The Hallyu Project

When it comes to the worldwide significance of Korean popular culture right now, the seven-member group BTS (or, 방탄소년단) naturally comes to mind — they are, by almost every measure, one of the most popular musical artists on earth. BTS grew slowly but consistently from debut underdogs in 2013, backed by newcomer management company BigHit, through a series of record-smashing "firsts," including toppling world records previously set by Queen and The Beatles. They were also the first Korean artists to receive both Gold and later Platinum certifications from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), as well as the first to top the Billboard 200, Hot 100, and Global 200 charts respectively. Within South Korea, BTS are the best-selling artists of all time and hold the title of best-selling album of all time with Map of the Soul: 7. The fact that the group achieved their unexpected rise to fame across the same period global audiences were simultaneously engaging with a fresh wave of Korean media is no coincidence. Understood as both participants within and drivers of "Hallyu 2.0," BTS offers critics engaging with these cultural movement(s) a wealth of opportunities. However, the group's personal experiences of their success are far more complex than any laudatory recitation of the facts.

Within their career, a particularly pivotal moment occurred at the 2018 Mnet Asian Music Awards in Hong Kong, as the members accepted their third and final grand prize of the night for Artist of the Year. The award marked the culmination of a whirlwind twelve months — which featured milestones such as speaking at the United Nations, inclusion as a TIME Magazine Next Generation Leader, reception of a Hwagwan Order of Cultural Merit, and the renewal of their label contracts for another seven years. The near-sweep of grand prizes drew an intense, emotional response from the artists. "Seriously, this award,1" said Jung Hoseok — and then, he paused. His smile wavered. Over fourteen grimacing, silent, broadcast seconds he struggled to continue before ultimately bursting into tears. For an entire minute, the members clustered around him while he wept. Eventually, he managed to say, "I think I would have cried with or without this prize this year." The real shock came, however, when Kim Seokjin announced the group had seriously considered disbanding at what seemed to be the height of their success due to the pressure. The outpouring of grief and gratitude from BTS was almost too painfully intimate to witness, and made abruptly visible the psychic costs of their unprecedented tier of fame.2

This brings me to their first studio album released following this period of uncertainty, Map of the Soul: 7 (2020) — an album that centers on those deeply-felt experiences, marking a new direction for the group. Alongside its visual/performance materials,3 the nineteen-track album stands as a reflection on (or, "confession" of4) the band's previous seven years. It also serves as a "reboot"5 for their creative trajectory and vision. Sonically and conceptually ambitious, MOTS:7 weaves solo tracks among full and partial group songs; its stylistic range traverses from pop, to hip-hop, to R&B while synthesizing additional influences from several genres including trap, EDM, and contemporary rock. . Initial promotional activities, such as a performance of "ON" at Grand Central Station, gave every indication that MOTS:7 would be ground-breaking at home and abroad — until lockdowns for COVID-19 began less than two weeks later.

During the pandemic years, broader audiences than ever seemed to engage with Korean popular culture, including the work of BTS, whose upward trajectory has continued without rest. However, despite the release of several more albums since, I never quite stopped thinking about the significance of Map of the Soul: 7—not only for the band, but also as a cultural text.

+ + +

I've been a fan of BTS since 2016, an on-the-ground witness of their rise to superstardom. Initially, this long-term engagement made choosing a single focal point for an essay wildly difficult. The sheer amount of material associated with BTS, both as artists and as major figures within K-pop as a cultural export, could spark examinations ranging from how gender and desire function as part of Hallyu across the queer transnational to the group's economic impacts on global tourism to South Korea.6 However, it was precisely this sensation of overwhelm — an emotional state arising from my own memories of and relationship to the group — that led my scholarly interest back around to the affective dimensions of their art.

What I mean by affects are those felt emotions and bodily intensities "arising in the midst of in-between-ness: in the capacities to act and be acted upon ..., in those resonances that circulate about, between, and sometimes stick to bodies and worlds."7 I draw from the ways theorists such as Ann Cvetkovich and José Esteban Muñoz frame the practice of studying feelings themselves as meaningful ephemera, but also from their insistence that affects are neither neutral nor autonomous. Rather, affects are relational — meaning they arise from and create the inseparable interconnectedness of peoples, places, objects, animals, media, and worlds. The bonds crafted between idol groups and their fans, for example the closeness I feel with BTS, rely on a sense or perception of reciprocity: an emotional intimacy between artist and audience produced through performances and cultural objects. While a discussion of these parasocial relationships as purely circulating market commodities within idol fandom, or even Hallyu more broadly, is possible, without a consideration of the sticky attachments and feelings that drive that cultural circulation, an entire layer is absent from critical constructions of the phenomenon itself.

Additionally, focusing on an album pushes back against a tendency to discuss BTS as a phenomenon — a trend of engaging primarily with their large fandom or numerical measures of their popularity as opposed to their creative work. While focusing on BTS as a trend may come from a place of positive intent, its implications as a pattern within the treatment of Asian identities and cultures troubles me. As Patty Ahn argues in Aftermarkets of Empire, "US racial imaginaries" always inflect assumptions about the "manufactured" versus the "authentic" within K-pop, alongside a related "fascination with the exotic."8 Mythologies of techno-orientalism and the trope of the Asian artist as a mechanical conduit, one who merely performs, float through much mainstream US. response to BTS.9 I need only gesture to their treatment by the Recording Academy, an institution regularly critiqued for its racist practices.10 Grammy nominations for "Best Performance," while their albums and songs are dismissed, coincide with their deployment as ultrahyped broadcast headliners required to negotiate repetitious jokes about their language skills on live television, while receiving no awards.

What draws me to MOTS:7, therefore, is a desire to treat the text as both an album and what Anne Cvetkovich refers to as an "affect archive."11 MOTS:7 engages deeply with BTS's ambivalent experiences of fame, providing a textual space for the artists to mediate conflicts between expectations of un-manufactured authenticity — a vexed and ever-shifting target demanding intimate, vulnerable, or spontaneous "realness" — and simultaneous expectations of high caliber, meticulously crafted performances perceived to be representative of South Korea. I want to turn away from external or merely surface considerations of the properties and influences of BTS through Hallyu to an internal, reflexive positionality focused on felt experiences — for fans like myself, but more importantly, for the artists involved. This shift in focus layers emotional texture beneath ongoing debates around the "historical and industrial imperatives [that] drive the Korean music industry to work so actively to re-imagine Korea, and Korean music, as 'global'" (Ahn 3), turning to consider the human experiences beneath and within this cultural movement.

Or, put another way: how does Hallyu feel for Korean artists caught up within it, and what critiques or understandings can then be drawn from their creative processing of those feelings? Reading the "content of [cultural] texts [as well as] the practices that surround their production and reception . . . as repositories of feelings and emotions" (7) is necessary when centering affect as a critical lens. For example, what "compelling descriptions" of the affective disruption caused by immense transnational fame does MOTS:7 present to disparate audiences — fans, critics, other Korean artists, the unfamiliar listener whose Spotify algorithm delivers them an album recommendation — as the members of BTS use the album's tracks and overall sonic arc to dramatize personal, nuanced, often unpleasant reflections on the prior seven years of their career?12

To answer the question: what emerges from these complicated, collected affects is a deep ambivalence regarding the entire experience of being Korean superstars consumed at a worldwide scale. On the one hand, within the genre context of K-pop, it is uncommon for artists to register complaint with regards to their fandoms, their fame, or the knowledge that their performances contribute toward the soft power of Korean culture industries on the global stage. On the other hand, MOTS:7 doesn't stop at registering complaint. The album has no interest in firmly settling whether the group's experiences within Hallyu have been purely good or purely bad. Rather, the text negotiates a third space: one where the inherent political and personal complexities of being consumed by global audiences as Korean artists, and thereby always in part as cultural representatives, can be presented with an emotional depth that resists broader simplifications.

+ + +

Though analyzing each track on MOTS:7 and its associated performances would be engaging, four songs are capable of representing the whole for my purposes. The primary singles, "ON" and "Black Swan," wrestle with the intense pressure of worldwide fame and how BTS perceive their own collective artistry within it. However, the album also contains twelve single member or small-group tracks, each of which engages on a closer personal tier with the circulation and attachment of relational intimacies between artists, audiences, and industry. At the same time, songs like "Shadow" and "Filter" explore how complicated the members' feelings about constructing a revealing, emotional performance can be — while, simultaneously, doing exactly that.

On January 17th 2020, "Black Swan" was released on YouTube through an "art film" performed by the Slovenia-based MN Dance Company[1] as opposed to a traditional music video. The song traces the process of creation under a global spotlight, fear of losing connection to one's art, and recommitment to the process despite the struggle.13 The film opens on the Martha Graham quote, "a dancer dies twice — once when they stop dancing, and this first death is the more painful," before fading onto a long shot of the seven European dancers whose white bodies stand in for BTS. An orchestral score emotionally accompanies the film as one shirtless, contorting dancer is buoyed, restrained, brutalized, chased, and ultimately supported by six clothed dancers; these pictures also reoccur in future BTS live choreography performances. As Ahn has shown, performance elements of K-pop as they appear in music videos and dance choreography animate the narrative and emotional content of a song's lyrics. For casual audiences outside of Korea, who do not possess facility with the language, bodily performance communicates the emotional textures of the composition, encouraging "an affective connection with artists" that might otherwise be missed.14

Two notable aspects of this release are the purposeful engagement of what the average Western audience would recognize as "the fine arts" and the fact that BTS do not appear within the music video, a startling shift from genre norms. From this presentation of cultural hybridity — a Korean language song dramatizing artistic creation and the constant stress of being read by global eyes overlayed on an orchestral score and accompanied by a contemporary dance troupe — perhaps emerges an insistence that BTS be understood as in conversation with, and requiring no less serious consideration than, other artists on the global stage.

However, while "Black Swan" constructs BTS as artists engaged in the studio composition process — challenging aforementioned biases regarding Korean popular musicians as "mere performers" — it also emphasizes the oceanic pressure of expectation that comes along with global consumption. Kim Namjoon's melodic rap frames their creative process in the same terms as the Martha Graham line opening the art film, in Korean:

이게 나를 더 못 울린다면

내 가슴을 더 떨리게 못 한다면

어쩜 이렇게 한 번 죽겠지 아마

(If this can no longer resonate

No longer make my heart vibrate

Then like this may be how I die my first death)

But what if that moment's right now, right now

The chorus, which alternates between "film it now" and "killing me now," gestures to the agonies of being constantly observed as they struggle to perform, create, and survive. While the last verse refuses the drowning sea of doubt and lack of inspiration, the closing chorus then eerily returns in the echoes — implicitly continuing the cycle of pressure, uncertainty, and renewal. What are a set of artists to do, then, after agreeing to continue despite the costs?

Craft a manifesto — or, refuse manifestos altogether.

On February 21st, the album dropped alongside "'ON' Kinetic Manifesto Film: Come Prima," with the "'ON' Commentary Film: Dialogue" following the next day.15 The subtitle Come Prima translates to "in the same way as the first time," or back to the start. Manifestos are generally textual objects presented at a distance from the artists, but BTS instead construct a "kinetic film" that combines audiovisual elements with the physicality of their performing, feeling bodies — visually returned to the screen after their absence from "Black Swan." And, unlike that contemporary dance film, this manifesto takes the form of a traditional K-pop group performance, as if shifting from internal conflicts around being read on the global stage to an embrace of their own multifaceted roles as composers, producers, and performers.

The music video opens on a group of dancers in similar black clubwear outfits spread over a stretch of sun-washed concrete. Then, the pounding beat of the song erupts as the dancers mime militant drumming. The members of BTS weave through the dancers' formations as they deliver both individual and group lines, staring with confident demand straight into the camera lens. Their monochrome outfits reveal flashes of bicep, nipple, and belly as they perform elaborate, intensely physical choreography. I would describe "ON" as teeth-bared music, and the visual performance adds to that powerful texture — providing the audience with a necessary "sensorial thrill"—by demonstrating an outsized, sweaty, bodily effort that matches and amplifies the merely auditory intensity of the song by itself.16 The lyrics combine a frank, aggressive recommitment to art with deeply ambivalent acknowledgement of the ongoing costs of worldwide fame.17

Once again traversing between languages while employing their moving bodies as secondary translation, their kinetic manifesto rides on the central chorus:

미치지 않으려면 미쳐야 해

나를 다 던져 이 두 쪽 세상에

Can't hold me down cuz you know I'm a fighter

제 발로 들어온 아름다운 감옥

Gotta go insane to stay sane

Throw myself whole into both worlds

Can't hold me down cuz you know I'm a fighter

Carried myself into this beautiful prison

Find me and I'm gonna live with you

가져와 [bring it] bring the pain, oh yeah

올라타봐 [ride on] bring the pain, oh yeah

The recurring phrase "gotta go insane to stay sane" — translated as "to remain sane, one must go insane" — echoes a phrase from Lauren Berlant. Berlant argues that "genre flailing" within contemporary cultural production acts as a form of "crisis management," a method for dealing with the disruptive or negative affects that arise when a person's life-world "becomes disturbed in a way that intrudes on one's confidence about how to move in it," the same disturbance that MOTS:7 dramatizes in its explorations of the pressures of transnational fame. Berlant continues, "We genre flail so that we don't fall through the cracks of heightened affective noise into despair, suicide, or psychosis. We improvise like crazy, where 'like crazy' is a little too non-metaphorical."18 Reading MOTS:7 with its disparate modalities, musical styles, lyrical compositions, and cultural contexts through the lens of the genre flail opens a deeper understanding of the album as a survival mechanism. The contents of the album are, of course, individual to BTS — but invite further conversation on the systemic difficulties encountered, to some extent, by other Korean artists also engaged in globalized cultural circulation: wrestling with ongoing tensions between "the local and the global," dealing with the psychic weight of Western consumption and appropriation, and adapting to shifting transnational industry standards across the decade of the 2010s, to suggest a few.

BTS may have, in their own terms, "carried themselves" into a "beautiful prison" — one that comes with hypervisibility and an intense, relentless pressure to stand as solid cultural representatives and global icons (or, idols). But despite the stressors, with the lyric "find me and I'm gonna live with you" the song invites continued relational connections between artist and audience. By centering on the emotional experiences of pain, struggle, connection, and desire, then performing them across multiple modalities, the manifesto doubles as an anti-manifesto: a refusal to state any goals beyond that of continuing to do art in the face of global fame's disturbances to their interior worlds.

+ + +

It's worth noting that MOTS:7 consists primarily of sub-unit and solo tracks, a common practice within K-pop as distinct from the majority of Euro-American popular music. Practical stage considerations require that group members rotate rest periods, while the intimacies of idol culture require opportunities for fans to bond with separate members. BTS embraces this compositional structure in their "genre flailing" to astoundingly cohesive ends, using the structure to provide separate stages for each artist. These songs accrete into an affect archive, constructing stories of how not just their group but also individual experiences with transnational fame have felt. As the solo songs fill out the album, so too does their affective content fill out the emotional frame of tracks like "Black Swan" and "ON." The ways BTS craft a sense of emotional intimacy, or even vulnerability, within their art — and reflected in social media — draws from K-pop's distinctive technologies and forms, while at the same time troubling the effects these forms have on the artists themselves.

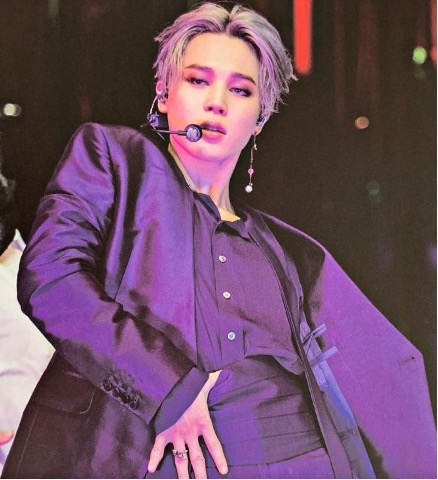

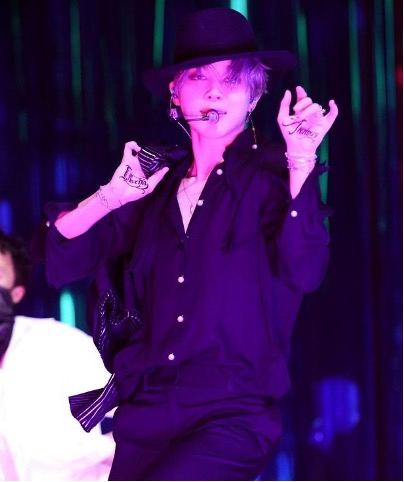

Consider Park Jimin's solo song, "Filter." The lyrics spill over with intensities around eros, desire, and the delights of shapeshifting19 through performance and online consumption, while the choreographed live show dramatizes gender-as-costume. As he sings, the routine sees him seductively draw feminine clothes from a mannequin and don them himself. He then strips again, putting on a masculine outfit provided by the male back-up dancers, before a dramatic quick-change strip to genderfucked purple suiting, hands painted to read "illecebra arcanus." A cloud of glitter surges as his final choreography pulls the audience's cruising eyes down to his crotch.

However, alongside these erotic visuals and lispy, sensual vocals, the self within the lyrics disappears beneath our hungry eyes. There is pleasure to be found in malleability, being able to shift between filters, but "날 골라 쓰면 돼 (you can pick and use one of me)" has eerie, disruptive implications as well. The invitation to use him without regard — while simultaneously being seduced, taken over by a figure whose eros overcomes all "tastes" and "standards" — carries a real uneasiness alongside its proffered intimacies.

Or, consider "Shadow" by Min Yoongi. The lyrics address how it feels for him to arrive at the top of his field — namely, the anxiety, fear, and exhaustion that come alongside becoming "a rap star, a rock star, a king."20 Riding multiple rhythms and flow patterns, Min Yoongi shifts from melodic mumble to pitchy snarl, castigating himself over his ambivalent feelings about getting what he's always wanted. The beats constantly fluctuate, refusing a solid sonic footing to the listener. In the chorus, he repeats that ascending to such towering heights makes him "dizzy," and that "flying high is terrifying" — because the higher he goes, the farther there is to fall.

Meanwhile, the music video filming locations are an anonymous hotel with grotesque, smeared walls and a translucent stage where threatening hands press up from beneath while audiences ahead film on their phones. One specific picture powerfully dramatizes the affective core of the track. A crowd of faceless, pursuing hands grabs Min Yoongi's shoulders to force him down to his knees as the lyrics oppositionally rasp, "I rise, rise, I hate it" — while onscreen he gives a soft, exhausted sigh of acceptance, or perhaps acquiescence. The dissonance between the visual performance and the rap verse illustrates the anxieties he personally feels around their atmospheric rise. Contrasted with "ON," which presents group anxieties about pressure and fame as part of their committed and aggressive manifesto, "Shadow" shifts the frame to an unresolved, internal conflict about endless observation and consumption that lies behind their collected whole.

These two tracks represent a fraction of the whole — but all of the solo tracks carry a profound sense of ambivalence regarding their global endeavors. Or, from another angle: a sense of disidentification. Per José Esteban Muñoz, whose critical work explores relationships between queerness, racialization, and performance, the practice of disidentification adopts then "scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of [majority] cultural texts." By translating and "recircuiting" those cultural materials, such as the contemporary dance of the "Black Swan" art film or the gender-transgressive erotic performance of "Filter," artists such as BTS are able to expose the "universalizing and exclusionary machinations" of culture industries — at home, abroad, and also in the messy spaces between — in ways that "account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications."21 The third space BTS have come to occupy as artists refuses wholesale endorsement or rejection of either the K-pop industry or the U.S. American pop industry, simultaneously critical of and participating within each.

In the summer of 2022, BTS announced through an hour-long livestream the closure of "chapter one" of their career as young male idols, clarifying that this would be the beginning of "chapter two" — devoted to focus on individual creative works as well as full adult lives, both within and outside the public eye, less dictated by the restrictive norms of entertainment industries. This opening (not closing) gesture shows how Hallyu influences and is critiqued by artists caught up within it, and a fuller picture of this cultural moment and its affordances — as well as its costs — emerges. What is therefore revealed by Map of the Soul: 7 as an affect archive, an inflection point, and an act of disidentification is a nuanced portrait of how BTS themselves have negotiated the pressures of their role as Korean popular artists riding the "second wave" across a global stage complexly mediated by race, nation, and language, and perhaps more importantly, how they felt about it.

Lee Mandelo (he/they) (@leemandelo) is a doctoral candidate in the Gender Studies department at the University of Kentucky whose work has recently appeared in Capacious, GLQ, and Signs. He is also a fiction writer, critic, and occasional editor; his debut novel Summer Sons, a contemporary gay southern gothic, is soon to be followed by a near-future sf novella, Feed Them Silence.

References

- For the most part I use official subtitles. However, earlier BangtanTV episodes were never subtitled, so fans relied on channels such as Bangtan Subs or Twitter accounts to translate. Later releases, such as those on the Memories of 2018 DVDs, contain subtitles but also edited footage. Therefore, where appropriate, I draw from fan translations to provide additional context.

[⤒]

- "BTS (방탄소년단) @2018 MAMA in HONG KONG." YouTube, uploaded by BANGTANTV, 18 May 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wkv2zRPef8E.[⤒]

- Including music videos and short films; album packaging; the Break the Silence docu-series; and behind-the-scenes production livestreams.[⤒]

- Kim Seokjin, as reported in a press conference translation by Vogue UK.[⤒]

- Kim Namjoon, interviewed by Variety. He goes on to say the guiding principle was to "reflect [on] ourselves and figure out ourselves again: Where are we? What are we doing? Who were we in the past? And [who are we] right now?"[⤒]

- See Patty Ahn's Aftermarkets of Empire, on the "alternative spaces of desire" offered by K-pop to those "who feel alienated and queer within heterosexual spaces of music culture" (136). With BTS, one might consider their extensive collaborations with queer musicians, circulation of queer arts in public conversations, and gender-expansive lyrical/visual presentations.[⤒]

- Gregory Seigworth and Melissa Gregg. The Affect Theory Reader (Duke University Press, 2010).[⤒]

- Ahn, 5.[⤒]

- See Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media, eds. David S. Roh, Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu (Rutgers University Press, 2015).[⤒]

- See critiques by Tyler the Creator and The Weeknd, alongside countless others from Black artists.[⤒]

- Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feeling: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke University Press: Durham, 2003), 7.[⤒]

- Ann Cvetkovich in Depression: A Public Feeling suggests "performative writing," which embraces how bad feelings feel, lends itself to dealing with disruptive experiences.[⤒]

- For a translation of the video's lyrics, see https://doolsetbangtan.wordpress.com/2020/01/17/black-swan/.[⤒]

- Ahn, 4.[⤒]

- The documentary also features dialogues with the predominantly Black American artists, engineers, and performers whose labor goes into creating a large studio album, emphasizing the cultural hybridity of collaborations between "Korean and Black artists [that] do the work of naming . . . historical and cultural connections" (Ahn).[⤒]

- Ahn, 4.[⤒]

- See translation, https://doolsetbangtan.wordpress.com/2020/02/21/on/.[⤒]

- Lauren Berlant, "Genre Flailing," Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1, no. 2 (2018): 157.[⤒]

- See translation, https://doolsetbangtan.wordpress.com/2020/02/21/filter/.[⤒]

- See translation, https://doolsetbangtan.wordpress.com/2020/01/09/interlude-shadow/.[⤒]

- See Disidentifications, 31.[⤒]