global writers and readers, is developing a literary form that is self-identified by its creators through the use of hashtags related to literary genre. While this literature may not align with literary forms defined by the academic community, the amateur writing community on Twitter is nonetheless creating a global network of literary output on a hitherto unprecedented scale, and the literature produced by this community is worth being preserved and studied by literary scholars.

The development of the amateur writing community on Twitter is facilitated by the conditions of the platform itself, which has created a new kind of paratext that reframes the definition of the literary. This reframing occurs through the use of hashtags, and amateur writing communities on Twitter employ hashtags as a means of signifying literary form or genre (e.g., #haiku or #veryshortstory).5 For instance, Joe Pagano posted a tweet tagged with #poem, and SHSK English posted another tagged with #veryshortstory. These tweets are similar in form and even in content, but the particular genre to which they belong (poem vs short story) is distinguished by the hashtag chosen by the writer. Sometimes these genre hashtags reveal specific features about the literary work itself, and certain hashtags (such as #scifi or #queerfiction) can provide otherwise unknown contexts to the literary work. So more than just serving paratextual purposes, these hashtags also help us interpret the content of the tweet.

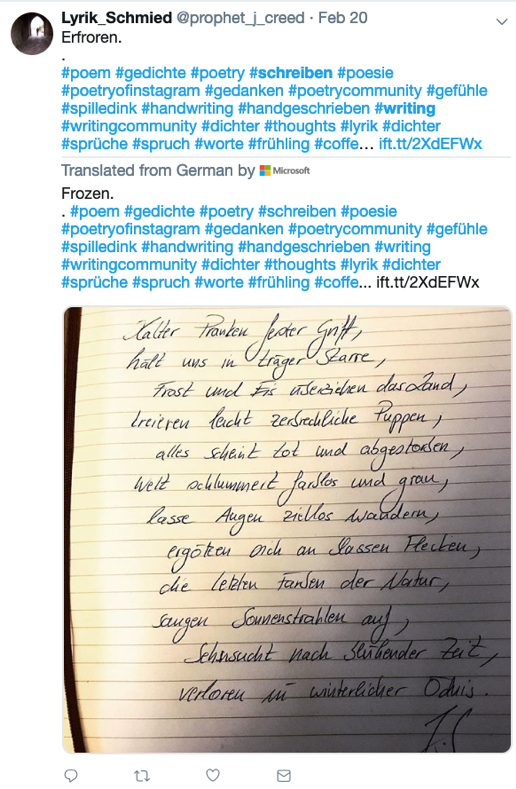

The hashtags that help define works of Twitter literature are instrumental in promoting the transnational and multilingual circulation of this body of writing. Since there are no standard hashtag terms or limits on what words can be made into hashtag groups, there are dozens of hashtags that signal writing communities. Given this decentralized nature, the Twitter writing community often tags its literary tweets with multiple hashtags in order to garner a larger audience of readers. This tagging occurs across linguistic groups, and amateur Twitter writers use multiple hashtags to distribute their work. For instance, a German poet with the Twitter user name "Lyrik_Schmied" has used the affordances of Twitter to disseminate the poem "Erfroren" to both English and German writing communities through hashtags. The poem itself is in German, but the poet has used a combination of English and German (almost in equal number) writing-related hashtags to promote the poem. These hashtags include #poetry and its counterpart, #gedichte; #writing and #schreiben; #poetry and #poesie; #thoughts and #gedanken; and #handwriting and #handgeschrieben. Literary hashtags on Twitter are used not only as a means of self-identifying a literary tweet, but also as a means of self-promotion and inter-linguistic exchange.

The multilingual and transnational work done by amateur writers on Twitter is augmented by several initiatives undertaken by Twitter itself, which participates in the larger economy of the digital literary sphere by marketing itself as border-crossing. There are three primary forms of border-crossing that the Twitter platform facilitates: socio-economic, national, and linguistic. Because it is freely available and requires a minimal investment of time (especially compared to the process of publishing with a professional publishing house),6 Twitter opens itself up to a more diverse socio-economic group. This diversity applies both to those who write and who read Twitter literature. Many professional writers have indicated that they use Twitter precisely because this platform caters to a diverse audience — often of lower average socio-economic standing than readers of The New Yorker or The New York Times.7 Yet this is only partially true. Twitter's audience was, in fact, initially limited by the high costs of physical devices needed to run it. Indeed, as Aarthi Vadde has shown through her analysis of a different online writing platform, Wattpad, the high prices of physical devices (including smart phones and tablets) serve as an obstacle for lower socio-economic groups in the developing world to participate in these online writing communities.8 But this is becoming less of an obstacle for Twitter users. While Twitter is often used on smart phones and tablets, it is also accessible on computers, which more people have access to through public libraries and initiatives like One Laptop Per Child. Statista reported that as of January 2019, the ten countries with the largest number of active Twitter users are the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Brazil, India, Mexico, Indonesia, and Spain, and at least 20% of Twitter users do not use mobile devices when they tweet.9 The Twitter platform itself is thus increasingly available across socio-economic groups and global economic lines of development.

The international circulation of Twitter intersects with the platform's efforts to break through linguistic barriers. In October 2017, Twitter partnered with Microsoft Bing's Translator Services, which provides automated translations for over 60 languages. Tweets not in the user's chosen language are accompanied with a global icon. When a user clicks on this icon, a translation of the text will appear below the Tweet (see Image 4). Of course, the overlap between languages supported by Twitter and those supported by Bing Translator is more limited than is represented on the Bing Translator site. Among the nearly fifty language preferences officially supported by Twitter, there are several (including Marathi and Gujarati) that are not listed as languages operative for Bing Translator. Alternatively, Bing Translator lists a few languages that are not currently supported by Twitter (including Klingon and Klingon pIqaD). In total, the Bing Translator works for 34 of the languages that are officially supported by Twitter.10 The poor quality of the translations provided by Bing Translator have limited the usefulness of this tool. In response to widespread criticism of Bing, Twitter announced in March 2019 that the Twitter Progressive Web Application (PWA), also known as "Twitter Lite," which allows the user to download Twitter as an app rather than running it through a web browser, would switch to Google translator in an effort to improve services.11 While Google Translate has its own translation issues, Twitter's efforts to improve its translation services are nonetheless colliding with the efforts I examined earlier by the amateur writing community on Twitter to reach greater transnational and multilingual audiences.

The conditions that allow for the creation and global circulation of Twitter literature also undermine its longevity and preservation, making its study difficult. For instance, the average "half-life" of a given tweet is only 24 minutes,12 and it is becoming increasingly easy for Twitter users to delete their past tweets by using programs such as TweetDelete or Tweet Deleter. In order to "document the emergence of online social media for future generations," the Library of Congress announced in 2010 that it would begin collecting and archiving tweets from Twitter's inception in 2006.13 But given Twitter's increasing popularity (both domestically and globally), the Library of Congress discontinued this effort in 2017, and tweets produced after December 31, 2017 are only collected "on a very selective basis" according to "thematic and event-based" issues such as "elections or themes of ongoing national interest, e.g., public policy."14 There are no other ongoing governmental efforts to document and preserve this digital material, which threatens to leave a gap in the literary historical record.

Efforts to preserve and study tweets are further undermined by legal restrictions governing the use of Twitter data. While anyone may theoretically collect Twitter data, Twitter's Developer Agreement and Policy outlines strict limitations about how this data may be shared and stored.15 There are approximately 85 metadata fields ("tweet objects") associated with each tweet (these include the text of the tweet, the username of the individual tweeting, and the time and date the tweet was created). Twitter allows 50,000 tweet objects to be shared per person per day.16 This roughly translates to 625 tweets with full metadata descriptions, which is about 13 percent of the number of tweets related to the anglophone writing community being produced every day.17 One potential way of circumventing this limitation is to simply share the Tweet IDs, up to 1,500,000 of which may be shared per user per month.18 Tweet IDs are unique identifying numbers associated with each tweet that encodes the tweet's metadata. The metadata can then be obtained by running the Tweet IDs through a program or script such as the tweet "hydrator" tool developed by Documenting the Now.19 But there are two problems here: deleted tweets and storage restrictions. The Tweet IDs from deleted tweets are unable to be hydrated, so unless someone else has captured and stored the data from those accounts, the deleted data is gone.20 Additionally, Twitter specifies that no entity may store and analyze Tweets "for a period exceeding 30 days."21 The only exceptions to this rule are members of the academic community.22 Unless, then, the person or entity collecting tweets is associated with an academic institution, that person or entity will be unable to store or share tweets beyond those collected the previous month. Given these limitations, the best way of ensuring the preservation of tweets is for academic researchers to collect and archive tweets and the metadata associated with them.

In their announcement that they would no longer support a comprehensive Twitter archive, the Library of Congress wrote:

Throughout its history, the Library has seized opportunities to collect snapshots of unique moments in human history and preserve them for future generations. These snapshots of particular moments in history often give voice to history's silent masses: ordinary people. ...The Twitter Archive may prove to be one of this generation's most significant legacies to future generations. Future generations will learn much about this rich period in our history, the information flows, and social and political forces that help define the current generation.23

Literary works produced by the amateur writing community on Twitter will be lost if scholars of contemporary literary culture don't value them. And as scholars working with electronic literature and digital humanities issues more broadly have long pointed out, ignoring this literature is a dereliction of duty.24 We must adapt our focus and methods of textual preservation to include the literary works being produced on social media platforms such as Twitter. There is a growing confluence between contemporary literary studies and digital humanities methods, and as academics, we need to be proactive in using digital tools to preserve and analyze the emerging forms of writing within the digital literary sphere.

Christian Howard is the Digital Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at Bucknell University. Her work is located at the intersection of contemporary world literature and the digital humanities, and her ongoing book project examines the ethics of translating multimodal narratives across cultural, political, and linguistic borders.

Keywords: social media, publishing, translation, circulation, network

References

- Simone Murray, "Charting the Digital Literary Sphere," Contemporary Literature 56.2 (2015), 313.[⤒]

- See, for instance, N. Katherine Hayles, Writing Machines (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002); Espen J. Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997); and Marie-Laure Ryan, Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).[⤒]

- For instance, see Ruth E. Page, Stories and Social Media: Identities and Interaction (New York: Routledge, 2012) and Thomas Bronwen "140 Characters in Search of a Story: Twitter Fiction as an Emerging Narrative Form," in Analyzing Digital Fiction, Ed. Alice Bell, Astrid Ensslin, and Hans Rustad (New York: Routledge, 2013. 94-108).[⤒]

- Murray, "Charting the Digital Literary Sphere," 313.[⤒]

- Of course, not all of the tweets tagged by literary hashtags are necessarily works of literature. Some of these tweets promote literary competitions or publication opportunities, and some even serve as writing prompts. So while Twitter literature by the amateur writing community may still be developing as a form, we can nonetheless understand that these works must have the clear rhetorical intent of being literary.[⤒]

- In this way, Twitter literature follows a similar publication model as that promoted by Amazon Kindle. Amazon Kindle's Direct Publishing website boasts: "Self-publish eBooks and paperbacks for free with Kindle Direct Publishing, and reach millions of readers on Amazon." Kindle Direct Publishing likewise allows its writers to publish immediately and promises that Amazon will market the book to its "customers in the US, Canada, UK, Germany, India, France, Italy, Spain, Japan, Brazil, Mexico, Australia and more." Such statements reflect both the freedom from the restrictions mandated by publishing houses (editorial, temporal, and monetary) and the global reach that distinguishes literary works that are published using these online digital spaces. For more information on this topic, see Matt Eatough's discussion of online distribution as a way of circulating African science fiction periodicals more widely and cheaply.[⤒]

- Teju Cole, for instance, has explained that he specifically used Twitter as a publication venue in order to reach "more and more people." Referencing his choice of Twitter for publication platform for "Seven Short Stories about Drones," Cole stated: "[T]he point of writing about these things, and hoping they reach a big audience, has nothing to do with 'innovation' or with 'writing.' It's about the hope that more and more people will have their conscience moved about the plight of other human beings." See Aaron Calvin and Teju Cole, "Author Teju Cole Talks about His New Essay on Immigration, Twitter, and Censorship," on BuzzFeed (March 14, 2014).[⤒]

- Aarthi Vadde, "Amateur Creativity: Contemporary Literature and the Digital Publishing Scene," New Literary History 48, no. 1 (2017): 36-37.[⤒]

- See Statista's "Countries with Most Twitter Users (2019)" and Salman Aslam's "Twitter by the Numbers (2019): Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts" in Omnicore (January 4, 2019).[⤒]

- See language list on "Microsoft Translator: Languages."[⤒]

- Raka, "Twitter PWA Ditches Bing Translator in Favor of Google Translator," MSPowerUser (March 22, 2019).[⤒]

- See Benjamin Rey, "Your Tweet Half-Life is 1 Billion Times Shorter than Carbon-14's," Wiselytics (March 5, 2014).[⤒]

- Library of Congress, "Twitter Donates Entire Tweet Archive to Library of Congress" (April 15, 2010).[⤒]

- Library of Congress, "Update on the Twitter Archive at the Library of Congress" (December 2017).[⤒]

- See Twitter's "Developer Agreement and Policy," Twitter Developer.[⤒]

- Ibid., Section I.F.2.a.[⤒]

- In 2017, there were 1,741,153 tweets related to the Anglophone writing community. This breaks down to an average of 4,770 tweets per day. Hashtag terms used to determine this number include #twitterfiction, #writerslife, and #haiku. For more information about the Twitter-scraping process, see Christian Howard, "Twitterature: Mining Twitter Data," Scholars' Lab Blog (October 1, 2018).[⤒]

- Twitter, "Developer Agreement and Policy," Section I.F.2.b.i.[⤒]

- See DocNow, "Hydrator Tool," on GitHub [⤒]

- For instance, Ed Summers, who has been working with the "Unite the Right" tweets that followed from the August 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, found that over 51% of these tweets had been deleted as of March 2019.[⤒]

- Twitter, "Developer Agreement and Policy," Section I.F.2.b.i.[⤒]

- When these policies were announced, the academic research community vocalized its objections to the distribution and storage limits of Twitter data. To their credit, Twitter accordingly made exceptions for Tweet distribution and storage limits specifically for academic researchers. Academic researchers working with Twitter data may both collect more than 1,500,000 Tweets within a given 30-day period and store those Tweets for more than 30 days "on behalf of an academic institution and for the sole purpose of non-commercial research" (Twitter's "Developer Agreement and Policy," Section I.F.2.b.ii). There are no time limits for how long academic researchers may store Twitter data, but Twitter does clarify that to be considered an "academic researcher," an individual must be officially associated with a given academic institution.[⤒]

- Library of Congress, "Update on the Twitter Archive at the Library of Congress."[⤒]

- See, for instance, "Preserving Digital Information: Report of the Task Force on Archiving of Digital Information" (1996); Terry Kuny's "A Digital Dark Ages? Challenges in the Preservation of Electronic Information" in UDT Core Program (Aug. 27, 1997); Sabine Schrimpf's "Long-term Preservation of Electronic Literature" in iPRES (2008); Marc Bragdon, Alan Burk, Lisa Charlong, and Jason Nugent's "Practice and Preservation: Format Issues" in A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, ed. Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016: 547-563); and The Endings Project at the University of Victoria.[⤒]