Feel Your Fantasy: The Drag Race Cluster

Before I watched any Drag Race, a first date showed me a clip of Season 9's finale. Shea Couleé and Sasha Velour are about to engage in a semi-final lipsync battle that will lead up to the Lipsync for the Crown. In a performance of Whitney Houston's "So Emotional," here, and everywhere, feeling and reading entwine. You probably already know how it went: Shea is dripping in patent leather, and as the song starts, her movements are sharp and emphasize popped and curved shoulders, elbows, and knees. Sasha Velour rips rose petals from their stem, drawing eyes to her golden sleeve-length gloves, knotted at the ends on both forearms with ribbons (establishing both a motif and a vessel for its reemergence later in the performance). Shea's outfit recalls Whitney Houston in the song's music video, and with every turn the light slides unevenly across the surface of Shea's outfit, creating new contours, highlighting new peaks and slopes, micro-movements of stage-lighting across leather animated by sharp, pointed choreography. The Ru-les of the reveal have established expectations: a queen may take something off to reveal more of an outfit underneath, or an entirely new look, or even skin — all this skin, honey — and the narrative of the performance is thus refashioned.

With the chorus — I get so emotional! — Sasha pulls her glove off, tossing rose petals into the air. Another golden glove, more rose petals. Sasha lifts her wig slowly, and even more petals pour out, flowing red falling into pools at their feet. Sasha used the generic expectation of the reveal (of layers underneath layers, of something hidden and hiding) to surprise the audience and judges with something unexpected (rose petals), and ultimately snatch the crown. Shea and Sasha may wear different materials, but their looks are both fabrications of interpretation. The interpretation of a theme, or "category," is the queen's performance, narrated through the play of ornaments and clothing; through the embodied movements and mannerisms and character lived in the performance; through attitude, and even allusion and citation, as John Lurz argues in his contribution to this cluster. Lurz describes the repetition of Ru's call for an amen is "as much about the injunction to love ourselves as [it is] about the call for verbal affirmation that accentuates and actualizes it."

In Drag Race as elsewhere, queer cannot "mean" everything, cannot contain everything that it gestures towards, though it can hold space for negativity and absence as a disruptor, or additive presence as identity. It can disorient the subject, as many of the essays in this cluster explore. Queerness can also congeal into a genre — of experience, of style, of form, or content. Mel Y. Chen argues in Animacies that the "bleeding" of "queer into diffuse parts of speech" reveals the term "queer" itself to be indeterminate.1 Defining it, or settling on supposedly "authentic" examples is difficult, perhaps impossible. Chen cites the linguist Arnold Zwicky to determine the limits and possibility of reclaiming words: "the many, often contested senses of a word" are what through lexicographic methodologies "must be documented" to determine how and if a word has been reclaimed. Queer, as a sign — and depending on the positionality and context of the speaker and interpreter(s) — is capacious; who is to say who has successfully reclaimed it? As a noun, it may indicate a non-heterosexual person or a slur. As a verb, it can signal transgressive behavior, a disturbance in the order of things. As an adjective, it can be used with a positive or negative valence to indicate something incorrectly out of place. Chen effectively contraposes this seemingly alternative origin point for queerness against the "invisible operations of whiteness" at play in the commonsense view that a "turning point in the history of 'queer theory'" and a signal for the "shift from lesbian and gay to queer" is Italian scholar Teresa de Lauretis's discussion of the term in 1990 as editor of a special issue for the journal differences, entitled Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities — which was itself a syntactical theorization of queer's discreteness.2 Talib Jabbar explores the tendency for queerness to, at times, attempt to elide questions of race. In his essay for this cluster, "Drag Queens in Stars and Stripes," Jabbar builds on Jasbir Puar's notion of homonationalism to analyze the nationalistic instantiation of queerness in Drag Race as it recasts racializing logics and imperial militarisms in drag drawing out how, as he puts it, the "prerequisite for RuPaul's form of queerness is nationalism."

Even something typically subsumed under queerness — the idea of "transness," as explored by Aren Z. Aizura in Mobile Subjects — is accompanied by the "assumption that transness is the same for most people."3 E. Patrick Johnson, in "'Quare' studies," writes about the word "queer" and its failure to mean enough, or too much, and especially regarding its failure to address the real, material consequences and concerns of racialization:

Because much of queer theory critically interrogates notions of selfhood, agency, and experience, it is often unable to accommodate the issues faced by gays and lesbians of color who come from 'raced' communities. Gloria Anzaldúa explicitly addresses this limitation when she warns that "queer is used as a false unifying umbrella which all 'queers' of all races, ethnicities and classes are shored under" (250). While acknowledging that "at times we need this umbrella to solidify our ranks against outsiders," Anzaldúa nevertheless urges that "even when we seek shelter under it ['queer'], we must not forget that it homogenizes, erases our differences" (250).4

In her contribution to the cluster, Jewel Pereyra reminds us how queerness can also manifest in Afro-Filipinx intimacies, like those shared between Latrice Royale and Manila Luzon, which can challenge universal or one-dimensional representations of queer relationality. Through this cluster and my studies I am coming to realize that queerness emerges just as much in the where and when — in relation, in specific positions, in embodied and particular perspectives. Queerness's capacity to mean is also its disadvantage: it can become homogenizing. What I find so interesting about RuPaul's Drag Race is how the show and its spin-off material represent particular (yet universalized) forms and figures of queerness that are mediated through layers of footage, editing, production, advertising, and the paratext of digital objects from or about the show, like memes. The show is heavily invested in the mass production of vernacular and figures of queerness, composed through the truths and fictions of the contestants and the contest being rearranged into compelling narrative and characterization — reality television realness.

In short, it produces queerness, a queerness consolidated within the limits, frames, and terms of its show and media universe, but also capable of proliferating across digital spaces, inspiring new ways of reading and encountering the media. In this cluster, Marcos Gonsalez sits with what he calls Crystal Methyd's "quirky" aesthetic, the role of props in ornamenting drag, and the sometimes unsettling ways drag can come to us. Gonsalez writes, "RuPaul's televisual empire holds a firm grip over what kinds of drag art and styles popularly acceptable, praiseworthy, and profitable," and presents Methyd's "piñata drag" as a welcome reprieve from that grip. The show's foregrounded artifice and conceit is that the queerness on your screen is not immediate but mediated through layers of meaning, some sedimented or attenuated, and others rising to the surface. As media, plural of medium, RuPaul's Drag Race communicates the elements of (particular) kinds of queerness which pass through its branded membrane. They become universalizable, abstract, general, like the "coming out" trope — all queers go through this. The show does not seem to think it an impossible task to define what constitutes "queer." If queerness lies as much in relations and acts of interpretation as it does in animating people — trajectories and positions — then queerness, with meanings that always spill over, can only gesture towards a constellation; in Drag Race, it is a montage of citation, self-reflexivity, affiliation, relation, and creation — and even sound, music, and voice, as Gabriel Dharmoo writes in their multimodal cluster essay of curating their transformation into Bijuriya, playing with breath with body with voice with being.

As a reality competition show embedded in the fabric of globalizing capitalism, Drag Race connects its mass production of vernacular and figures of queerness to Paris Is Burning (1991) by situating itself as an inheritor and purveyor of its vocabulary. Paris Is Burning punctuates its footage of montages and monologues with words written in white font against a black background. These words linger momentarily, enough to seem like a vocabulary word on a chalkboard. The audience is receiving an aesthetic education in the form of a grammar lesson. These words are specific to the New York drag ballroom scene — and the people — being documented. The film connects definitions with lived and embodied experience, providing loose and indeterminate interpretations of meanings through linking but not equating many personal stories. These narratives are about racism, displacement, poverty, homelessness, family estrangement, violence, sex work, the fascination and ire of spectators and customers, and fantasies of wealth, power, celebrity, fame, commemoration. This lexicon — reading, shade, categories, houses, mothers, and realness — are not ethereal, general abstractions but lived, embodied, and coded terms for survival strategies. Not just ideas, these words animate queer people in particular, culturally-specific, and relational positions to move, to perform, to act, to live. By visualizing these concepts as vocabulary lessons, and by including footage with instructions for their performance (e.g. Willi Ninja's lessons on vogueing), these acts can be conducted and performed by an audience member outside of the communities being filmed. In this way, queerness both proliferates in unpredictable directions and consolidates around particular terms. New ways of being queer emerge, animated by old words made new through embodiment.

Body/Text

Queerness, as mediated by the RuPaul's Drag Race corpus, is further figured through the unstable and uneven conjuncture of text and body, interpretation and movement, performance and presence. Dana Luciano, in a wonderful introduction to an ASAP/J cluster on "Queer(s) Reading," says that queer reading can make us attuned to the "enmeshment of text and body."5 It foregrounds the reading of the (queer) body — their readings of and their being read by others. It opens up avenues for what reading can look like and how it can be performed, albeit within a formula. Most notably, or at least most widely (ab)used is its concept of reading. RuPaul's Drag Race provides not only product, but also method, teaching audiences how to consume branded, palatable queer content.

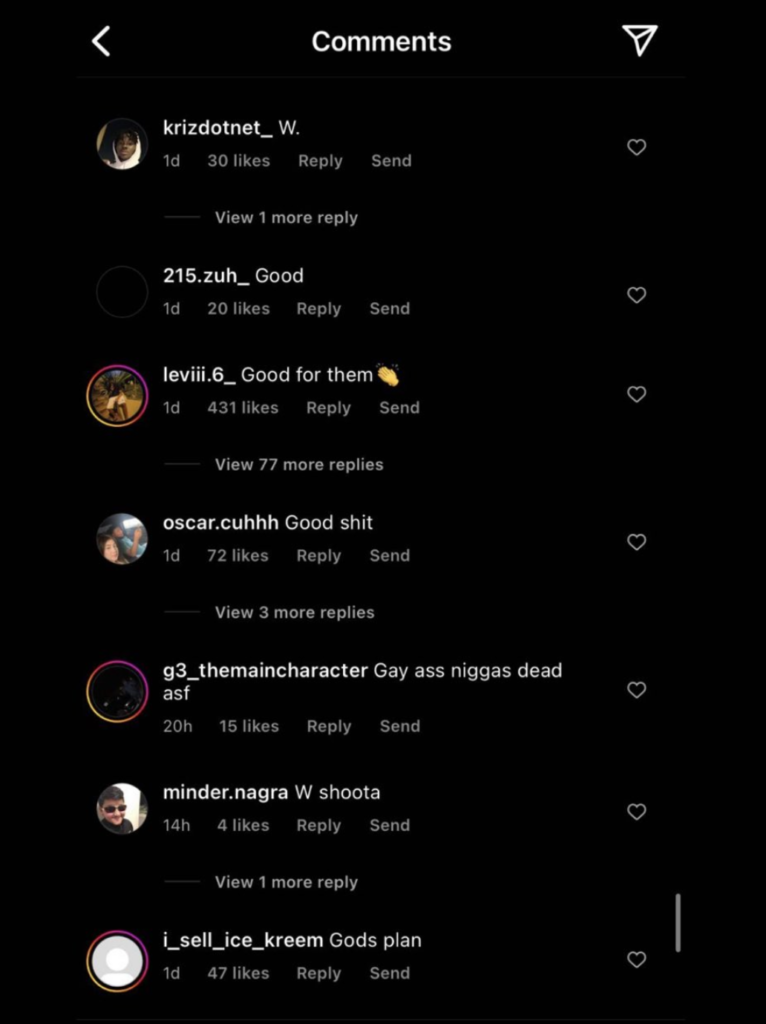

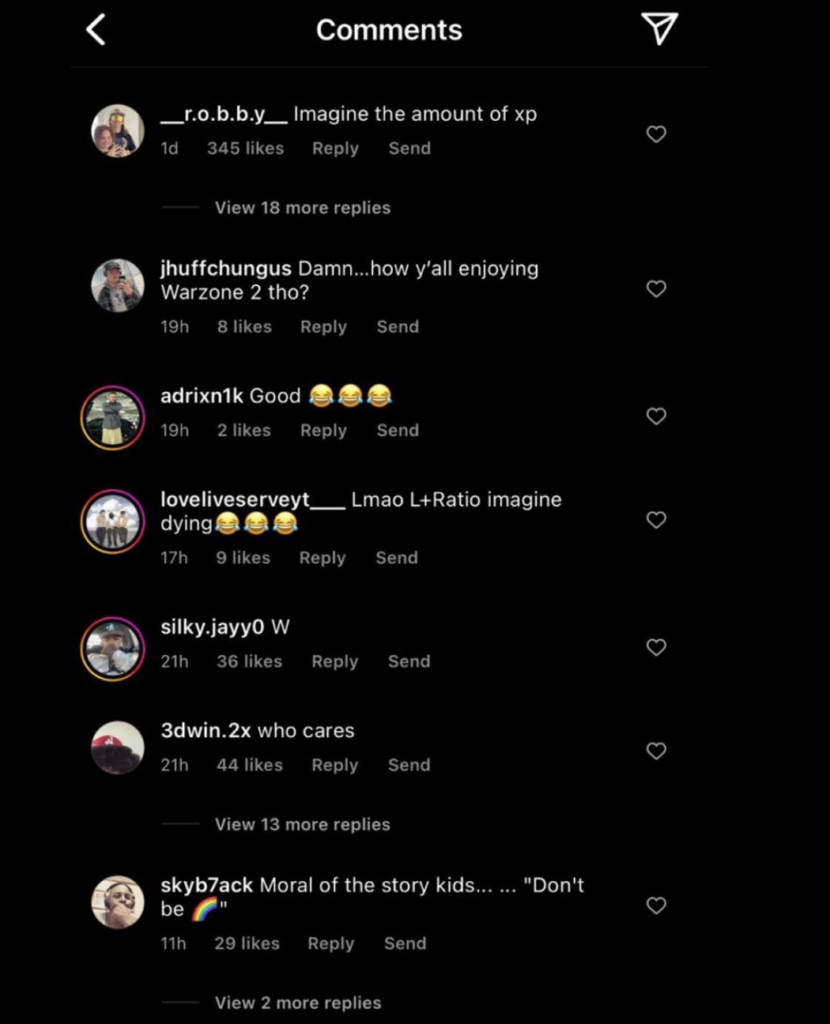

Effectively, the show aspires to provide viewers lessons on reading queerness — as mediated. It knows that many encounters with queerness in the flesh are mediated by the figures and metaphors which represent queerness. It has a self-declared responsibility — "to educate America" — about how to encounter (read) queerness, and to understand it as layered. We write this cluster at a time in the United States where people celebrate or otherwise attempt to justify the murder of queer people; online comments about the Club Q shooting reveal a segment of the populace reacting as though their homophobia had been vindicated, as screenshots from a recent Instagram post by The New York Times suggest:

Indeed, we write in a context where "drag queen story hour" is represented as one of the premier threats to children — more than precarity or poverty, more than school shootings and legislative inaction, more than conversion therapy, and even more than the ongoing catastrophes of global climate change, racial and gender-based violence, environmental injustice, and an unending pandemic which continues to highlight inequities between communities.6 Drag queens are used as a scapegoat in utterly false and dangerous right-wing talking points about "grooming," in the context of state surveillance and state-sanctioned violence, where the diversity of queer experience is subsumed under a general deviance that sees no difference between queer people, trans people, and drag queens, while representing all as generic political villains to further political projects of criminalizing trans and queer people through legislation.7

Much to the fury of people who claim "queerness" is learned, groomed, taught, absorbed or otherwise external to children, and who believe speaking the existence of it is a kind of ideology, it may manifest well before adulthood — and Drag Race knows this. The show is aware that a large segment of its viewership is young queers — and it manifests as much of a "talking-about" queer children as it performs a "talking-to" that audience, as Mary Zaborskis distinguishes in her exploration of the show's relationship with childhood in this cluster. Then again, that all the queens enter the competition as queer — up until Maddy Morphosis walks into the Werk Room — means that other parts of their identity and experience can emerge, giving life and vitality to queerness as embodied, morphing, and surviving. In its more explicit pedagogical moments (e.g. RuPaul relaying histories about disco music, dancing, or divas), RuPaul's Drag Race foregrounds its role as an aesthetic education in queerness.

Reading itself, of course, serves many different functions in the show, most notably in the "Reading Challenge." RuPaul invokes Paris Is Burning at the beginning of every Reading Challenge. This mini-challenge requires the queens to throw shade at one another; the winning queen is she who can outwit the other contestants with clever bits, insults, and ripostes. Reading in its capacious forms has, indeed, also been a survival strategy for queer people. In the beautiful "Notes on Shade," C. Namwali Serpell describes the "practice of reading" — which "also goes by the name of shade" — as "an art of the bookless" with specifically Black and femme origins. Serpell draws on a scene from Zora Neale Hurston's Dust Tracks on a Road (1942) to explain what she means:

The bookless may have difficulty in reading a paragraph in a newspaper, but when they get down to "playing the dozens" they have no equal in America, and, I'd risk a sizable bet, in the whole world.8

Queens like JuJuBee come to be known for their incisive reads in this challenge (and throughout the seasons). Most recently, RuPaul's invocation begins: "In the grand tradition of the legendary documentary Paris Is Burning . . . " RuPaul opens the library with a call and response. "Because reading is what — ?" RuPaul asks. " — Fundamental!" the queens all shout together. What we can imagine as drag exists outside of Paris Is Burning (and even inside of it, the lives of those documented more than what was captured by the camera, insofar as those featured in the documentary are more than — in excess of — what is being represented).9 RuPaul's Drag Race, however, draws a specific genealogy between what it's doing, and Paris Is Burning as an originary, or influential text, honored through Ru's citational speech act commemorating its legacy. One of bell hooks's main critiques of Paris Is Burning is that it claims to portray a "truth," but for a white audience (i.e. how it is that Jennie Livingston can be said to be "just recording" and not affecting the camera's subjects).10

hooks is trying to get readers to understand that the way of life performed ambivalently in Paris Is Burning is itself a "fantasy" of a single point of view, a fantasy constructed to appear as though what the camera cuts is the only reality. hooks cites Dorian Corey's musings on fantasy/celebrity and how one must "return to the real" to live authentically, but what do we do if everything is a fantasy? The fantasies and craft of self-making, of crafting a life, is explored in this cluster in a dialogue on making drag, or of drag being made: Monica Huerta interviews Brittany Lynn, the "Don of Philly's Drag Mafia," to think through the intertwining of drag, fantasy, production, consumption. As hooks asks us to think about, there are several layers of mediation between even Dorian Corey's "lessons" in celebrity and reading narrated over scenes of Venus Xtravaganza and others reading in Paris is Burning, and Ru's "lesson" for queens on a show she's produced to replicate in franchises across the globe. In a recent episode of UNHhhh, Trixie and Katya distinguish between reading that is "more like Drag Race" with the implication that there are also other — and better — instances that maybe cameras will never catch.

Which is maybe one reason why Sophie Chamas's articulation, in this cluster, of an "ambivalent" reading practice for the show is so productive. Chamas sees ambivalence as an ongoing mode of engagement, "rather than feeling the need to either uncritically celebrate or categorically denounce it," and explores the show's ripples in Beirut's drag scene by thinking alongside two Lebanese queens: Latiza Bombé and Anissa Krana, whose video essays accompany Chamas's piece. This queer ambivalence of reading on Drag Race functions as: remediated vernacular; inspiration for a mini-challenge; the source of conflict between queens; the line-reading of scripts; or a way of noticing and viewing ("reading the room" or "reading body language").

Reading also functions in the act of commemoration that usually begins each episode: the eliminated queens have left a lipstick trace of themselves in a farewell message on a mirror that the remaining queens read at the beginning of the episode, a citation of Elizabeth Taylor elegantly, furiously, and flourishingly writing "No Sale" in BUtterfield 8 (1960), using her lipstick as a marker and tracing it on the mirror rather than applying it to herself. The Werk Room itself is a massive dressing room bathed in fluorescents and neons with popping, vibrant purples and pinks bouncing from face-mirrors to hand-mirrors to full-length mirrors to television screens and to the eyes of contestants and editors and judges and audience members from heterogeneous readerly backgrounds. Reading might happen here, but The Werk Room is also where queens brace themselves for the possibility of being "read" on the runway.

Reveal/Reveil

Reading functions in the aesthetic judgments about runway looks and challenge performances by and from queens, judges, and even the larger viewing audience. In their runways, queens turn "looks," which is effectively a fantasy the queens have chosen to embody: the queens feel their fantasy so the audience can feel it through them. A look, after all, is more than just clothing. It is the "beat face" — a face made-up with make-up, which can foreground color and vibrancy, blend with, or even create facial features like cheek bones, jaws, cheeks, foreheads, eyebrows; it is used to paint lines, form shapes, trace narrative contours or further dissolve them — clarifying and/or confusing. Looks are also the jewelry. Earrings and necklaces and bracelets and other kinds of ornaments which fabricate details into the look, and into its meanings. It is also, of course, about the hair, flowing or contained, or spiked, or bouncing, or woven, or high as heaven. (Anything is possible after wigs fly; wigs which are in this way simply another kind of supplement for hair loss.) The look also involves attitude and the performing body's movements and whether they are accentuated or obstructed by clothing. The look is object and objective, or objection, depending on how the judges feel about it. Sometimes even a failed performance in the maxi-challenge can be compensated by turning a solid look. The look can be salvation — or damnation, if the look fails to impress, or if it falls apart during the walk, or if it limits movements during a lipsync.

The body to be read and the body of the reader meet on the runway. Drag Race foregrounds the importance of reading in its competition and in its form; often, being with queerness (or, at least, consuming it) means sitting with joy as much as cringe, with playfulness as much as unease and ambivalence, excess, extra. This is a performance of the promise that there is always more to come, a juxtaposition of citations and metaphors and imagery and dress and composition. The look as the body/text is further mediated by stage lighting during a runway walk. Lighting that highlights as much as it understates. In "Poetry Is Not a Luxury," Audre Lorde argues the "quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live" — and makes clear her metaphor: "This is poetry as illumination." Lorde's extended metaphor is a guiding light that implicates illumination as a montage of light and dark. To shed light may cast shadows, and poetry is a way to contain in form a specific view, or perspective, a mingling of light-waves and colors and hues and shades and shadows and invisibilities. Lorde calls us to cast this illumination on the unseen and unspoken inside of us: the "deep places" that are "ancient and hidden" which contain feelings that are yet "nameless and formless."11 To turn, to re-turn (Ru-turn?) is to expose new possible ways of viewing a thing, yet to then conceal old views of it. To make new, to alter (before the altar). There is no light which reveals all, shows all, tells of every perspective and possible reading. To represent is to re-present — to Ru-present — something from a new angle, perspective, form, focal point, medium. In re-presenting meaning, these metaphors reveal as much as they reveil: cover, warp, obscure, distort, disavow, pollute, eject, hide — shade.

The show, in parts, glances and stares and watches and looks away from the look to complicate and unsettle associations of commensurability between sight with knowledge: of seeing as knowing, and of being seen as being known. To cast new illuminations and revel in new shades and shadows around, beyond, through, on, inside, and upon by (re-)turning (to) the look. Positioning itself as pedagogical, in the vein of Paris Is Burning, RuPaul's Drag Race provides viewers lessons in how to consume a kind of co-opted queerness. Drag Race frames for its audience a method for reading queerness — or queer reading — along with examples, and a lexicon and grammars which order the chaos of queering into a structure of language. RuPaul, along with the World of Wonder producers, are, in Ru's words, "devotees of Andy Warhol" — holding as sacred what on other altars would be called the sacrilegious.

A momentary stare at a queer someone turning looks, serving face, giving body-ody-ody on the stage. It was though they had been lowered into my life from the firmament. The chorus in my ribcage sang while the queen danced above the stage, like the flight of gods or heroes, but not quite — and even better. Deus ex machina, or: a god, enabled. Truth from artifice. Truth in duplicity. Desperate for salvation, I wanted to stretch my hands toward her in prayer, and in between my fingers trace hallelujahs with dollar bills (that's just drag etiquette). This was queerness alive and expressed as an uneasy, impossible parsing of performance from performer. My own vision of queerness, began to crack before the stage, this scene, and the chorus in my chest mourned the splits with a reprieve in the form of actual, tangible, embodied hope. I swelled in confidence, and met with kindness a self I'd written off as damned and doomed. Which is so, but not only. What is queerness if not discomfort, unease, excess, all that extra stuff? Through the show and its lineage I see there was always a vision before me, after me, around me, inside of me: seductive, playful, enrapturing scenes of gorgeous, special, queer life, living.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to the Princeton University Humanities Council and Emory University's Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry for sponsoring our cluster and making all of this possible.

References

- Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).[⤒]

- Chen, Animacies, 64.[⤒]

- Aren Z. Aizura, Mobile Subjects: Transnational Imaginaries of Gender Reassignment (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 3.[⤒]

- E. Patrick Johnson, "'Quare' studies, or (almost) everything I know about queer studies I learned from my grandmother," Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 126-127.[⤒]

- Dana Luciano, "Introduction," ASAP/J, Queer(s) Reading cluster, May 31, 2021. https://asapjournal.com/queers-reading-1-introduction-dana-luciano/.[⤒]

- Jon Freeman, "Tennessee Wants to Criminalize Drag Shows. Welcome to the Right's Latest Assault on LGBTQ People," Rolling Stones, December 8, 2022. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/drag-shows-illegal-tennessee-bill-1234641834/.[⤒]

- Erin Reed, "Texas Just Tried To Get A List Of All Trans People. Other States Consider Registries," Substack, December 14, 2022. https://erininthemorn.substack.com/p/texas-just-tried-to-get-a-list-of. See also: Human Rights Campaign, "Unprecedented Onslaught of State Legislation Targeting Transgender Americans," https://www.hrc.org/resources/unprecedented-onslaught-of-state-legislation-targeting-transgender-american.[⤒]

- C. Namwali Serpell, "Notes on Shade," Post45. Formalism Unbound, Part 2, 5 (January 2021). https://post45.org/2021/01/serpell-notes-on-shade/.[⤒]

- Marcos S. Gonsalez, "Speculating on Queer Pasts to Achieve a Queer Eternity for My Tío Cano," Catapult, June 3, 2019. https://catapult.co/stories/queer-pasts-speculation-history-paris-is-burning-legacy-marcos-santiago-gonsalez.[⤒]

- bell hooks, "Is Paris Burning?" in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Routledge, 2nd ed, 2004).[⤒]

- Audre Lorde, "Poetry Is Not a Luxury," Sister, Outsider: Essays & Speeches by Audre Lorde (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984), 36-39.[⤒]