The Hallyu Project

The unexpected success of the Netflix-financed serial Squid Game in September 2021, written and directed by South Korean filmmaker Hwang Dong-Hyuk, undoubtedly confirmed a rising interest in hallyu. While Squid Game's popularity and edgy plot made headlines and topped streaming lists in Netflix's many media markets, it's hard to pin down what audiences "saw" in the series. Assessments of the show were especially divergent in South Korean media, as compared to the North American reception, where it was mostly touted for its viral popularity. In particular, Korean feminists were a vocal subset of the show's detractors at home. As Do Own Kim notes, they decried what they saw as the show's misogynist treatment of its female characters, especially the foul-mouthed Mi-nyeo (a name that functions as both proper noun and ironic label, as the word translates to "pretty woman").1 Reading the show through the lens of generational divides, newspaper media critic We Keun-woo deemed the show a paean to mediocre, self-pitying middle-aged men.2 These gender critiques spoke back to the local media's ethno-nationalist celebration of the show's global (too often a synonym for "Western") reception and consumption.3

In North America, by contrast, fans of South Korean cinema found parallels between the show's blunt indictment of wealth disparity and the social critique mounted by Bong Joon-ho's acclaimed 2019 film Parasite, which swept both art and middle-brow cinema accolades by winning the Palme D'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Oscar for Best Picture in the same year. Korean television serials or "K-Dramas" have been steadily growing international audiences over the last decade and a half, through genres and works often targeting women viewers, like family melodramas, rom-coms, and revisionist or "fusion" sageuk (premodern period costume dramas featuring flower boy royals, time-travel and body-swap fantasy elements, or anachronistic female heroines).4 Yet, in the Netflix/OTT streaming era, Squid Game, Parasite, and other serials in the action-horror vein — Kingdom, Sweet Home, Hellbound, and All of Us are Dead — are said to constitute the new, paradigmatic hallyu corpus, with critics like Jason Jeong declaring that these dystopian, action-oriented works signal "the flourishing of more radical storytelling that confronts the nation's realities" by using "[e]xtremity, in violence, political critique and moral ambiguity" as "the currency of this new wave TV."5 In direct contrast to Jeong's (unconsciously) masculinist point of view, Kayti Burt in Paste magazine roots hallyu's popularity and its difference from Hollywood in its privileging of the desires of women and girls—a market that is often derided in US culture and media. Burt quotes Angela Killoren, CEO of CJ America, who has called K-drama and K-pop "female gaze entertainment."6 Hallyu is now being hailed as a progressive model of global media production, political realism, and cultural diplomacy in the 21st century. For most North American fans, however, hallyu is simply shorthand for Korean culture's visibility in the North American media ecosystem, on account of K-culture's equation with Korean (and, increasingly, Korean American) culture at large. This leads to such disparate works, artists, and viral media phenomena as Squid Game, Parasite, Korean American indie filmmaker Lee Isaac Chung's Minari, writerMin Jin Lee (whose novel Pachinko was adapted into an Apple+ series), K-pop super group BTS, and World Cup 2022 breakout soccer player Cho Gue-Sung being grouped together under its banner.7 With its ever-expanding purview and mutable referents, this unusually labile signifier prompts not only the question, what is hallyu?, but also, in our current context (the North American academy and its adjacent reading publics), who is hallyu for? As a term encompassing media content and reception across many media regions and target audiences, the "what" is impossible to pin down without specifying where and for whom.8

The crossover or mainstreaming of Korean culture in North America — the widespread accessibility of Korean culture-related commodities via the platform infrastructures of our everyday lives, namely, Netflix, Spotify, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Amazon, DoorDash, or Ubereats — confounds existing models of the familiar and foreign. Hallyu seems to promise a social fact that can encompass the coincident appeal of kimchi, galbi, gochujang, finger hearts, and the extreme revenge fantasies that package pop cultural modes of political economic critique in a single, easily digestible concept. In academic discourse, hallyu knits together area studies, media aesthetics, participatory reception, cultural policy, and production practices across sectors and media forms that have at times been theorized in medium-specific terms, yet increasingly converge under a cultural studies heading: cinema, television, comics, gaming, popular music, food, fashion, cosmetics, and sports. However, the boundaries between scholarly, popular, and policy references to hallyu often blur, especially in discussions of soft power and cultural diplomacy. National branding, or the powerful "K" prefix added to hallyu-identifiedsectors, corrals various media institutions, markets, and genres into a unitary signifier of triumphant national development. K-culture for the win. Yet, Korean cultural producers' success in identifying overseas consumer appetites belies a surprisingly conservative socio-cultural environment for creatives, corporations, performers, and policymakers, including broad acceptance of patriarchal-nationalist hierarchies that permeate workplace cultures, even in creative industries, and shore up norms that can strike many in the "west" as sexist, homophobic, or otherwise "backwards." What is behind this paradox?

Many accounts of the growth of Korean commercial film and television in the second half of the twentieth century note the guiding influence of the US, from the partnerships between Korean film studios and American media to expand the domain of "free Asia" during the Cold War to the popular education in American genre cinema, pop music, and culture that "Hollywood kids" like Bong Joon-ho received while growing up in the 60s-80s. In the decades since the signing of the Korean War armistice in 1953, large numbers of US military personnel and the mass media and service infrastructures established to entertain them have materialized the global across South Korean localities. More recently, as South Korean commercial cinema industrialized via home-grown blockbusters, following the Asian financial crisis of 1997, CJ Entertainment and Media (CJ ENM) has emerged as a standard-bearer in the production and distribution of hallyu media. CJ ENM has a large stake in Studio Dragon, the creative enterprise behind several massive Netflix hits, including Crash Landing on You and Extraordinary Attorney Woo. The company's US branch, CJ America, also founded the popular K-Pop fan convention KCON, which is credited with spreading North American K-Pop fandom since its inception in 2012. CJ ENM was established by current Vice Chairwoman Miky (Mi-kyung) Lee, granddaughter of Samsung founder Lee Byung-chul. The rise of KCON and CJ ENM's partnership with Netflix may be a more precise periodization marker for Hallyu 3.0 or "post-hallyu," when the target audience for South Korean media shifted definitively towards "the west." How does this targeting enable South Korean media to in turn reach diverse audiences around the world? By piggybacking on the appeal of the global-as-universal established by American pop culture and media? How does deciphering hallyu help us to understand our attraction to the promise of the global through global media? To what fantasy of legible alterity does hallyu allow us to remain attached?

"Global media" is a tricky term — in many cases, it substitutes for more fraught categories like transnational media and world cinema that are thought to offer exotic spectacle to satisfy cosmopolitan tastes. But, to return to what "global" meant before globalization became a slogan amidst the free-trade utopianism of the 90s, in a word, it meant American. And, for many outside the US and Western Europe, it still does. We should recall that anti-globalization sentiments used to be fueled by fears of cultural dilution via McDonalds and Coca Cola, rather than xenophobic nationalism or catastrophic climate change. Though the scourge of "McDonaldization" was indeed attributed to planetary degradation and worker exploitation by underregulated, multinational corporations, often concerns were most urgently voiced about cultural impacts- — the reshaping of local cultures across the globe into a homogenous America lite. In today's South Korean vernacular, "global" is defined as saegaejeok sujun or "world class," as determined by existing cultural-economic hierarchies of development. "워클," the abbreviated hangulized spelling of "world class," is a label often attached to the likes of BTS and Son Heung-min, the Tottenham Hotspurs striker and most successful Asian player in English Premier League history (who rotated first through the German Bundesliga and confidently gives post-match interviews in German, English, and Korean). In this context, it might seem naïve to celebrate hallyu television as global, since its prominence is directly related to its success and visibility in the US and on American platforms. Netflix, darling of Silicon valley and its platform imperialist ethos, is but a metonym for US techno-power. Is the Korean wave cresting on American shores a sign of Korean culture industries' co-optation by American style corporatism and commodification of culture? Or is it a disruptive form of global media — a global media worthy of the name?

Thinking about hallyu media as a contemporary analog for American entertainment media and as the materialization of what media scholars Bishnupriya Ghosh and Bhaskar Sarkar deem the "global-popular" productively complicates the notion that hallyu merely mimics Hollywood. Ghosh and Sarkar's proposed analytic of the global-popular addresses the simultaneous proliferation of "financial-speculative opportunisms and popular-representation practices" in the era of contemporary globalization, which renders the global as politico-economic hegemony constantly destabilized by the "volatile creatives and intransigent impulses" of the popular. Despite or perhaps because of this conjunctural contradiction, Ghosh and Sarkar note "the rise of the global as the salient aspirational horizon, eclipsing earlier principles of organizing communal affiliations and future visions (civilization, religion, nation)."9

Although Canada is also a "middle power" like South Korea whose media industries battle Hollywood to compete for domestic market share, reactions here to hallyu have been almost indistinguishable from American ones, which suggests a slippage between American, North American, and global Anglophone reception — I use this phrase to refer to the reach of "global English" as a qualifier of flexible, mobile citizens who aspire to be corporate cosmopolitans. This is also the audience to which Netflix appeals10 Various news outlets have sought to explain Squid Game's popularity and South Korea's so-called soft power charm offensive, covering the show as a window into hallyu. The latter remains a perennial mystery for North American publics, despite the steady stream of Korean culture industries successes during the last decade, made all the more conspicuous during the Covid-19 era. Researching reviews and reactions to the show, from the Netflix charts to a subtitling dust-up, led me to a video form that I offer here to illustrate Squid Game's differential reception: the reaction video compilation.

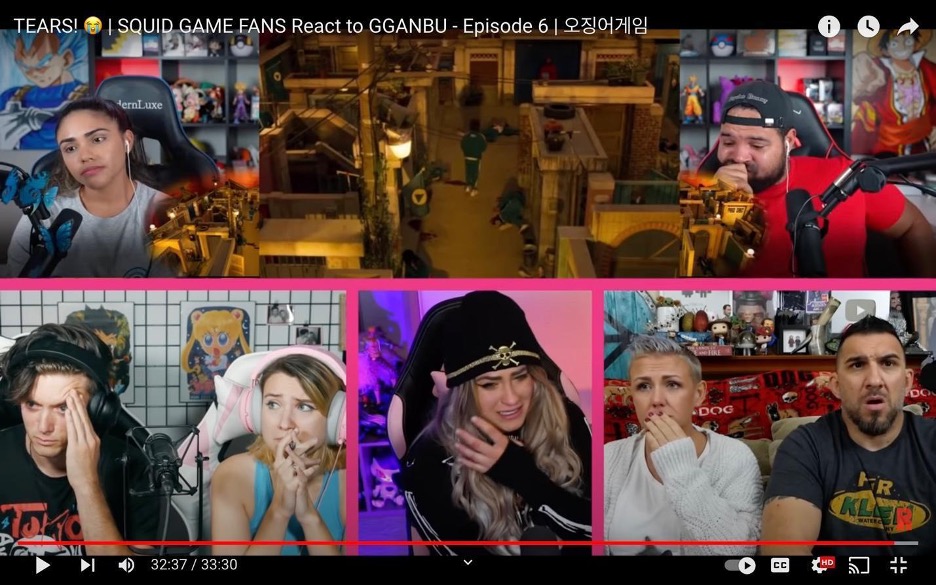

"TEARS! 😭 | SQUID GAME FANS React to GGANBU - Episode 6 | 오징어게임" is a video-edit posted on the YouTube channel "Remixed by Raven."11 The channel's "About" page offers no identifying information except for the uploader's location in Australia — another non-US, Anglophone media market. Video-edits are a key form of fan-produced paratext, usually made and circulated within fan communities. Remixed by Raven's content centers on Anglophone anime fandoms — as indicated by the lack of subtitles offered in other languages or the inclusion of non-English reactors. The channel targets a growing subculture that overlaps with audiences for "Asian extreme," which have grown with the popularity of cult genres like Asian horror (J-Horror, K-Horror), action cinema (wuxia, samurai, and gangster), and sci-fi (mecha) or fantasy anime.12 At roughly 30 minutes long, "TEARS!" assembles clips from other reaction videos to produce a mega-reaction video edit. Through Raven's editorial choices, various clips are sutured together by the form, delivering the semblance of a spontaneous group reaction or a Netflix watch party. Reactors' intent can vary, but since reaction videos are a popular genre of vlog that cannot be monetized through YouTube's content-creator partnership program, vloggers often use them to expand their subscriber bases, to then route these followers to either original, non-reaction content or to alternative subscription platforms like Patreon. But, in the case of reaction video compilation channels, the labor of editing together other people's content is further removed from the entrepreneurial motives of the influencer economy, since the channels lack either monetizable content or an identifiable influencer persona. This places reaction compilations more securely in the sphere of fandom's gift-economy, elevating the affective intimacy of shared spectatorial experience as an end in itself. While the channel produced reaction compilation edits for all of the show's 9 episodes, "TEARS!" is the channel's most popular video, with 763K views as of December 2022.

Squid Game's Episode 6 "Gganbu" is for many viewers the show's most affecting installment. In contrast to other episodes that pit players against the game's designers, "Gganbu" separates players into pairs who must then compete against each other in marble games of their own design. The episode marks a turning point in the show, in which several of the most sympathetic characters in the large ensemble are eliminated. While the show's earlier episodes highlight spectacular and extreme violence within the games, "Gganbu" makes its mark on viewers through intensely melodramatic emotional beats that painfully evacuate the relational high of collective-minded altruism from episode 5. Expecting to once again team up against the faceless evil of the game's designers, each pairing signals hopeful alliance, making the marble games an excruciating abrogation of prosocial bonds. The broken relationships that elicit the most viewer distress in "TEARS!" are those between Sang-woo and Ali, Sae-Byeok and Jiyoung, and Gi-hun and Il-Nam. Ali is an undocumented Pakistani migrant worker who is first abused by his factory boss and then sacrificed to the game by the white collar criminal, Sang-woo. Ali is a figure of preternatural goodness whose betrayal hits the reactors like a suckerpunch. Sae-Byeok is a scrappy, young North Korean defector who joins the game to earn money to pay brokers to bring her mother out of the North and reunite her family. Ji-Young, a South Korean teen who has just been released from prison for killing her abusive father in self-defense, has convinced Sae-Byeok to partner with her, despite both girls being outmatched in terms of physical strength by several of the adult male players. They spend most of the episode bonding over their respective traumas and shared sensibilities until Ji-Young graciously throws the game to save Sae-Byeok. Arguably the most structurally sentimental pairing consists of Gi-Hun, the show's sad sack antihero and laid-off former factory worker turned gambling addict and compulsive liar, and Player 1, an elderly man suffering dementia who later activates the show's most extreme plot reversal. Gi-Hun and Player 1's tender, father-son relationship is tested then restored in this episode, first through Gi-Hun's deception, and then when the feeble old man voluntarily hands over his last marble to Gi-Hun while thanking him for his care.

Like the reactors compiled by "TEARS!," I cried too. Player 1 recalls for me the people most vulnerable to the ravages of the coronavirus, and (as an Asian North American viewer) the elderly Asian victims of random violence during the pandemic. I shed tears for Ali, the Pakistani labor migrant, who represents an exploited population of foreign workers caught in global capitalism's spatial flows, many of whom face xenophobic abuse in a burgeoning multi-ethnic Korea. Affirming humanistic views on multiculturalism in the South Korean media landscape, Ali's archetypical innocence magnetizes viewer sympathy. But Ali's naivete also paints him as a tokenistic figure, even as his fluency in Korean assimilates him. Sae-Byok and Ji-young are marble game opponents but comrades from the perspective of class, gender, and age — young women exploited by the heteropatriarchy that prevails on both sides of the DMZ. What the episode collates are familiar paradigms of social relation to which viewers are strongly if not always consciously attached, which are also activated by personal concerns, local conditions, political issues, discourses, and notable events, which are thoroughly context-dependent. Ghosh and Sarkar call the familiar scripts that shape viewers' attachments — to the bonds of potential besties represented by Saebyok and Jiyoung, to the promises of ride-or-die fraternity in Sang-woo and Ali's story, or to the cosmos-ordering filial piety betrayed by Gi-hun's treatment of Player 1 — "global structures." These scripts fuse narrative, characterization, social category, and emotional response, activating a melodramatic reception context that can serve as a heuristic for mapping cultural conditioning.

"TEARS!" cycles through the climactic end of each of the above pairings, focusing on how each storyline impacts the reactors, many of whom are simultaneously immersed and self-reflexive — indeed, the reaction performance relies on sustaining the tension between these two modes of viewing. Most of the reaction channels featured in the compilation consist of pairs or groups of men and women, who display emotion in conventionally gendered fashion. The women weep while, with few exceptions, the men fidget uncomfortably and wipe away unwelcome tears. Notably, all of the reactors featured in "TEARS!" react in English, and the majority of the reactors are white. One woman speaks English with a Russian accent, and the non-white reactors all display the fluency of native English speakers. The reaction video thus offers the spectacle of cultural outsiders being moved by hallyu's emotional clarity, despite barriers of language, geography, and custom.

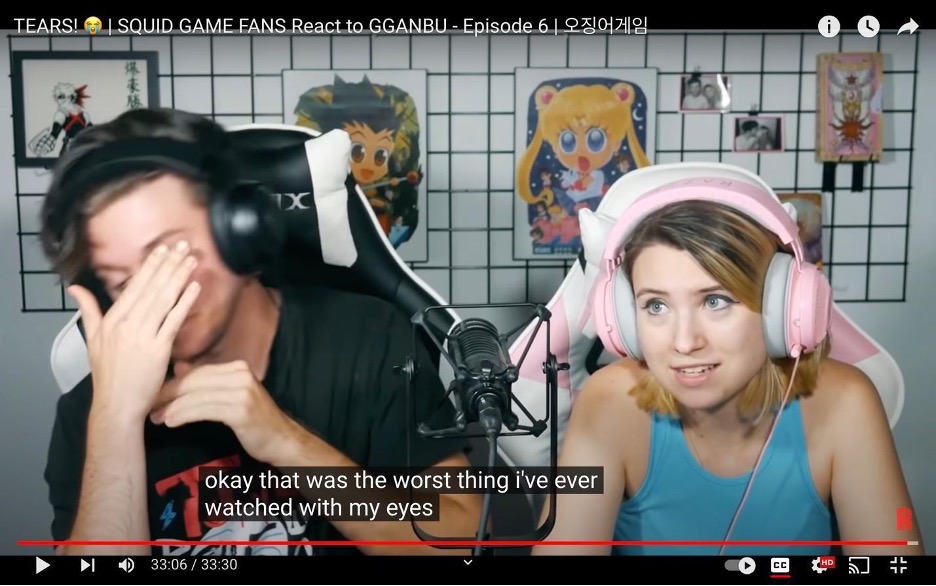

In the specific context of anti-Asian racism in North America, which exposed the triggering effect that the mere presence of Asian bodies in public seemed to have, it was notable and meaningful for me to see counterevidence in the filmed reactions compiled by Remixed by Raven. Ironically, the reactors' distress — the pain expressed at the game's/show's betrayal of the characters' relationships — makes the most convincing case for these Korean (i.e., foreign) characters' habitability as audience proxies. Rather than demanding "odorless," that is, deracinated American media, these viewers are unbothered or even compelled by cultural difference; indeed, they are moved beyond the norms of conventional melodramatic narrative, given the literal life and death scenarios staged by the show.13 The reaction video genre relies on emotional transference and vicarious experience, and the marble game episode heightens this transference to an almost unbearable degree. By the end of the reaction video edit, the show has come to seem sadistic. As the reactors reach the end of "Gganbu," they regain composure by narrativizing their feelings: "that was terrible"; "well, that was freaking depressing"; "ok, that was the worst thing I've ever watched with my eyes." "TEARS!" emphasizes the depth of the reactors' sympathies with the show's characters, while also highlighting the intensity of Squid Game's ability to create collective streams of co-feeling. While this ability to elicit emotion is often deemed manipulative, maudlin, or vulgar, the reactors seem to find in it a basis for further intimacy with other fans who have watched the show and suffered similarly (Figs 1 and 2).

"TEARS!" displays a uniformity of responses to the "Gganbu" episodes. Across the compilation, the same narrative beats elicit similar reactions — the reactors' tears flow in response to the same things. While a view of these reactions as representative of diverse audiences would read this consistency as a sign of "universal" humanity, when read as a culturally specific form of reaction — mostly North American Anglophone viewers who are specifically being targeted by Korean media producers as a generic "global" audience — the reaction compilation instead signifies a specifically conditioned cultural response: that of cult media fans who revel in the novelty represented by hallyu, even when this involves emotional discomfort. In this way, hallyu signals the privileging of a western audience or point of view as the still-prevalent constraint of "the global," while also making visible in embodied fashion what the new, global media landscape makes possible as affective bases for affinity, lateral connection, and even solidarity.

If hallyu calls attention to the challenges of defining global media, its odorousness or emphasis on national brand challenges the dominance of hegemonic, American-dominated media, which has historically promoted global whiteness as well as bourgeois heteronormativity. Works like Squid Game make it possible to see what happens when the global-popular makes itself visible in platformized meta-media like the reaction videos. As an event — activating the kind of mass public viewing that used to characterize television itself as a medium, ideology, and apparatus — Squid Game foregrounds pluralism through differential reception, against global television's earlier, homogenizing aspirations. I've written previously of hallyu as a Rorschach test — some see in it the advances of Asian techno-modernity, while others nostalgically fixate on traces of a traditional past.14 Again, these are characteristics that reside in the receiver, rather than inhering in the content or some singular Korean cultural essence. Questions of how media representation as public culture binds and transforms flows of collective feeling get reconstituted by hallyu as global media. In the case of Squid Game, flows of co-feeling made visible by the show's mediated spectatorship, whether in reaction videos or the discourse produced by the show's popularity, signify a plurality of meanings, despite repeated avowals of hallyu's universal appeal, which only serve to highlight the complexities that evade capture by this generic response.

Squid Game's mixed South Korean reception reflected a crippling double consciousness for locals ever preoccupied with the way that hallyu subjects them to scrutiny by outsiders. Sae-Byok and Ji-Young are portraits of femininity that refute the buoyant girlhood that appears in the images of youth that are produced and distributed by the transnationally popular K-pop industry, but this very opposition reveals hallyu's representational limits. Hallyu matters to the domestic audience because such representation has stakes to South Koreans — they are affected by the ways in which they are depicted in fiction — and many Koreans felt misrepresented by Squid Game. Especially given the opportunity to define Korean society in unprecedented ways to far-flung viewers, some South Korean viewers were disappointed by the show's limited scope of resistance. The triumph and redemption of an affable loser is nothing new — indeed, in the context of South Korean commercial media, Lee Jung Jae's very star text is founded upon such a role: Squid Game's Gi-Hun reprised Lee's breakout turn as the charming but incorrigible gambling addict Hong-ki in City of the Rising Sun (T'aeyangŭn ŏpta, Dir. Kim Sung-su, 1998). The impacts of Korean cultural producers looking to non-Korean platforms to produce content that stretches existing conventions of genre, industry practice, and domestic political discourse remain to be seen, but they undoubtedly affect all nodes of exchange. Thus, to answer who hallyu is for, it is for audience collectives that defy ethno-cultural labels, but that cohere around the affective intensities produced by hallyu's multiple scenarios of mutual projection and response.

Michelle Cho (@mhc727) is an assistant professor of Korean media at the University of Toronto.Her published work analyzes contemporary South Korean genre cinemas, self-reflexivity in hallyu television, the history of the Korean Wave, and K-pop's multi-sited fandoms. In the fall of 2022, she hosted a public conversation between hallyu stars and BFFs Lee Jung Jae and Jung Woo Sung at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF).

References

- Do Own (Donna) Kim, "The Joy Kill Club: On Squid Game (2021), a Roundtable-Monologue by a Korean Female Aca-fan," Henry Jenkins's Pop Junctions Blog, http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2021/10/30/squid-game-part-one/. [⤒]

- We Keun-woo,"중년 남성에 대한 연민에서만 일관적인, 마구잡이 서바이벌 '오징어게임' [위근우의 리플레이]" ["Survival at Random, 'Squid Game' only consistently compassionate towards middle-aged men [We Keun-woo's Replay]"] The Kyunghang Sinmun, September 24, 2021. https://n.news.naver.com/mnews/article/032/0003099713?sid=102. [⤒]

- Lee Jung-Hyun, '기생충'처럼 계급사회 꼬집은 '오징어 게임' 글로벌 히트' [Like 'Parasite', 'Squid Game', which pokes at class-divided society, is a global hit], September 23, 2021. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20210923067852005.[⤒]

- Examples of sageuk include the now classic 2000s series Dae Jang Geum (Jewel in the Palace) and Seondeok Yeowang (Great Queen Seondeok).[⤒]

- Jason Jeong, "Korean Television is in the Midst of a Radical Renaissance," Jacobin, March 18, 2022. https://jacobin.com/2022/03/radical-renaissance-contemporary-korean-television-violence-neoliberalism.[⤒]

- https://www.pastemagazine.com/tv/k-drama-popularity-explained-romance-tv-shows/.[⤒]

- Soo Youn, "How Cho Gue-Sung became the breakout thirst trap of the world cup," NBC, December 7, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/cho-gue-sung-became-breakout-thirst-trap-world-cup-rcna60525.[⤒]

- Jungbong Choi, "Hallyu vs. Hallyu-hwa: Cultural Phenomenon vs. Institutional Campaign" in Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the Age of Social Media, eds. Sangjoon Lee and Abe Markus Nornes (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 31-52.[⤒]

- Bhaskar Sarkar and Bishnupriya Ghosh, "The Global-Popular: A Frame for Contemporary Cinemas," Cultural Critique 114 (Winter 2022): 3.[⤒]

- IRamon Lobato's Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution (NY: New York University Press, 2019). [⤒]

- Remixed by Raven, https://youtu.be/ZeKIB5__XOE.[⤒]

- Chi-Yun Shin, "Art of Branding: Tartan 'Asia Extreme' Films," Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 50 (Spring 2008). https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc50.2008/TartanDist/.[⤒]

- Iwabuchi Koichi, "Marketing 'Japan': Japanese cultural presence under a global gaze," Japanese Studies 18, no. 2 (1998), 165-180.[⤒]

- Michelle Cho, "Pop Cosmopolitics and Kpop Video Cultures," in Asian Video Cultures, edited by Joshua Neves and Bhaskar Sarkar (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017): 240-265.[⤒]