The Midwinter Constellation

"I know our / dates did not align, my / day your night, a slight / thing, I tell / myself," I wrote at the end of December 23, 2018 in Beijing. Following Midwinter Day's structure, our group was adding to a shared document using divisions of the day. I was writing half a day off most of the others, and I felt like I was sliding into some dark ravine. I thought about my insertions into the Google Doc: if I wrote late I might always be at the end of the section, which seemed hubristic — but so did writing early, at the beginning of each section. What is simultaneity across time zones, across a day serially segmented like so many split worms?

I decided to write late. Others also added text belatedly; seeing their cursors in the middle of their nights, lingering or leaving the page open — this somewhat broke down the time difference and the day's segmented structure. You might say that I fretted about the date and then I didn't. Or perhaps I still did, "tell[ing] myself." I discover, writing now, that this narrative about plan and process can unfurl in slightly different directions and they all seem true. The forgetting facilitates a story about process, but the story was really just a day, a day when I wrote some lines with others, a day I only really remember now through those lines.

This experience echoes Mayer's processual grapplings on a much smaller scale, a tinny trill after her extended cadenzas. Plan, adjust; plan, adjust — writing across a sin wave. Mayer's archive contains a clipping for a star "Gazer's Guide" and notes about the solstice: the date, the plan, carefully chosen.

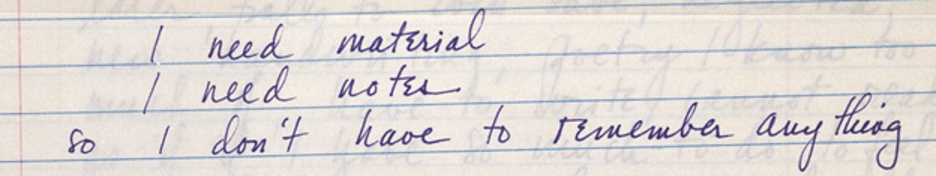

Or is it? There are also notes outlining other possible plans: writing a day prior, or writing from 6-7:30 for a month.1 Mayer says, "I had the idea [for the text] forever, and I couldn't figure out how I would ever do it . . . I figured out I could probably do it [in Lenox, MA] because I was more settled down in one place . . . I could plan everything ahead of time."2 Planning, as so many of us know, involves the making of many lists.

In addition to list-making, Mayer rehearses her dreams. She says, "Nobody ever believes me when I tell them that it was written in one day, but it almost was. I did rehearsals for the first section, which is dreams. I practiced for about two weeks before the December 22 date and tried to sort of fine-tune my dreaming so that when I had dreams on the 22nd I would be good at remembering them and that they would be vivid and worth recording . . . So that was an extension of that day."3 She practices dreaming for the writing, and then the writing itself becomes a performance, while remaining a practice. I like thinking about it as a dress rehearsal. The date suggests an oscillation between a performative present — the "quick" and fleeting current moment — and a "made up" future perfect. Dress rehearsals are potential repetitions that anticipate and envision a future performance, a performance that will have been.

I've been rehearsing a story about process that may or may not match any of our experiences of it, that already anticipates another version of itself. Midwinter Day resists stodgy senses of mastery but is confident in its practice. What wonder, to have these rehearsals, such extensions of each other's days, across plans and forgetting.

Stephanie Anderson is the author of three books of poems, most recently If You Love Error So Love Zero (Trembling Pillow Press). Her essays and poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in La Vague, Momentous Inconclusions: The Life and Work of Larry Eigner, LIT: Literature Interpretation Theory, Rain Taxi, The Sink Review, and elsewhere. She is assistant professor at Duke Kunshan University, and she co-edits the micropress Projective Industries and currently lives in Suzhou, China.

References

- Bernadette Mayer Papers, Box 23 Folder 1, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. Used with permission.[⤒]

- "An Interview with Bernadette Mayer by Stephanie Anderson (Part 3)," Coldfront (blog).[⤒]

- Bernadette Mayer, Bernadette Mayer Lecture (Naropa, 1989).[⤒]