Little Magazines

"The school of Boston in poetry, middle this century," wrote Gerrit Lansing in 1968, "is an occult school, unknown."1 For this school, comprised of the poets Jack Spicer, Robin Blaser, John Wieners, Joe Dunn, Ed Marshall, Stephen Jonas, and Lansing himself, little seems to have changed half a century on. As with many such endeavours, the most regular gatherings of this group took place over a relatively brief period. Initial activity in Boston, from roughly 1953 to 1956, culminated in the publication of the ephemeral Boston Newsletter and the initiation of Wieners's little magazine Measure. A second stage takes place largely in San Francisco through to the turn of the decade, with a continuing presence maintained in New York and Boston through the 1960s, most notably in Lansing's magazine Set. The publications of the "Occult School" reveal a queer, working-class presence in the New American Poetry, well before Stonewall, and distinct from the more urbane aesthetic of the early New York School. These works take their place alongside the nascent "homophile" activist groups, the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, and the magazines One and The Ladder. And in turn, they anticipate and influence an equally neglected explosion of queer anarchist publications following Stonewall: Fag Rag, Gay Sunshine, Lavender Vision, and the Good Gay Poets press.

A school without institutions, a curriculum, or any one central teacher, operating in the shadows, the story of the Occult School begins with the meeting of Stephen Jonas and Edward Marshall on Boston Common in 1953. Jonas, whose propensity for spinning multiple yarns about his origins dovetails with gay men's use of multiple names as protection from legal retribution, was likely born as the African American Rufus Jones, in Georgia.2 Obtaining a medical discharge from the Air Force, he was part of a queer bohemia surrounding legendary Boston gay activist Prescott Townsend, discovering modernist poetry through a local radio show by poet Cid Corman, whose writing group he attended. In turn, furnished by a book and record collection partially stolen from the public library, his own apartment became a kind of informal academy for the junkies, sex workers, petty criminals, and poets who were his friends. Marshall, meanwhile, had been born into the Marshalls of the Marshall's Fruit Stand company. His mother having been institutionalised when he was a baby, he'd himself ended up in the same hospital after a teenage breakdown. When he met Jonas, he was a twenty-year-old student, visiting Boston at weekends. Jonas recalled the occasion:

O how well I can recall that day from your white mountains you arrived to me (spirit sent) upon the mid-entre gate to the queens gardens holding out to me those T S. [Eliot] poems and I shouted louder than your own black Webster — dan'l — "Hell, man you've got to SEE the thing."3

Equally devoted to religion, poetry, and homosexuality, it's unclear if this meeting was an act of cruising, of open-air preaching, a poetry recital, or all three. Either way, the two soon moved in together, Jonas mentoring Marshall in poetry and life, encouraging him to shoplift Lorca translations in the tradition of "Mercury, patron to thieves & poets."4 Under Jonas's tutelage, Marshall wrote rangy, intense poems, most notably "Leave the World Alone," which later caught the attention of Charles Olson, appearing in the Black Mountain Review and Donald Allen's The New American Poetry. A poem of local and family history, "it's like the whole god damned back country started talking," Olson proclaimed.5

At a reading by Olson at the Charles Street Meeting House the following year, Jonas encountered two more younger writers, newly graduated from Boston College. Born in suburban Milton, John Wieners avoided the military draft by declaring his homosexuality, and, following his graduation from Boston College, moved with his boyfriend, Dana Durkee, into an apartment in Beacon Hill bohemia. His classmate Joe Dunn, though straight, "swished" in imitation of his friends; the two were immersed in poetry and emerging from a Catholic education into the city's bohemia.6 Wieners already knew Jonas from the city's gay scene; after Olson's reading, the three stayed up all night talking, and were soon holding weekly poetry meetings at Wieners's apartment. Wieners, Joe Dunn, and his wife Carolyn Dunn soon followed Olson to Black Mountain College, where Wieners' poetry blossomed. When the College closed in 1956, he and Dana moved into the same apartment building as Jonas. And though Marshall had departed for New York, the arrival of two Berkeley poets led to a renewed burst of activity.

At the turn of the previous decade, Jack Spicer and Robin Blaser, along with Robert Duncan and Landis Everson, had formed what they called the "Berkeley Renaissance." Studying with medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz, they were captivated by Kantorowciz's personal acquaintance with the queer cult surrounding the German poet Stefan George — a somewhat dubious collective later satirised in Rainer Werner Fassbinder's film Satan's Brew — and envisaged a new queer literary movement of their own. When Kantorowicz refused to sign the McCarthyite "Loyalty Oath" imposed on California state employees, Spicer followed suit; he and Blaser also attended local meetings of the Mattachine Society. Spicer's refusal to sign the oath had badly affected his chances of an academic career, and in 1955 he departed for New York. The city's gay bohemia was not to his liking: as his letters of the time reveal, he found the poets of the New York School too urbane and camp — "no violence of the mind and no violence of the heart, no one screams in the elevator" — and followed Blaser to Boston, where both found library jobs, Blaser at Harvard, Spicer at the Boston Public Library.7

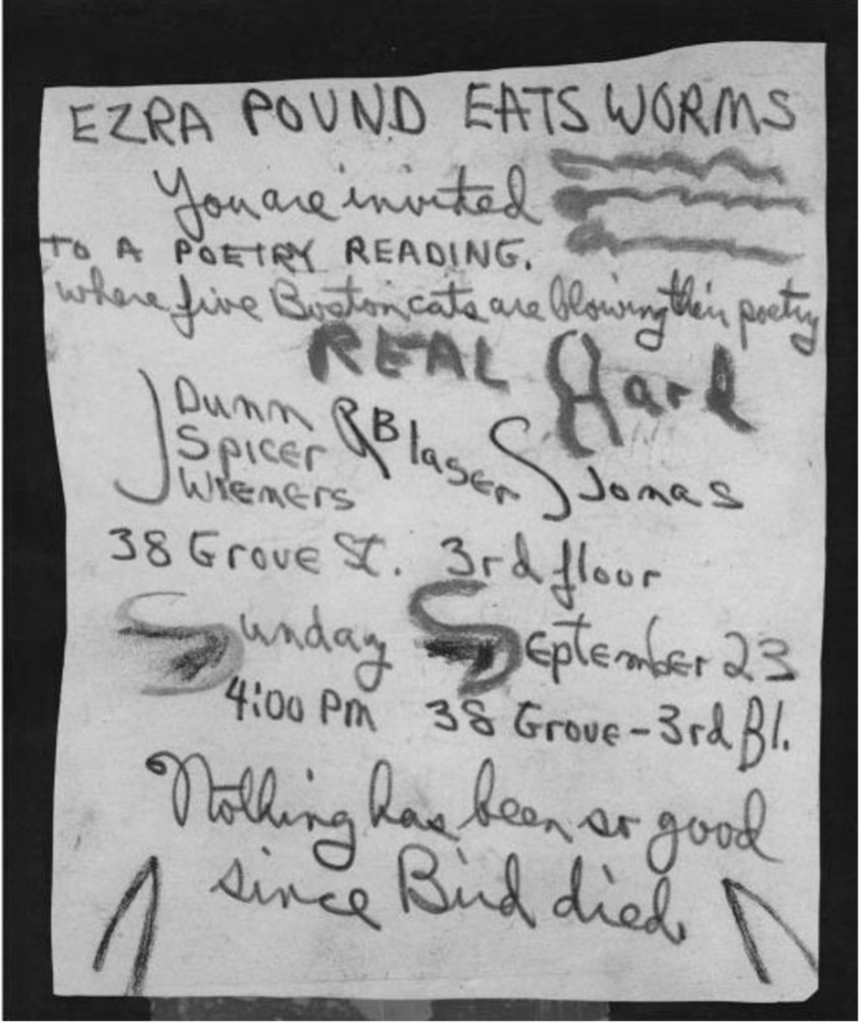

The Boston poets were, it could be said, everything the New York School in the 1950s and the Berkeley Renaissance in the 1940s were not: working class, defiantly underground, equally devoted to poetry and to Beacon Hill bohemia. During a single summer, the five poets met, talked, and shared work incessantly. In September 1956, Spicer designed a poster for a reading given by the five poets, proclaiming "EZRA POUND EATS WORMS." The following month, the "five Boston cats" produced the staple-bound, one-shot Boston Newsletter.

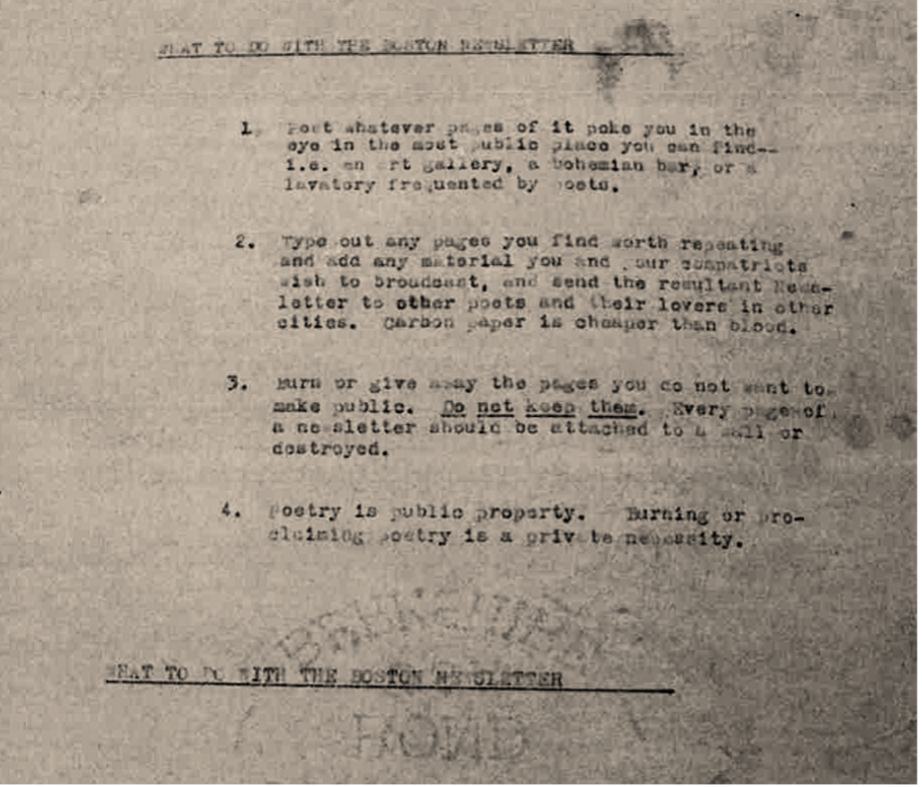

Ironically named for the first continuously-published newsletter in British America, the Newsletter was defiantly ephemeral. There are no distribution lists, no subscribers, and few remaining copies. Instead, the Newsletter served as a way for the "Occult School" poets to declare their identification to and for each other, establishing a paradoxical form of open coterie. Taking a leaf from the clandestine methods by which One and The Ladder made their way round the country's newsstands, it was published with a set of instructions for distribution "in the most public place you can find — i.e. an art gallery, a bohemian bar, or a lavatory frequented by poets." The phrasing wittily illuminates the dilemmas of building a poetic movement whose sociality was imagined through a then-illegal activity — gay sex — asserting both that "poetry is public property" and that "burning or proclaiming poetry is a private necessity."

In the environment of the Red and Lavender scares, when the police visited Jonas's apartment looking for drugs, advising him to destroy his collection of gay porn, while queer writers were subject to a series of high-profile court cases, most notably the "Howl" trial (which Spicer attended on his return to San Francisco) and the prosecution of Amiri Baraka and Diane di Prima's The Floating Bear for queer content in 1961.

And if the Newsletter's editorial material is witty, the poems within it are often haunted. Wieners first read "Ballade" to Spicer and Frank O'Hara "in the humid summer evening of Beacon Hill" while "the both of them wept through the incipient rain and electric-charged air."8 He'd re-dedicate it to Spicer on the latter's death, ten years later. The poem concerns a twenty-year-old drag queen named Alice O'Brian who either commits suicide or is murdered in a jail cell. Likewise, "That Old Gang of Mine" — better known as "Hart Crane, Harry Crosby" — emerged from a ferry ride Wieners took with O'Hara to visit Edwin Denby in Provincetown, the two "th[inking] of suicide as the final resolution of our desire, . . . speaking of Hart Crane and the last words we would have in our mouths at that moment of surrender."9 Spicer's own "Goodnight," included in a notebook alongside drafts for the Newsletter but only published this year, addresses discourses of queer martyrdom with a more sceptical eye, presenting them as a series of double-binds necessary for the creation of queer poetry but which queer poetry would have to move beyond.10

Spicer returned to San Francisco soon after, followed by the Dunns. Here he completed the project he'd begun in Boston, the epistolary sequence After Lorca, the first instance of what he called the "serial poem." Emerging from collective dialogue of the Newsletter, in which poets pick up each other's threads, it was a way to balance the agonies of personal love and the figure of the "outside" or "dictated poetry" — a course he'd follow until his death in 1965 in the context of the "Spicer Circle," a coterie of younger poets who gathered round him in San Francisco bars and parks, talking incessantly of poetry, baseball, and love. Spicer's other main project was to encourage Joe Dunn to set up White Rabbit Press, its second publication After Lorca, its first a pamphlet version of a poem by Jonas that had been at the heart of the Newsletter. There titled "Michael Poem," now "Love, The Poem, The Sea, and other Pieces Examined," Boston gay activist Charley Shively later called it "one of the finest love poems in any language."11 In another poem, Jonas playfully addresses the new publication enterprise: "White Rabbit / Press on / Promiscuous and / Come again again." Jonas's poem appeared posthumously in Boston Gay Liberation magazine Fag Rag, its endorsement of non-alienated, wilfully polygamous approach to poetry and cruising the perfect bedfellow.

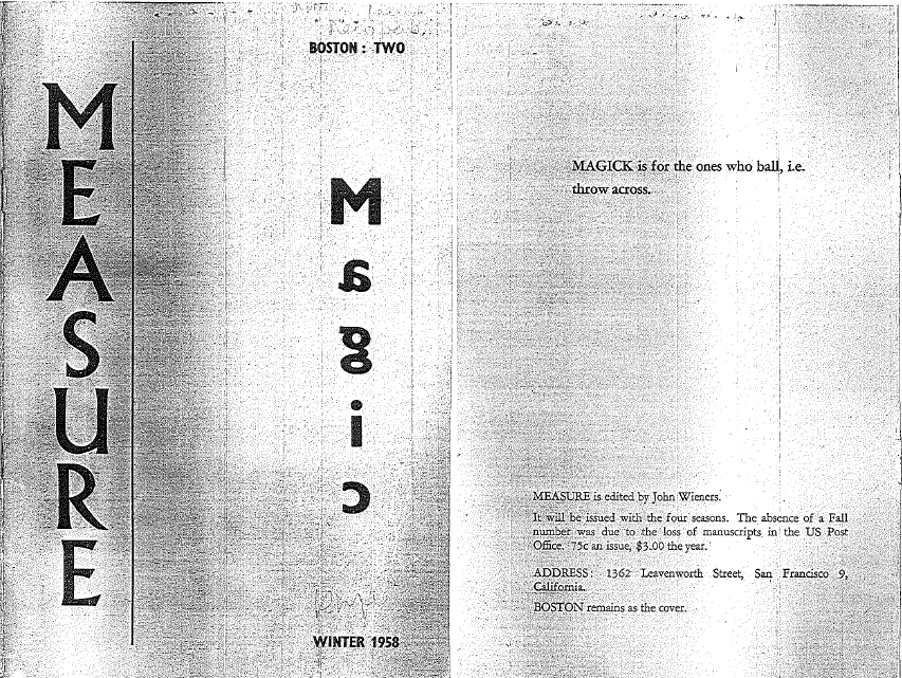

Meanwhile, Wieners conceived of a new magazine to follow through on the energy of the Newsletter: "BOSTON: a blast from," bringing together a "new generation" of poets from Black Mountain, Beat, New York, and Boston terrain.12 Armed with correspondent lists from Cid Corman, Olson, and Allen Ginsberg, Wieners also studied magazines like Charles Henri Ford's Blues: A Magazine of New Rhythms at the Lamont Library, where he was briefly employed. Just as outrageous as Ford, Wieners pursued a more markedly working-class — or lumpen — aesthetic. Quoting Rimbaud, he proclaimed in a letter to Duncan that "I alone have the key to this savage sideshow. Boston is that now. A show of junkies, cocksuckers, outriders, THIEVES." Jonas was once again an enthusiastic cheerleader, his "Word on Measure," printed in the first issue of the resultant Measure, likening poetic composition at once to a jazz "head" and a handjob. Jonas's poem appears alongside work by the other Occult School poets, as well as Olson and O'Hara. The second issue, themed around "magick," adds Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso. Even with the inclusion of V. R. "Bunny" Lang, though, the magazine remained notably male-centric.

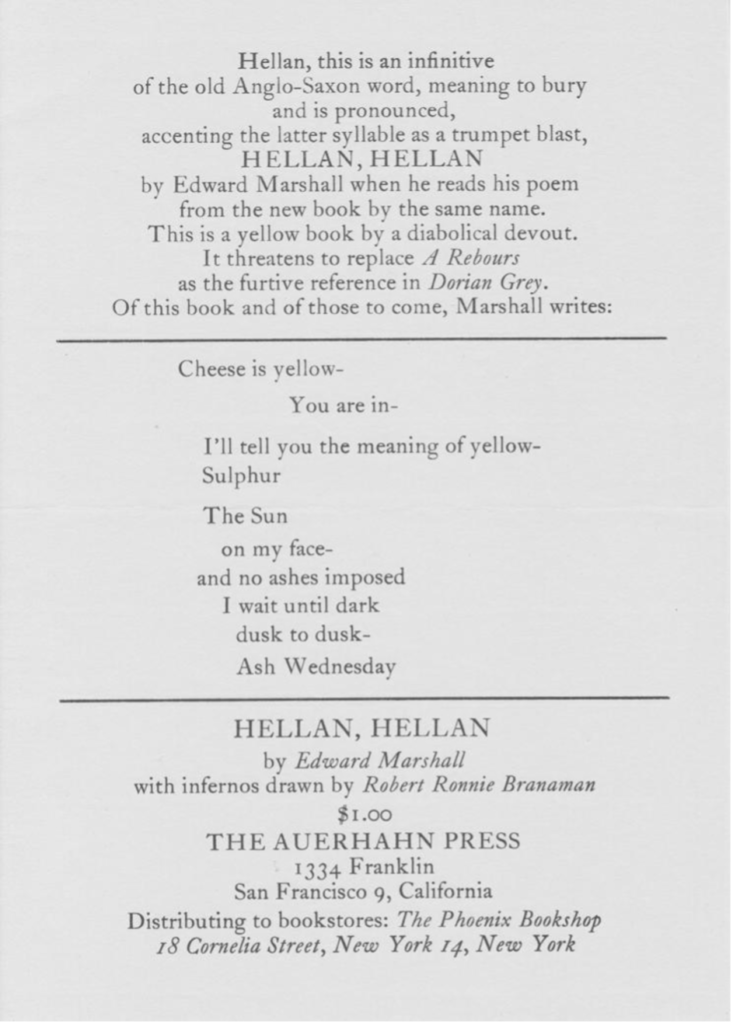

A letter from Duncan encourages Wieners to establish the magazine as a space "not of the created but the process . . . primordial, unestablished."13 In this spirit, Wieners and Dana soon followed Spicer to San Francisco. Planning a third issue on "the city," Wieners was de-railed by drug addiction, a bad breakup, and the first signs of mental illness, likely drug-induced. (The issue would not appear until 1962, adding to its roster poets like Barbara Guest and Helen Adam.) Wieners did, however, write what is arguably one of the greatest sequences in the language, The Hotel Wentley Poems, published by Dave Haslewood's Auerhahn Press. In turn, Haslewood had fallen in with Marshall, who'd also relocated to the city, oscillating between poetry, preaching, and cruising.14 In 1960, he published Marshall's debut, Hellan Hellan, its advertising framing it in a tradition of queer decadent literature from Huysmans to Wilde.

"Please find some b[oo]k stores of occult to look into if you have nothing better to do than cruise haha," Jonas joked to Marshall in a 1957 letter, and the poems in Hellan are a kind of poetic cruising: unpredictable successions of sensory experience, brief, serial revelations that disappear almost as soon as they appear.15 Aztec sacrifice, the Conquest of Mexico, and the genocidal nature of Puritan settler colonialism sit alongside obscure puns and undercover cops, seeking moments of poetic coherence and sexual initiation that offer parodical insights into what Marshall calls "the nothingness that is everything".16

Marshall and Wieners again appeared in print and in person together a few years later in a bohemian scene in New York around figures like Herbert Huncke and Irving Rosenthal, Ed Sanders's Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts and Peace Eye Bookstore, and the fringes of Warhol's Factory. A kind of proto-counterculture, like the earlier Occult School gatherings, the atmosphere was far grittier. Wieners was periodically in and out of mental institutions where he was, in effect, medically tortured for his queerness; Marshall would oscillate between enthusiastic bursts of cruising and poetry-writing and religiously-inspired "destruction kicks" in which he attempted to round up and destroy the manuscripts he'd given to friends.17

Meanwhile, Stephen Jonas had remained steadfastly in Boston, where, at the turn of the decade, the dormant collective gatherings of the Occult School received new impetus from a recent arrival. Poet and occultist Gerrit Lansing came from money. John Ashbery's tennis partner at Harvard, he soon found work at a university press in New York. Alternating between the social circuit of Broadway lyricist John La Touche, the occult circles of Count Stefan Walewski and Harry Smith, and the world of queer cruising — "talking about 'the brotherhood of man' / as I hustled, 44th St. West & Sixth" — he developed a poetics of ecstasy and revelation equally organised around queer sex and occultism.18 Having met Wieners through Frank O'Hara while visiting Massachusetts in 1956, he encountered Jonas in New York when the latter was staying with Russell Fitzgerald — a former love interest of Spicer's, and part of a circle around Samuel Delany. Moving to the home of inventor John Hays Hammond (the so-called "Hammond Castle") in Gloucester, he became close to Charles Olson and travelled frequently into Boston to see Jonas, swiftly becoming his closest confidante.

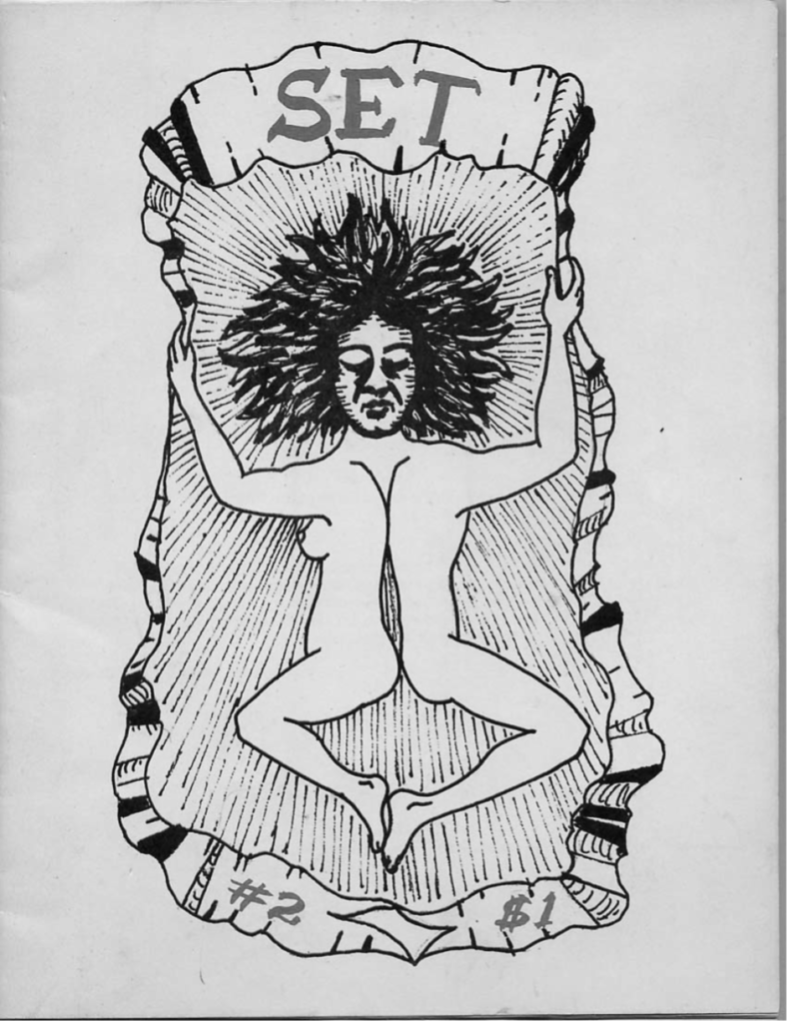

Lansing conceived of a new journal of poetry and the occult as early as 1959, reaching out to friends like O'Hara and Harry Smith, but the first issue didn't appear until 1961, with Wieners helping him find a printer after a first choice refused to print poems by Jonas and Ed Dorn for their "salty language." SET extends the concerns of Measure's second issue, which had proclaimed "magick is for the ones who ball, i.e. throw across," punning at once on baseball, the occult, and gay sex. Lansing's sprawling editorial "The Burden of SET" appears across both of the magazine's two issues, envisaging a new "Age of Aquarius" several years before Hair.

All is permitted. Change in the Heavenly Female Power. As equality of sexes swings around, the biomechanical basis of the old differentiation is shifted. This doesn't mean everyone will be 'queer', but that as new magnetic centers astrally arise in men & women the scope of both amativeness & adhesiveness will be prodigiously enlarged.19

The second issue opens with Amiri Baraka's poem "Short Speech to My Friends," in which "tenderness" and "the image, of / common utopia" contrast with racial exclusion as if in gentle rebuke to the predominantly white contributors surrounding it. Reading this poem in the context of the Occult School helps us queer Baraka, whose own novel The System of Dante's Hell was explicit about bisexual experience, and whose The Floating Bear had been censored for precisely such content, while also testing the limits of a predominantly white male movement.

The issue also contained the first four poems of Jonas's sequence Exercises for Ear, to appear as a book in 1968. Fizzing with what Lansing called "Boston lingo" — the argot of criminals, bohemians, and the queer underground, from S&M roleplay to the voices of young mothers "yak-yakking" on the street — these are criminal poems, delighting in subverting and breaking the letter of the law. Jonas also held "magic evenings" in his apartment on Beacon Hill, featuring tarot readings, jazz, and recitations, attended by everyone from young university students to poets like Lansing, Carol Weston, Robert Kelly, and, when they were in town, Wieners and Joe Dunn.

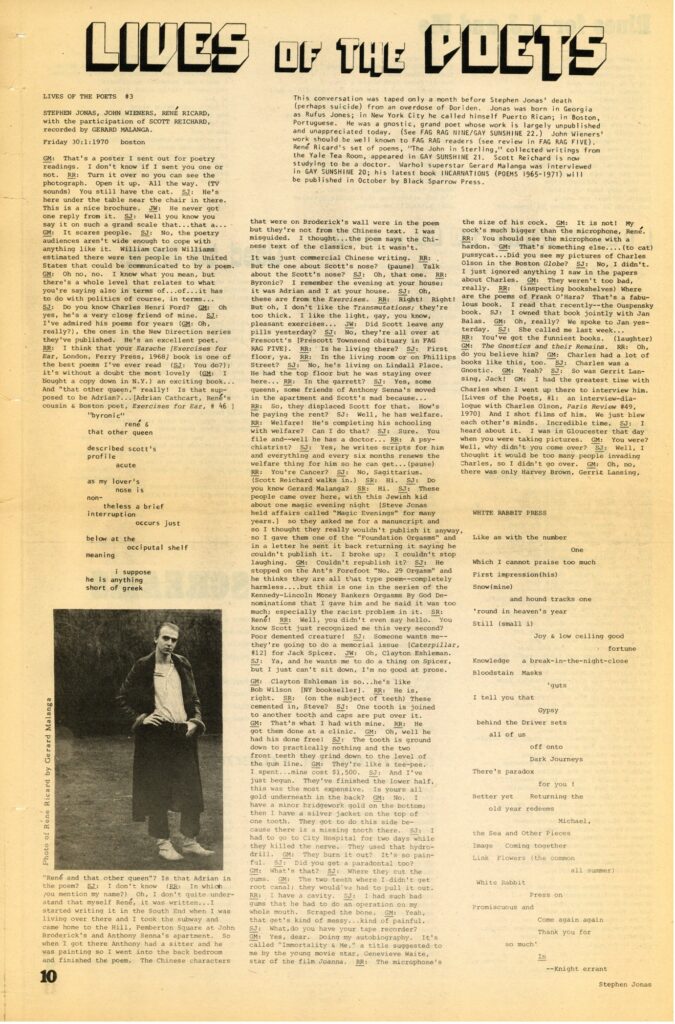

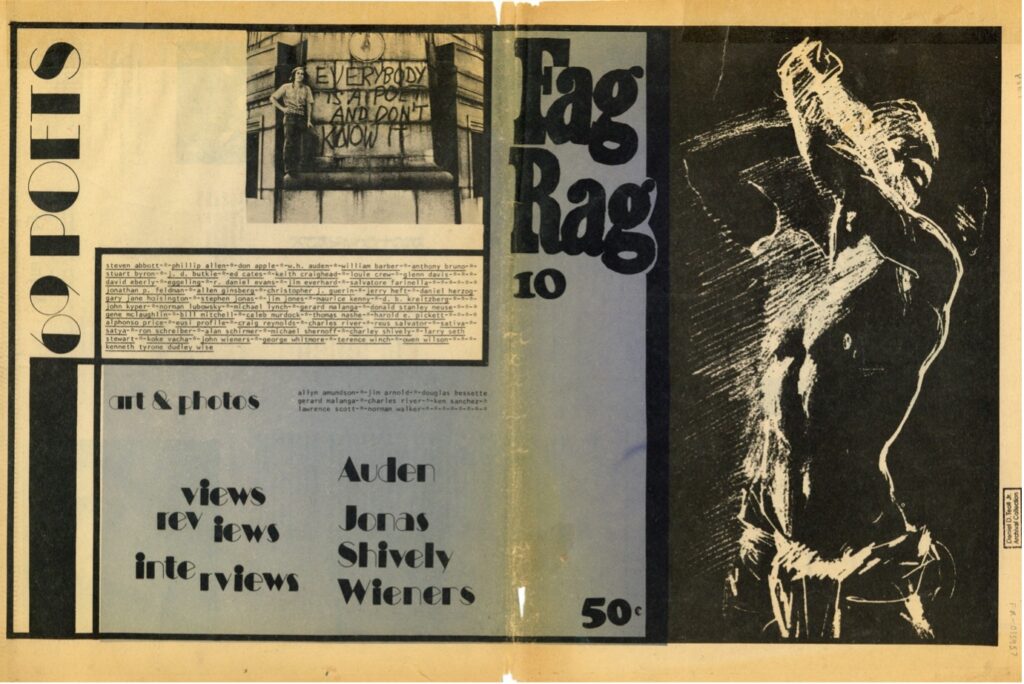

The evenings never yielded a publication; mentions are fleeting, though vivid when they appear. Apparently following the adage that a prophet is not understood in their own country, Jonas's books were all published in England through Andrew Crozier, who'd encountered Wieners while a graduate student at SUNY Buffalo in the mid-60s. Writing the preface to Jonas's first book, Transmutations, in 1965, Wieners finds in this poetry a vanished city, noting changes in the urban landscape, the "regeneration" projects of a class- and race-divided Boston, as old bohemian haunts — bars, apartments, cruising spots — disappear, leaving the traces of the poets like words chalked on a wall in the rain. Yet, as Boston's school desegregation began, and on the verge of Gay Liberation, Wieners figures the "old haunts of these poems" as "bombs to blow up in the face of the future, they have become the future itself: BLAST; in the face of emblems of the past we live by."20 Four years later, Wieners wrote to Duncan McNaughton of a kind of Occult School reunion: "Tomorrow Saturday I will go in town and meet Steve Jonas and Gerrit Lansing for their weekly Saturday evening poetry fête. Joe Dunn will also be there."21 Shortly after, Gerard Malanga and Rene Ricard recorded a lively conversation with Jonas and Wieners later published in Fag Rag's "69 Poets" issue. Witty and charming, the poets sound ready for the new decade in style.

Yet Jonas, Wieners, and Dunn all suffered from addiction and mental incarceration throughout the decade, with Jonas hit particularly hard by Spicer's death by alcoholism in 1965. Jonas and Olson died within a week of each other in January 1970; Lansing moved to Annapolis, where he underwent treatment for alcoholism; Marshall lapsed into silence, foreswearing poetry for religion. An end of a sort, this was also a new beginning. With the advent of the Gay Liberation Movement, the work of the Occult School found a new context within a set of radical queer publications drawing on the legacy of the homophile journals, countercultural newspapers, and the mimeo revolution. Through his newfound friendship with Charley Shively, Wieners would prove a central figure in the radical anarchist magazine Fag Rag and the concurrent Good Gay Poets press, who published his magnum opus Behind the State Capitol in 1975. In turn, the Occult School were a pervading influence on the San Francisco New Narrative writers and Boston poets like Eileen Myles, their spirit shooting through the pages of Gay Sunshine, Sebastian Quill, and a raft of other Gay Liberation journals.

The Occult School has not always figured in accounts of the mimeo revolution, in part because of its relatively early emergence in comparison to publications like Angel Hair and Fuck You, along with the fact that the productions were not themselves mimeographed, but sent to printers. (At Cid Corman's advice, Wieners, for instance, had Measure printed by Villiers Press in England.22) At the same time, this neglect is not a mere technicality. As Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips point out in their influential account, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: "The 'mimeo revolution,' as a term, is a bit of a misnomer in the sense that well over half the materials produced under its banner were not strictly produced on the mimeograph machine; however, the formal means of production are not as important in identifying the works of this movement as is the nature of their content."23 If the "mimeo revolution" is flexible enough a term to encompass plentiful non-mimeo publications, we might wonder if there are, in fact, broader, structural causes, to the occultation of the Occult School: causes, in this case, to do with the intersection of sexuality and class, with geographical location, and the way that these shape an experimental poetics. A parallel can be drawn to the historical neglect of the Black writers — most notably, those writers associated with the Umbra Poets' Workshop — whose activity, as Ishmael Reed and others have pointed out, was central to the New York poetry scenes around the Lower East Side that gave rise to well-known venues such as The Poetry Project, but whose histories, with the exception of LeRoi Jones-era Amiri Baraka, have been systematically excluded.24

This is not simply a case of the neglect of work from a particular period: the Occult School beginning in the mid-fifties, Umbra in the early-to-mid sixties. The new wave of radical queer publications in the seventies, too, has suffered from decades of popular and scholarly neglect, its political charge occulted by the increased mainstreaming of queer history. In recent years, valuable work on these contexts has appeared from Emily Hobson, Nat Raha, and Julie R. Enszer, among others: it's to be hoped that more will follow. Such neglect is all the more reason to pay attention now. Against the advent of pinkwashing, homonationalism, the rolling back of women's reproductive rights, and apologias for the army and the police, the work of the Occult School continues to reach out to "the ones who ball, i.e. throw across" — intimating a past long suppressed, intimating a future we might have against the supposedly fated future.

Acknowledgments: This text relates to a broader book project, Never by Itself Alone: Queer Poetry in Boston and San Francisco, 1943-Present (Oxford University Press, forthcoming), research for which has been supported by a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Warwick. I'd like to extend heartful thanks to those who've assisted with this research: in particular, David Abel for sharing his in-progress research on Ed Marshall, Joe Torra, for discussing his research on Stephen Jonas, David Rich, for discussions of Jonas and Gerrit Lansing, Michael Bronski, for discussions of Fag Rag, and Michael Seth Stewart, Raymond Foye, and the late Kevin Killian, for discussions of Wieners, Spicer, and the Boston Newsletter.

David Grundy is the author of A Black Arts Poetry Machine: Amiri Baraka and the Umbra Poets (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019) and Never by Itself Alone: Queer Poetry in Boston and San Francisco, 1943-Present (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) and coeditor, with Lauri Scheyer, of Selected Poems of Calvin C. Hernton (Wesleyan University Press, 2023). He is currently a British Academy Fellow at the University of Warwick.

References

- Gerrit Lansing, "The Preface to the Reader," in Stephen Jonas, Exercises for Ear (London: Ferry Press 1968), 6.[⤒]

- For discussions of biographical details relating to Stephen Jonas, I am particularly grateful to David Rich and Joe Torra. See also Jospeh Torra, "Introduction" and Rich, "Postcript" in Stephen Jonas, Arcana: A Stephen Jonas Reader, edited by Garrett Caples, Derek Fenner, David Rich, and Joseph Torra (San Francisco: City Lights, 2019), 17-27 and 249-260.[⤒]

- Jonas to Marshall, July, 31, 1957. Many thanks to David Abel for providing transcriptions of the Jonas-Marshall correspondence, originals of which can be found in the Jack Spicer papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.[⤒]

- Jonas to Marshall, Feb 1957. [⤒]

- Quoted in George Butterick, "Edward Marshall," Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 16. The Beats: Literary Bohemians in Postwar America, Part 2: M-Z (Detroit: Gale Research, 1983), 372.[⤒]

- "Swished," from Robert Dewhurst, "John Wieners: A Career Biography, 1954-1975," Part 1 of Ungrateful City: The Collected Poems of John Wieners. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation (Graduate School, University of Buffalo, State University of New York, 2014), 22-23.[⤒]

- "No violence of the mind": Jack Spicer, "Jack Spicer's Letters to Allen Joyce," Sulfur 10 (1984): 140-153.[⤒]

- John Wieners, "Chop-House Memories," Cultural Affairs in Boston: Poetry & Prose, 1956-1985, edited by Raymond Foye (Santa Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1988), 80.[⤒]

- Wieners, "Chop-House Memories."[⤒]

- Jack Spicer, "Notebook 4, 1956." Box 8, Folder 4, Series 2:2. Books, Collected and Serial Poems 1948-1966 [1975], Jack Spicer Papers, BANC MSS 2004/209, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Poem published in Be Brave to Things: The Uncollected Poetry and Plays of Jack Spicer, edited by Daniel Katz (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2021), 98.[⤒]

- Charley Shively, "Stephen Jonas," Fag Rag No. 9 / Gay Sunshine No. 22: Stonewall 5th Anniversary Issue (Summer 1974), 19.[⤒]

- Wieners to Charles Olson, January 8, 1957, Yours Presently: The Selected Letters of John Wieners, edited by Michael Seth Stewart (Albuquerque, NM: University of Mexico Press, 2020), 43[⤒]

- Robert Duncan. "Letter (1st of a Series)," Measure II (1958), 63.[⤒]

- Grateful thanks to David Abel for sharing his biographical research of Ed Marshall.[⤒]

- Jonas to Marshall, Wed. ? 1957.[⤒]

- Ed Marshall, "Memory as Memorial in the Last," Yugen 8 (1962), 57.[⤒]

- David Abel, "Edward H. Marshall (1932-2005)," The Text Garage (May 22, 2013). Access via: https://web.archive.org/web/20130707134228/http://thetextgarage.com/2013/05/edward-marshall/.[⤒]

- "Talking about 'the brotherhood of man'": from an undated scrap in Lansing's papers. I am indebted to David Rich for providing this quotation.[⤒]

- Gerrit Lansing, "The Burden of SET # 2 (editorial)," SET 2 (Winter, 1963-1964), 42.[⤒]

- John Wieners, "As Preface to Transmutations," in Cultural Affairs in Boston: Poetry & Prose, 1956-1985, ed. Raymond Foye (Santa Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 2988), 32.[⤒]

- Wieners to Duncan McNaughton, November 7, 1969. In "For the Voices": The Letters of John Wieners, edited by Michael Seth Stewart (CUNY Academic Works, 2014), 468. Access via: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/292.[⤒]

- Dewhurst, Ungrateful City, 47.[⤒]

- Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980: A Sourcebook of Information (New York: New York Public Library and Granary Books, 1998), 15.[⤒]

- "Ishmael Reed on the Miltonian Origin of the Other," Blowing Minds; 1965-1972 The East Village Other: The Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press. ("Site created by the NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute in conjunction with its NYTimes.com community news and information site, The Local East Village.")Access via: https://nyujournalismprojects.org/eastvillageother/recollections/reed.[⤒]