Minimalisms Now: Race, Affect, Aesthetics

In Something Close to Music, a recent posthumous collection of his scattered art criticism (plus poems and playlists), John Ashbery writes of the work of the late Icelandic painter Louisa Matthíasdóttir (1917-2000). Her colorful, stark landscapes — depicting horses, houses, mountains, fjords, water, sheep, and the occasional person or dog — powerfully project the extreme sublimity of her native island nation, where the sublime at the level of landscape derives from a mix of the maximal and the minimal. Matthíasdóttir's painting, when considered alongside Ashbery's descriptions of it and filtered through his poetry, suggests that an effective minimalist aesthetic not only depends upon the maximal as something to define itself against, but is paradoxically partly maximal itself, insofar as the more successful it is in its minimization, the more maximal is its impact.

The minimal / maximal paradox exemplified in Matthíasdóttir's work is touched on by an artist of more recent vintage, Roni Horn. In her "Iceland Writings" in Island Zombie, she evokes Wallace Stevens in describing the Icelandic Highlands as "the nothing that is." Horn sees the landscape there in terms that are paradoxically maximal and minimal at once when she writes of Iceland's "full-up vacancy," of its "nothing of open space" and its "possibility of infinity." The "not nothing of the desert," the "feeling of the absence of secrets," and the "absence of the hidden" in Icelandic vistas intrigues her. She especially notices the lack of trees, a pregnant dearth. Their "absence brings out the [landscape's] remarkable nature" for, amidst the vistas, the "views [themselves] are the trees of Iceland." The treeless view is like a tree in its "way of relating things: the earth to the sky, the light to the dark, the wind among its leaves to the stillness that surrounds it, the small spaces within the tree to the vast spaces it inhabits."1 This is another way of saying that the minimal can stimulate maximal attentiveness in a way the maximal itself alone can never do.

The landscape of a world without trees yields, in the twenty-first century, a new pastoral mode for the Anthropocene. The classical pastoral was always shot through with the elegiac anyway, so the genre prepares us well to make use of the self-made dying world. Yet maybe in our romanticized but real destroyed Arcadia, we are missing the bigger picture; maybe we can't quite see the forest for the loss of trees. "[T]here were many who flocked to the island," writes the University of Iceland's Dr. Birna Bjarnadóttir in a lyrical fragment, who "allowed themselves the luxury to observe the people as being different. Thereby, one could observe the observers projecting their transparent need for a different kind of place here on earth. But why should Iceland be different from the rest of the neo-liberalized world?"2 As if seeing Iceland's vistas through brand-covered and smog-smeared glasses worn from home, the outsider or newcomer neglects to notice that the country is just another example of what Bjarnadóttir calls "the Republic of the Kiosk."

For her own part, Louisa Matthíasdóttir left Iceland as a young painter in 1942 and headed to New York City, where she lived for the rest of her life. She returned home frequently, though, both literally and in her landscapes. Curiously enough, she saw her native vistas in a manner similar to the alien Horn. Speaking to Mark Strand in 1983, Matthíasdóttir remarked, "I try to go back to Iceland at least once a year. [. . .] One of the characteristics of Iceland that I like is the fact that there are no trees to speak of. When there are trees one doesn't really see beyond them, one can't get a sense of the horizon. In Iceland, the landscape is unobstructed, allowing one to see for great distances."3 The greatest distance one can see in New York City is up, so it must have been quite the change of perspective.

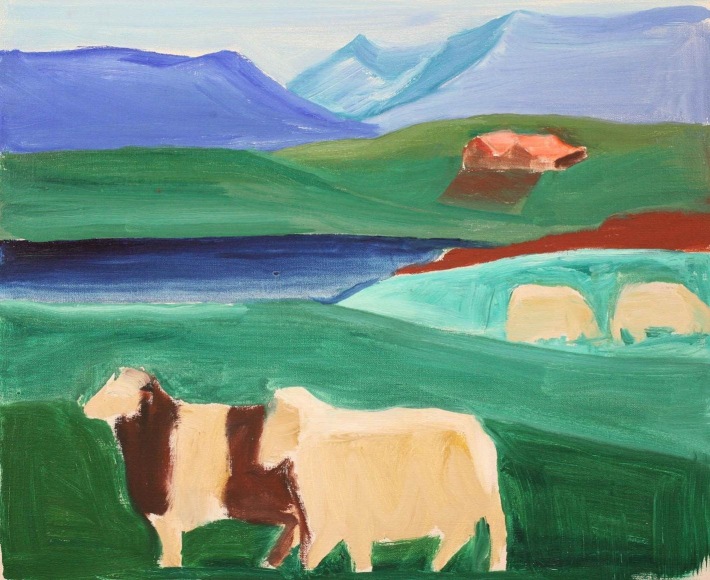

The oeuvre of Ashbery, one of Matthíasdóttir's most perceptive admirers, starts out not treeless, of course, but instead begins with Some Trees (1956). The title poem of that volume remains among the loveliest little American lyrics "of relating things," to return to Roni Horn's phrase. No surprise, then, that in seeing Matthíasdóttir's landscapes, Ashbery notes the arboreal absence: "Apparently there are no trees or sfumato in Iceland." The former aporia is a natural fact — if not totally so, then mostly — while the latter absence ("sfumato") refers to the technique of shading colors together, of softening the transition of tones so that an out-of-focus, hazy quality is achieved. Matthíasdóttir paints without this technique in distinctive colored blocks and triangulated curves. "The buildings are simple gabled shapes," observes Ashbery, "white with colored roofs, and few if any windows, like the houses in Monopoly." Her "animals are almost emblematic," including the "Icelandic sheep, a rectilinear beast" which "seems to have been designed by nature as an illustration on a building block," whose "two-dimensional squarishness" is emphasized "with only a slight trace of humor."4 (The same can be said for her depictions of the hestar, the sturdy Icelandic horse, her many paintings of which were the subject of a 2022 show at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery.)

"[W]ith only a slight trace of humor"—and yet, there it is—a trace, if only slight.

This is how Ashbery writes of Matthíasdóttir, namely, that in relation to some particular abstract quality or thing (such as humor or mystery, secret or dream), Matthíasdóttir assumes through that abstraction an aspect of entirety, which is acknowledged as a maximal "whole" without obliterating the right of the minimal particular to exist. "There is an increment of something else," he writes, "a trace-element of mystery, a dreamlike tinge, which allows the picture to deploy its loose big shapes and go about its business, just by keeping the whole alive. [ . . . ] So, though there are no unnecessary secrets, there are enough—the ones the average person, as opposed to the Machiavellian intriguer, would have." This "something else," this extra quality "gives Matthiasdottir's painting, despite its tendency toward broad simplification, an air of heightened realism — a kind of trompe l'oeil that works on a mental rather than an optical level."5

The minimal appears here as a matter of mental scale. Radically yet modestly relative, it is saturated with contingency, as it depends upon the maximal to maximize its impact. It is set against and at odds with the maximal, and yet it is also beholden. As a negative index of a world shot through with ever more, the minimal seems ever more impossible and thus increasingly powerful in its potential as a counterbalance to our culture. It repudiates an overwhelming and imperial excess. It reduces information to clear a space for thought, to allow us not to feel (excess makes us feel too much, as a prelude to feeling nothing at all) but rather to attend to what we are feeling. Minimalism is quiet so we can finally hear ourselves.

In Matthíasdóttir's so-called "small paintings," one especially encounters this rich reduction, this visual quietude. Even their names and dimensions have a reductively grounding, quietly calming effect: "Green House, Red Roof" — 8 x 12 inches; "Sheep and Yellow House" — 13 x 16 inches; "Sheep: Two White, One Black" — 8 x 10 inches; "Ewe with Lambs" — 14x17 inches; "Red Roof, Yellow House" — 10 x 11 inches; "Two Sheep, Yellow Sky" — 9 x 13 inches. The simplicity of these titles evoke a lost morality of thrift and a rejection of dissimulation. Formal and humane, the pictures are layered without tricks of perspective. What lies outside the frame — there are more sheep than this, more houses than this (if only barely), more mountains and water and land than this — only matters at the moment for being excluded.

These paintings, although small, are not dainty or miniscule or cute. (The truly minimal is none of these things, though it is often mistaken to be. Of course this is often gendered.) Nor are they deliberately unfinished or a just-getting-started. As one critic notes in Louisa Matthiasdottir: Small Paintings, she "painted most of them, in fact, after she had completed related large paintings — almost like plot synopses. Unlike many artists' small works, they are not preliminary sketches or studies."6 Instead, they are after-the-fact reductions that attempt to make the minimal "most" from a relatively maximal predecessor, a "situation" of sorts that the artist created herself and "rectifies" through reduction. This is similar to the way in which much is made of the minimalist beauty of the Icelandic landscape by members of the very same species responsible for wrecking maximalist destruction upon it in the first place.

When discussing the artists he values, Ashbery often also describes himself. Matthíasdóttir and he share a modest reticence (he remarks on her lack of "superfluous secrets," but as with him there are just "enough"); they both retained human-sized mystery through long productive lives in a demystifying age. "The land is clean, chilly, and open," he writes of her landscapes. "Sometimes two figures stand in the foreground, not too close together and casting the long shadows one associates with de Chirico. This might seem to invoke a secret or a mystery, but if so it does it only long enough to make the point that this bit of poetry is only a minor ingredient — essential, perhaps, but small—in a game where formal concerns override others without suppressing them."7 Poetry . . . but just a bit; an ingredient . . . but only minor; perhaps essential . . . but a small essentiality. Every claim of any volume here is countered by a deflective diminuendo. One is reminded of his description of Parmigianino's looming hand in "Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror" (which was also his own self-portrait): "as though to protect / What it advertises."8

Despite being a maximal poet—indeed, an era-defining maximalist—Ashbery is also a minimalist. His maximalism can be found in the incredible variety of his diction and in his deployment of so many genres, forms, and tones. This indicates a maximally open aesthetic in which nothing is prima facie excluded. Everything is everything, as the circular saying has it, and everything is grist for the lyrical mill. Harold Bloom's prescient claim (which only became truer with time) that Ashbery "implore[d] the world daily to arrange itself into a poem" is relevant here.9 If the world is a poem for Ashbery, an Ashbery poem is also a world. Such was the point made by Angus Fletcher in A New Theory for American Poetry, which sees Ashbery as a maker of the "environment poem"—not a poem about the environment, but rather a poem that is itself an environment. When one also considers Ashbery's prolixity, productivity, and longevity, his status as a maximalist is exceedingly clear.

Yet Ashbery's vision of Matthíasdóttir shows us two aspects of his essential minimalism: first, in his protective advertisement of the artist on the margins, in the shadows; second, in his instinctive diminuendo in making claims for art. Both of these aspects represent a minimalism of (the perception of) aesthetic and social value, an ironic flip whereby the eccentric is central, smaller is bigger, and the margin is shown to map and even encompass the whole.

Examples of Ashbery's celebration of "outsider," marginal figures of minimal reputation are numerous, the most pronounced being the attention he paid to lesser-known writers in his Norton Lectures, published as Other Traditions (2001). A more recent case can be found in the late Joan Murray's The Complete Poetry (2017), work championed by Ashbery and rescued from oblivion. As Farnoosh Fathi, the collection's editor, wrote in her introduction: "This book almost dedicates itself—to the memory of John Ashbery, one of the most generous, constant proponents of writers of unclassifiable 'other traditions' [. . .] Ashbery raised the bar for all poets to pay closer attention to the young, forgotten, or unsung."10 And as he did with writers, so too he did with painters. This is not to say that Matthíasdóttir is "unknown" or is devoid of a significant international reputation. Yet in an extremely fine and comprehensive appreciation written just before her death, Jed Perl noted that she "has never become a big name in New York" and described her as an "artist's artist."11 Interesting then that a poet of the "New York School" was among her staunchest advocates; but of course, a person who once memorably described Elizabeth Bishop as a "poet's poet's poet" would be attentive to an "artist's artist," especially if she was never "big."

As for diminuendo and the making of muted claims, only a non-monumental maximalist such as Ashbery could voice his opinions so effectively, with quiet conviction through a subtly ironic minimalism. (Given the overwhelming nature of our aesthetic, attentional, and informational glut, any serious contemporary minimalism is by necessity ironic.) I still recall the relief I felt in first reading Ashbery's early long poem "The Skaters," when after an overwhelming build-up of extended metaphors for poetry itself and a cacophony of clangorous instruments representing the very sound of lyric, he said simply: "Mild effects are the result." On the one hand the phrase frees us to experience flights of transcendence, to engage with the tradition, to safely inhabit one's own cluttered mental attic, one's barely curated psychic collection of arbitrary stuff. On the other hand the phrase frees us to finally let go of those things — and nothing big has to happen. Not every encounter with poetry or painting has to be monumental. Despite whatthe archaic torso of Apollo said to Rilke, art, according to Ashbery, doesn't always mean having to change your life.

He tells you this over and over, and yes, he tells it to you. As Helen Vendler said with her customary sensitivity: "Since the loop of co-creation between Ashbery and his reader is indispensable if the reader is to follow and understand his poetry, Ashbery [ . . . ] conceives of lyric as a projected colloquy. There can of course be no actual colloquy — the poet may very well be dead by the time a future reader comes across the poem — but it is the imagined projection of colloquy with an invisible listener that enables the Ashbery poem to be written at all."12 Ashbery has this conversation with us throughout his work, preparing the posthumous way. He gave us "Sortes Virgilianae," for instance, with a title referring to the practice of bibliomancy whereby random bits of Virgil revealed the future or gave advice for the present. The poem prompts the question: How should the posthumous poet be remembered today? And it answers: In scraps at most, or maybe not at all. For as Ashbery puts it: "Things pass quickly out of sight and the best is to be forgotten quickly / For it is wretchedness that endures."13

The death of the poet changes the scale of the work. The matter of what and how to remember comes upon the reader with full force after having been repressed for so long in anticipation. Ashbery's longevity made this matter more interesting ahead of the fact of his death. And perhaps it is indeed, as he prophetically suggests, better to be quietly (or at least "quickly") forgotten. He laid the groundwork for his readers to accept the possibility — even the desirability — of minimal afterlives.

There's a perception that Ashbery is an anti-closural poet, since the individual poems feel so "open." This also always seemed to apply to his oeuvre as a whole, which in a sense will always be open and vast. In another sense, though, it is now sealed by mortality. Barbara Herrnstein Smith once wrote that "when a conclusion [to a poem] is not structurally predetermined, closure must be secured — if at all — through some other means." In such cases, "a sense of finality and stability is secured or strengthened by certain terminal features or special devices that tend to have closural force more or less independent of the poem's particular formal or thematic structure."14 Death is just such a device. In another posthumous Ashbery book, the last page of the last poem asserts that "the point is to find an extra-sensual way to be without it."15 In this way, death is a deduction or minimization that can be partly recuperated through the addition of having to find new ways to know the work of the deceased and the art that is left in its wake.

Ashbery closes his loving, incisive look at Matthíasdóttir by writing that "one returns to these pictures, as year after year they paradoxically both expand and simplify the world they have chosen to explore, for their strange flavor, both mellow and astringent, which no other painter gives us."16 Substitute "poems" for "pictures" and "poet" for "painter" and you have a self-description. A worthy goal it surely is, to "paradoxically both expand and simplify," to achieve the expansion of simplification. But it is a goal commensurate with the way in which the minimal and the maximal are always intertwined. Four pages on from Ashbery's assessment of Matthíasdóttir in Something Close To Music is a poem titled "Like Air, Almost," that begins:

It comes down to

so little

And yet so little is often so much. But if the minimal isn't your thing, he has you covered too, for the final line of the poem once again frees you, a gentle consolation from a generous poet:

Hey it's all right.17

But from all right to what? At the start of one of his longest poems, "The New Spirit," Ashbery begins: "I thought if I could put it all down, that would be one way. And next the thought came to me that to leave all out would be another, and truer, way." Yet "the truth has passed on," "to divide all."18 Most crucial of words for Ashbery — all — that word both so large and so small, that word that "small" contains. It perfectly epitomizes the maximal / minimal paradox in the tiny space of three letters.

"Hardly anything grows here," wrote Ashbery of a mysterious minimal landscape in his sonnet "At North Farm," "yet the granaries are bursting with meal, / The sacks of meal piled to the rafters." The interplay of the fecund and the barren found therein (with its origins in the Finnish Kalevala's inexplicably productive "Sampo," a sort of magic perpetual mill) speaks to how matters of minimalism and maximalism are not just aesthetic but are literally existential. What can and can't we live with? What can and can't we live without? How much is too much and what is not enough? Perhaps Ashbery's appreciation for Matthíasdóttir's mysterious minimal landscapes is accounted for by his seeing in them a version of his own aesthetic and existential attempt to square the perpetual circling of the fecund and the bare.

It is probably worth pointing out that Matthíasdóttir didn't only paint landscapes, landscapes of her native land scraped of its trees a millennium ago and left in desolate beauty. Her streetscapes of Reykjavik — thoroughfares with a few parked cars, a pedestrian or two, bordered by fairly well-appointed homes — represent colorful streets that a century before she painted them were nothing but houseless cart-paths of frozen mud in some bleak colonial outpost. And her still-lives are just as spare as the landscapes — an eggplant, a melon, a dish, a cup, inert on a table with patternless cloth — yet made of items gleaned from the markets of Manhattan's teeming fullness. In the former case she shows the more that came from less, in the latter case the small that comes from the large.

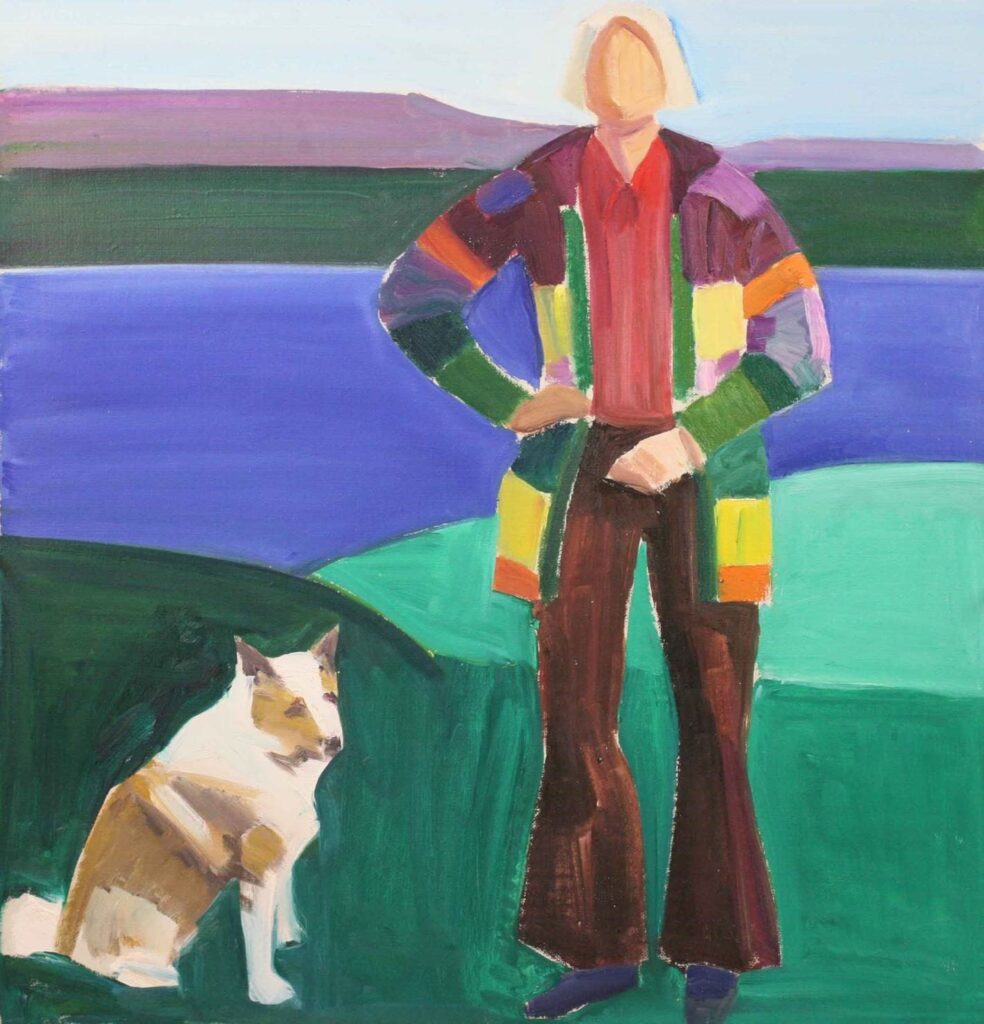

Then there are her portraits and self-portraits, especially the ones in which a body fills the entire frame. The viewer sees that the hang and the bend of the limbs has been quickly but surely articulated and that it all "fits its hollow perfectly," as Ashbery said of the soul in his poem of Parmigianino. And yet the faces in those colorful, warm, witty, assured, unnerving paintings are, like her landscapes, denuded. In the most striking of them, say Self-Portrait with Coffee Cup or Standing Self-Portrait with Dog or Self-Portrait in Long Striped Sweater, the faces are devoid of features, the faces are almost totally blank. Somewhere in Iceland someone is methodically planting trees.

Andrew DuBois is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Toronto. He is the author of Ashbery's Forms of Attention and three other books, the most recent of which is a collection of poems titled All the People Are Pregnant. He also co-edited The Anthology of Rap and Close Reading: The Reader.

References

- Roni Horn, Island Zombie (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 184, 3-6, 181.[⤒]

- Birna Bjarnadóttir, a book of fragments (Manitoba: KIND Publishing, 2010), 27.[⤒]

- From Mark Strand, Art of the Real (1983), quoted in Jed Perl, "Clarity: The Art of Louisa Matthiasdottir," in Louisa Matthiasdottir, Edited by Jed Perl (Reykjavík: Nesútgáfan Publishing, 1999), 133.[⤒]

- John Ashbery, Something Close to Music (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2022), 121-122.[⤒]

- Ashbery, SCTM, 123.[⤒]

- Nicholas Fox Weber, in Louisa Matthiasdottir: Small Paintings (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1986), 51.[⤒]

- Ashbery, SCTM, 122.[⤒]

- John Ashbery, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (New York: Penguin, 1975), 68.[⤒]

- Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence (London: Oxford University Press, 1973), 145.[⤒]

- Farnoosh Fathi, in Joan Murray, The Complete Poems (New York: NYRB, 2017), xxxiii.[⤒]

- Perl, "Clarity," 125. [⤒]

- Helen Vendler, Invisible Listeners (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 60.[⤒]

- John Ashbery, The Double Dream of Spring (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1970), 74.[⤒]

- Barbara Herrnstein Smith, Poetic Closure (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968), 151.[⤒]

- John Ashbery, Parallel Movement of the Hands (New York: Ecco, 2021), 177.[⤒]

- Ashbery, SCTM, 123.[⤒]

- Ashbery, SCTM, 127-8.[⤒]

- John Ashbery, Three Poems (New York: Viking, 1972), 3.[⤒]