Dark Academia

The Secret History — Donna Tartt's 1992 novel and dark academia's Bible — begins and ends with scholarships. Its narrator, Richard Papen, describes how a scholarship allowed him to attend Hampden College by supplementing an insufficient financial aid offer. As a narrative device, Richard's scholarship sets the novel's plot in motion and lends The Secret History an outsider's perspective on the idiosyncratic college, including the elite clique of Classics students and the mysterious professor at its intellectual center. At the novel's end, we learn that despite experiencing dark academia's depths — murder, addiction, pedagogical manipulation, classism — Richard will continue in the profession by studying Restoration literature in graduate school, thanks to a fellowship. A fish out of water, Richard is the prototype of the interloper-narrator who exposes the corruption and violence that make academia "dark." As with ivied walls and gothic turrets, someone has to pay for scholarships. While we never learn whose largesse makes Richard's education possible, it's easy to imagine his Hampden scholarship and graduate school fellowship deriving from the wealth of donors whose names grace library entryways and endowed chairs.

Private philanthropy is embedded in the structure of contemporary higher education. It's the reason we are constantly solicited for donations from our alma maters and, incredibly, our employers. It's the reason the football coach gets paid millions of dollars, while many campus workers struggle to make ends meet. Like its imagined function in the larger U.S. economy, philanthropy is framed as a win-win solution to higher education's permanent funding crisis, since it does not involve additional tax revenue or tuition increases. While private voluntary funding does in many cases support students and necessary operating expenses, we know that the promise of philanthropy saving the day is a fantasy, one of what Hannah Alpert-Abrams and Saronik Bosu refer to as dark academia's magic tricks.1 In reality, budgets are "balanced" by offloading costs onto students through immiserating debt and by suppressing campus workers' wages. Despite its failure to deliver, the potential of philanthropy animates all manner of university operations: never-ceasing construction funded by capital and endowment campaigns, large fundraising offices, the powerful role played by donor attachments in the persistence of racist statues and songs.

While philanthropy is a fact of academic life, it is also a site of contest. 2021 alone saw several high-profile university scandals directly related to philanthropy: a professor resigned from Yale's Grand Strategy Program citing donor-influence over curricula; an architect working on a UCSB dorm project resigned because of its dystopian design requirements dictated by billionaire philanthropist Charlie Munger; donor-meddling caused UNC to deny Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure. Relatedly, increasing activism around university endowments have called into question why donors who populate Boards of Trustees enforce austerity while endowments see record returns. The Koch brothers' use of university philanthropy to propagate free-market ideology has become so infamous that an entire organization, UnKoch My Campus, was founded to stop it.

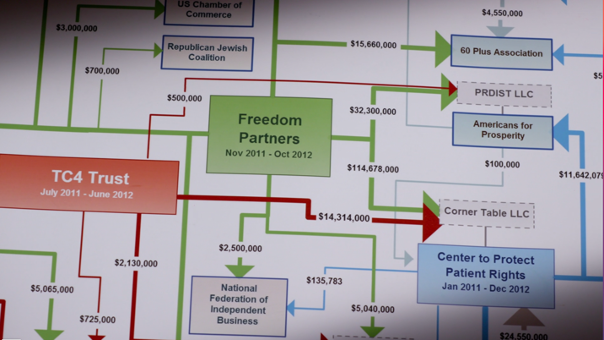

"Dark money" has become a capacious cultural-economic category for describing clandestine transactions of wealth and influence. Investigative journalist Bill Allison coined the term in a 2010 online newsletter, only a few years before dark academia emerged on social media platforms.2 As their common adjective suggests, both categories take semiotic cues from the gothic and its associations with excess, untimeliness, and mystery. They're united by shared commitments to exposing through detective work the rotten undercurrents of institutions supposedly premised on enlightenment. The contemporaneous emergence of — and aesthetic kinship between — dark academia and dark money as descriptors is more than coincidence. Like dark academia, dark money has generated a set of representational tropes that comprise "an aesthetic." The premise of money being "dark" relies on the presumption that flows of capital are typically transparent, accounted for, and knowable by citizens. Dark money is shadowy, unknowable, and malevolent; understanding it requires mediation through investigative journalism. Like the archetypical dark academia protagonist, the journalist becomes a detective who exposes the seedy underbelly of philanthropy. But unlike dark academia, which has found its de facto home on Tumblr and TikTok, representations of dark money are largely the province of an ever-expanding genre of explainer documentaries that "follow the money."3 The central aesthetic figure in these documentaries is less the moodboard than the web of influence visualization (Figure 1), or else the talking-head interview. Infographics and accounts by whistleblowers signal an aesthetic of transparency that promises to demystify philanthropy and its effects. Dark money's cultural artifacts can be categorized as part of a larger genre of financial intrigue that marvels at wealth and aestheticizes it through "complexity" while simultaneously proffering vague demands of accountability.4 Intrinsic to both dark academia and dark money is a simultaneous fascination with and repulsion from wealth. If dark academia is in part a fantasy of an educational experience uncorrupted by profit, then we might say that the idea of dark money as a phenomenon to be named and traced signals a yearning for a version of philanthropy — that is, voluntary redistributions of accumulated wealth — nominally uncorrupted by power.5

***

Dark academia's interloper-narrator trope speaks to a perennial concern: despite liberal-democratic promises of equal opportunity, who really has access to higher education? In the United States, race and racism are central to this question. Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man takes up the racialized logics of exclusion and exclusion-through-inclusion that obtain in the American university — and in doing so, it prefigures certain dark academia texts' concerns with how racism shapes experiences of education, as well the genre's interloper-narrator trope. Ellison's novel is also a site where dark academia and dark money converge, as education, philanthropy, and disturbing entanglements of the two spur the narrator's development, or lack thereof. Suffused with gothic elements, Invisible Man begins with the narrator fighting in a brutal, racist spectacle for a scholarship funded by white boosters, before losing his place at a Tuskegee-like institution because of his role in a wealthy benefactor's visit gone awry. His post-college travails are activated by philanthropic connections, one of which leads to his employment at the paint factory where he's nearly killed. In Invisible Man, a system of private funding and "benevolence" by which white industrialist-donors purport to offer Black Americans access to education and social mobility is in fact premised on extreme violence and exploitation and continually thwarts, rather than improves, the narrator's position.

In this way, Invisible Man is a literary figuration of W.E.B. Du Bois's warning that "education is not and should not be a private philanthropy: it is a public service and whenever it becomes a gift of the rich it is in danger."6 In White Money/Black Power, Noliwe Rooks recounts how Du Bois grappled with the problems of philanthropy throughout his career, a conflict that the novel fictionalizes through the college's Founder, who resembles Booker T. Washington and the favor that his educational philosophies found in white philanthropy. For Du Bois, white education funders' insistence on supporting vocational training over a liberal arts education was their means of developing a low-wage industrial labor force at the expense of Black Americans in the South. Today, we might describe this philanthropic imposition on curricula to exploitative ends as an example of dark money.7 Similarly, as Rooks argues, in the twentieth century the "thicket" of white institutional philanthropy worked behind the scenes of higher education to attempt to influence the development of Black Studies towards reform and integration, rather than radicalization.8

Bruce Robbins has argued that the donor/patron figure of nineteenth-century novels and late twentieth-century cultural artifacts alike acts as a mentor who enables a character's upward mobility, becoming a stand-in for the burgeoning welfare state.9 In dark academia, however, the appearance of a donor indexes Du Bois's warning of a privatized university — where education, which should be a public good, is made available only through dark money's corrupt, often violent mechanisms of individual responsibility and patronage. Here, the private benefactor is not an avatar of the welfare state, but instead an antagonist to it. Historically, state disinvestment in higher education corresponded with racial integration. Accordingly, a rich archive of scholarship on race and higher education has demonstrated that, as labor markets increasingly demand college degrees, and tuition costs are offloaded onto students, Black students' access to higher education has been marked by "predatory inclusion" through exploitative student lending practices that compound existing racial wealth inequality.10 As Mel Monier points out, Black women have the highest amounts of student debt.11

Brandon Taylor's 2020 novel Real Life updates Ellison's portrayal of race and philanthropy with these twenty-first-century questions in mind. The novel's graduate student protagonist Wallace, who is gay, Black, and far from his Alabama home at a midwestern university biology program, attends a fundraising event "at which wealthy white people fling bits of bread at koi and talk in hushed, slurred voices about the changing demographics of the university."12 In a moment that recalls Invisible Man's "battle royal" scene, albeit in a much milder, humorous register, the donors toss crumbs to koi like the funding they bestow on graduate students, as they trade racist dog whistles. Wallace describes meeting the person who funded his fellowship, with the realization that the purpose of the event is donor "worship." In this case, philanthropic funding is associated with thinly veiled racism and an expectation of excessive gratitude towards one's benefactor.

In financial terms, however, for Wallace the fellowship is "generous" and "consistent."13 The novel goes on to trace the interpersonal and financial webs of funding and prestige, following the money that drives competition in his program and a potential trajectory of future upward mobility. While Real Life recognizes that philanthropy offers a financial foothold into academic life, it seems to ask at what cost that inclusion comes. Wallace encounters racism in the form of harassment from his peers and consistent personal and academic denigration from his adviser, what he refers to as "struggling up the channel of other people's cruelty" as he contemplates leaving his program for a "real life" at the novel's end.14 The confluence of dark academia and dark money through the figure of the benefactor in Invisible Man and Real Life points to the fact that inclusion in educational institutions does not necessarily equate with or fulfill promises of social mobility or well-being.

***

While in Invisible Man and Real Life the confluence of dark academia and dark money comes to the fore through a focus on individual characters and their relationships with benefactors, in contemporary television the two modes converge through plot-driving transactions that satirize philanthropy and education. The 2021 Netflix series The Chair is in part about the personal, professional, and institutional compromises that Ji-Yoon Kim, the first woman of color chair of the English department at a small liberal arts college, must make to keep the department afloat amidst declining enrollments. In a compromise that fuels one of the show's central conflicts, Ji-Yoon accedes the choice of the annual Distinguished Speaker to a donor at the insistence of a dean. The meeting's setting — in the donor's well-appointed home — represents an aesthetic confluence between dark money and dark academia through their shared interest in wealth, as well as in the clandestine. The scene is a negotiation, as the donor, a wealthy white woman, uses the private sphere of philanthropy and a meeting in her home to influence the curricula of the college that she is "supporting." Her choice of speaker — David Duchovny — is both ridiculous and a personal, political problem for Ji-Yoon as she must choose him over her colleague and friend, Yaz McKay, who is also the only Black professor in the department. Ultimately, Ji-Yoon ekes out a philanthropic win, by way of another transaction in which she turns Duchovny from aspiring professor to donor through the promise of an honorary doctorate. Once again, philanthropic wheeling and dealing takes place in the donor's home. We might read the domestic setting of these scenes as another manifestation of what Mitch Therieau, drawing on Olivia Stowell, identifies as the sense of an enclosing academic commons (or, perhaps one that was never truly common to begin with).15 The chain of events is played for laughs, but also indicates how dark academia and dark money converge in their understanding of higher education at its worst: as a site of transactions that undermines its supposed meritocracy and appeals to truth.

An episode of the financial soap opera Billions, fittingly titled "Beg, Bribe, Bully," undercuts such appeals to truth through a philanthropy plot staged at a boarding school. While dark academia texts are largely set on college campuses, they are occasionally set in elite private secondary schools, which as their "prep" moniker suggests, prepare students for continued elite education that hinges on wealth's aesthetic and ideological trappings. In the episode, hedge-fund billionaire Bobby Axelrod tries to avert his son's expulsion from school after he takes out the nearby town's power grid while mining cryptocurrency by bribing the headmaster with a donation (Figure 2). In accordance with the show's depiction of institutional corruption, the audience, like Bobby, expects the headmaster to concede. Instead, the headmaster delivers a self-righteous lecture in a tenor that calls to mind a certain genre of high-minded defenses of the liberal arts. Bobby, however, prevails when he threatens to expose how the headmaster has been using refugee students whose scholarships are funded by philanthropy as domestic slave labor. Bobby's win means that his son gets back into school and that he gets to give a speech to students extolling the free-market logic that often underpins the corporatization of education, while the headmaster's grandiose speech appealing to the value of truth becomes a farce.16

This scene, like many in Billions, attempts to appeal to what we might understand as "both sides" of the so-called quality TV audience: viewers who cheer for rich, white male anti-heroes and those who read such shows as a critique thereof. Philanthropy is the arena that allows wealthy donors like Bobby to buy second chances for their children and, perhaps even more damningly, gives institutions cover to exploit their most vulnerable students — and to hide this exploitation behind a screen of "now more than ever" platitudes about the value of the liberal arts.

Here, again, dark money and dark academia's convergence is a joke. But, as the mise en scène suggests, the dark money-dark academia industrial complex is also horrifying. In Billions and The Chair ghastly portraits of donors preside over under-the-table negotiations carried out in smoke-filled rooms — a gothic visual vocabulary that registers the seediness and excess of dark money/dark academia. The dark humor of satire, which Real Life and Invisible Man also offer glimmers of, foregrounds mutual corruption as university administrators willingly concede to and, in fact, court dark money donors.

***

While the knowing wink and nod of satire could be read as a gesture to downplay the problem of university philanthropy, the blunt cynicism of these novels and shows figures higher education's corruption as an open secret. The confluence of dark academia and dark money through representations of benefactors and of philanthropic arrangements indexes both an anxiety that education has become wholly transactional and a creeping suspicion that the terms of this transaction have been broken. In the terms of this transaction, in exchange for paying tuition, students receive the necessary credentials to escape a life of so-called "low-skilled" work. However, stagnating wages, inflation, and insurmountable student debt make these terms untenable and mean that academia, dark or otherwise, is not an escape from precarity.

Despite the promise that the benevolence of private funders can ensure the future of higher education institutions, philanthropy has in many cases exacerbated the sector's funding crises. The rise of restricted donations, for example, means that philanthropic money does not pay for already-existing operating needs, but instead, funds specific, donor-driven initiatives that often create new programs and in turn, additional expenses for which universities foot the bill. In the case of institutionally prioritized capital and endowment campaigns, philanthropic dollars fuel higher education's financialization. The presence of philanthropy haunts the university, acting as a coercive force not subject to accountability by students, faculty, and other campus workers. Universities and their endowments accumulate money, through the twinned forces of philanthropy and financialization. These surpluses never address the precarity that academia's adjunct and debt dependent business models necessitate, and in fact only further entrench it by keeping overheads down to make endowment figures go up. Dylan Davidson points out that Yale's "For Humanity" fundraising campaign sits at the intersection of dark academia and dark money in deploying neo-gothic symbols associated with the donor-ghosts of its past to deflect from what it is today: "a hedge fund with a university stapled to it."17

As Davarian Baldwin recently noted, Yale's campaign title also begs the question: whose humanity is university philanthropy serving, exactly?18 That is, who does the university imagine as benefiting from this fundraising, and, just as crucially, who is excluded, ignored, tokenized, or subsumed under the rubric of closed-door transactions? Dark academia and dark money give aesthetic form to the kinds of exclusions Baldwin identifies, albeit in a way that can't quite disinvest from a retrograde faith in personal transformation and institutional salvation. If only, as dark academia suggests, universities could be rid of precarity, exclusion, predatory inclusion, racism, misogyny, and classism — then we could pursue a life of pleasure. Dark academia, and its promises of a life that is not only aesthetically and intellectually satisfying but also financially secure, may be little more than a marketable fantasy. So, however, is dark money discourse's supposition that financial transparency will automatically bring accountability and justice. Both fantasies are animated by a desire for truth and its power to reform institutions for better. Perhaps, though, the bleak moral calculus that saturates representations of higher education suggests, finally, that we are long past the point of reform.

Annie Bares (@abares981) is a PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. Her dissertation studies the relationship between the political economy of philanthropy and contemporary literature. Her writing has appeared in MELUS, the E3W Review of Books, The Nation, and elsewhere.

References

- Hannah Alpert-Abrams and Saronik Bosu, "What's Hope Got to Do with it?" Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022.[⤒]

- See Michael E. Hartmann, "The Etymology of 'Dark Money,'" Philanthropy Daily, July 23, 2019. [⤒]

- #Darkmoney has only garnered 2.6M views on Tiktok, compared to the 1.6B of #darkacademia. A particularly funny #darkmoney TikTok speculates about fictional characters who would have "contributed 'dark money' to the [January 6 U.S. Capitol] insurrection;" Mr. Big, George and Lucille Bluth, Sarah Michelle Geller in Cruel Intentions are featured among others, to the tune of Lady Gaga and Beyoncé's "Telephone." Ali Golub (@alibrooke4ever.org), "This feels both too highbrow and too silly for TikTok," TikTok, January 14, 2021.[⤒]

- The cephalopod-as-symbol bridges dark money and financial intrigue. Matt Taibbi famously used a great vampire squid to metaphorize Goldman Sachs's operations. See Matt Taibbi, "The Great American Bubble Machine," Rolling Stone, April 5, 2010. Several different versions of the "Kochtopus" have surfaced to make visible the Koch Brothers' dark money influence web. See Greenpeace, "The Kochtopus Media Network," last updated December 18, 2018. [⤒]

- Figure 1: Dark Money: The Influence of Corporate Money in our Elections, directed by Kimberly Reed (Boston: PBS Distribution, 2018).[⤒]

- W.E.B. Du Bois, "The Future and Function of the Private Negro College,"in The Education of Black People, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001), 142.[⤒]

- Noliwe Rooks, While Money/Black Power: The Surprising History of African American Studies and the Crisis of Race in Higher Education (New York: Beacon Press, 2006), 103.[⤒]

- Rooks, White Money/Black Power, 29.[⤒]

- Bruce Robbins, Upward Mobility and the Common Good: Toward a Literary History of the Welfare State (Princeton University Press, 2007).[⤒]

- See Louise Seamster and Raphaël Charron-Chénier, "Predatory Inclusion and Education Debt: Rethinking the Racial Wealth Gap," Social Currents 4, no. 3 (2017): 199-207. See also Tressie McMillan Cottom, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy (New York: New Press, 2017).[⤒]

- Mel Monier, "Too Dark for Dark Academia?" Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022.[⤒]

- Brandon Taylor, Real Life (New York: Riverhead Books, 2020), 80.[⤒]

- Taylor, Real, 81.[⤒]

- Taylor, Real, 310.[⤒]

- Mitch Therieau, "The Novel of Vibes," Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022.[⤒]

- Figure 2: Billions, season 5, episode 3, "Beg, Bribe, Bully," directed by John Dahl, aired May 17, 2020.[⤒]

- Dylan Davidson, "To Be Transformed," Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022.[⤒]

- Davarian Baldwin, "For Whose Humanity?" Yale Daily News, October 11, 2021. [⤒]