Minimalisms Now: Race, Affect, Aesthetics

Hinge Wants You to Find Love

Hinge, its tagline wants you to know, is the dating app "designed to be deleted." This wasn't always the case: launched in 2012, the app entered a new phase of development after an article in Vanity Fair accused it — along with competitors Tinder and OkCupid — of facilitating a full-blown "dating apocalypse."1 The piece argued that the technology of modern romance had, in its thoroughgoing gamification, become a hindrance rather than aid to connection: swiping had so instrumentalized dating that the process was now a mere numbers game.2 While Tinder quickly leapt to its own defense,3 Hinge seemed to take the indictment to heart. It subsequently removed the swipe option and began to rebrand itself as the face of sincerity and authenticity restored to online dating.

Hinge's capacity to transform dating in the digital age is, to be sure, overstated. But there is something stranger than mere self-promotion in Hinge's well-timed crisis of conscience. This "something" has less to do with curing the ills of modern disconnection and more to do with the stories we tell ourselves about the kinds of mediation we want. Corporate doublespeak cannot, I think, entirely account for why Hinge couches its style of mediation so insistently in the language of self-erasure:

In today's digital world, singles are so busy matching that they're not actually connecting, in person, where it counts. Hinge is on a mission tochange that. So we built an app that's designed to be deleted.4

That an extra-digital mode of connectivity — in-person, "where it counts" — should be midwifed by the very technologies that endangered this connectivity in the first place would seem to present a contradiction in terms. More intriguing, however, is the way in which this contradiction is taken up in Hinge's tongue-in-cheek embrace of self-destruction. Ads feature an anthropomorphized creature named "Hingie" set on fire, run over by a car, fed through a deli slicer while a voiceover reassures viewers that Hinge "wants you to find love" and to "destroy us while you're at it."5 The glee with which the ad incinerates, dismembers, and pulverizes the thing it promotes — and implicates users in this destruction — indexes a deeper ambivalence about the app's status as mediating product. "You don't hear a lot of businesses refer to their own demise, much less celebrate it," the company manual muses.6 This — not the technology's claim to revitalize human relation, but the style of self-effacement that becomes its aesthetic signature — is where Hinge's intervention lies.

There is, to be sure, a story here about disavowal's lasting marketability — about how claims to not be selling you something enable that thing to be sold to you, albeit in slightly different packaging. Such a canny reading would likely have less patience with Hinge's slogans. But what gets overlooked in an easy dismissal of the sound bites above is what forms this particular kind of ambivalence about commodified mediation takes. What happens when we tarry with the fantasies and anxieties articulated through the commodities themselves, dubious though their promises may be?

Undermediation: a style of mediation whose primary feature is the undercutting of the very form the conveyance is couched in. 7 I say under- rather than anti-mediation because Hinge's case for its own existence rests precisely on a distinction between reworking something and getting rid of it altogether. The objective is not a total overhaul, but a recalibration of existing forms. If other reimaginings of social media, real or fantastical,seek to trouble the relation between mediated and unmediated by more explicitly troubling the form or context of the encounter, 8 Hinge does not suggest that we, lonely denizens of a digitally-saturated world, should shun dating apps altogether, but that we, in our desire to find one another, need less intrusive versions of these apps. Beneath the over-the-top, slapstick-gruesome deaths of Hingie, there is a quieter claim to mere-ness, to being around for "just" as long as one is needed. While Hinge's mantra is transparently self-interested — choose us, we're less bad — I also wonder whether we might read in "designed to be deleted" evidence of common hopes and frustrations that attach to new-old technologies promising to bring us together.

The wish for undermediation speaks to a persistent concern about reliance on technological go-betweens, even as it holds out for what those forms of mediation, properly recalibrated, might make possible. What emerges is a telling anxiety about how to determine — even how to measure — whether the technology has its heart in the right place. Sometimes, existing metrics need to be discarded. Hinge founder Justin McLeod describes how the company's pivot necessitated a shift in ways of understanding their user's needs: traditional social media indicators of successful engagement, such as many minutes spent "in-app" or high retention of users, became indicators of an over-reliance on the technology and a need to reevaluate existing metrics.9

In short, when it comes to its own status as mediation, Hinge has misgivings. Its fascination with self-destruction reveals a wish — for mediation that is less overbearing, all-consuming — that, as we will see, extends beyond the world of dating apps. I want now to juxtapose Hinge and its promise of being "designed to be deleted" with two other cultural objects: the 2015 video game Undertale and the 2003 film Lost in Translation. My account of undermediation is, admittedly, eclectic, tracing its logics at work in a dating app advertisement, indie RPG, and romantic comedy-drama. This list is not meant to be exhaustive. Instead, I'm interested in what begins to coalesce around these instances, which are plucked from a much larger pool: a recurring set of aesthetic motifs that speak to a commitment to thinking about mediatory technologies as affective ones, too.

You Don't Have to Destroy Anyone

Undermediation as an analytic makes it possible to talk about appeals to aesthetic innocence as part of a concerted, culturally prevalent style. Claims about mediation made in the negative voice are, more often than not, cancelling something out in the interest of transforming or protecting something else. Take the avant-garde filmmaking movement Dogme 95 and its "vow of chastity," which frames its aesthetic intervention primarily as a set of not-to-dos: "sound must never be produced apart from the images," "props and sets must not be brought in," "the director must not be credited," and so on. Largely technical and at times micro-manage-y, the list of abstinences nonetheless delineates a vision of "traditional" filmmaking and storytelling that exceeds the minutiae of any particular shot. Restraint may be the aesthetic program, but the real objective lies elsewhere — in the case of Dogme 95, the "rescue" of film from bourgeois "decadence" and the forcing of "truth" from characters and settings.10

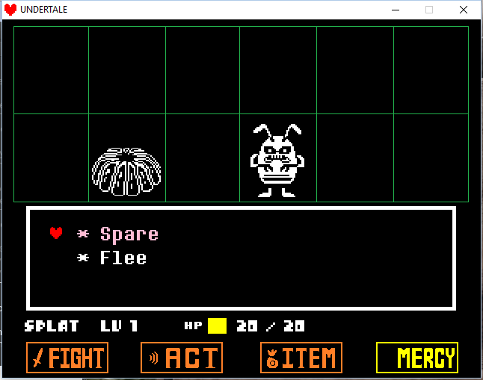

The 2015 video game Undertale, acclaimed for its heartfelt take on RPGs' usual "killed or be killed" ethos, likewise frames its intervention in the negative: it is "the game where you don't have to destroy anyone." The game adds alternative interactions with nonplayer characters (NPCs): in contrast to role-playing games that require defeating adversaries in order to gain access to new levels, Undertale gave players the choice to "spare" characters rather than fight them. The choice to avoid battling NPCs is literalized in the mechanics of dodging — in order to unlock the "spare" option, one must navigate several bullet hell rounds. In many ways, the choice to bypass fighting requires a nimbler and more involved interaction with game mechanics than electing to battle — for one, the pacifist must often interact with characters multiple times in order to figure out what combinations of actions to use in order to successfully "spare" a character. (I also ended up doing more research as I was playing to determine whether I was on my way to the "good" ending or whether I had inadvertently fought a monster.)

"Undermediation" feels like a misnomer here: if anything, not having to kill or fight characters introduces more, not fewer, layers of mediatory complication. Players can end up with a "Neutral," "True Pacifist," "Genocide," or "Hard Mode" ending; different dialogue and different actions appear depending on which round you're on and which choices you've made previously. And yet, Undertale'scultural intervention has been couched in terms of abstention — abstention from technologies of relation that desensitize their players to violence, absolve them of responsibility for the actions they take in the game, or that impose distance between user and creator. This ethos bears out in Undertale's deliberately rudimentary aesthetic —while the game was not, in 2015, running on systems with archaic 8-bit processors,11 its interface uses nostalgic pixelated graphics and a "glitchy" soundtrack reminiscent of the 8-bit style of early Nintendo. The lo-fi aesthetic lends the game of a do-it-yourself feel — its description on Steam underscores that Undertale was "created mostly by one person."

Games that are not 8-bit but "8-bit inspired" disclose the ways in which the form of technological objects mediate affective attachments as well. Philosophers of new media discuss this in terms of a desire for the "analog": technically a term for a type of signal that involves gradations in continuously variable quantities (as opposed to the digital, which represents data as a sequence of discrete values), analog as a structure of feeling has more to do with a sense of what is lost in the turn to code.12 Analog in this usage points to what Laura Marks calls a nostalgia for "perceptual innocence," a desire for the "dumb wonderment" that physical reality alone is (ostensibly) capable of inducing.13 Such longing for the every-receding horizon of unmediatedness lodges itself in counterintuitive forms: digital videos treated to simulate kinds of decay and interference that really only affect analog videos,14 online communities that virtually mimic tactile practices of bookbinding and textile production,15 among other things.

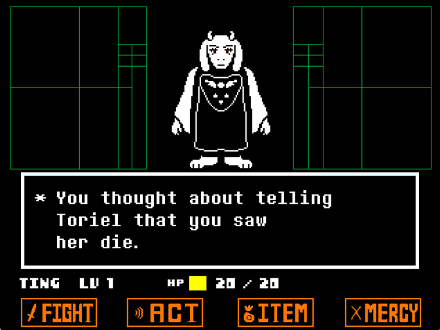

For Brian Massumi, on the other hand, the analog surfaces not through particular kinds of objects, but through the user's interaction with digital forms.16 Translating zeroes and ones back into figures of thought and feeling — reading the words that appear on the screen, navigating one's online avatar — reintroduces messy embodiedness and ungovernable variability into the process. Experiencing Undertale foregrounds choices made in the game as choices, ones that are not left behind in the transition from one level to the next, but stick. Early on, players must decide whether to battle the maternal figure Toriel, who has guided the game's protagonist through a tutorial, brought them into her home, and fed them pie. Once one decides to kill Toriel, the choice is irreversible: should a player regret their decision and return to the start of the game in an attempt to choose differently, they will realize that their game history has not been erased.

To repurpose Hinge's somewhat self-congratulatory observation, it's not often that a game guilt-trips its own user. Guilt becomes the mark of a situation made, in retrospect, slightly more "real." While Undertale does not escape its digital form (as McKenzie Wark points out, all gamespaces only accommodate the digital, ultimately translating continuous movement into either/or decisions),17 the game seeks to precipitate experiences beyond the bounds of the game. Such porousness between inside and outside aligns with the way Creator Toby Fox talks about his own frustrations with RPG "tropes," which tend to take for granted things like the disposability of NPCs, and how Undertale frustrates those conventions.18

Undermediation is less about the simple fact of simplification or reduction than the desire for the relations facilitated by mediatory technology — between users in a dating app, between a player and NPCs, for instance — to look different. The most striking thing about undermediation is that it tries to be both an aesthetic program and a theory of relation. So: what kinds of social desire are being encoded here, exactly? What are the proposed terms of undermediation's repaired or rejuvenated sociality?

No Need for Translation

While Undertale stages these questions in elegant ways, there are affective histories at play here that go back longer than the digital/analog divide. Loneliness, in particular, comes up often in the rhetoric of undermediation. Typically couched as a structure of feeling that arises with the failure of the social, loneliness is in fact anything but. After all, theories of alienation tend to leave unspoken all kinds of assumptions about the social as an aspirational space of intersubjectivity and belonging.19 Less about abandoning or being abandoned by the social than about wanting it to be different, loneliness bears an indeterminate relation to the actual presence of other people: one might very well feel lonely in the midst of an interaction, or feel less lonely when on one's own. Whether one feels isolated or not is based on the felt absence of a desired or valued relation rather than any objective measure of solitude.20

For an aesthetic example of this, we might turn to Lost in Translation, that cinematic ode to American loneliness set, tellingly, against the familiarly exoticized backdrop of hypermediated Tokyo. Flows of multinational capital have conspired to bring washed-up actor, Bob Harris, to promote Japanese whiskey to a populace who recognizes him and his star power, but whom he cannot communicate with. The question of mediation arises in no small part from the film's central theme of linguistic alienation. For instance: while filming an ad for the whiskey, Bob's translator repeatedly fails to commensurately translate the director's detailed instructions, compressing entire monologues into laconic phrases like "turn to camera" and "more intensity." The withholding of English-language subtitles means that viewers who do not already understand Japanese are just as in the dark as Bob is.

Unable to understand the direction he is given, and assuming he cannot be understood in turn, Bob puts on a one-man show for no one in particular, papering over awkward pauses and miscomprehension with bratty ripostes and digs ("'more mysterious,' yeah. I'll just try to think, 'Where the hell's the whiskey?") that he does not expect a response to. Surrounded by people whose hospitality only further confirms their inability to anticipate his needs, Bob is eager to leave Tokyo. This is until he meets Charlotte, a recent college graduate who has followed her husband to Tokyo and is staying in the same hotel. The two bond over their shared insomnia and broader aimlessness. Each also comes from a context of disappointing relations — emblematized, it turns out, by mediatory technologies. We watch Bob fail to connect on the phone with his wife, who is (understandably) impatient with his shifting moods and general negligence; we see Charlotte try to communicate with her photographer husband, who is more interested in his work than in working through her post-college existential crisis. Bob's and Charlotte's futile exchanges with their spouses mirror the interactions that Bob has with the locals: each time, the media involved (photographs, television, telephones, language) creates confusion, miscommunication, and frustration. Sometimes the mediatory technology just plain breaks down: Bob has trouble hearing his agent on the phone because there is no reception in the studio.

In stark contrast to these scenes of disconnect, the film ends with a minimally mediated interaction between Bob and Charlotte: a wordless exchange between the two as Bob leaves for the airport. The exchange is wordless not because words are not used, but because the film famously withholds what Bob whispers into Charlotte's ear. If this moment in the film is often read as one of radical privacy (Bob's words are for Charlotte's ears only, not ours), I would like to propose in the spirit of this thought experiment that this moment can also be read as an undermediated one. Language, a going concern throughout, is shown in this scene to be ultimately unnecessary: whatever the two need or could say to each other in this moment has already been expressed at other moments, in other ways. If much of the film has been spent, for the viewer who does not speak Japanese, with untranslated dialogue that is deliberately left inaccessible, this is, in contrast, is a moment whose resonance is supposed to obviate translation or even transcription. The use of language here is deflationary rather than climactic insofar as it doesn't reveal any crucial information; it doesn't matter what Bob says to Charlotte — we already feel how they feel about each other.

This is undermediation's animating wish: mediatory material that gets out of the way when the time comes, that can be used and discarded at will. Mediation that does not exclude immediacy. The problem with the moment of undermediation in Lost in Translation is that it is built on the logic of loneliness, which is far from a neutral description of relation. In order to capture Bob and Charlotte's intimacy, Lost in Translation subordinates all other relations that appear in the film. Because the film is about two Americans finding one another abroad, these other, narratively subordinated relations mostly involve the exoticized others who are relegated to mere backdrop or caricature. Loneliness in proximity to other people, and the feeling of connecting with someone in particular, drives the film, which is fascinated with minor moments of insiderness: making eye contact in a crowded elevator, sharing private jokes in the presence of (seemingly) uncomprehending, racialized others. Bob and Charlotte are lonely for the first part of the film not because there isn't anyone, but because there isn't someone who gets them. Lost in Translation's fantasy of undermediation is one of finding the dyadic in the crowd; it imagines that this dyadic intimacy offers respite from a globalized world in which anonymity and intensified loneliness are, ostensibly, the default.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the disavowal of one's own medium contains an unspoken dream of transcending it. To return to our first object: Hinge claims that its design seeks to minimize the amount of time users spend interacting with the product. Rather than seeking to maximize "minutes in app" (an industry metric often treated as an indicator of an app's success) by increasing the range of interactions that take place within the app, Hinge seeks to set up interactions in "real life" in order to help users to bypass the app altogether. (Or what about Meta's tagline for its projected virtual reality universe: "the impact will be real"?) Again, it is the form of the claim rather than its accuracy that interests me — Hinge is clearly, contrary to its claims to self-erasure, still interested in expanding its user base and thus getting more people to be "in app." Far from an exercise in corporate modesty, this preoccupation with users' lives beyond the app indicates something of Hinge's and Facebook's overweening ambition, its drive to curate something more than an in-app experience. In light of this cluster's theme, "Minimalisms Now," we might say that these objects apply minimalism's aesthetic protocol to non-minimalist ends: undermediation's promise to stay out of the way invokes, before quaintness or quirkiness, a kind of disavowed ambition, a desire to exert non-diegetic influence by becoming continuous — to the point of self-directed obsolescence — with the real thing.

Shirl Yang is a Humanities Teaching Fellow at the University of Chicago. Her first book project is on the aesthetics of economic non-participation — not working, not consuming, not investing — in 20th and 21st-century popular culture.

References

- Hayley Maitland, "The Founder of Hinge Has Some Thoughts on Your Dating Profile," Vogue, April 12, 2019.[⤒]

- Nancy Jo Sales, "Can Hinge Make Online Dating Less Apocalyptic By Losing the Swipe?" Vanity Fair, October 11, 2016.[⤒]

- Amar Toor, "Tinder throws a Twitter fit over Vanity Fair article," The Verge, August 12, 2015. [⤒]

- "What We Believe," Hinge.co, accessed February 17, 2020.[⤒]

- "Hinge, the Dating App Designed to Be Deleted," YouTube, Aug 12, 2019.[⤒]

- How We Do Things (Hinge, 2021), 23.[⤒]

- Hinge is far from alone in its appeal to a deflated mediation: critics writing on cultures of "new" sincerity have often noted that texts or objects concerned with sincerity often make some gesture of cancelling out the medium they are couched in, via forms of mediation that don't quite seem to work, feel outdated, or, as in the case of Hinge, hate themselves. See, for instance, Ellen Rutten's Sincerity After Communism: A Cultural History (New Haven: Yale University Pres, 2017); Jim Collin's "Genericity in the Nineties: Eclectic Irony and the New Sincerity," in Film Theory Goes to the Movies, edited by Jim Collins (New York: Routledge, 1993).[⤒]

- For examples, see the "Bitch Better Have My Money" app from season 1, episode 3 of Terrence Nance's Random Acts of Flyness, or Miranda July's short-lived "Somebody" app.[⤒]

- The Modern Love episode mythologizing McLeod's own real-life love story plays out this subliminal anxiety about what counts as "real" connection. The episode opens with McLeod's stand-in (played by Dev Patel) being interviewed about Hinge by a journalist (played by Catherine Keener). But the actual story — about two people who have both ostensibly missed the people they were meant for — pointedly takes place after the cameras and tape recorders have been put away and it's "just" two people trading stories about their missed romantic encounters. As if anxious about the second, more organic interaction being tainted by the initially transactional nature of the meeting, the episode follows the two characters as they change locations several times during their heart-to-heart (moving from a conference room to a park bench to a coffee shop) — putting physical and temporal distance between the two modes of encounter.[⤒]

- Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, "Dogme 95: The Vow of Chastity," in Technology and Culture: The Film Reader, ed. Andrew Utterson (Oxford: Routledge, 2005), 87-88.[⤒]

- Danny Paez, "How a Beloved Video Game Was Spawned Out of Necessity: '8-Bit,'" Inverse, Oct. 25, 2020.[⤒]

- Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002); Laura Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002). [⤒]

- Marks, Touch, 148.[⤒]

- Marks, Touch, 211.[⤒]

- Jenny Sundén, "Technologies of Feeling: Affect Between the Analog and Digital" in Networked Affect, eds. Ken Hillis, Susanna Paasonen, and Michael Petit (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015), 135-150.[⤒]

- Massumi, Parables,138. [⤒]

- McKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007).[⤒]

- Pixelated Noose, "Toby Fox Camp Fangamer Interview (Part 2)," YouTube, March 16, 2018.[⤒]

- While sharing a sense of the problem, studies of American loneliness invariably vary in their specific diagnoses. David Foster Wallace's 1993 "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction" is interested in loneliness in the context of spectatorship and a culture of irony — one in which people have been trained by television to prefer observing the world to being implicated in it. Robert Putnam's widely discussed Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000)focuses in turn on a decline in civic engagement — the decline in bowling team memberships is his first example. We might also add to this collection sociological studies of American "character" like Riesman, Glazer, and Denney's The Lonely Crowd (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950), Philip Slater's The Pursuit of Loneliness (Boston: Beacon Press, 1970), or Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swindler, and Tipton's Habits of the Heart (Berkeley: University of California Press: 1985).[⤒]

- Adrian S. Franklin, "On Loneliness," Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 91, no. 4 (2009): 343-354.[⤒]