Little Magazines

" . . . exploring coloration and penumbra

light-wise coloration magnifies what I see

and eclipse coloration here dense pitch dense

beauty all light your halo

opened out of darkness your good dense form

fiercely dark

in this pure instant's output

receives my eyes as my nose receives your incense

and my hands assemble touch

the darkness

and mumble-enamor-intense elating

-Coloration Penumbral We love you-"

— Lloyd Addison, "The Poet Talks to a Face and the Face Talks Back," Umbra Vol. 1 No. 1, 1963

Imagining the small press communities of '60s New York, one thinks of a network of nodes, each node itself a network of associations, friendships, influences, and lineages. The group known as the Society of Umbra, and the Umbra magazine that emerged from this group, is one such dense node. The poets, writers, artists, and activists who came together briefly as Umbra brought with them direct lineages from the Harlem Renaissance; they also brought firsthand accounts of the contemporary movements to end Jim Crow segregation in the South. After Umbra's brief and brilliant existence, its members went off to indelibly shape American poetry and civil life. I would like to focus here on the first issue of their little magazine, and more specifically on just a few of that first issue's contributors,1 with the aim of conveying (at least some) of the story of this remarkable node of American poetry through the presence of David Henderson and Langston Hughes, and the lesser-known poetic contributions of Julian Bond and Leroy Lucas. Henderson, who still lives in lower Manhattan and whom I've known for many years, was generous enough to speak with me about Umbra's history for this essay.

The Society of Umbra, a Black literary collective formed during the Civil Rights era, came together in the Lower East Side in 1962. The poets of Harlem, which had been the geographic centrifuge of Black literature in New York, had a role in Umbra's genesis. Before the workshops that eventually became Umbra were taking place on the Lower East Side, these poets were participating in a series of literary gatherings that were first held at the Market Place Gallery and Bookshop, located on Seventh Avenue in Harlem, in 1960. The readings featured the poet Lloyd Addison, Roland Snellings (later Askia Touré), and the work of Calvin Hernton.2 According to Henderson, an older group of writers made appearances at these Market Place Gallery readings to "give the younger poets models for how it was done." These included the poet and librettist Raymond R. Patterson and the playwright Oliver Pitcher.

The particular younger generation of Black writers that included Henderson and Hernton, however, were moving away from Harlem both geographically and ideologically. Creating a culture and ethos for poets to thrive outside of any previously existing literary "establishment" was central to Umbra's mission. The decision to gather on the Lower East Side instead of Harlem was primary to this break from tradition. In 1962, the New Orleans poet Thomas Dent, who had recently moved to the LES, invited a number of young Black writers to convene at his apartment on East 2nd Street, including Henderson and Hernton. Dent wrote for the well-known Black weekly newspaper The New York Age, worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and was a passionate champion of other Black writers. The group began to hold weekly gatherings on Fridays to read each other's work, meetings full of rigorous critical intensity and enthusiasm. They realized they needed a name for the collective that was forming and chose "Umbra" from a line in a poem by Addison.3 As the group continued to share writing and ideas, they recognized the need for a public presence, and so they decided to put out a magazine in January of 1963 and host a corresponding public reading series. Umbra would feature Dent as editor and Henderson and Hernton as associate editors. Henderson had turned 20 years old the previous Fall, and was working for District 65 of the AFL-CIO, fighting to raise the minimum wage to $1 an hour.

Langston Hughes, the abiding Harlem Renaissance poet, was an early friend and champion of Umbra despite the group's desire to distance itself from the literary mainstream. Hughes was well-known for the kind of championing of up-and-coming writers that he extended to Pitcher. According to Henderson, both Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks had "a mission to discover young Black poets" and wanted to support the writers who formed Umbra. When Hughes heard that Henderson and other poets had started a collective and magazine, he gave Henderson his mailing list, granting the Society of Umbra access to his circle of writers and editors. When the first issue of Umbra was printed, the editors sent it to everyone on Hughes' list. Recipients responded enthusiastically, bought subscriptions, and joined Umbra's mailing list.

Hughes was also significant to the Umbra poets as a literary innovator, especially his hybrid text Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz (Knopf, 1961). Henderson considers Ask Your Mama Hughes's masterpiece. In conversation, he told me that he had the book out on his table and had just been reading it that day. Ask Your Mama exploded the limits of what had been done with sound, typography, and space on the page; this push at literary conventions functioned as a model for the Umbra poets, who were also interested in crafting experimental poems that were overtly political. Nevertheless, though it was deeply intertwined with Hughes and Harlem, Umbra would, for its brief and powerful lifespan, remain a Society on the outside, firmly rooted in lower Manhattan and in a radical, anti-establishment political ethos.

Umbra's formation was a move away from the kind of tokenism of Black writers that pervaded New York literary circles. After the initial printing of Umbra magazine in early 1963, a few more poets joined their ranks: Lorenzo Thomas, Ishmael Reed, and the "transrealist"4 poet Norman Pritchard. They hosted public readings at St. Mark's Church In-the-Bowery, among other places, where eight or more poets would read. Michel Oren writes that "during Richard Wright's time, there had been single Black writers who had successively held the public eye as representative of 'the Black writer,' but [Umbra] rejected this sort of tokenism."5 A clear stance against the literary critical establishment's expectation of Black "spokesmanship" is foregrounded in the foreword to Umbra Vol. 1 No. 1: "We do not exist for those seemingly selected perennial 'best sellers' and literary 'spokesmen of the race situation' who are currently popular in the commercial press and slick in-group journals."6 Instead of continuing a model of singular Black genius that had arisen out of white literary traditions, Umbra would create a space for Black genius to be shared, collective, and impossible to contain. Their magazine precisely embodies this radical entanglement.

***

The first issue of Umbra, published in January 1963, carries a distinct formal arrangement that makes it clear these poets saw the medium of the little magazine as a collectively wrought body of work rather than a collection of unrelated poems by various poets. The magazine's 46 typewritten, offset printed pages are grouped into four sections: "Figurine of the Dream/Sometimes Nightmare," "Blues and Bitterness," "Time and Atavism," and "Umbra Through Ethos." The first Umbra includes the work of sixteen contributors, some of whom have multiple poems in different sections of the magazine. The structuring of these sections is evocative and intentional; as the magazine's foreword states, "Umbra is not another haphazard 'little literary' publication."7 Though printed in a small edition, every element of the publication's content resists littleness or haphazardness, offering instead a portrait of a community rigorously committed to political, social, and imaginative freedom.

The two-page foreword to the first issue, collectively authored by the magazine's editors, directs the reader in clear terms: "Umbra has a definite orientation: 1) The experience of being Negro, especially in America; and 2) that quality of human awareness often termed 'social consciousness.'"8 What's contained within the scope of "social consciousness" here is quite dazzling. The poems (and one play excerpt, by Pitcher) range widely and wildly, from song-like lyrics to conversational verses to cryptic single-sentence utterances to highly disjunctive jazz notes. Political and social consciousness is always present in the work. Reading these poems with an awareness at the forefront of my mind — that Umbra's tacit orientation is toward the lived experience of Black Americans — I find myself asking whether a reader can see the evolution of discourses of Blackness, especially in the 1960s, through these poems. "Discourses of Blackness" can mean many things, but here I mean the creation of new frameworks, specifically attuned to contemporary political possibilities and transformations, for Black writing.

This is, of course, a huge question. As a white scholar with a regard for Black poetry that's more poetic-intuitive than academic, I'm not sure I can answer this question directly. Reading the pages of the initial issue of Umbra, however, I find myself curious to read these poems against the backdrop of related discourses, related movements: the Civil Rights Movement, the evolutions of Beat and New American poetry ("being beat down," interestingly enough, is the first line of the first poem in the magazine, by Thomas Dent).

Umbra offers a frank profession of respect for difficulty, and a recognition of the essential role that "difficult" writers play in a broader social ecosystem. "Umbra exists to provide a vehicle for those outspoken and youthful writers who present aspects of social and racial reality which may be called "uncommercial' 'unpalatable' 'unpopular', 'unwanted,'" the foreword states, "but cannot with any honesty be considered nonessential to a whole and healthy society."9 The contributor's biographies at the end of the magazine note each of the sixteen contributors' ages: Lorenzo Thomas, at 18, is the youngest, while Oliver Pitcher, at 39, is the oldest. The fact that none of the contributors was over 40 speaks to the "youthful" element of the credo in Umbra's foreword. More interesting than the contributors' ages, however, is the way that the magazine allows us to trace these poets in their own trajectories at this particular moment in time. Winter of 1963 was, of course, a critical point in United States history.

The second poem in the issue is by Julian Bond, 23 years old at the time. Titled "#3," it reads in full:

At the moment this verse was published, King was only a few months away from beginning his campaign against Jim Crow segregation with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Birmingham, a watershed both for King and for the Civil Rights movement. Bond, who had at this point left the historically Black Morehouse College in Atlanta to work full-time as a civil rights organizer in Georgia, went on to become one the most influential social activists of the century, co-founding the Southern Poverty Law Center and serving as the chairman of the NAACP.10 Here, the young, already-worldly Bond, speaking as poet, makes a startling two-line declaration. There's a casual pleasure in the acknowledgment that "we can't all be Martin Luther King," but that pleasure is tinged with so much else: affection for King himself, outrage at the expectation that "we all" should be King-like, a corresponding breach with politeness in the form of blatant voyeurship ("look at that gal shake that thing").

Bond's other three poems in Umbra, "Ray Charles, Bishop of Atlanta," "Miles," and "Langston Hughes" each make a study of a Black cultural icon. Each poem is short, 12 lines or less, and offers a pithy gloss on the musician or poet that's both complicated and celebratory. Bond's poem about Hughes:

LANGSTON HUGHES

He writes about Jesse Simple and home folks

in Harlem,

Biggity people read his stuff and frown,

Depressed,

They just don't like to see themselves

With their souls undressed

Bond's poem makes a slant declaration of admiration for Hughes, turning to him as a revealer of uncomfortable truths. I read this poem in light of the question of how Umbra addressed discourses of Blackness in 1963: Bond, a young activist and soon-to-be politician, doesn't necessarily praise Hughes. Instead, he uses the space of the poem to make a sort of riddle, a space in which it's not immediately obvious where his sympathies lie. Does Hughes's Harlem "folk philosopher" Jesse B. Semple speak of the true, naked souls of Hughes's skeptical readers? Is Hughes's folk philosophy a false caricature of Black life? Who, in Bond's view, is the speaker of the truth? The questions raised by this poem track with Umbra's statement about their political stance: "We are not a self-deemed radical publication; we are as radical as society demands the truth be."11

***

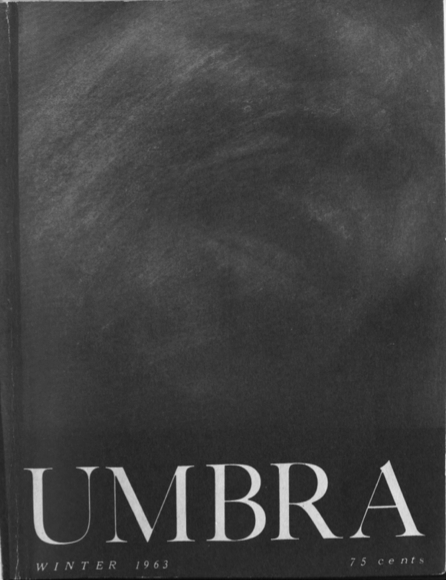

The image on the cover of the first issue of Umbra is a drawing by the artist Tom Feelings, a member of the collective. The image is of a Black man's face that appears to be in motion, eyes closed, mid-utterance or mid-ecstasy. Other than Feelings's cover, the work of one other visual artist appears in the pages of Umbra Vol. 1 No. 1: that of Leroy Lucas (then Leroy McLucas), a filmmaker and photographer. The magazine includes four poems by Lucas: "Bana," "Negotiation," "Kicks," and "Graph." Lucas, 28 at the time of the magazine's printing, was a documentary photographer and filmmaker. As Umbra was going to print, Lucas was working on The Cool World (1963, dir. Shirley Clarke), a "semi-documentary" film about youth gangs in Harlem.12 The film was shot by Lucas on location in Harlem, and used amateur and first-time actors from the neighborhood.

Lucas's poems in Umbra are dense, spare, idiomatic pieces of language, and convey a vividness not unlike his photographs and film stills. They offer concentrated moments of vernacular life, as in "Kicks":

"Kicks" has the quality of something overheard, a fragment of narrative that pulls meaning into itself. Rhyming words share multiple valences: "fourteen" points to 14th St., a primary Lower Manhattan artery, while "clean" invites a whole host of implications, from the racialized labor of janitorial work ("mop bitches floors") to racialized stereotypes of drug and alcohol use. "Kicks" refers most obviously to shoes. But it also points to thrills, diversions, as well as to violence, to literal or metaphorical kicking. The Stacy Adams brand of men's footwear — a staple for Black men made popular in the 1940s by musicians like Cab Calloway and further championed in the '80s by Morris Day — appears beside "knob toes / a month's slave." I picture a pair of shining square-toed shoes that might have cost a month's wages, and all the conditions that converged to make those shoes appear in this utterance.

The last of Lucas' four poems, "Graph," is an abecedarian:

Armfull bedwork carbonized

delinquent ejaculation

fornicated ghetto

hardbound idiom

jackass jacknife jackoff jackscrew

jailbird jaywalker jazzer jeer jesse

jame jitterbug jobseeker john

joiner joggler juggler junkman

knottyknight leaseless lofer

muddymule nightnymphs

uprooted pantaloon

quarter rubber stamp

tenderfootin umbrella

vaginal woebegone

x yesman zulu13

Lucas's "hardbound idiom" in this poem is also intensely visual. The language moves between images of Black urban life that are cultural clichés ("fornicated ghetto"; "jobseeker john") and jubilant wordplay ("muddymule nightnymphs / uprooted pantaloon"). The poem seems to reclaim words used by the racist white mainstream to describe Black "delinquency" — jackass, jailbird, jaywalker, jobseeker, juggler — for its own purposes. The poem moves, for the most part, through the alphabet, giving it the quality of a catalog — a document of something in its completeness. The exception is the word "uprooted" in the place of "o," a departure that points to the ruptures created by uprooting. The "X" in the final line puts me in mind of Malcolm X, who began using "X" as his surname in 1950 in place of the slaveholder surname he'd been given at birth. Like x/X, "Graph" is a poem that refuses familiar significances, making instead an entirely new sonic/visual space.

When I was first looking through the pages of Umbra Vol. 1 No. 1, Lucas's name leapt out at me: I had seen his photographs in another context. In 1965, Lucas accompanied his friend, the poet Ed Dorn, on an epic trip through the American West. The pair traveled throughout the region that had once been the purview of the Shoshonean tribes, through the Nevada and Utah deserts and into mountains of Colorado, Wyoming, and Dorn's home state of Idaho, stopping in reservations and spending various periods of time with the Indigenous people they met there. The conversations, rituals, villages, parties, livestock, landscapes, ceremonies, and lifeways the pair encountered on their trip are gathered in Dorn's essays and Lucas's photographs in the remarkable book The Shoshoneans: The People of the Basin-Plateau.14 The phenomenon of a white poet and a Black photographer documenting Indigenous communities in the thick of the Civil Rights Movement (not to mention the American war in Vietnam) is remarkable. After reading these densely wrought lyrics of Lucas's in Umbra, I see his photographs in The Shoshoneans differently: Lucas's "hardbound idiom," in both poems and images, is one capable of conveying a rich, inscrutable story in a few words, a single gesture.

***

David Henderson grew up in Harlem, although he's lived for years in lower Manhattan. His first job in high school was as a page at the New York Public Library branch in Harlem. It was there that he initially encountered the writings of Richard Wright and Langston Hughes; not long after, he would meet Hughes, and share a friendship with him for the rest of Hughes's life. More than any of the other Umbra poets, Henderson embodies the vital tension between the Black literary traditions of Harlem and the radical innovations that occurred in the LES.

The Society of Umbra in its original form disbanded at the end of 1963 after a second issue of the journal had been produced. Henderson, however, continued editorship of the Umbra project into the '70s, editing Umbra Anthology 1967-1968, Umbra Blackworks (1970), and Umbra Latin/Soul (1974, co-edited with Barbara Christian and Victor Hernandez Cruz). Umbra's members moved on to make other movements happen, all of which contributed to the Black Arts Movement. Askia Touré joined Amiri Baraka in Harlem at the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. Ishmael Reed founded the Before Columbus Foundation in California. Tom Dent worked with the Free Southern Theater and Congo Square Writer's Union in New Orleans.

These are only a few of the many groups that emerged out of Umbra.

To talk about Umbra's crucial role in New York's literary ecosystem with Henderson, who was instrumental in making it all happen — and extending the moment into a movement — is a gift. Returning to the question of what the first issue of Umbra reveals about discourses of Blackness at the time it was made, I turn to the final poem in the magazine, Henderson's "Black is the Home." It's a poem that tells a tragic story, one that would seem mythological if it wasn't such a direct transmission of fact. A Black man trying to leave the South is lynched. The poem ends on an image of his body "in the shadow of the steep steep Olympus . . . a downsouth man / starved and murdered before sighting land."15 But the poem uses lofty cadences and rhyme scheme, playing freely with tropes of "canonical" English-language poetry:

In the Section of the Blacks

Amid and below

Hangs by the neck a down south Negro

Who after reading of that scroll

Forgot the desire to plant no-land

And came North seeking jelly-roll.16

The closing poem of Umbra Vol. 1 No. 1 is nothing if not true to Umbra's stated mission that the magazine "exists to provide a vehicle for those outspoken and youthful writers who present aspects of social and racial reality which may be called "uncommercial' 'unpalatable' 'unpopular.'" I think of the young Henderson writing this poem, typing it up, reading it on a Friday evening among friends, knowing its subversion in the face of all that was happening in the United States at that moment. The embrace of this subversion is what I'd like to celebrate: it laid the ground for so much else, and as it happened, it was beautiful.

In the magazine's foreword, the editors declare "an unequivocal commitment to material of literary integrity and artistic excellence."17 As a reader, I find myself drawn to respond to this sincere commitment by committing in turn: to studying a little magazine like this cover to cover, to attending to its physical particularities as much as to its historical context. Turning the pages of Umbra Vol. 1 No. 1, I find myself entering the world in the moment this magazine came into someone's hands. It's a world in which the messages communicated in Umbra were of vital, transformative importance. These poems became singular through the medium of those pages; the reception of the Umbra poems would fix the reader in time and space in a way that is too often lost to readers now. Studying a single issue of a magazine closely like this makes for a subversive reading practice; it pushes me into this singular space. The provisional, radiant community of Black writers that gathered in 1963 created this space, building within it complex temporalities and visions for liberation. Reading Umbra closely grants momentary entry into that world.

Iris Cushing is a poet and scholar living in the Catskill mountains. Her poems and critical writings have appeared in Granta, Fence, and the Academy of American Poets Poem-A-Day series. She is the co-editor, with Jason Weiss, of Mary Norbert Korte's Jumping into the American River: New and Selected Poems (Argos Books/TKS) and the author of The First Books of David Henderson and Mary Korte: A Research (Ugly Duckling Presse) and Wyoming (Furniture Press Books).

References

- Numerous excellent chapters and books exist about the Society of Umbra. These include Lorenzo Thomas's "The Shadow World: New York's Umbra Workshop & The Origins of the Black Arts Movement," Callaloo, no. 4, (October 1978): 53-72; David Grundy's A Black Arts Poetry Machine: Amiri Baraka and the Umbra Poets (Bloomsbury, 2019); and Daniel Kane's All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s (University of California Press, 2003). [⤒]

- Hernton had temporarily left New York City to teach at Edward Waters College, a Black college in Florida; another poet read Hernton's work at the Market Place Gallery. These details come from my conversations with Henderson, and from Michel Oren's "A 60s Saga: The Life and Death of Umbra," in Freedomways 24, no. 3 (1984).[⤒]

- See Lloyd Addison's The Aura and the Umbra, 1970 8 in the Heritage Series (Paul Breman, London).[⤒]

- Oren, "A 60's Saga," 174.[⤒]

- Oren, "A 60's Saga," 169.[⤒]

- "Foreword" in Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963). The Umbra journal is archived at the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.[⤒]

- "Foreword," Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963):3.[⤒]

- "Foreword," Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963):3.[⤒]

- "Foreword," Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963):3.[⤒]

- See Julian Bond, Race Man: Selected Writings 1960-2015 (City Lights, 2020). In addition to his work with the SPLC and NAACP, Bond was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1965. In 1966, Georgia representatives voted not to seat Bond, in response to his public support of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee's opposition to the war in Vietnam. After winning a Supreme Court case over his unseating, Bond served on the Georgia State legislature for four terms, from 1967-1975. Bond also ran — and lost — in a tight race against John Lewis to represent Georgia's 5th Congressional District in 1986.[⤒]

- Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963): 3.[⤒]

- See Daniel Eagan's essay on The Cool World in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry (Bloomsbury Academic, 2010), 600-601. [⤒]

- Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963): 39.[⤒]

- Ed Dorn and Leroy Lucas, The Shoshoneans: The People of the Basin-Plateau (University of New Mexico Press, 1966).[⤒]

- Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963): 44.[⤒]

- Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963): 44.[⤒]

- Umbra 1, no. 1 (1963): 4.[⤒]