Dark Academia

A joke has been going around. Maybe you've heard it, or a version of it: "_____ isn't a university. It's a hedge fund with a university stapled to it." I think I first heard the joke when I played a small part in organizing for funding extensions at the very beginning of the pandemic, back when we were all figuring out how to use Zoom. Yale's administration, anticipating stock market contractions, had drawn a bright line around the endowment. It is not a rainy day fund, they wrote to us in emails and press releases. It could not be "spent" to alleviate the effects of the pandemic. On the contrary, doing anything to harm the endowment would create an unequal learning environment for future generations of Yale students and instructors — this was a parity issue, and we graduate students who'd had the good fortune to begin our studies before the impending economic downturn were the lucky ones.

Between seminars we had scrambled to move online, graduate students held impromptu town halls and organizing meetings to discuss our needs and fears. We signed public letters demanding universal extensions for current PhD students and contract renewals for non-ladder faculty, reasoning that a case-by-case approach would result in endless red tape and potentially traumatic litigation over whose experience of the pandemic "counted" as a sufficient disruption to their research. The university came up with a clever workaround: they would defer the question of funding extensions to departments themselves, stipulating that whatever decisions departments made must be budget-neutral. For every six-year extension granted, departments would have to cut one future admissions slot. Department chairs and directors of graduate studies mostly agreed to this deal: across the humanities, cohorts were cut in half or cut in their entirety to accommodate funding extensions. In various meetings, faculty who had weathered the 2008 financial crisis had an agitated look about them — they expected to see the same administrative knives that had cut their budgets and accelerated the pace of adjunctification, with twelve years of sharpening. These were emotional, confrontational meetings: on one side, early-career scholars fearing that the pandemic would deprive them of their already scant chances at finding tenure-track employment at the end of their PhDs; on the other, a worried handful of senior faculty who had observed the erosion of their budgets for decades and feared for the longevity of their departments. Yale's administrators had cannily shifted the terrain of political tension from demands for one-time expenditures to the relationships between students and their advisors. And it worked: whatever it might mean in the short term, the "budget-neutral" solution would at least ease graduate student complaints and keep PhD programs running.

But within a few weeks, it became clear that the stock market (and thus the endowment) was not just holding steady. It was growing at an unprecedented rate. Last October, the university announced that its endowment had grown by 40.2% in the previous fiscal year, bringing its total to over $42.3 billion.1 Predictably, the austerity policies remained in place.

***

As the professors lucky enough to keep their positions in academia through the Great Recession knew, the bureaucratization and profit-maximization of university education is old news — the pandemic just provided me with my first direct experience of it. That experience offered a different sort of education than the one I thought I'd be getting when I came to graduate school. Indeed, the meaning of experience, I want to argue, has been transformed along with the educational institutions designed to curate and cultivate it. Higher education has become a commodity, purchasable at the average price of $30,000 in student loan debt.2 The nature of this commodity is both material and psychic: college students receive marketable professional skills as well as a set of transformative experiences that will accompany them into adulthood as life lessons, good times, broadened intellectual horizons, refined aesthetic sensibilities, and so on. And like any commodity, the internet has allowed us to get hold of pretty good copies for almost nothing.

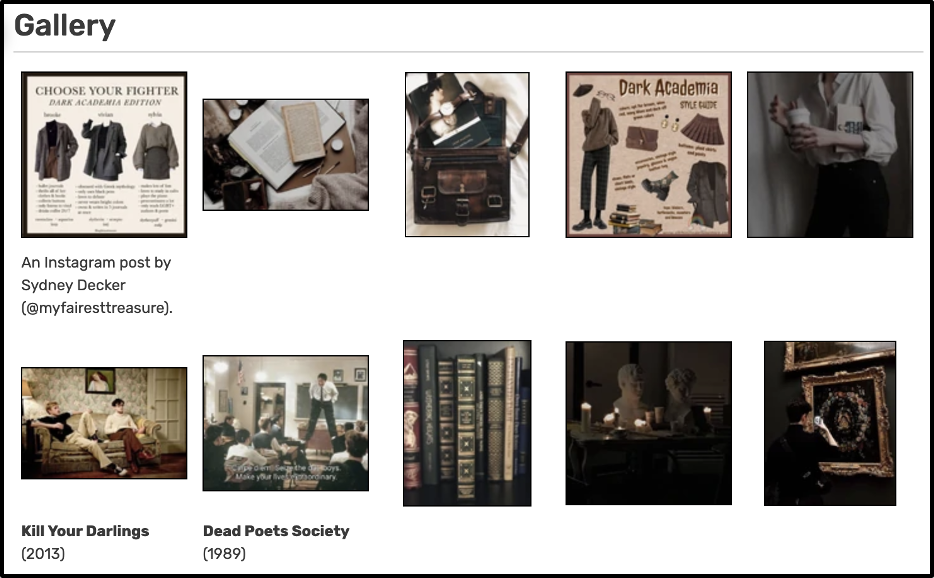

A number of essays in this cluster demonstrate how the literary genre and online aesthetic known as dark academia is bound up in, or at least contemporaneous with, the financialization of higher education — and not just on the part of readers and internet users. Annie Bares links dark academia to dark money, showing how universities themselves deploy the aesthetics of gothic architecture and wood-paneled libraries to disguise their transformation into high-tech financial institutions with obscure and unsavory investment portfolios.3 The promotional video for Yale's 2021 capital campaign (bearing the munificent title "For Humanity" and seeking to increase the endowment's value by an additional $7 billion) features a crepuscular shot of Sterling Memorial Library, the university's faux-gothic centerpiece, which was completed in 1931 and named after a corporate lawyer who represented Standard Oil.4 Incandescent lights glow through the stained glass windows in the library's nave as twilight sinks its facade into blue-tinted shadows. A pair of black iron lamp-posts gleam in the mid-ground. Whether Yale intends it or not, this is dark academia — and dark money — par excellence.

To highlight the aesthetic overlap between dark academia and university marketing materials is to recognize that in both cases we are dealing with simulacra, with a romanticized pastiche or performance of historicity. If dark academia is a practice of collecting and curating signifiers of old-fashioned elite education, what could be more dark academia than a settler-colonial university appropriating gothic motifs from Medieval Europe for a library completed during the Great Depression? In this sense, the making of a university campus into an architectural collage bears a sort of symmetry to the blogger posting dark academia moodboards or the YouTube user setting photos of chandeliers and bookcases to hour-long classical music playlists — with the obvious (and very important) distinction that universities own and control capital while the average moodboard-maker, one assumes, does not. The point is that this romantic fantasy of education is constructed from above and below, simultaneously.

To point out symmetries is not to draw equivalences: as Ana Quiring points out, if dark academia "idealizes narrow and Eurocentric standards of education," it also "democratizes their trappings and texts by making them available as fashion. Though you might not be able to attend private boarding school, you can listen to Chopin, read Waugh, and buy scuffed black brogues from the thrift store."5 In her essay for this cluster, Mel Monier shows how Black women content creators have mobilized and expanded the category of dark academia aesthetics, "reframing their relationship to academic spaces that are often elitist, inaccessible, and hostile to women of color."6 Such processes of democratization play out in the remarkable number of syllabus-like lists in dark academia spaces online. Scrolling through dark academia's "Aesthetics Wiki" entry (whose collective authorship is itself a fascinating act of meta-collage), one finds not only extensive lists of novels, films, anime, and musical artists, but also a section of prominent criticisms of the aesthetic including "Aestheticization of unhealthy behavior" and "Western Eurocentrism."7 Dark academia's facilitation of a kind of canon-formation-from-below, writes Quiring, "shifts, and diminishes, the claim whiteness makes to elite academic spaces."8 Dark academia's leatherbound gloom — the promise of late nights reading the classics by lamplight in cathedral-like libraries — appeals to, and serves, endowment managers and TikTokers alike.

***

Dark academia, as both a marketing strategy and a collective practice of online collage, illustrates how the concepts of "education," "experience," and "aesthetic" are bound up with one another — and how the transforming economic structure of academia has shifted our understanding of each of these concepts. The last of these, "aesthetic," has a particularly wide-ranging variety of uses. Since its neo-gothic facelift in the 1920s and 30s Yale has used architectural aesthetics to present itself to prospective students and donors as an ancient institution of higher learning. An internet user might describe a well-assembled collage as "so aesthetic," denoting a particular attention to the curatorial conventions of online image-making. And dark academia is itself "an aesthetic," a genre of cultural practice characterized by a shared iconography or set of references.

Saturating critical discourse, circulating online, structuring our relationships with the institutions that employ us: what is this elastic concept of aesthetics/the aesthetic/an aesthetic, anyway? While "aesthetics" proper is often restricted to questions of art and artistic merit, the proliferating usages of the term suggest that, following theorists from Walter Benjamin to Susan Buck-Morss, aesthetics in its fullest sense refers to "the sensory experience of perception" — not only a privileged class of special objects or experiences, but the broader category of everything that happens to us.9 Broadly construed, aesthetics is nothing less than the domain of experience itself. To label an object "aesthetic," or to summon the discourse of aesthetics in order to examine it, is to call special attention to its experiencedness, its ability to improve or transform us simply by being seen, touched, felt, or perceived. The cultivation of Experiences That Transform is at the heart of the concepts of the university and the so-called liberal education.

As "an aesthetic," dark academia takes up this idea of education and transforms it into a fantasy of intellectual and aesthetic rapture — a yearning for an experience of art and literature which might shake off our alienation and help us experience things anew in all their immediacy. There may be no better example of this than dark academia's ur-text, The Secret History, in which a cadre of tweed-clad Classics students perform ancient Bacchanalian rituals in search of a more raw and unmediated experience than they can find in the culture of 1980s America.10 We might also recall that the novel's protagonist, Richard Papen, can barely afford to attend the thinly fictionalized version of Bennington College where the book is set — a reminder that dark academia has been, from the start, a fantasy of imaginary access to (cultural) capital. Tartt's novel is about all sorts of attempted transformations: from a lower-middle-class community college dropout into a member of the educated elite; from Reaganite political subjects into ancient Greek cultists.

We might read The Secret History as satirizing its characters' pathological desire for "authentic experience" under late capitalism — especially under the auspices of elite education. The novel's (surviving) characters ultimately end up playing exactly the social roles that their economic positions might have predicted: the rich members of the cohort become disaffected aristocrats, and Richard ends up in a graduate program writing a halfhearted dissertation on Jacobean drama — hardly the raw and rarefied life he envisioned for himself while studying The Classics. University education and its putatively transformative aesthetic cultivation are ultimately a momentary diversion from predictable class trajectories. These experiences precisely do not transform the novel's characters into something other than what they had been when they arrived.

***

In placing The Secret History at the center of an online aesthetic formation, have the dark academicians of Tumblr and Instagram and TikTok misinterpreted its cynicism about the power of reading books in castles to turn us into better and more authentic people? Or have they internalized it, recognizing that anyone with internet access can cultivate their own set of vibes and experiences without taking out tens of thousands of dollars in student loans? I'm inclined to take the latter option, if only because it would demonstrate a weakening, rather than a naive shoring-up, of the experience-commodity offered by the neoliberal university.

The student debt crisis and the adjunctification of the academic workforce are parallel developments which inform but do not completely explain this shifting attitude toward the university and its supposed power to dispense transformative experiences to its tuition-paying students. For all of its democratic and canon-undermining qualities, dark academia also operates a lot like a market category, both in the sense that it is now a legible genre to publishers, and in its relation to other aesthetics including (according to the Aesthetics Wiki) Art Academia, Chaotic Academia, Classic Academia, Fairy Academia, Light Academia, Natural Philosophy, Romantic Academia, Theatre [sic] Academia, and Writer Academia.11 Whatever dark academia's merits may be as a strategy for displacing the university as the privileged site of aesthetic cultivation, its status as an identificatory menu item aligns it firmly with the same regime of consumer choice that holds sway over the neoliberal campus.

This proliferation of online "aesthetics" as identity-commodities is bound up in a deep-rooted ideology of selfhood — one which has co-opted the categorization and commodification of experiences and, in Cressida Heyes' terms, reduces individual autonomy to "an interminable series of self-determining moments."12 In her study of the fraught status of "experience" under contemporary capitalism, Heyes observes that this category occupies a strange discursive position both as something that happens to us and as a commodity we possess and use to define ourselves. As a notable and troublesome example, she turns to Michel Foucault, who in the second and third volumes of his unfinished History of Sexuality examines the sexual and personal habits of ancient Greek and Roman men, which he terms "arts of existence": "those intentional and voluntary actions by which men not only set themselves rules of conduct, but also seek to transform themselves, to change themselves in their singular being, and to make their life into an oeuvre that carries certain aesthetic values and meets certain stylistic criteria."13

Heyes's study of Foucault illustrates how art, ethics, and experience itself are bound up discursively in the idea of "an aesthetic," and how this discursive linkage plays out in an economic system in which the basic unit of self-determination is the individual consumer choice — and in which the traditional chief purveyor of transformative experiences, the university, grows more obviously profit-motivated by the day. As Quiring and the Aesthetics Wiki syllabus-makers show, the university is losing its monopoly on the curation of aesthetic and intellectual experiences for young inquiring minds — and, perhaps more crucially, they show that the crudely economic label "monopoly" is an apt one to begin with. Anyone with a Twitter account can now go back and forth about Hegel with a Yale philosophy professor any time they want. Or, as Amelia Horgan put it for Jacobin, "Dark academia offers a fantasy of the university experience that many students felt they were forced by the pandemic to forego."14 If experience and its cultivation are commodities imputed to transform us into better versions of ourselves, dark academia shows that we don't need to purchase them at the price of admission.

***

I don't want to be transformed by Yale anymore — at least, not in the way it wants me to want. Maybe it's because I'm not having the kinds of experiences I'm supposed to: for three quarters of my time in coursework, "Yale" meant little more to me than the first word in the URL I clicked on to log onto Zoom class from the desk in my childhood bedroom in Texas. More likely, it's because I watched administrators nickel-and-dime department officers, demanding budget-neutral solutions to the pandemic while sitting on tens of billions of dollars in hoarded wealth. Even more likely, it's because I've watched the university insist on its generosity to the city of New Haven while enjoying a property tax break to the tune of nearly $150 million,15 all while the city's Black and brown residents get sick and die of COVID-19 in disproportionate numbers.16 When you climb the steps (or, more likely, take the elevator) to the upper floors of Sterling Memorial Library, you can see past the point where the gothic architecture stops — beyond the corniced fantasy of personal transformation that comes from reading Cymbeline or Songs of Innocence and of Experience in a wood-paneled library.

In an account of her experiences in the 2016 campaign to unionize Yale's graduate workers — a particularly intense episode in a labor struggle which has lasted for over thirty years — Alyssa Battistoni poignantly describes the psychosocial demands that organizing placed on her: "I struggled to be different: the version of myself I wanted to be, someone who could move people and bend at least some tiny corner of the universe."17 After spending the better part of a year and a half organizing to win a union for graduate workers at Yale, I'm struck by the simplicity and difficulty of that "struggle to be different." Since childhood, I've invested my self-worth in my ability to think and articulate, to produce literary insights from the cauldron of my subjective observations. I am not saying that I've succeeded at this — just that it's the only way I have understood myself for the first twenty-six years of my life.

Now I want to be someone else: someone whose sense of self-worth derives not from individual accomplishments but from shared purpose. Someone who is able to talk to my peers and build trust and persuade them to join in collective imagination and collective action. I want to be transformed into a version of myself — or not myself — with the stamina and courage required to get up day after day and ask people I've never met before if they want to talk about their lives, and the ability to understand struggles other than my own. Or better yet: I want to stop being so concerned with the kind of person I'm becoming and disappear into the work of improving our working conditions. "Organizing," Battistoni writes, "burrows into the pores of your practical consciousness and asks you to choose the part of yourself that wants something other than common sense."18 It asks you to think of yourself as something other and more than the core of private self-reflection that you meet, alone, at the very end of each day — and it asks you to see yourself instead as fundamentally connected to and responsible for others.

This is the way I want to be transformed. For better or worse, it came at the expense of the fantasy of transformation that the university offered me when I arrived. But there is a reassuring difference between these two visions of what my time in academia will be like: in the dark academia fantasy, those oh-so-special experiences were things that were supposed to happen to me. I kept waiting for the right mentor to take an interest in shaping and developing me, for the perfect passage of theory to strike me like lightning in the vaulted seminar room. I wanted someone or something else, bigger and older and wiser and smarter than myself, to transform me. Not anymore: for all of its difficulties, for all the coming struggles and setbacks and — eventually — celebrations, the academic labor movement offers another possibility entirely. It offers us a transformation that we must make for ourselves. As long as it takes.

Dylan Davidson (@davidson_dylan) is a PhD student at Yale University, where he is beginning a dissertation on memoir, phenomenology, and neurodivergence. His research examines the relationship between the brain as a scientific explanatory object and the lived experience of mental illness and other forms of neurodiversity.

References

- "Yale endowment earns 40.2% investment return in fiscal 2021," YaleNews, October 14, 2021.[⤒]

- "Student Loan Debt Statistics," Education Data Initiative, last modified November 17, 2021.[⤒]

- Annie Bares, "Dark Academia, Dark Money," Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022.[⤒]

- "About the Campaign." For Humanity: The Yale Campaign, accessed December 29, 2021; For Humanity: The Yale Campaign, accessed February 6, 2022.[⤒]

- Ana Quiring, "What's Dark about Dark Academia?" Avidly, March 3, 2021.[⤒]

- Mel Monier, "Too Dark for Dark Academia?," Post45: Contemporaries, March 15, 2022.[⤒]

- "Dark Academia," Aesthetics Wiki, accessed December 29, 2021.[⤒]

- Quiring, "What's Dark"[⤒]

- Susan Buck-Morss, "Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin's Artwork Essay Reconsidered," October 62 (Autumn 1992), 6.[⤒]

- Donna Tartt, The Secret History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992).[⤒]

- Amy Gentry, "Dark Academia: Your Guide to the New Wave of Post-Secret History Campus Thrillers," CrimeReads, February 18, 2021; "Dark Academia," The Aesthetics Wiki.[⤒]

- Cressida Heyes, Anaesthetics of Existence: Essays on Experience at the Edge (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 7.[⤒]

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume II: The Use of Pleasure (New York: Vintage, 1990), 10-11. Emphasis mine.[⤒]

- Amelia Horgan, "The 'Dark Academia' Subculture Offers a Fantasy Alternative to the Neoliberal University," Jacobin, December 19, 2021.[⤒]

- Allan Appel, "They've Got Yale's Number," New Haven Independent, November 14, 2019. Yale's meager contributions to the city, contrasted with the almost incomprehensible scale of the University's endowment wealth, has fuelled the city-wide Yale: Respect New Haven movement, which has mobilized a coalition of grassroots advocacy groups and union locals to demand that the university "pay its fair share" to New Haven.[⤒]

- Mackenzie Hawkins, "Early data reveals COVID-19 disproportionately impacts people of color in New Haven," The Yale Daily News, April 9, 2020.[⤒]

- Alyssa Battistoni, "Spadework: On political organizing," n+1, Spring 2019.[⤒]

- Battistoni, "Spadework."[⤒]